Return of the Large and Super Regional Buyers?

It is sort of like the pre-crisis days, but not really. Bank acquisition activity involving non-assisted transactions has been gradually building since the financial crisis. The only notable interruption occurred in the second half of 2011 when the downgrade of the U.S. by S&P (but not Moody’s or Fitch) and a funding crisis among many European banks caused markets to fall sharply.

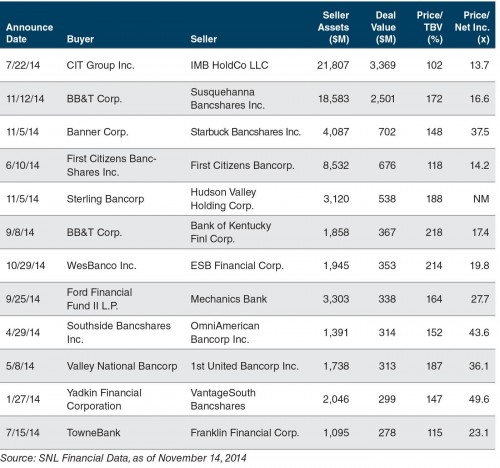

As of November 14, 260 bank and thrift acquisitions had been announced this year according to SNL Financial, which compares to 246 deals for all of 2013. Pricing continues to gradually improve too. The year-to-date average P/TBV is 135% compared to 120% in 2013 and 116% in 2012. In a sense, a declining median P/E points to higher valuations because sellers as a group are posting better profitability than several years ago. The median P/E ratio this year is about 28x compared to 23x in 2013 and 34x in 2012. Figures 1 and 2 highlight some of these comparisons for deals both in 2014 and from 2009-2013. Although it will be a subject for a later post in Bank Watch, we believe most buyers are paying roughly 10-13x the buyer’s normalized earnings with after-tax cost saves and normalized credit costs.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The heyday of M&A activity for investors was the 1990s when over 500 bank and thrift deals were announced in 1994 and 1998. Deal activity peaked last decade at 323 in 2007. Not coincidentally, cycle peaks in public market bank valuations occurred near the peaks in M&A activity in 1998 and 2007. When viewed as a percent of banks at the beginning of each year, deal activity has been relatively steady with 3-4% of banks being absorbed through acquisition, with the exception of 2008, 2009 and 2011.

One notable aspect of the bank M&A market since the financial crisis has been the absence of larger acquirers other than periodic deals. The primary reason cited has been regulatory challenges as large banks implement tough compliance requirements as part of Dodd-Frank and other regulatory mandates that emerged from the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Also, many bankers and corporate securities attorneys have publicly commented (and to us) that the Fed does not want to see merger applications from the largest banks; rather, they want consolidation to occur from the bottom rather than the top of the industry.

M&T Bank Corporation (MTB) remains the poster-child for the industry in terms of what can go awry with a merger application when a compliance issue emerges. M&T announced a deal to acquire then $44 billion asset Hudson City Bancorp on August 27, 2012 for $3.8 billion as shown in Figure 2. Over two years later the deal remains pending due to compliance issues that emerged for M&T, including some issues related to its 2011 acquisition of Wilmington Trust Corporation. Although on a smaller scale, BancorpSouth (BXS) recently extended by about a year the date of two definitive agreements it had entered into to acquire community banks in Louisiana and Texas due to compliance issues that emerged after the definitive agreements were signed.

CEO Richard Davis of US Bancorp (USB) has opined that acquisitions by larger banks will be episodic and focused like USB’s acquisition of Citizen Financial Group’s Chicago franchise earlier this year rather a broad-based trend. Nevertheless, the return of BB&T Corporation (BBT) to the acquisition market this year may signal larger banks are becoming more comfortable with their regulatory standing to resume acquisitions. In late 2013 BB&T announced a deal to acquire 22 Texas offices from Citigroup Inc. (C); it then announced a second purchase for 41 Texas branches in September. Within a week BB&T announced a $367 million deal for Bank of Kentucky Financial Corporation (BFKY). In November, it announced a $2.5 billion acquisition of Pennsylvania-based Susquehanna Bancshares (SUSQ). See Figure 1 for other details of these transactions.

The largest transaction announced year-to-date is CIT Group’s (CIT) $3.4 billion deal for IMB HoldCo, a privately-held entity that formed OneWest Bank from the failed IndyMac Bank, as shown in Figure 1. The transaction may be an outlier because CIT was under pressure from the Federal Reserve to build a core deposit franchise that does not yet exist in subsidiary CIT Bank, which traces its roots to a Utah industrial loan charter.

We do not know whether Davis is right about large bank M&A activity being episodic rather than on the cusp of picking-up. What is apparent is that the operating environment for banks remains challenging with pressure on NIMs, increasing regulatory costs and limited opportunities to improve fee income. As a result, we see no reason deal activity will slow from the 3-4% of the industry being absorbed each year other than as a result of a sharp drop in markets and/or a downturn in credit. The return of BB&T and the addition of the likes of First Horizon National Corporation (FHN) should, at the margin, support activity and maybe pricing to the extent it supports investor and banker confidence in the sector.

Reprinted from Bank Watch, November 2014.