An Overview of Saltwater Disposal

Part 2 | Economics of the Industry

In a prior blog post, we provided an overview of the saltwater disposal (SWD) industry, detailing the source of demand for SWD services, the impact of the shale boom, geographic distribution, site selection, construction, and regulation. We now take a look at the economics of the SWD industry and the trends that impact the economics.

SWD Economics

In the past, SWD wells were typically drilled and operated by producers for the purpose of handling the producers’ own disposal needs. However, the growing inefficiency of individual operators having in-sourced SWD operations has in recent years created an increased demand for specialized outsourced SWD services. The expertise and economies of scale provided by these independent SWD service providers allow for reductions in the saltwater transportation and disposal expense to the producer. As a result, the operation of SWD facilities as a stand-alone business has shown enormous growth in recent years.

Revenue Streams

Revenues streams to SWD operators consist primarily of disposal fees – typically in the range of $0.50 to $2.50 per barrel – and skim oil sales. Produced water contains significant amounts of suspended crude oil that the SWD facility “skims-off” (by various methods) and sells to increase revenues. Where disposal services are abundant, the cost is typically in the lower third of the indicated range. Locations with fewer available SWD facilities can see fees in the upper end of the range. Skim oil volumes are typically quite small relative the volume of produced water received for disposal. However, the sale of the skimmed oil can account for 10% to 30% of total SWD revenues. The portion of revenues attributable to skim oil sales depends on the SWD facility’s skimming and impurity removal capabilities, in addition to the presence of a local market for alternative skim oil use.

Revenues streams to SWD operators consist primarily of disposal fees – typically in the range of $0.50 to $2.50 per barrel – and skim oil sales.

Additional revenues may be generated by providing trucking services for the purpose of transporting the produced water from the well site to the disposal facility. Revenues from such services can vary widely. Transport rates are typically near $1 per barrel per hour of transport time. Where SWD facilities are readily available and the distance from the well site is minimal, the trucking cost may only add $0.50 per barrel. However, the incremental revenue can reach $4 to $6 per barrel where facilities are lacking and the distance is significant.

As with the in-sourcing of SWD operations by producers, the provision of trucking services by SWD facility operators is on the decline. As the oilfield waste disposal industry has rapidly grown in recent years, the ability to provide specialized services at significant economies of scale has led to oilfield waste transportation services being provided as a stand-alone business. As detailed below, the growing benefits of transporting produced water to SWDs via pipeline has also contributed to the decline in trucking services among SWD facility operators.

Cost Structure

The structure of a SWD facility’s expenses is significantly skewed to fixed costs relative to variable costs. Like other fixed asset-intensive businesses, a large portion of a SWD facility operator’s costs are incurred up-front in the construction of the facility, including the cost of drilling the primary disposal well and any back-up well. While drilling costs can vary markedly based on the site geology, the target zone, and well depth, the total facility cost can easily reach $3 million to $4 million even if the facility offers no produced water transportation via pipeline.

Ongoing expenses are fairly limited and are primarily comprised of power and maintenance/repair costs. Incremental costs are typically quite low, often less than $1 per barrel. Labor costs vary little whether disposal volumes are high or low. Ticketing and invoicing processes are typically heavily automated, and therefore, related expenses do not vary significantly with volumes.

The one area of expense that is to some degree within the control of the SWD operator is maintenance expenses. The SWD operator is well advised to exercise diligence in the maintenance of the SWD well as any downtime, expected or unexpected, can be costly in terms of lost revenues.

Focus on Volume

Given the fixed-heavy cost structure, the SWD facility operator’s primary lever for improving operating results lies in increasing volumes. However, for the well operator, the primary consideration in choosing a SWD facility is the transportation cost, which is largely a factor of the distance from the well site to the disposal facility. So, once the SWD facility is sited, the primary SWD decision driver – distance – is fixed and can’t be altered. To gain more disposal business, SWD facilities often provide transport services via truck. However, as previously indicated, recent trends have moved SWD facility operators away from trucking services.

Trends in Volume Acquisition

Historically, the transportation of produced water to a commercial disposal facility has been heavily weighted toward trucking. Due to the smaller volumes of water requiring disposal and the typical patchwork of acreage controlled by any single E&P company, the construction and use of pipeline systems for gathering and transporting produced water to a central disposal facility was cost-prohibitive. However, with the vast increase in produced water volumes in recent years, and the recent trend among the E&Ps to aggregate more contiguous acreage, the feasibility of pipeline systems has grown. With trucking costs now more than doubling pipeline transportation costs in many markets, the large up-front cost of constructing a pipeline network is often no longer an economic hindrance.

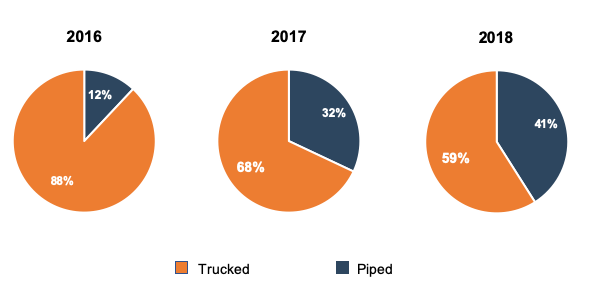

Similarly, several producers have put in place longer-term programs for the systematic development of their large – and more contiguous – acreage holdings. As part of these programs, the producers have found it economically viable to build out pipeline systems for gathering and transporting produced water to local SWD networks. Although the trucking of produced water is still dominant in some areas – the Bakken and the Eagle Ford – SWD operators in the Delaware Basin have indicated that piped volumes are likely exceeding trucked volumes in that pipe-heavy area. Data from NGL Energy shows the progression of piped versus trucked produced water in recent years.

While many of the more extensive pipeline systems were originally operated by the E&Ps, much of the current systems are held by businesses that specialize in oilfield waste disposal via E&P asset drop-down and asset sale transactions.

Produced Water Contracts

Along with the rise in the prevalence of produced water pipeline gathering and transport systems has come the need for the owners/operators of those systems to ensure the disposal volumes into their systems will be sufficient to service the debt taken on related to the pipeline construction or acquisition. In pursuit of steadily produced water volumes, SWD operators and E&Ps have begun entering into contractual commitments that often include dedicated acreage and/or take-or-pay volumes. These contractual relationships are often multi-year agreements, ensuring a steady stream of produced water. The enhanced economies of scale result in a risk/return profile that is less like that of oilfield service providers and more like midstream companies. This lowers the cost of capital for SWD operators.

Produced Water Recycling

One detrimental economic trend in the SWD industry is produced water recycling.

One detrimental economic trend in the SWD industry is produced water recycling. Hydraulic fracturing requires enormous amounts of water and therefore results in enormous amounts of produced water. Traditionally, fracking operations only utilized freshwater. However, in recent years operators have begun experimenting with mixes of fresh and produced water for fracking purposes with largely favorable results. This brings the potential for significant quantities of produced water no longer heading to SWD facilities for disposal but instead being recycled and reused at the well site. While reducing both freshwater supply and produced water disposal expenses would seem to be an obvious benefit to the operator, produced water recycling carries its own cost.

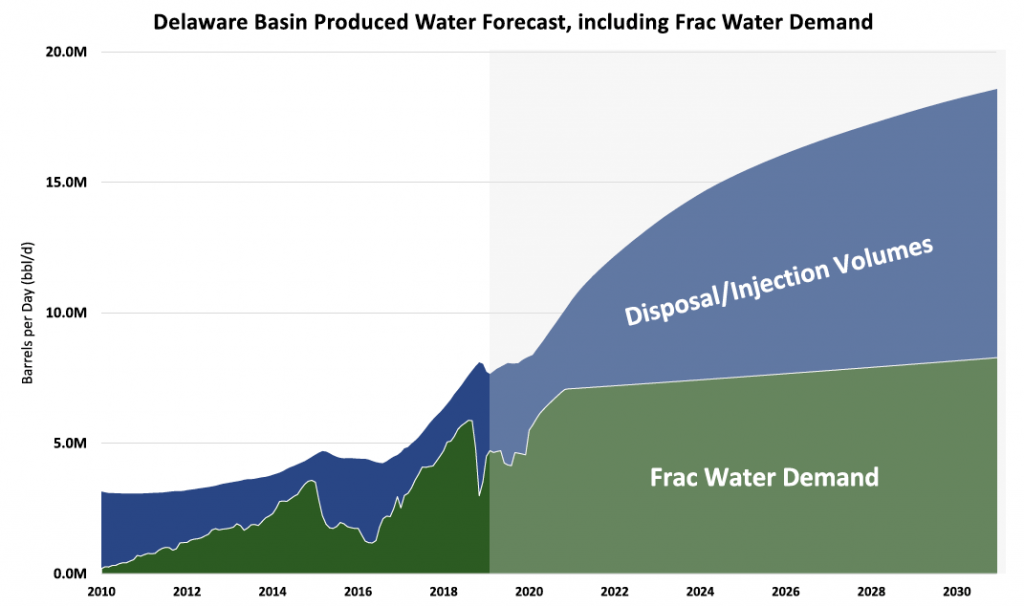

Produced water recycling entails a multiple-step process with each step removing a certain part of the produced water mix. Although the recycling process does not have to bring the produced water to a “drinking water” level of freshness, recycling to the level required for use in fracking can entail a significant expense. The recycling economics often hinges on the availability – and therefore cost – of freshwater for fracking use. In areas where freshwater is abundant and inexpensive, recycling economics are less beneficial. In areas where freshwater is scarce and expensive, recycling often makes economic sense. As recycling technology improves and greater efficiencies are realized, it’s likely that a greater percentage of produced water will be reused, rather than removed for disposal. However, research by Raymond James indicates that fracking-related water demand growth falls far short of estimates of produced water disposal demand growth, even with produced water recycling considerations.

As of now, recycling of produced water is still in early development with estimates of disposal to recycle ratios at 20:1.

Summary

As detailed, the outlook of the SWD industry is quite favorable although the economics are, and will continue to be, in a state of flux as the industry grows and matures. Despite some potential detrimental market dynamics along the way, the overall direction points to strong benefits to investors as the business of SWD continues to evolve away from a being cost center for operators, to a cash flow generating third-party service provider to operators.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights