The following is an installment in our series “What Keeps Family Business Owners Awake at Night”

Consider the following perspectives on diversification and risk:

“Diversification is an established tenet of conservative investment.” – Legendary value investor Benjamin Graham

“Diversification may preserve wealth, but concentration builds wealth.” – Legendary value investor Warren Buffett

The appropriate role of diversification in multi-generation family businesses is not always obvious. One of the most surprising attributes of many successful multi-generation family businesses is just how little the current business activities resemble those of 20, 30, or 40 years ago. In some cases, this is the product of natural evolution in the company’s target market or responses to changes in customer demand; in other cases, however, the changes represent deliberate attempts to diversify away from the legacy business.

What is Diversification?

Diversification is simply investing in multiple assets as a means of reducing risk. If one asset in the portfolio takes a big hit, it is likely that some other segment of the portfolio will perform well at the same time, thereby blunting the negative impact on the overall portfolio. The essence of diversification is (lack of) correlation, or co-movement in returns. Investing in multiple assets yields diversification benefits only if the assets behave differently. If the correlation between the assets is high, the diversification benefits will be negligible, while adding assets with low correlations results in a greater level of risk reduction.

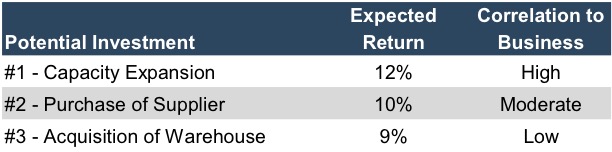

To illustrate, consider a family business deciding which of the following three investments to make:

There is no unambiguously correct choice for which investment to make. While the capacity expansion project offers the highest expected return, the close correlation of the returns to the existing business indicates that the project will not reduce the risk – or variability of returns – of the company. At the other extreme, the warehouse acquisition has the lowest expected return, but because the returns on the warehouse are essentially uncorrelated to the existing business, the warehouse acquisition reduces the overall risk profile of the business. The correct choice, in this case, should be made with respect to the risk tolerances of the shareholders and how the investments fit the strategy of the business.

Diversification to Whom?

Business education is no less susceptible to the lure of fads and groupthink than any roving pack of middle schoolers. When I was being indoctrinated in the mid-90s, the catchphrase of the moment was “core competency.” If you stared at any organization long enough – or so the theory seemed to go – you were likely to find that it truly excelled at only a few things. Success was assured by focusing exclusively on these “core competencies” and outsourcing anything and everything else to someone who had a – you guessed it – “core competency” in those activities. Conglomerates were out and spin-offs were in. With every organization executing on only their core competencies, world peace and harmony would ensue. Or something like that.

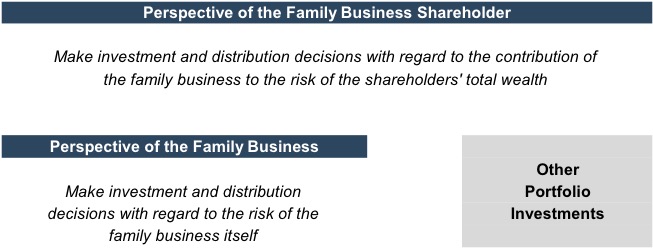

I don’t know what the status of “core competency” is in business schools today, but it does raise an interesting question for family businesses: whose perspective is most important in thinking about diversification? If the relevant perspective is that of the family business itself, the investment and distribution decisions will be made with a view to managing the absolute risk of the family business. If instead the relevant perspective is that of the shareholders, investment and distribution decisions are properly made with a view to how the family business contributes to the risk of the shareholders’ total wealth (family business plus other assets).

Modern finance theory suggests that for public companies, the shareholder perspective should be what is relevant. Shareholders construct portfolios, and presumably the core competency of risk management resides with them. Corporate managers should therefore not attempt to diversify, because shareholders can do so more efficiently and inexpensively. In other words, corporate managers should stick to their core competencies and not worry about diversification.

That’s all well and good for public companies, but for family businesses, the most critical underlying assumptions – ready liquidity and absolute shareholder freedom in constructing one’s portfolio – simply does not hold. Family business shares are illiquid and often constitute a large proportion of the shareholders’ total wealth. Further, as families mature, shareholder perspectives will inevitably diverge.

For example, consider two cousins: Sam has devoted his career to managing a non-profit clinic for the underprivileged, and Dave has enjoyed an illustrious career with a white-shoe law firm. Both are 50 years old and both own 5% of the family business. Sam’s 5% ownership interest accounts for a significantly larger proportion of his total wealth than does Dave’s corresponding 5% ownership interest. As a result, they are likely to have very different perspectives on the role and value of diversification for the family business. Sam will be much more concerned with the absolute risk of the business, whereas Dave will be more interested in how the business contributes to the risk of his overall portfolio.

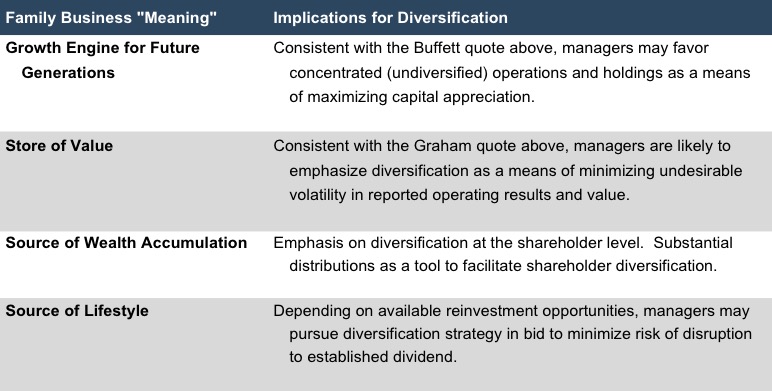

We wrote in a previous post about the four basic “meanings” that a family business can have. What the business “means” to the family has significant implications for not only distribution and reinvestment policy, but also the role of diversification in the business.

So how should family businesses think about diversification? When evaluating potential uses of capital, family business managers and directors should consider not just the expected return, but also the degree to which that return is correlated to the existing operations of the business. Depending on what the business “means” to the family, the potential for diversification benefits may take priority over absolute return. There are no right or wrong answers when it comes to risk tolerance, but there are tradeoffs that need to be acknowledged and communicated plainly. Family shareholders deserve to know not just the “what” but also the “why” for significant investment decisions.