What Is a “Level” of Value, and Why Does it Matter? (Part 2)

In last week’s post, we defined the three principal levels of value and explained that the levels reflect differing perspectives on expected future cash flows and risk. This week, we turn our attention to the importance of the levels of value for family businesses.

One of the great strengths of a family business is the ability to take the long view. Unburdened by the quarterly reporting cycles of publicly traded companies, family businesses can make investing and operating decisions for long-term benefit without worrying about the effect on next quarter’s earnings. One of the foundations of this long-term perspective is the stability of ownership within the family.

With an indefinite holding period, why does the value of the family business even matter? While the family may have an indefinite holding period, the fact of mortality means that individual shareholders do not. So, even for committed families, transactions will occur, and valuation will matter. In our next two posts, we consider four potential transactions in which getting the level of value right matters a lot.

Estate Planning

Many family shareholders will determine that it is advantageous to transfer wealth to heirs while still living. Regardless of the specific technique used, the value of shares in the family business is a cornerstone of estate planning. Under the IRS’ definition of fair market value, the appropriate level of value depends on the attribute of the block of shares being transferred. Since estate planning almost always involves transactions of minority interests in the family business, the nonmarketable minority interest level of value is relevant.

Measuring the value of shares in the family business at the nonmarketable minority interest level of value is a two-step process. First, we consider what the shares would be worth if they were traded on an exchange (i.e., the marketable minority level of value). Second, we determine an appropriate discount to apply to that value to reflect the unfortunate side effects of owning a minority interest in a private company. The magnitude of that discount depends on factors like the expected duration of the holding period until a liquidity event, the level of interim distributions, and the expected pace of capital appreciation. When combined with an assessment of the risks facing the investor, these factors determine the marketability discount, which, in turn, defines the fair market value of the shares on a nonmarketable minority interest basis.

Corporate Development

Family businesses have two basic pathways for growth: organic growth through capital expenditures (“build”) or non-organic growth through acquisitions (“buy”). The pathways are not mutually exclusive. Some families are culturally averse to acquisitions, while for others a disciplined acquisition strategy is part of the family’s business DNA.

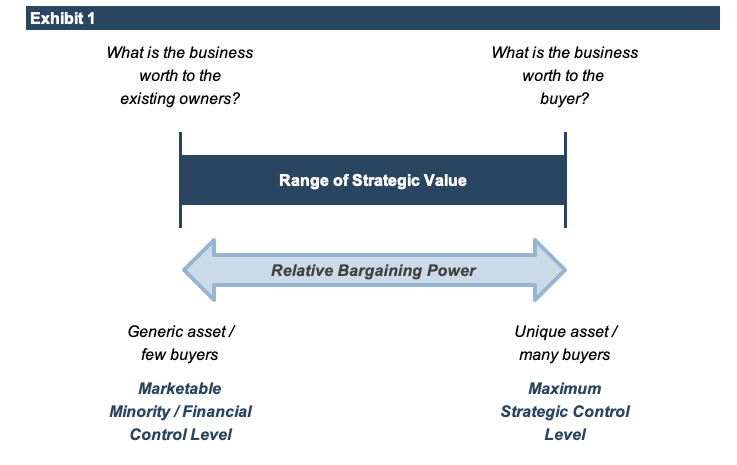

For family business acquirers, developing an appropriate valuation of the target is essential. As one of our colleagues is fond of saying: “Bought right, half right.” Regardless of the strategic merits of a proposed acquisition, overpayment will weigh on the returns available to future generations of the family. When formulating a bid price for a potential target, acquirers should seek to answer two questions.

- What is the business worth to the existing owners? Selling their business to you means that the existing owners will be giving up the future cash flows they expect the business to generate under their stewardship. This reflects the financial control level of value, which as we noted in last week’s post, is probably not much different from the marketable minority value.

- What is the business worth to us? To answer this question, acquirers need to carefully evaluate how the target “fits” with their existing business. Will the combination of the two businesses generate revenue synergies (i.e., 2 + 2 = 5)? Or are there duplicative costs that can be eliminated as a means of generating higher margins for the combined entity? Perhaps the combination will reduce the risk of the family business, or perhaps the family has access to lower cost capital than the existing owners. In any event, family business acquirers should develop forecasts for the pro forma combined entity using well-supported inputs that reflect the strategic case for the acquisition to determine what the business is worth to them.

The difference between these two values defines the “space” over which negotiations will center. The ultimate purchase price will reflect the relative bargaining power of the two parties. As illustrated in Exhibit 1, bargaining power is a function of the number of likely buyers for the target, and whether the target represents a generic or unique opportunity for buyers.

To avoid overpaying, savvy family business acquirers focus not just on what the target could be worth to them, but also what the target is worth to its current owners, along with a careful assessment of the factors that influence the relative bargaining power of the parties.

Divestitures

At some point, many families transition to being enterprising families. In other words, they are defined by the fact that they pursue economic opportunities together, rather than by continued ownership of the legacy family business. In pursuit of broader portfolio management objectives, enterprising families may sell businesses from time to time. In this case, the dynamics described in the preceding section are reversed.

- As the seller, you won’t have direct access to what your business could be worth to the buyer. However, knowing how your industry is structured and how your business operates, you should be able to estimate potential revenue synergies and cost saving opportunities available to the buyer.

- In order to achieve a sales price closer to the value of your business to the buyer, it is important to identify the attributes of your business that differentiate it from other potential acquisition targets available to buyers. Further, generating interest from a larger pool of buyers is essential to reaping greater proceeds from a divestiture.

Conclusion

In this week’s post, we have demonstrated how critical getting the level of value right is for family businesses for estate planning, acquisitions, and divestitures. Next week, we will look at the levels of value in the context of shareholder redemption transactions. If you could benefit from an outside perspective on a pending transaction for your family business, give one of our experienced valuation professionals a call.

See Part 1 of this series here.

See Part 3 of this series here.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director