Aggregators Continue to Attract Equity Capital

In previous posts, we have delineated between royalty trusts and mineral aggregators and discussed the valuation implications of prevailing high dividend yields of public royalty trusts. Yields remain elevated, and these trusts have declined in their usefulness from a valuation benchmarking perspective. In this post, we focus on mineral aggregators. We also offer insights on the investment landscape at large and particularly as it relates to the minerals subspace by providing an update on the most recent IPO, Brigham Minerals (MNRL).

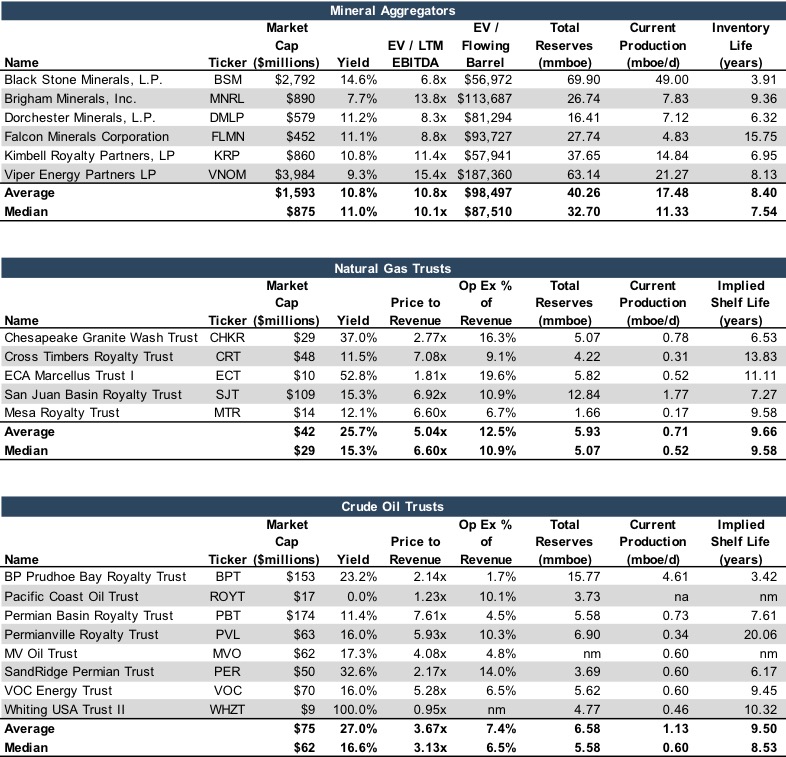

Market Data for Aggregators and Trusts

The following tables provide some critical market data for valuation purposes.

Since our last update, SandRidge Mississippian Trusts I and II (SDT and SDR, respectively) were delisted in mid-November as the stocks fell below $1.00 in May and traded below that mark for six months. All else equal, public royalty trusts are expected to decline in value as investors get their return almost exclusively from yields because production declines over time. Thus, trusts eventually being delisted is not a surprising outcome due to restrictions on acquiring additional acreage or wells. Given the eponymous operator SandRidge Energy’s struggles, it’s even less surprising these two trusts were delisted. SandRidge Permian Trust has avoided this fate for the time being, due in part to its attachment to the prolific Permian and sale to Avalon Energy, but the trust has also been put on notice.

Unlike public royalty trusts, mineral aggregators are not restricted from acquiring additional interests, which makes them more of a going concern by comparison. This is among many reasons investors have increasingly turned towards mineral aggregators. Long-time readers of the public mineral interest portion of our blog will note the revamped look at value drivers and key benchmarks for mineral aggregators.

Public Markets Unreceptive of Energy Sector

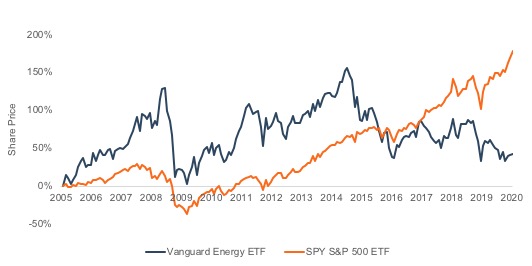

The stock market has been booming over the past decade as the economy has ridden the longest expansion in history. Investors in the energy sector, however, have not experienced the same joyful ride. In 1990, energy made up 15% of the S&P 500 sector weightings, but in 2019, that figure was down to 5%. Ironically, over the same period, the United States’ oil and gas production surpassed all countries and claimed the top of the leaderboard, becoming the world’s largest producer. Depressed commodity prices have also likely aided valuations for companies in other sectors as transportation costs are lower in an increasingly globalized economy with two-day shipping becoming common place.

The graph below shows the relationship between the Vanguard Energy ETF, created in 2004, and the SPY Index over a 15-year period. Slow economic growth coming out of the recession caused Energy to outperform, but commodity price declines in late 2014 began a reversal that has widened since 2017.

Energy vs. S&P 500

There are many reasons that this story has unfolded such as diminishing return on investment, fluctuation in commodity prices, and oversupply, but we do not dive into that in this post. Instead, we want to illustrate the ways in which mineral aggregators have been able to manage some of these issues.

Mineral aggregators are constructed to diversify capital among many superior plays and specific operators. This niche in the energy market allows investors to capitalize on both current yield and capital appreciation with the aggregators’ reinvestment capabilities. Crucially, royalty holders do not bear operating and drilling costs as these costs are paid by upstream E&P companies. Brigham Minerals articulates the benefits of the business model as follows:

“There are many advantages of the mineral acquisition model, including no development capital expenditures or operating costs, no exposure to fluctuating oilfield service costs and higher margins than E&P operators without associated operational risks.”

Mineral aggregators receive a royalty based on revenue and are thus isolated from a number of field-level economic issues. This is not unlike the restaurant industry, where franchisors command a much higher valuation than the operators to whom they franchise. Declining same-store sales figures in that industry are hurting profitability for operators grappling with the necessity for capital expenditures to fund future growth while those collecting royalties off the top can prosper with their asset-light models. Sound familiar?

Brigham Minerals Seasoned Equity Offering

In a previous post, we discussed the much-anticipated Brigham Minerals’ IPO in April 2019. The upsized offering was sparked by higher than expected demand. Many saw the IPO as an investment opportunity that promoted cash flow, something that operators in the market were not providing. There was speculation that additional mineral companies would likely IPO over the course of 2019 given the demand for Brigham Minerals, but that turned out not to be the case. In December of 2019, however, Brigham Minerals announced in an S-1 a seasoned equity offering of 11 million common shares. The Company offered 6 million new shares of its common stock, and some selling shareholders sold an additional 5 million shares. Shares were priced at $18.10, likely a psychological threshold, as it was priced just ten cents above the IPO price only eight months prior.

Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, and RBC Capital Markets acted as lead booking-running managers for the offering, and they were granted a 30-day greenshoe option totaling an additional 1.65 million shares though these were not exercised as the share price remained above the issuance price, averaging $19.70 for the first month of trading.

Generally speaking, 2019 was a poor year for IPO’s with ride-share companies Uber and Lyft among the high-profile unicorns that floundered. Peloton opened 6.9% below its trading price and multiple companies, perhaps most notably WeWork, decided to scrap the IPO altogether. Brigham’s IPO success and perhaps more importantly its ability to issue additional equity just eight months later may encourage private equity firms invested in minerals companies to test the IPO market.

Conclusion

Mineral aggregators appear to have supplanted public royalty trusts as a key means for investors to get exposure to the sector while avoiding costly drilling expenses. While functionally related to drilling activity and well performance, aggregators allow investors to avoid cost burdens. As such, valuations for the aggregators behave differently than other participants in the energy sector.

We have assisted many clients with various valuation and cash flow questions regarding royalty interests. Contact Mercer Capital to discuss your needs in confidence and learn more about how we can help you succeed.

Energy Valuation Insights

Energy Valuation Insights