New York Statutory Fair Value: Matter of Giaimo

Peter A. Mahler, Esq., of Farrell Fritz, P.C., in New York, reviewed a statutory fair value case issued in New York on April 25, 2011 (via New York Business Divorce):

An epic corporate governance and stock valuation battle between rival siblings, fighting over a Manhattan real estate portfolio worth upwards of $100 million, generated an important ruling last week by New York County Supreme Court Justice Marcy S. Friedman. Justice Friedman’s decision in Matter of Giaimo (EGA Associates, Inc.), 2011 NY Slip Op 50714(U) (Sup Ct NY County Apr. 25, 2011), and the underlying, 184-page Report & Recommendation by Special Referee Louis Crespo dated June 30, 2010, are must reading for business appraisers, attorneys and owners of closely held real estate holding corporations who are involved in, or who are contemplating bringing or defending against, a ”fair value” proceeding under New York’s minority shareholder oppression or dissenting shareholder statutes.

The case involved two C corporations that collectively owned 19 residential apartment buildings, most or which are located in Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The companies are EGA Associates, Inc. (“EGA”) and First Avenue Village Corp (“FAV”).

The stock in the corporations was owned equally by three siblings, Edward, Robert and Janet. Edward’s will provided that his stock be divided equally between his surviving siblings at his death; however, Janet claimed that shortly prior to his death in 2007, Edward sold one share of each corporation to her, giving her control of both corporations at just above 50% of the shares.

Robert filed suit to invalidate the sale of the shares, and simultaneously, Robert sought judicial dissolution of the corporations (EGA and FAV). Janet elected to purchase Robert’s shares under Section 1118 of the Business Corporation Law in New York, and the matter was referred to a Special Referee to determine the fair value of the shares of the two corporations.

An 18-day trial occurred in January, February and early March of 2009. The Special Referee issued a report of more than 180 pages on June 30, 2010. Justice Friedman’s opinion was issued April 25, 2011.

Counsel for Robert Giaimo was Philip H. Kalban of Putney, Twombly, Hall & Hirson LLP, New York City. Having attended a substantial portion of the trial, it is clear to me that Robert was well-represented in this matter. I asked Phil to read this to help ensure the factual accuracy of my comments. However, I am responsible for the content in this article.

Summary of the Issues

The Special Referee first determined the market values of the various apartment buildings, siding mostly with Robert’s real estate appraiser, but making adjustments in the appreciation rates that lowered value overall. There were two important valuation issues and some related issues pertaining to Edward’s estate (and that of the siblings’ mother, as well). The two important valuation issues are:

- The applicability of a marketability discount (also called the discount for lack of marketability or DLOM). The Special Referee concluded that no marketability discount should be applied, and Justice Friedman agreed, although not for the same reasons.

- Whether, in a fair value determination in New York, it was appropriate to consider the entire built-in gain (embedded capital gains, or BIG) in each of the C corporations. The issue was significant because the book values of the two corporations were minimal in relationship to the appreciated values of the apartment buildings and a combined federal, state and New York City capital gains tax of nearly 46%.

Janet’s counsel (and business appraisal experts) argued that the entire BIG should be applied as a liability in determinations of net asset value. Robert’s counsel argued that none of the BIG should be considered as a liability, but his business appraisal expert testified as to appropriate methods for partial consideration if the court determined that a BIG deduction was appropriate.

The court agreed with the special referee’s application of a so-called “Murphy Discount,” which was decided while the Special Referee was preparing his report (Matter of Murphy (United States Dredging Corp.), 74 AD3d 815 (2d Dept 2010)). The concluded BIG liability was about 50% of the combined embedded gains in the two corporations.

I know what Robert’s expert concluded, because I was that expert.

No Marketability Discount

No minority interest discount was applied in Giaimo, and no marketability discount was applied, either. The Mahler blog post summarizes the marketability discount issue:

As to DLOM, Justice Friedman states her disagreement with Mercer’s position, upon which Referee Crespo relied, that the valuation of a business as a going concern at a financial control level of value is inconsistent with a marketability discount. Justice Friedman finds Mercer’s position contrary to applicable precedent, particularly the Court of Appeals’ 1995 Beway decision (Matter of Friedman [Beway Realty Corp.], 87 NY2d 161) likewise involving a real estate holding company in which the court expressly upheld application of DLOM in fair value proceedings. Justice Friedman rejects Referee Crespo’s effort in his Report to distinguish Beway on the ground that, unlike in Giaimo, the properties held by the subject realty company in that case had mortgage financing.

Justice Friedman nonetheless finds that Referee Crespo’s decision not to apply a DLOM “is appropriate on this record.” Noting that fair value is a question of fact for which there is no single formula for mechanical application, she essentially finds that the subject corporations’ shares are readily marketable, stating as follows:

As discussed more fully below, in determining the built-in gains tax issue, the Referee specifically made a finding of fact, which is amply supported by the record, that the availability of similar properties on the open market is limited and that a buyer would accordingly buy the properties that EGA and FAV own through the corporations. This finding of the marketability of the corporations’ shares is as relevant to the determination as to whether to apply a discount for lack of marketability as it is to whether to reduce the value of the corporations by embedded taxes. The court accordingly holds that the Referee’s award on the DLOM should be confirmed.

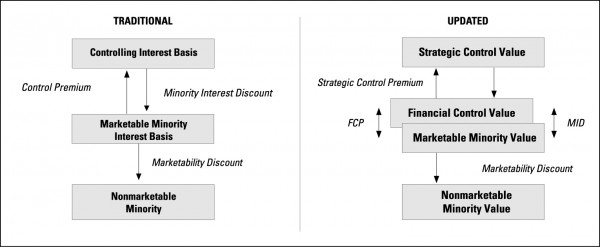

This was an excellent result for Robert as the shareholder being forced to sell his shares. The decision affirms that no marketability discount should be applied, but for reasons other than stated initially by me. I stated that the valuation of a business as a going concern at the financial control level of value is inconsistent with the application of a marketability discount. At trial, I discussed this issue at some length and supported that testimony with the now familiar levels of value chart and references to articles and texts. The levels of value chart is placed below for reference.

Visually, the application of a marketability discount lowers the conceptual level of value from marketable minority (left) or financial control/marketable minority (right) to the nonmarketable minority level of value. This is clearly a minority interest level of value and does not represent a proportionate share of the value of an entire business as a going concern.

We know that the court did not apply a marketability discount as in Beway. The rationale was also provided by Mercer based on two factors:

- I testified that the market for apartment dwellings in Manhattan was very hot. This testimony was based on detailed conversations with well-known real estate appraisers and brokers in Manhattan (which information can ordinarily be relied upon by an expert). One of Janet’s experts introduced a publication (that I had not found), which, we argued, confirmed this market condition with specific sales statistics.

- I also testified that both real estate appraisers had considered “exposure to market” in their market value determinations of the properties. Both appraisers assumed that the individual properties had been exposed to the market for periods of six to twelve months prior to the valuation dates, and that their opinions of market value reflected this exposure to market. Given that exposure to market was considered in the underlying asset appraisals, it made no economic sense to assume that the sale of the “corporate wrappers” inclusive of the properties would require additional exposure to market.

In other words, I testified, first, that there was no reason to apply a marketability discount in a going concern appraisal at the financial control level. However, the additional arguments regarding the state of the Manhattan real estate market and exposure to market only further supported the first position, which Justice Friedman did not accept. She did accept the real estate market and exposure to market arguments. Perhaps she took this position because it was not necessary for her to tackle the precedent issue in Beway directly.

The result in Giaimo was clearly a determination of fair value at the financial control level of value, with no minority interest and no marketability discounts applied. This was a good result from an economic viewpoint if fair value is to be considered to be the value of a corporation at the financial control level of value.

However, the marketability discount issue from Beway still lives on to rise up another day.

No Minority Discount in New York

Mercer did not simply disagree with the Beway decision (Matter of Friedman [Beway Realty Corp.], 87 NY2d 161). Beway states, in part (emphasis added):

A minority discount would necessarily deprive minority shareholders of their proportionate interest in a going concern, as guaranteed by our decisions previously discussed.

and,

Likewise, imposing a minority discount on the compensation payable to dissenting stockholders for their shares in a proceeding under Business Corporation Law Section 623 or 1118 would result in minority shares being valued below that of majority shares, thus violating our mandate of equal treatment of all shares of the same class in minority stockholder buyouts.

This guidance, as I read it from a valuation perspective, suggests that control shares of the same class as those minority shares being purchased pursuant to Section 1118 or 623 should be treated the same as the minority shares. This provides affirmation that the value called for in Beway is a controlling interest indication of fair value. The guidance of Beway couldn’t be clearer at this point. But to drive home the point, read the following series of paragraphs [bold emphasis added, italics in text of decision]:

Thus, we apply to stock fair value determinations under section 623 the principle we enunciated for such determinations under section 1118 that, in fixing fair value, courts should determine the minority shareholder’s proportionate interest in the going concern value of the corporation as a whole, that is, “`what a willing purchaser, in an arm’s length transaction, would offer for the corporation as an operating business’” (Matter of Pace Photographers [Rosen], 71 NY2d at 748, supra, quoting Matter of Blake v Blake Agency, 107 AD2d at 146, supra [emphasis added]).

Consistent with that approach, we have approved a methodology for fixing the fair value of minority shares in a close corporation under which the investment value of the entire enterprise was ascertained through a capitalization of earnings (taking into account the unmarketability of the corporate stock) and then fair value was calculated on the basis of the petitioners’ proportionate share of all outstanding corporate stock (Matter of Seagroatt Floral Co., 78 NY2d at 442, 446, supra).

Imposing a discount for the minority status of the dissenting shares here, as argued by the corporations, would in our view conflict with two central equitable principles of corporate governance we have developed for fair value adjudications of minority shareholder interests under Business Corporation Law §§ 623 and 1118. A minority discount would necessarily deprive minority shareholders of their proportionate interest in a going concern, as guaranteed by our decisions previously discussed. Likewise, imposing a minority discount on the compensation payable to dissenting stockholders for their shares in a proceeding under Business Corporation Law §§ 623 or 1118 would result in minority shares being valued below that of majority shares, thus violating our mandate of equal treatment of all shares of the same class in minority stockholder buyouts.

A minority discount on the value of dissenters’ shares would also significantly undermine one of the major policies behind the appraisal legislation embodied now in Business Corporation Law § 623, the remedial goal of the statute to “protect minority shareholders ‘from being forced to sell at unfair values imposed by those dominating the corporation while allowing the majority to proceed with its desired [corporate action]’” (Matter of Cawley v SCM Corp., 72 NY2d at 471, supra, quoting Alpert v 28 William St. Corp., 61 N.Y.2d 557, 567-568). This protective purpose of the statute prevents the shifting of proportionate economic value of the corporation as a going concern from minority to majority stockholders. As stated by the Delaware Supreme Court, “to fail to accord to a minority shareholder the full proportionate value of his [or her] shares imposes a penalty for lack of control, and unfairly enriches the majority stockholders who may reap a windfall from the appraisal process by cashing out a dissenting shareholder” (Cavalier Oil Corp. v Harnett, 564 A2d 137, 1145 [Del]).

Furthermore, a mandatory reduction in the fair value of minority shares to reflect their owners’ lack of power in the administration of the corporation will inevitably encourage oppressive majority conduct, thereby further driving down the compensation necessary to pay for the value of minority shares. “Thus, the greater the misconduct by the majority, the less they need to pay for the minority’s shares” (Murdock, The Evolution of Effective Remedies for Minority Shareholders and Its Impact Upon Evaluation of Minority Shares, 65 Notre Dame L Rev 425, 487).

We also note that a minority discount has been rejected in a substantial majority of other jurisdictions. ”Thus, statistically, minority discounts are almost uniformly viewed with disfavor by State courts” (id., at 481). The imposition of a minority discount in derogation of minority stockholder appraisal remedies has been rejected as well by the American Law Institute in its Principles of Corporate Governance (see, 2 ALI, Principles of Corporate Governance § 7.22, at 314-315; comment e to § 7.22, at 324 [1994]).

It should be clear that New York statutory guidance is clear in not applying a minority interest discount. However, there is other guidance in Beway that adds confusion to the mix and, effectively, applies an “implicit minority discount.” In discussing the application of a marketability discount, the Court stated:

McGraw’s technique was, first, to ascertain what petitioners’ shares hypothetically would sell for, relative to the net asset values of the corporations, if the corporate stocks were marketable and publicly traded; and second, to apply a discount to that hypothetical price per share in order to reflect the stock’s actual lack of marketability.

Note that the valuation date in Beway was in 1986 (for further reference, see Statutory Fair Value: #6 Applicability of Marketability Discounts in New York on www.ValuationSpeak.com). The appellate decision in Beway was rendered in December 1995. Valuation theory and concepts have evolved considerably since 1986 or 1995. But we only need to look at the evidence to realize what happened in Beway. Kenneth McGraw was an expert for the corporation in Beway. The technique he applied was clearly a minority interest technique. Application of a marketability discount based on reference to restricted stock studies derives a shareholder level value and presumes the inclusion of any minority interest discount. This was apparently not evident to the Court in Beway. The valuation industry was developing rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s. The level of value charts that are so ubiquitous today were first published in 1990, and did not receive wide distribution immediately. Perhaps the court was not presented with this visual, conceptual device.

It should be clear, however, that the application of a marketability discount very clearly moves the valuation from marketable minority/financial control (enterprise levels representing values of entire corporations) to the nonmarketable minority level of value, which clearly is a minority interest value. Application of a marketability discount in a fair value determination, where fair value is interpreted as a proportionate share of the value of the business at the financial control level and as a going concern, clearly has the effect of imposing an unwarranted minority interest discount by another name. This is, again, contrary to guidance of Beway.

Mandating the imposition of a ‘minority discount’ in fixing the fair value of the stockholdings of dissenting minority shareholders in a close corporation is inconsistent with the equitable principles developed in New York decisional law on dissenting stock holder statutory rights.

Partial Consideration of Built-In Gain Liability

The Mahler blog post summarized the result in Justice Friedman’s opinion:

Justice Friedman next turns to Janet’s argument that Referee Crespo erred by not calculating the BIG discount at 100% assuming liquidation upon the valuation date. Janet argued that the Manhattan trial court was bound to follow the Manhattan (First Department) appellate court’s ruling in Wechsler v. Wechsler, 58 AD3d 62 (1st Dept 2008), a matrimonial “equitable distribution” case in which the court applied a 100% BIG discount, rather than the Brooklyn (Second Department) appellate court’s Murphy decision upon which Referee Crespo relied. Justice Friedman notes that the Murphy decision expressly distinguishes Wechsler on grounds equally applicable in Giaimo, namely, there was no issue presented or expert testimony in Wechsler about reducing the BIG taxes to present value. ”Given the lack of precedent in this [First] Department on the issue of whether the BIG should be reduced to present value,” Justice Friedman writes, “the support for that approach in the Second Department, and the factual support in the record for the 10 year projection, the Court does not find that the Special Referee committed legal error in following the present value approach.”

Justice Friedman rejected Robert’s contention that there should be no BIG deduction, stating that Robert relied largely on cases from other states that refuse to consider the BIG unless the corporation was actually undergoing liquidation at the valuation date.

These cases treat an assumed liquidation as inconsistent with valuation of the corporation as an ongoing concern. While the reasoning has much to recommend it, New York follows the contrary view that it is irrelevant whether the corporation will actually liquidate its assets and that the court, in valuing a close corporation, should assume that a liquidation will occur.

Some additional background is appropriate. First, both experts for Janet concluded that 100% of the embedded BIG liability should be considered (i.e., deducted) in their determinations of net asset value. I concluded that 40% of the BIG liability should be considered as a liability. This conclusion was supported by a series of calculations and market evidence regarding the 2007 market for apartment buildings in Manhattan.

I wrote an article in 1998, following the issuance of the Davis case in U.S. Tax Court. The article, “Embedded Capital Gains in C Corporation Holding Companies,” was published in Valuation Strategies, November/December, 1998.

An important conclusion of the article was that, in fair market value determinations involving C corporation asset holding companies (like EGA and FAV), the usual negotiations between hypothetical buyers and sellers would result in a conclusion of consideration of 100% of the BIG liability. This is true when buyers have the choice of buying assets inside a corporate wrapper and purchasing identical assets in “naked form,” or without any issues of BIG. The article shows that the only way that buyers can get equivalent investment returns between the two choices, buying an asset in a corporate wrapper that has embedded BIG and purchasing the “naked asset,” is by charging the full amount of the embedded capital gain. And the article makes no assumption about the potential ability of a buyer to convert the C corporation to an S corporation and hold for ten years until the embedded BIG “goes away.” Simply put, buyers who have the alternative choice of acquiring identical “naked assets” won’t agree to that concept.

Janet’s counsel cross-examined me fairly hard on this issue, attempting to show that I was inconsistent between the article and the treatment in Giaimo. However, a critical assumption is made in reaching the article’s conclusion of charging 100% of the embedded BIG in C corporation asset holding companies:

When analyzing the impact of embedded capital gains in C corporation holding companies, one must examine that impact in the context of the opportunities available to the selling shareholder(s) of those entities. One must also consider the realistic option that potential buyers of the stock of those entities must be assumed to have – that of acquiring similar assets directly, without incurring the problems and issues involved with embedded capital gains in a C corporation.

At the valuation date, the market for comparable Manhattan apartment buildings was very tight. There had been only a handful of transactions in the market, which consisted of many thousands of buildings, in the last year. Brokers we spoke with indicated that because of the nature of the market, and because EGA and FAV owned multiple properties each, there would likely be competitive bidding that would enable the stock of the corporations to be sold with a sharing of the BIG liability. In other words, comparable “naked assets,” i.e., apartment buildings in Manhattan outside corporate wrappers like EGA and FAV, were not available. The Special Referee was convinced by this evidence that there was sufficient liquidity as a result that no marketability discount should be applied (see discussion of the marketability discount above).

Having reached this conclusion, the question became one of how much “sharing” of the BIG liability would be appropriate in a determination of statutory fair value. Recall that we were instructed by counsel that fair value should be determined as the functional equivalent of fair market value on a financial control basis.

- In Murphy, a case involving a real estate holding company with an embedded BIG of $11.6 million, the court allowed a discount of $3.4 million, or about 29.3% of the BIG. This was based on a present value calculation assuming liquidation of the underlying properties in 19 years assuming no growth in value. The implied discount rate was 6.7%. (Matter of Murphy (United States Dredging Corp.), 74 AD3d 815, 2010 NY Slip Op 04794 (2d Dept June 1, 2010))

Based on the court’s analysis in Murphy, I presented an analysis based on the facts of the Giaimo case with the following assumptions.

- The properties would grow in value at an expected rate of 2.5%.

- The properties would be liquidated at the end of a ten year holding period. This was based on assumptions in the underlying real estate appraisals.

- The discount rate used was 10% based on a small premium to the discount rates used in the real estate appraisals.

- The combined capital gains tax rate (federal, state and city) was 45.63%.

Given these assumptions, the present value of the expected future embedded capital gains tax represented 49.4% of the embedded BIG at the valuation date. Just to be clear, that means that for each dollar of embedded capital gain, the analysis suggests reducing net asset value by 49.4 cents. My conclusion, based on this analysis and others presented in court, was that the liability should be 40 cents of each dollar of BIG.

The Special Referee concluded that the appropriate BIG should be about 50% based on an analysis similar to that outlined above. Expected growth was 3% per year (not compounded), for ten years, and with a 10% discount rate.

This finding was affirmed by Justice Friedman’s opinion.

Conclusion

Justice Friedman agreed with the conclusion of no marketability discount in Giaimo, but she reached that conclusion without tackling the problem of the unclear and misguided (by faulty valuation evidence) conclusion regarding the applicability of marketability discounts in statutory fair value determinations. The application of a marketability discount in a statutory fair value determination in New York would have the economic effect of imposing, albeit implicitly, an undesired minority interest discount. I’ll be careful with terminology here. In the fifth post in the statutory fair value series on ValuationSpeak.com (The Implicit Minority Discount), we talked about an “implicit minority discount” in Delaware, which is a different concept entirely.

Since I know that my writings on fair value are being read with interest by an increasing readership, let me go back to my comments in the first post I wrote in the statutory fair value series on ValuationSpeak.com where I said:

At the outset of this series of posts on statutory fair value, let me be clear: I am agnostic with respect to what fair value should be in any particular state. That is a matter of statutory decision-making and judicial interpretation. As a business appraiser, what I hope is that the collective (statutory and judicial) definitions of fair value are clear and able to be expressed in the context of valuation theory and practice.

In my experience, disagreements over the applicability (or not) of certain valuation premiums or discounts provide the source of significant differences of opinion between counsel for dissenting shareholders and, unfortunately, between business appraisers. Because fair value is ultimately a legal concept, appraisers should consult with counsel regarding their legal interpretation of fair value in each jurisdiction.

I was not “for” or “against” a marketability discount in Giaimo. I was “for” the determination of fair value as the functional equivalent of fair market value at the financial control level of value (and on a going concern basis). My engagement instructions from counsel called for this determination. I am “for” clear judicial guidance for fair value determinations that is consistent with prevalent valuation and financial theory. I hope that debate over this continuing series on statutory fair value will help this process along in New York and other states, as well.

The Special Referee’s determination of the BIG liability was clearly in line with both the precedent treatment in Murphy and the economic reality of the marketplace for apartment dwellings in Manhattan at the valuation date.

It remains to be seen if there will be an appeal in the matter.

This article originally appeared on the blog www.ValuationSpeak.com.