Selecting a Business Appraiser

Business appraisal is both an art and a science, and Revenue Ruling 59-60 reinforces this point upon a full reading of the complete document. The concepts of the willing buyer and the willing seller, as well as the basic eight factors to consider requiring careful analysis in each case, are broadly recognized. However, Revenue Ruling 59-60 needs to be properly recognized as setting forth the theory for the appraisal of closely held corporations, and appropriately highlights the difficulty in applying that theory in practice.

In Section 3, Approach to Valuation, the Ruling states:

Often, an appraiser will find wide difference of opinion as to the fair market vale of a particular stock. In resolving such differences, he should maintain a reasonable attitude in recognition of the fact that valuation is not an exact science. A sound valuation will be based upon all the relevant facts, but the elements of common sense, informed judgment and reasonableness must enter into the process of weighing those facts and determining their aggregate significance.

The appraiser must exercise his judgment as to the degree of risk attaching to the business of the corporation that issued the stock, but that judgment must be related to all of then other factors affecting value.

In Section 6, Capitalization Rates, the Ruling goes on to say:

A determination of the proper capitalization rate presents one of the most difficult problems in valuation.… Thus, no standard tables of capitalization rates applicable to closely held corporations can be formulated.

The thoughtful concepts of reasonableness, judgment, and consideration resonate throughout Revenue Ruling 59-60. Indeed, some form of the word “consider” appears approximately 31 times. The body of knowledge that allows for that thoughtful consideration can be found in the certifications and professional designations that relate to business valuation.

Professional Credentials

There are several credentials or professional designations that are applicable to business valuation and related subjects. Professional credentials include the following designations:

Accredited Senior Appraiser (ASA). This designation is granted by the American Society of Appraisers (“ASA”). The American Society of Appraisers is a multi-disciplinary organization (including members in real estate, business valuation, fine arts, machinery and equipment and gemology), and the Accredited Senior Appraiser designation initially requires passing an ethics exam and a course and examination on the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice. Once those two requirements are met, the applicant must pass or demonstrate acceptable equivalency for a series of principles of valuation courses. Upon successful completion of the courses, an individual must have a minimum of five years of full-time equivalent appraisal experience. Additionally, candidates must submit a representative appraisal report for review by the organization. (www.appraisers.org)

Accredited in Business Valuation (ABV). This designation is granted by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (“AICPA”). The AICPA is the national professional association for Certified Public Accountants in the United States. The additional designation of ABV requires that members hold a valid CPA certificate, and pass a comprehensive business valuation examination. Also, substantial involvement in at least six business valuation engagements or evidence of 150 hours is required.

(https://us.aicpa.org/interestareas/forensicandvaluation/membership)

Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA). This designation is granted by the National Association of Certified Valuatos and Analysts (“NACVA”). The CVA designation requires the successful completion of a 5-day Business Valuation and Certification course, a proctored exam, and a case study, and two years experience as a CPA. (www.navca.com)

Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA). This designation is granted by the CFA Institute. To earn the CFA Charter, you must pass through the CFA Program, a graduate-level, self-study program that provides a broad curriculum with professional conduct requirements, culminating in a series of three sequential exams. The CFA program is not structured as an appraisal program. Rather, charter holders are typically employed as securities analysts, portfolio managers or investment bankers and consultants. The securities analyst approach to the body of knowledge includes ethical and professional standards, quantitative methods, economics, financial reporting and analysis, corporate finance, equity investments, fixed income analysis, derivatives, alternative investments and portfolio management and wealth planning. (www.cfainstitute.org)

Chartered Business Valuator (CBV). This designation is granted by The Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators (“CICBV”). In order to achieve the CBV designation, an individual must complete six courses offered by the CICBV, accumulate at least 1,500 hours of business and securities valuation work experience, and successfully pass the membership entrance exam. (www.cicbv.ca)

Experience

Experience counts, and the professional credentialing requirements highlight that important aspect of training. However, while a 5-year time-in-grade may be sufficient to grant a professional credential,

long-term experience really shows up upon examination of the appraiser’s depth and breadth of assignments undertaken. Experience is also evident in a more subtle way: the interaction of the appraiser with other professionals in his own firm. Since it is difficult to build a business appraisal practice around a limited number of industries, the larger appraisal firms provide the benefit of experience at the firm level, which helps ensure the necessary quality control.

Experience also counts in answering the question: Should we hire an industry expert for this engagement, or is it preferable to hire a valuation expert? Given valuation expertise and broad industry perspective, specific industry expertise provides an element of comfort. However, in most independent valuation situations, industry expertise alone is an inadequate level of qualification unless supplemented by valuation knowledge and breadth of industry experience.

The Top 5 Things an Attorney Should Know When Selecting a Business Appraiser

Define the project. In order for the appraiser to schedule the work, set the fee, and understand the client’s specific needs, the attorney needs to provide some basic benchmark information, such as: a description of the specific ownership interest to be appraised (number of shares, units, bonds); an understanding of the level of value for the interest being appraised; a specification of the valuation date, which may be current, or may be a specific historical date; a description of the purpose of the appraisal (informing the appraiser why the client needs an appraisal and how the report will be used).

Insist on an appraiser with experience and credentials. Each business appraisal is unique and experience counts. Most business valuation firms are generalists rather than industry specialists, but the experience gained in discussing operating results and industry constraints with a broad client base gives the appraisal firm substantial ability to understand the client’s special situation. Credentials do not guarantee performance, but they do indicate a level of professionalism for having achieved and maintained them. Attorneys should insist upon them.

Involve the appraiser early on. Even in straightforward buy-sell agreements, family limited partnerships, or corporate reorganizations, it is helpful to seek the advice of the appraiser before the deal is set, to see if there are key elements of the contract document that could be modified to provide a more meaningful appraisal to the client.

Ensure that your expert’s report can withstand a Daubert challenge. In Daubert (Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 113 S.Ct. 2786 (1993)), the Supreme Court noted several factors that might be considered by trial judges when faced with a proffer of expert (scientific) testimony. Several factors were mentioned in Daubert which can assist triers of fact in determining the admissibility of evidence under Rule 702, including:

- Whether the theory or technique in question can be (and has been) tested

- Whether it has been subjected to peer review and publication

- The known or potential error rate of the method or technique

- The existence and maintenance of standards controlling its operation

- The underlying question: Is the method generally accepted in the technical community?

Expect the best. In most cases, the fee for appraisal services is nominal compared to the dollars at risk. The marginal cost of getting the best is negligible. Attorneys can help their appraiser do the best job possible by ensuring full disclosure and expecting an independent opinion of value. The best appraisers have the experience and credentials described above, but recognize the delicate balance between art and science that enables them to interpret the qualitative responses to due-diligence interviews and put them in a stylized format that quantifies the results.

The Top 3 Things a Business Owner Should Know When Selecting a Business Appraiser

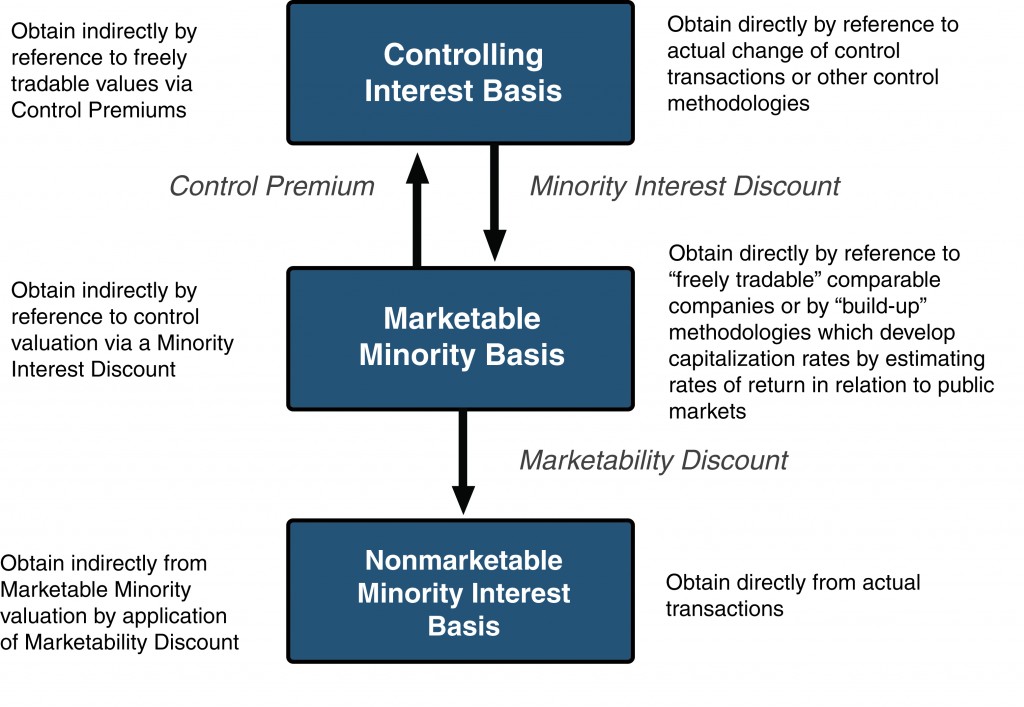

Understand the levels of value. There is no such thing as “the value” of a closely held business. That is an implicit assumption in the field of business appraisal. Yet, business appraisers are engaged to develop a reasonable range of value for client companies. Confusion over an appraiser’s basis of value, either by appraisers or by users of appraisal reports, can lead to the placing of inappropriately high or low values on a subject equity interest. The unfortunate result of such errors can include the overpayment of estate taxes, contested estate tax returns, and ESOP transactions that prove uneconomical or unlawful. Therefore, it is essential that both business appraisers and the parties using appraisals be aware of the correct basis of value and that appropriate methodologies be followed in deriving the conclusion of value for any interest being appraised.

The levels of value chart is a conceptual model used by many appraisers to describe the complexities of behavior of individuals and businesses in the process of buying and selling businesses and business interests. It attempts to cut through the detailed maze of facts that give rise to each individual transaction involving a particular business interest and to describe, generally, the valuation relationships that seem to emerge from observing thousands upon thousands of individual transactions.

Basic valuation theory suggests that there are three levels of value applicable to a business or business ownership interest:

- Controlling interest basis refers to the value of the enterprise as a whole

- Marketable minority interest basis refers to the value of a minority interest, lacking control, but enjoying the benefit of liquidity as if it were freely tradable in an active market

- Nonmarketable minority interest basis refers to the value of a minority interest, lacking both control and market liquidity

The relationship between these three levels of value is depicted in the Figure below.

Levels of value can co-exist, with one shareholder owning a controlling interest, one a marketable minority interest, and one a nonmarketable minority interest. Clearly, the appropriate level of value depends upon the purpose of the valuation. Nevertheless, understanding the three primary levels of value is critical to the valuation process both from the standpoint of the appraiser and the client.

Understand the difference between your compensation rate of return and your investment rate of return. Business owners will often combine these two concepts into one return, typically in the form of compensation. Since it all comes from the same pot (the company), why does this matter? Your business appraiser will help you segregate these two concepts, since the appraisal will be dependent upon a proper investment rate of return, after consideration of a proper compensation rate of return (i.e., compensation expense). The business owner/operator is due both returns, but there is a clear distinction between the two.

The business appraiser is not your advocate. Your attorney is your advocate, and your appraiser must be independent of the consequences of the conclusion of value. If litigated, opposing counsel is certain to ask the appraiser if he received any guidance with regard to a suggested conclusion or range of values that was expected.

The Top 3 Things an Accountant Should Know When Selecting a Business Appraiser

Avoid the conflict of interest trap. Your tax and audit clients will appreciate the fact that you consider your relationship too important to jeopardize by performing a business valuation that almost certainly would be challenged as having at least a perceived conflict of interest. The one time appraisal assignment will be thought of as a relatively minor fee-income generating project in context with on-going annual tax and audit work. Locate an independent business appraiser with whom you can work, and you will feel comfortable in providing a referral to a professional who does not also provide the tax and audit services.

Avoid the lack of experience trap. Business appraisals have become increasingly detailed and sophisticated as the profession has grown. Accounting firms typically build their book of business on tax and audit work. If your internal staff does not include professionals dedicated solely to business valuation, the part-time nature of generating marginal additional fees by business appraisal may come back to haunt you and your client, typically in court.

Help your client distinguish between a business appraisal and a real estate appraisal. Many of the corporate entities appraised either own or rent the real estate where the business is operated. For a successful operating business, the most meaningful valuation is typically based on some measure of capitalized earnings, rather than the value of the underlying real estate. However, the accountant will recognize that some businesses, due to the nature of their operations, are characterized more by their underlying assets, and less so by their earnings power. This is true for asset-holding entities, and for some older family businesses with marginal earnings but with appreciated real estate on the books. Many business appraisers are not asset appraisers, but may need to consider a qualified real estate appraisal in the business valuation process.