Video: Corporate Finance Basics for Directors and Shareholders

Below is the transcript of the above video, Corporate Finance Basics for Directors and Shareholders. In this video, Travis W. Harms, CFA, CPA/ABV, senior vice president of Mercer Capital, offers a short, yet thorough, overview of corporate finance fundamentals for closely held and family business directors and shareholders.

Hi, my name is Travis Harms, and I lead Mercer Capital’s Family Business Advisory practice. I welcome and thank you for taking a few minutes to listen to our discussion, “Corporate Finance Basics for Directors and Shareholders.”

Corporate finance does not need to be a mystery. In this short presentation, I will give you the tools and vocabulary to help you think about some of the most important long-term decisions facing your company.

To do this, we review the foundational concepts of finance, identify the three key questions of corporate finance, and then leverage those three questions to help think strategically about the future of your company.

Let’s start with the fundamentals of finance: return and risk.

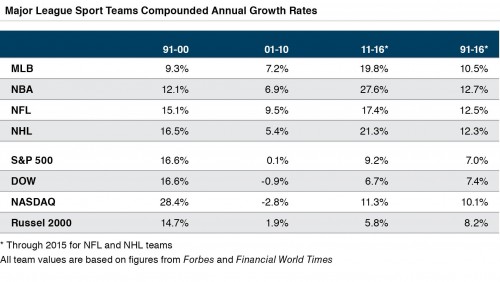

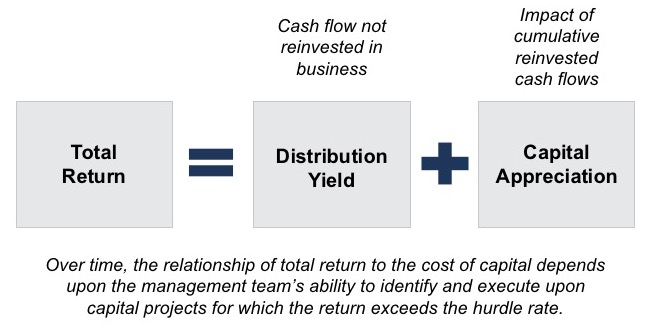

Return measures the reward for making an investment. Investment returns come in two different forms: the first, distribution yield, is a measure of the annual distributions generated by an investment. The second, capital appreciation, measures the change in the value of an investment over time. Total return is the sum of these two components.

This is important because two investments may generate the same total return, although in very different forms. Some investments, like bonds, emphasize current income, while others, like venture capital, are all about capital appreciation. Many investments promise a mix of current income and future upside.

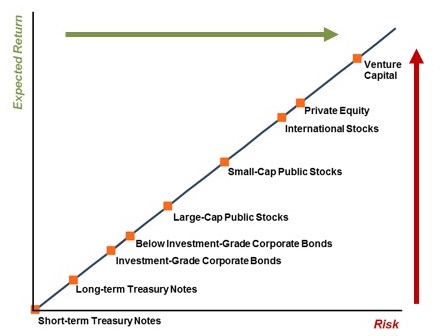

The most basic law of corporate finance is that return follows risk.

The above chart compares the expected return required by investors and the risk of different investments. Since investment markets are generally efficient, higher returns are available only by accepting greater risk.

But what is risk?

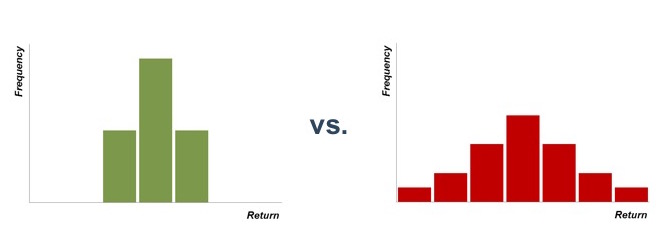

Simply put, risk is the fact that future investment outcomes are unknown. The wider the distribution of potential outcomes, the greater the risk.

While both investments represented above are risky, the dispersion of outcomes for the investment on the right is wider than that on the left, so the investment on the right is riskier. Because it is riskier, it will have a higher expected return. Now, whether that higher return actually materializes is unknown when the investment is made – that’s what makes it risky.

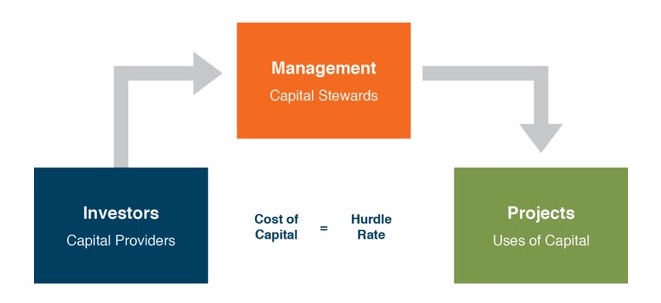

For a particular company, the expected return is referred to as the company’s cost of capital. From a corporate finance perspective, the company stands between investors (who are potential providers of capital) and investment projects (which are potential uses of the capital provided by investors). The cost of capital is the price paid to attract capital from investors to fund investment projects.

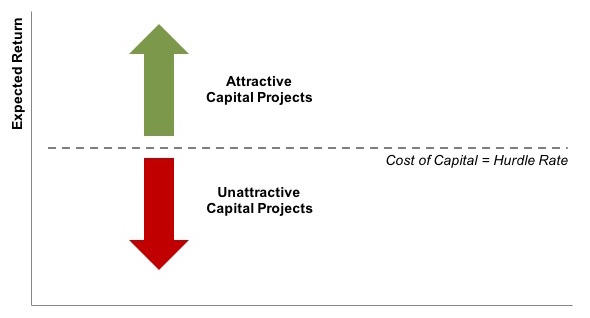

When evaluating potential investment projects, corporate managers use the cost of capital as the hurdle rate to measure the attractiveness of the project.

Next, we will move on to the three essential questions of corporate finance.

Corporate managers and directors should always be thinking about three fundamental corporate finance questions:

- First, what is the most efficient mix of capital? This the capital structure question – what is the mix of debt and equity capital that minimizes the company’s overall cost of capital?

- Second, what projects merit investment? This is the capital budgeting question – how does the company identify investment projects that will deliver returns in excess of the hurdle rate?

- And third, what mix of returns do shareholders desire? This is the distribution policy question – what is the appropriate mix of current income and future upside for the company’s investors?

Let’s start with the first question: what is the most efficient mix of capital?

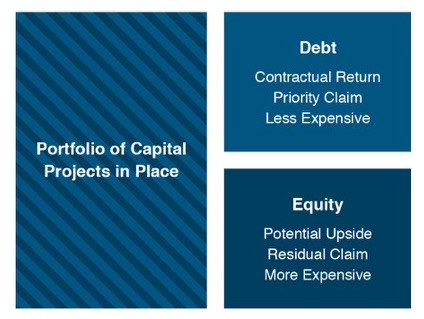

You can think of the company’s assets as a portfolio of individual capital projects – that is the left side of the balance sheet. The right side of the balance sheet tells us how the company has paid for those investments. The only two funding options are debt and equity. Because debt holders are promised a contractual return and have a priority claim on the assets and cash flows of the company, debt is less expensive than equity, which has only a residual claim on the company.

You can think of the company’s assets as a portfolio of individual capital projects – that is the left side of the balance sheet. The right side of the balance sheet tells us how the company has paid for those investments. The only two funding options are debt and equity. Because debt holders are promised a contractual return and have a priority claim on the assets and cash flows of the company, debt is less expensive than equity, which has only a residual claim on the company.

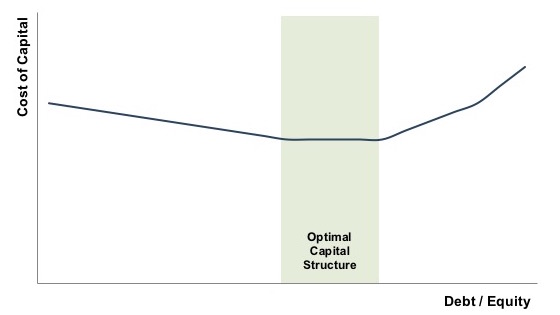

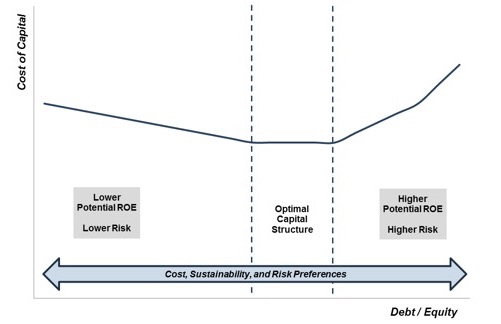

If debt is cheaper than equity, you might assume that a company could reduce its cost of capital by simply issuing more and more debt. That is not the case, however. As the company uses more debt, the risk of both the debt and the equity increase. And, as we said earlier, greater risk will cause both debt and equity investors to demand higher returns.

Eventually, because the cost of both components is increasing, the overall blended (or weighted average) cost of capital increases with increasing reliance on debt. The goal of capital structure analysis is to identify the optimal capital structure, or the mix of debt and equity that minimizes the company’s cost of capital.

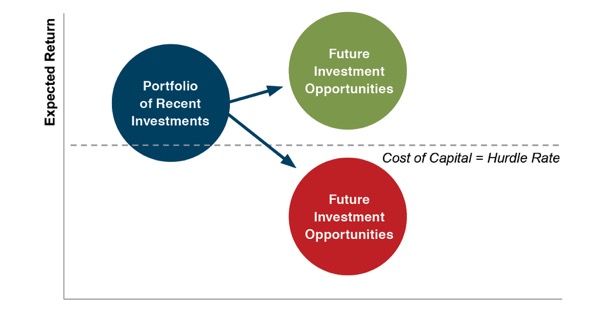

Now let’s move on to the second question: what investment projects should the company devote capital to? At the strategic level, management’s job is to survey the landscape of potential investment projects, choosing those that are strategically compelling and financially favorable.

From a financial perspective, a potential investment project is attractive if the return from the expected cash flows meets or exceeds the hurdle rate, which is the cost of capital.

The appropriate pace of investment for a company is therefore related to the availability of attractive investment projects.

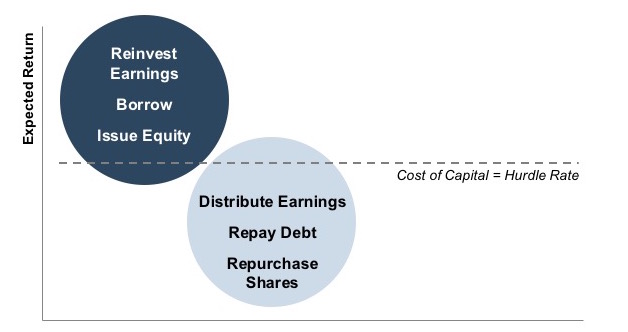

If attractive investment projects are abundant, the company should reinvest earnings into new projects, and, if yet more attractive projects are available, borrow money and/or issue new equity to fund the investment. If attractive investment projects are scarce, however, the company should return capital to investors through debt repayment, distribution of earnings, or share repurchase. We can now begin to see how the three questions are related to one another. Capital structure decisions are always made relative to the need for investment capital.

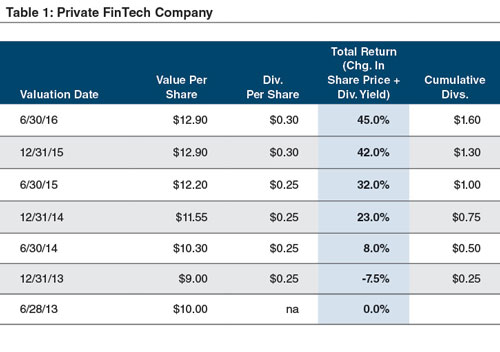

This inter-relationship is illustrated above within the context of the two components of total return we discussed earlier. Distribution yield provides a current return to shareholders from cash flow not reinvested in the business, while the cumulative impact of reinvested cash flows is manifest in the capital appreciation component of total return.

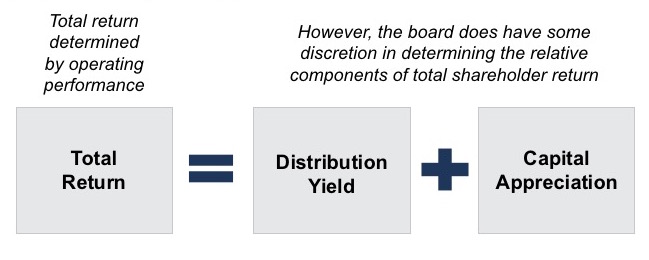

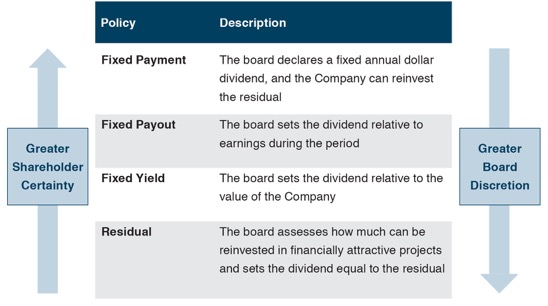

This leads us to the final corporate finance question, which relates to distribution policy: what mix of returns do shareholders desire?

While the operating performance of the business ultimately determines total return, the board can tailor the components of that return to fit shareholder preferences better.

We’ve primarily been looking through the rearview mirror to assess what the company has done in the past; now it’s time to look through the windshield and think prospectively about capital structure, capital budgeting, and distribution policy going forward.

First, capital structure. In the long-run, the optimal capital structure will balance the cost of funds, flexibility, availability, and the risk preferences of the shareholders. Now, that last factor – shareholder preferences – should not be overlooked. Family businesses should not be managed for some abstract textbook shareholder, but rather for the actual family members that own the business.

For example, while an under-leveraged capital structure reduces potential return on equity, it also reduces the risk of bankruptcy. Some shareholders may view this tradeoff favorably even if it can be demonstrated to be “sub-optimal” from a textbook standpoint.

Second, capital budgeting. The attractiveness of investment opportunities should be evaluated with reference to future – and not past – returns. Beyond the threshold question of whether such opportunities are in fact available, managers and directors should also consider financial and management constraints under which the company is operating and the desire of shareholders for diversification.

Since family business shareholders lack ready liquidity for their shares, they may have a greater desire to diversify their investment holdings away from the family business. In other words, they may favor foregoing some otherwise attractive investment opportunities in order to increase distributions that would help shareholders diversify.

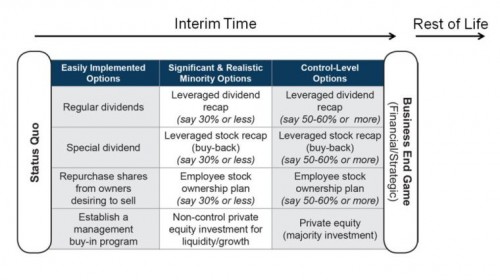

Third, distribution policy. The appropriate form and amount of distributions should reflect shareholder preferences within the context of capital budgeting and capital structure decisions. Perhaps most importantly, a clearly communicated distribution policy enhances predictability for shareholders, and shareholders like predictability.

Family business shareholders should know which of the four basic options describes their company’s distribution policy.

Family business shareholders should know which of the four basic options describes their company’s distribution policy.

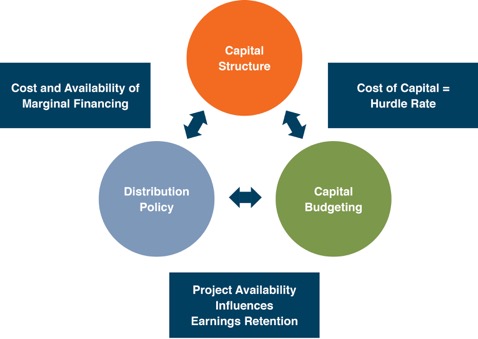

Finally, to recap, each of the three questions relates to one another.

The company’s capital structure influences the cost of capital, which serves as the hurdle rate in capital budgeting decisions. The availability of attractive investment projects, in turn, determines whether earnings should be retained or distributed. Lastly, distribution policy affects, and is affected by, the cost and availability of marginal financing sources.

For a deeper dive into some of the topics we talked about, we have several whitepapers and other resources that you can download from our website.

The good news is that you do not have to have an advanced degree in finance to be an informed director or shareholder. With the concepts from this presentation, you can make relevant and meaningful contributions to your company’s strategic financial decisions. In fact, we suspect that a roomful of finance “experts” can actually be an obstacle to the sort of multi-disciplinary, collaborative decision-making that promotes the long-term health and sustainability of the company. Our family business advisory practice gives directors and shareholders a vocabulary and conceptual framework for thinking about and making strategic corporate finance decisions.

Again, my name is Travis Harms and I thank you for listening. If you’d like to continue the discussion further or have any questions about how we may help you, please give us a call.

Travis W. Harms, CFA, CPA/ABV

(901) 322-9760

Emerging Community Bank M&A Trends in 2017

As summer came to an end, the U.S. was treated with a historic event as the first total solar eclipse crossed the country since 1918. The timing of the event had social media and news outlets buzzing in a traditionally sleepy news month. For many, the event exceeded all expectations; for others, it was a dud that didn’t live up to the hype. My personal experience was a bit of both. The minutes of darkened skies were definitely memorable, but things returned to normal quickly as the sun shone brightly only minutes after.

Traditional M&A Trends

Community bank M&A trends also seem mixed. Rising regulatory burdens, weak margins from a historically low interest rate environment and heightened competition have crimped ROEs for years. Many pundits have predicted a rapid wave of consolidation and the demise of community banks in the years since the financial crisis. However, the pace of consolidation the last few years is consistent with the past three decades in which roughly 3-4% of the industry’s banks are absorbed through M&A yearly. The result is many fewer banks—5,787 at June 30 compared to about 15,000 in the mid-1980s when meaningful industry consolidation got underway.

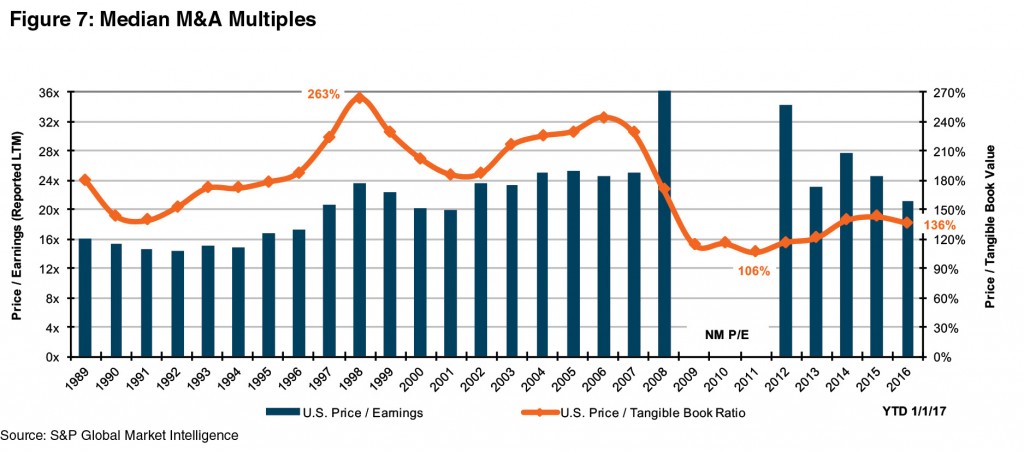

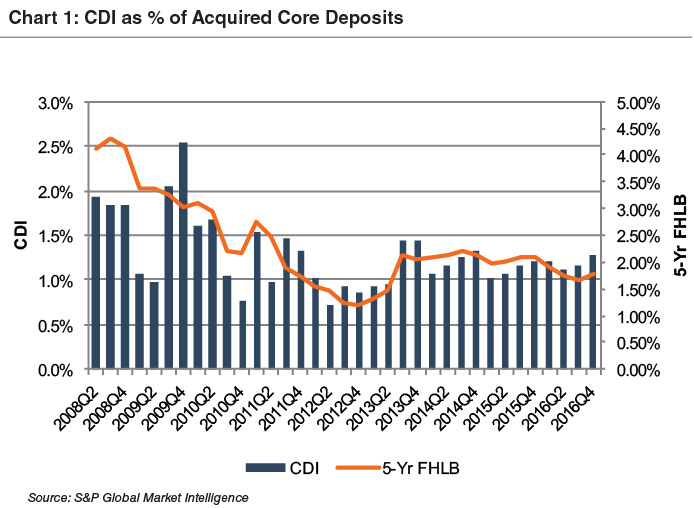

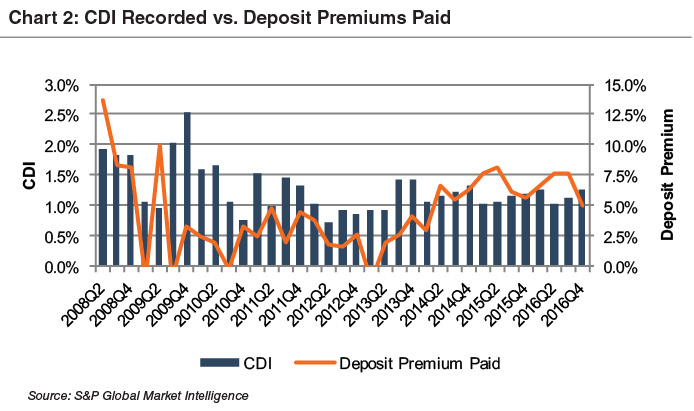

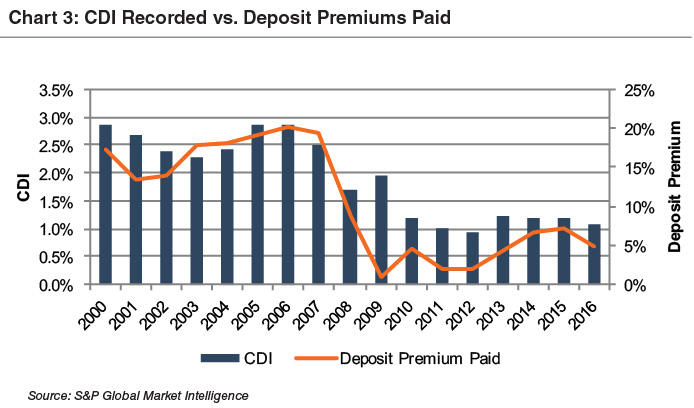

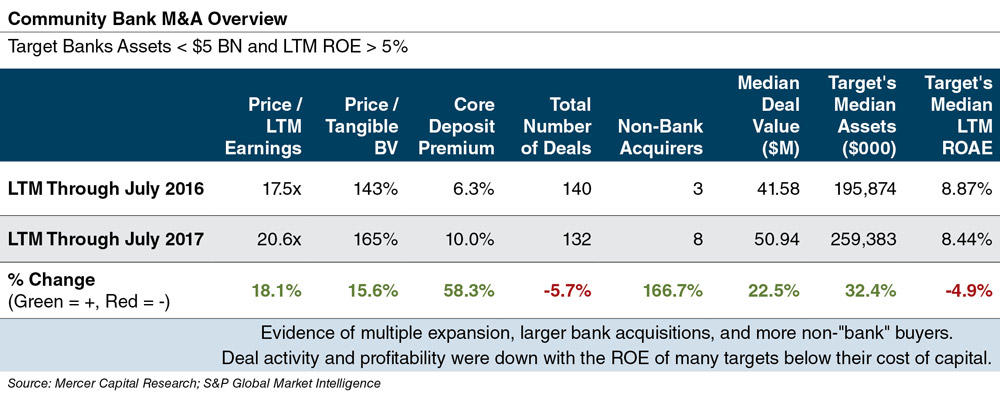

Somewhat surprisingly, the spike in bank stock prices following the November 2016 national elections did not cause M&A to accelerate. As would be expected, acquisition multiples increased in 2017 because publicly traded acquirers could “pay-up” with appreciated shares. As seen in the table on the next page, the median P/E and P/TBV multiples and the median core deposit premium increased for the latest twelve months (LTM) ended July 31, 2017 compared to the year ago LTM period. The ability of buyers—at least the publicly traded ones—to more easily meet sellers’ price expectations seemingly would lead more banks to sell. However, that has not happened as the pace of consolidation declined slightly to 132 transactions in the most recent LTM period compared to 140 in the year ago LTM time frame.

FinTech’s Impact on M&A

Another emerging M&A trend is the presence of non-traditional bank acquirers, which include private investor groups, non-bank specialty lenders, and credit unions. While a FinTech company has not yet announced an acquisition of a U.S. bank this year, several FinTechs have announced they are applying for a bank charter (SoFi, VaroMoney), and in the U.K., Tandem has agreed to acquire Harrods Bank.

So far, FinTech acquisitions of banks have been limited to a few acquisitions by online brokers and Green Dot Corporation’s acquisition of a bank in 2011. While FinTech companies have yet to emerge as active buyers, there have been some predictions that could change if regulatory hurdles can be navigated. Some FinTech companies are well-funded or have access to additional funding that could be tapped for a bank acquisition. In addition, an overlay of enhancing financial inclusion for the under-banked could mean bank transactions may not be as far-fetched as some may think.

Beyond serving as potential acquirers, FinTech continues to emerge as an important piece of the community banking puzzle of how to engage customers through digital channels as the costly branch banking model sees usage decline year-after-year. Many FinTechs are eager to partner with banks to scale their operations for greater profitability, thereby better positioning themselves for a successful exit down the road.

Consistent with this trend, we have also seen some acquirers (and analysts) comment on FinTech as a benefit of a transaction, as opposed to (or at least in addition to) the historical focus on geographic location, credit quality, asset size, and profitability. We will be watching to see if FinTech initiatives, whether internally developed or acquired, become a bigger driving force in bank M&A. If so, acquisitions of FinTech companies by traditional banks may increase (as discussed more fully in this article).

As these trends grow in importance, buyers and sellers will have to grapple with unique valuation and transaction issues that require each to fully understand the value of the seller and the buyer, assuming a portion of the consideration consists of the buyer’s shares. Whether that buyer includes a traditional bank whose stock is private or a non-bank buyer, such as a specialty lender or FinTech company, we have significant valuation and transaction expertise to help your bank understand the deal landscape and the strategic options available to it.

If we can be of assistance, give us a call to discuss your needs in confidence.

This article originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, August 2017.

Fairness Opinions Do Not Address Regrets

Sometimes deals can go horribly wrong between the signing of a merger agreement and closing. Buyers can fail to obtain financing that seemed assured; sellers can see their financial position materially deteriorate; and a host of other “bad” things can occur. Most of these lapses will be covered in the merger agreement through reps and warranties, conditions to close, and if necessary, the nuclear trigger that can be pushed if negotiations do not produce a resolution: the material adverse event clause (MAEC). And MAEC = litigation.

Bank of America’s (BAC) 2008 acquisition of Countrywide Financial Corporation will probably be remembered as one of the worst transactions in U.S. history, given the losses and massive fines that were attributed to Countrywide. BAC management regretted the follow-on acquisition of Merrill Lynch so much that the government held CEO Ken Lewis’ feet to the fire when he threatened to trigger MAEC in late 2008 when large swaths of Merrill’s assets were subjected to draconian losses. BAC shareholders bore the losses and were diluted via vast amounts of common equity that were subsequently raised at very low prices.

Another less well-known situation from the early crisis years is the acquisition of Charlotte-based Frist Charter Corporation (FCTR) by Fifth Third Bancorp (FITB). The transaction was announced on August 16, 2007 and consummated on June 6, 2008. The deal called for FITB to pay $1.1 billion for FCTR, consisting 30% of cash and 70% FITB shares with the exchange ratio to be set based upon the five day closing price for FITB the day before the effective date. At the time of the announcement FITB expected to issue ~20 million common shares; however, 45 million shares were issued because FITB shares fell from the high $30s immediately before the merger agreement was signed to the high teens when it was consummated. (The shares would fall to a closing low of $1.03 per share on February 20, 2009; the shares closed at $25.93 per share on July 14, 2017.) The additional shares were material because FITB then had about 535 million shares outstanding. Eagerness to get a deal in the Carolinas may have caused FITB and its advisors to agree to a fixed price / floating exchange ratio structure without any downside protection.

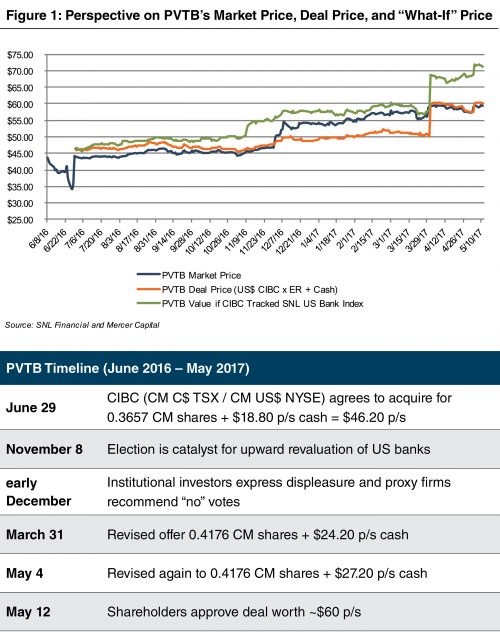

A more recent example of a deal that may entail both buyer and seller regrets is Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce’s (CIBC) now closed acquisition of Chicago-based Private Bancorp Inc. (PVTB). A more detailed account of the history of the transaction can be found here. The gist of the transaction is that PVTB entered into an agreement to be acquired by CIBC on June 29, 2016 for 0.3657 CIBC shares that trade in Toronto (C$) and New York (US$), and $18.80 per share of cash. At announcement the transaction was valued at $3.7 billion, or $46.20 per share. As U.S. bank stocks rapidly appreciated after the November 8 national elections, institutional investors began to express dismay because Canadian stocks did not advance. In early December, proxy firms recommended shareholders vote against the deal. A mid-December shareholder vote was then postponed.

CIBC subsequently upped the consideration two times. On March 31, 2017, it proposed to acquire PVTB for 0.4176 CIBC shares and $24.20 per share of cash. On May 4, CIBC further increased the cash consideration by $3.00 to $27.20 per share because its shares had trended lower since March as concerns intensified about the health of Canada’s housing market. On May 12, shareholders representing 66% of PVTB’s shares approved the acquisition.

Figure 1 highlights the trouble with the deal from PVTB shareholders’ perspective. While the original deal entailed a modest premium, the performance of CIBC’s shares and the sizable cash consideration resulted in little change in the deal value based upon the original terms. On March 30 the deal equivalent price for PVTB was $50.10 per share, while the market price was $59.00 per share. The following day when PVTB upped the consideration the offer was valued at $60.11 per share; however, the revised offer would have been worth nearly $69 per share had CIBC’s shares tracked the SNL U.S. Bank Index since the agreement was announced on June 29. On May 11 immediately before the shareholder vote the additional $3.00 per share of cash offset the reduction in CIBC’s share price such that transaction was worth ~$60 per share, while the “yes-but” value was over $71 per share had CIBC’s shares tracked the U.S. index since late June.

Fairness opinions do not cover regret, but there are some interesting issues raised when evaluating fairness from a financial point of view of both PVTB and CIBC shareholders. (Note: Goldman Sachs & Co. and Sandler O’Neill & Partners provided fairness opinions to PVTB as of June 29 and March 30. The registration statement does not disclose if J.P. Morgan Securities provided a fairness opinion as the lead financial advisor to CIBC. The value of the transaction on March 30 when the offer was upped the second time was $4.9 billion compared to CIBC’s then market cap of US$34 billion.)

Fairness is a Relative Concept

Some transactions are not fair, some are reasonable, and others are very fair. The qualitative aspect of fairness is not expressed in the opinion itself, but the financial advisor conveys his or her view to management and a board that is considering a significant transaction. When the PVTB deal was announced on June 29, it equated to $46.35 per share, which represented premiums of 29% and 14% to the prior day close and 20-day average closing price. The price/tangible book value multiple was 220%, while the P/E based upon the then 2016 consensus estimate was 18.4x. As the world existed prior to November 8, the multiples appeared reasonable but not spectacular.

Fairness Does not Consider 20-20 Hindsight Vision

Fairness opinions are qualified based upon prevailing economic conditions; forecasts provided by management and the like and are issued as of a specific date. The opinion is not explicitly forward looking, while merger agreements today rarely require an affirmation of the initial opinion immediately prior to closing as a condition to close. That is understandable in the context that the parties cut a deal that was deemed fair to shareholders from a financial point of view when signed. In the case of PVTB, the future operating environment (allegedly) changed with the outcome of the national election. Banks were seen as the industry that would benefit from a combination of lower corporate tax rates, less regulation, faster economic growth, and higher rates as part of the “reflation trade.” A reasonable deal became not so reasonable if not regrettable when the post November 8 narrative excluded Canadian banks. Time will tell if PVTB’s earning power really will improve, or whether the move in bank stocks was purely speculative.

Subtle Issues Sometimes Matter

Although not a major factor in the underperformance of CIBC’s shares vis-à-vis U.S. banks, the Canadian dollar weakened from about C$1.30 when the merger was announced on June 29 to C$1.33 in early December when the shareholder meeting was postponed. When shareholders voted to approve the deal on May 12 the Canadian dollar had eased further to C$1.37. The weakness occurred after the merger agreement was signed and the initial fairness opinions were delivered on June 29. Sometimes seemingly small financial issues can matter in the broad fairness mosaic, but only with the clarity of hindsight.

Waiting for a Better Deal is not a Fairness Consideration

Although a board will consider the business case for a transaction and strategic alternatives, a fairness opinion does not address these issues. The original registration statement noted that Private was not formally shopped. The deal was negotiated with CIBC exclusively, which twice upped its initial offer before the merger agreement was signed in June. It was noted that the likely potential acquirers of PVTB were unable to transact for various reasons. The turn of events raises an interesting look-back question: should the board have waited for a better competitive situation to develop? We will never know; however, the board is given the benefit of the doubt because it made an informed decision given what was then known.

The Market Established a Fair Price

Institutional shareholders had implicitly rejected what became an unfair deal by early December when PVTB’s shares traded well above the deal price. The market combined with the “no” recommendation of three proxy firms forced PVTB to delay the special meeting. The increase in the consideration in late March pushed the deal price to a slight premium to PVTB’s market price. CIBC increased the cash consideration an additional $3.00 per share in early May to offset a decline in CIBC’s shares that had occurred since the consideration was increased in March. The market had in effect established its view of a fair price. While CIBC could have declined to up its offer yet again, it chose to offset the decline.

Relative Fairness from CIBC’s Perspective Fluctuated

What appeared to be a reasonable deal from CIBC’s perspective in June became exceptionally fair by early December, if the market is correct that the earning power of U.S. commercial banks will materially improve as a result of the November 8 election. CIBC’s financial advisors can easily change assumptions in Excel spreadsheets to justify a higher price based upon better future earnings than originally projected, but would doing so be “fair” to CIBC shareholders whether expressed euphemistically or formally in a written opinion? So far the evidence of higher earning power is indirect via the market placing a higher multiple on current bank earnings in expectation of much better earnings that will not be observable until 2018 or 2019. That as a stand-alone proposition is an interesting valuation attribute to consider as part of a fairness analysis both from PVTB’s and CIBC’s perspective.

Conclusion

Hindsight is easy; predicting the future is a fool’s errand. Fairness opinions do not opine where securities will trade in the future. Some PVTB shareholders may have regrets that CIBC was not a U.S. commercial bank whose shares would have

out-performed CIBC’s after November 8. CIBC shareholders may regret the PVTB acquisition even though U.S. expansion has been a top priority. The key, as always in any M&A transaction, will be execution over the next several years rather than the PowerPoint presentation. Higher rates, a faster growing U.S. economy and the like will help, too, if they occur.

We at Mercer Capital cannot predict the future, but we have over three decades of experience in helping boards assess transactions as financial advisors. Sometimes paths and fairness from a financial point of view seem clear; other times they do not. Please call if we can assist your company in evaluating a transaction.

This article originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, July 2017.

Creating Value at Your Community Bank Through Developing a FinTech Framework

This discussion is adapted from Section III of the new book Creating Strategic Value Through Financial Technology by Jay D. Wilson, Jr., CFA, ASA, CBA.

I enjoyed some interesting discussions between bankers, FinTech executives, and consultants at the FinXTech event in NYC in late April. One dominant theme at the event was a growing desire of both banks and FinTech companies to find ways to work together. Whether through partnerships or potential investments and acquisitions, both banks and FinTech companies are coming to the conclusion that they need each other. Banks control the majority of customer relationships, have a stark funding advantage and know how to navigate the maze of regulations, while FinTechs represent a means to achieve low-cost scaling of new and traditional bank services. So one key question emerging from these discussions is: Who will survive and thrive in the digital age? As one recent Tearsheet article that I was quoted in asked: Should fintech startups buy banks? Or as another article discussed: Will banks be able to compete against an army of Fintech startups?

Build, Partner, or Acquire

Banks face a conundrum of whether they should build their own FinTech applications, partner, or acquire. FinTech companies face similar questions, though the questions are viewed through the prism of customer acquisition rather than applications. Non-control investments of FinTech companies by banks represent a hybrid strategy. Regulatory hurdles limit the ability of FinTech companies to make anything more than a modest investment in banks absent bypassing voting common stock for non-voting common and/or convertible preferred.

While these strategic decisions will vary from company to company, the stakes are incredibly high for all. We can help both sides navigate the decision process.

As I noted in my recently published book, community banks collectively remain the largest lenders to both small business and agricultural businesses, and individually, they are often the lifeblood for economic development within their local communities. Yet the number of community banks declines each year through M&A, while some risk loosened deposit relationships as children who no longer reside in a community where the bank is located inherit the financial assets of deceased parents. FinTech can loosen those bonds further, or it can be used to strengthen relationships while providing a means to deliver services at a lower cost.

Where to Start

In my view, it is increasingly important for bankers to develop a FinTech framework and be able to adequately assess potential returns from FinTech partnerships. Similar to other business endeavors, the difference between success and failure in the FinTech realm is often not found in the ideas themselves, but rather, in the execution.

Banks face a conundrum of whether they should build their own FinTech applications, partner, or acquire.

While a bank’s FinTech framework may evolve over time, it will be important to provide a strategic roadmap for the bank to optimize chances of success. Within this framework, there are a number of important steps:

- Determining which FinTech niche to pursue;

- Identifying potential FinTech companies/partners;

- Developing a business case for those potential partners and their solutions; and

- Executing the chosen strategy.

For a number of banks, the use of FinTech and other enhanced digital offerings represents a potential investment that uses capital but may be deemed to have more attractive returns than other traditional bank growth strategies. Community banks typically underperform their larger brethren (as measured by ROE and ROA) because fee income is lower and expenses are higher as measured by efficiency ratios. Both areas can be enhanced through deployment of a number of FinTech offerings/solutions.

The Importance of a Detailed IRR Analysis

The decision process for whether to build, partner, or acquire requires the bank to establish a rate of return threshold, which arguably may be higher than the institution’s base cost of capital given the risk that can be associated with FinTech investments. The range of returns for each strategy (build, partner, or acquire) for a targeted niche (such as payments or wealth management) provides a framework to help answer the question how to proceed just as is the case with the question of how to deploy capital for organic growth, acquisitions, and shareholder distributions. The same applies for FinTech companies, though often the decision is in the context of whether to accept dilutive equity capital.

A detailed analysis, including an IRR analysis, helps a bank determine the financial impact of each strategic decision and informs the optimal course.

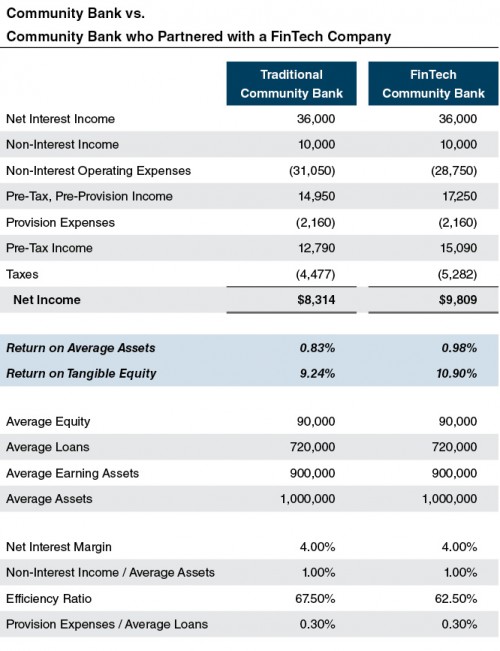

While each option presents a unique set of considerations and execution issues/risks, a detailed analysis, including an IRR analysis, helps a bank determine the financial impact of each strategic decision and informs the optimal course. A detailed analysis also allows the bank to compare its FinTech strategy to the bank’s more traditional growth strategies, strategic plan, and cost of capital. See the table to the right for an example of a traditional community bank compared to a bank who has partnered with a FinTech company.

Questions Regarding Partnering

Beyond the strategic decisions and return analyses, some additional questions remain for community banks that consider FinTech partners, including:

- Is the bank comfortable with the FinTech company’s risk profile?

- What will the regulatory reaction be?

- Who will maintain the primary relationship with the customer?

- Is the FinTech partnership consistent with the bank’s long-term strategic plan (a key topic noted in the OCC’s whitepaper on supporting innovation)?

Questions Regarding Acquiring

Should the community bank ultimately decide to invest in a FinTech partner a number of other key questions emerge, such as:

- What is the valuation of the FinTech company?

- How should the investment be structured?

- What preferences or terms should be included in the shares purchased from the FinTech company?

- Should the bank obtain board seats or some control over the direction of the FinTech Company’s operations?

How Mercer Capital Can Help

To help both banks and FinTech companies execute their optimal strategies and create maximum value for their shareholders, we have a number of solutions here at Mercer Capital. We have a book that provides greater detail on the history and outlook for the FinTech industry, as well as containing targeted information to help bankers answer some of the key questions discussed here.

Mercer Capital has a long history of working with banks. We are aware of the challenges facing community banks. With ROEs for the majority below 10% and their cost of capital, it has become increasingly difficult for many banks to deliver adequate returns to shareholders even though credit costs today, are low. Being both a great company that delivers benefits to your local community, as well as one that delivers strong returns to shareholders is a difficult challenge. Confronting the challenge requires a solid mix of the right strategy as well as the right team to execute that strategy.

No one understands community banks and FinTech as well as Mercer Capital.

Mercer Capital can help your bank craft a comprehensive value creation strategy that properly aligns your business, financial, and investor strategy. Given the growing importance of FinTech solutions to the banking sector, a sound value creation strategy needs to incorporate FinTech into it and Mercer Capital can help.

- We provide board/management retreats to educate you about the opportunities and challenges of FinTech for your institution.

- We can identify which FinTech niches may be most appropriate for your bank given your existing market opportunities.

- We can identify which FinTech companies may offer the greatest potential as partners for your bank.

- We can provide assistance with valuations should your bank elect to consider investments or acquisitions of FinTech companies.

No one understands community banks and FinTech as well as Mercer Capital. We are happy to help. Contact me to discuss your needs.

This article first appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, June 2017.

Infographic: 5 Reasons to Conduct a Shareholder Survey

Of all the well-worn clichés that should be retired, “maximizing shareholder value” is surely toward the top of the list. Since private companies don’t have constant public market feedback, attempts to “maximize” shareholder “value” are destined to end in frustration. While private company managers are not able to gauge instantaneous market reaction to their performance, they do know who their shareholders are. Wouldn’t it be better to make corporate decisions based on the characteristics and preferences of actual flesh-and-blood shareholders than the assumed preferences of generic shareholders that exist only in textbooks? If so, there is no substitute for simply asking. Here’s a quick list of five good reasons for conducting a survey of your shareholders.

For more information about conducting a shareholder survey, check out the article “5 Reasons to Conduct a Shareholder Survey.”

To discuss how a shareholder survey or ongoing investor relations program might benefit your company, learn more about our Corporate Finance Consulting or give us a call.

Corporate Finance Basics for Directors and Shareholders

To craft an effective corporate strategy, management and directors must answer the three fundamental questions of corporate finance.

- The Capital Structure question: What is the most efficient mix of capital?

- The Capital Budgeting question: Which projects merit investment?

- The Dividend Policy question: What mix of returns do shareholders desire?

These questions should not be viewed as the special preserve of the finance team. To maintain a healthy governance culture, all directors and shareholders need to have a voice in how these long-term decisions are made. This presentation is an example of the topics that we cover in education sessions with directors and shareholders. The purpose of the presentation is to provide directors and shareholders with a conceptual framework and vocabulary to help contribute to answering the three fundamental questions.

5 Reasons to Conduct a Shareholder Survey

Of all the well-worn clichés that should be retired, “maximizing shareholder value” is surely toward the top of the list. Since private companies don’t have constant public market feedback, attempts to “maximize” shareholder “value” are destined to end in frustration. While private company managers are not able to gauge instantaneous market reaction to their performance, they do know who their shareholders are. Wouldn’t it be better to make corporate decisions based on the characteristics and preferences of actual flesh-and-blood shareholders than the assumed preferences of generic shareholders that exist only in textbooks? If so, there is no substitute for simply asking. Here’s a quick list of five good reasons for conducting a survey of your shareholders.

- A survey will help you learn about your shareholders. A well-crafted shareholder survey will go beyond mere demographic data (age and family relationships) to uncover what deeper characteristics owners share and what characteristics distinguish owners from one another. We recently completed a survey for a multi-generation family company, and not surprisingly, one of the findings was that the shareholder base included a number of distinct “clienteles” or groups of shareholders with common needs and risk preferences. What was surprising was that the clienteles were not defined by age or family tree branch, but rather by the degree to which (a) the shareholder’s household income was concentrated in distributions from company stock, and (b) the shareholder’s personal wealth was concentrated in company stock. The boundary lines for the resulting clienteles did not fall where management naturally assumed.

- A survey will help you gauge shareholder preferences. The results from a shareholder survey will help directors and managers move away from abstract objectives (like “maximizing shareholder value”) toward concrete objectives that actually take into account shareholder preferences. For example, what are shareholder preferences for near-term liquidity, current distributions, and capital appreciation? Identifying these preferences will enable directors and shareholders to craft a coherent strategy that addresses actual shareholder needs. Conducting a survey does not mean that the board is off-loading its fiduciary responsibility to make these decisions to the shareholders: a survey is not a vote. Rather, it is a systematic means for the board to solicit shareholder preferences as an essential component of deliberating over these decisions.

- A survey will help educate the shareholders about the strategic decisions facing the company. While a survey provides information about the shareholders to the company, it also inevitably provides information about the company to shareholders. In our experience, the survey is most effective if preceded by a brief education session that reviews the types of questions that will be asked in the survey. Shareholders do not need finance degrees to be able to understand the three basic decisions that every company faces: (1) how should we finance operations and growth investments (capital structure), (2) what investments should we be making (capital budgeting), and (3) what form should shareholder returns take (distribution policy). Educated shareholders can provide valuable input to directors and managers, and will prove to be more engaged in management’s long-term strategy.

- A survey will help establish a roadmap for communicating operating results to shareholders. Public companies are required by law to communicate operating results to the markets on a timely basis, and many public companies invest significant resources in the investor relations function because they recognize that it is critical that the markets understand not just the bare “what happened” of financial reporting, but the “why” of strategy. Oddly, for most private companies, there is no roadmap for communicating results, and investor relations is either ignored or consists of reluctantly answering potentially-loaded questions from disgruntled owners (who may, frankly, enjoy being a nuisance). A shareholder survey can be a great jumping-off point for a more structured process for proactively communicating operating results to shareholders. An informed shareholder base that understands not only “what happened” but also “why” is more likely to take the long-view in evaluating performance.

- A survey gives a voice to the “un-squeaky” wheels. A shareholder’s input should not be proportionate to the volume with which the input is given. While the squeaky wheel often gets the grease, it is prudent for directors and managers to solicit the feedback regarding the needs and preferences of quieter shareholders. Asking for input from all shareholders through a systematic survey process helps ensure that the directors and managers are receiving a balanced picture of the shareholder base. A confidential survey administered by an independent third party can increase the likelihood of receiving frank (and therefore valuable) responses.

An engaged and informed shareholder base is essential for the long-term health and success of any private company, and a periodic shareholder survey is a great tool for achieving that result. To discuss how a shareholder survey or ongoing investor relations program might benefit your company, give one of our senior professionals a call.

Is FinTech a Threat or an Opportunity?

Adapted from the new book Creating Strategic Value Through Financial Technology by Jay D. Wilson, Jr., CFA, ASA, CBA.

In order to understand how FinTech can help community banks create strategic value, let us take a closer look at the issues facing community banks and discuss how FinTech can help improve performance and valuation. This is significant, particularly in the U.S., as community banks compose an important part of the economy, constitute the majority of banks in the U.S. and are collectively the largest providers of certain loan types such as agricultural and small business lending.

Threats to Community Banks

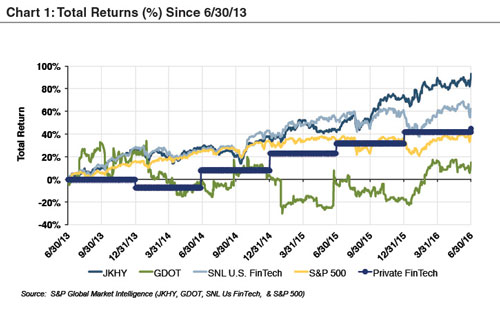

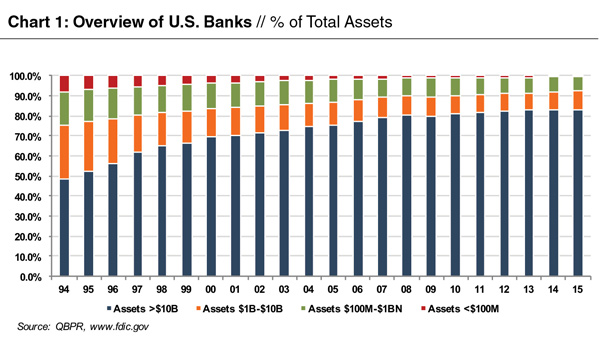

There are nearly 6,000 community banks with 51,000 locations in the U.S. (includes commercial banks, thrifts, and savings institutions). While community banks constitute the vast majority of banks (approximately 90% of U.S. banks have assets below $1 billion), the majority of banking industry assets are controlled by a small number of extremely large banks. These larger banks have acquired assets more quickly than community banks in the last few decades (as shown in Chart 1).

In addition to competition from larger banks and industry headwinds, community bankers are also attempting to assess and respond to the growing threat from the vast array of FinTech companies and startups taking aim at the banking sector. For perspective, a group of community bankers meeting with the FDIC in mid-2016 noted that FinTech poses the largest threat to community banks. One executive indicated that the payment systems “are the scariest” as consumers are already starting to use FinTech applications like Venmo and PayPal to send peer-to-peer payments. Another banker went on to note, “What’s particularly concerning about [the rise of FinTech] for us is the pace of change and the fact that it’s coming so quickly.”

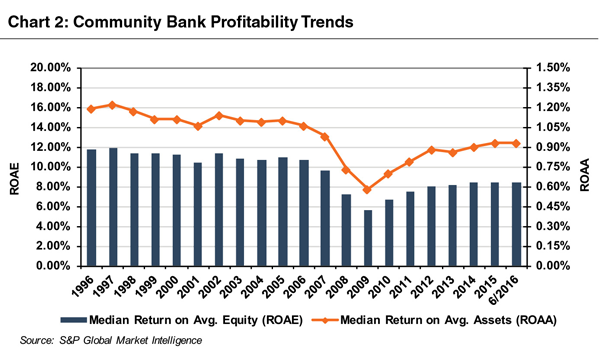

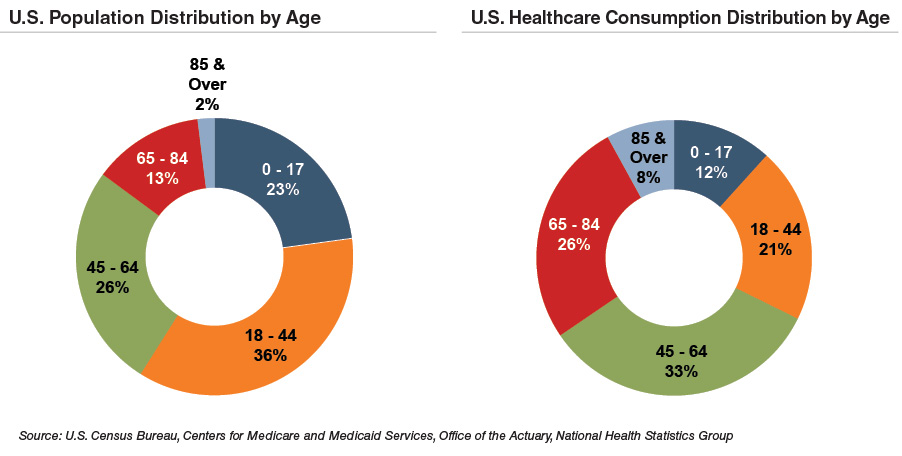

These significant competitive pressures combined with other industry headwinds such as higher regulatory and compliance costs and a historically low interest rate environment have hurt returns on equity (ROEs) for community banks (Chart 2).

Opportunities for Community Banks

While many bankers view FinTech as a significant threat, FinTech also has the potential to assist the community banking sector. FinTech offers the potential to improve the health of community banks by enhancing performance and improving profitability and ROEs back to historical levels.

One way to better understand how FinTech can assist community banks is to understand where the Big Banks are outperforming smaller banks. Big Banks (defined as those with assets greater than $5 billion) have outperformed community banks consistently for many years. In the 20-year period from 1996 to 2016, Big Banks reported a higher return on asset (ROA) than community banks in each period except for 2009 (the depths of the financial crisis). Interestingly though, the source of outperformance is not due to net interest margin, perhaps the most common performance metric that bankers often focus on. Community banks had consistently higher net interest margins than Big Banks in each year over that 20-year period (1996-2016). Rather, the outperformance of the Big Banks can be attributed to their generation of greater non-spread revenues (i.e., non-interest income) and lower non-interest expense (i.e., lower efficiency ratios).

FinTech and Non-Interest Income and Efficiency Ratios

While FinTech can benefit community banks in a number of areas, FinTech offers some specific solutions where community banks have historically underperformed: non-interest income and efficiency. To enhance non-interest income, community banks may consider a number of FinTech innovations in niches like payments, insurance, and wealth management. Since many community banks have minimal personnel and legacy systems in these areas, they may be more apt to try a new FinTech platform in these niches. For example, a partnership with a robo-advisor might be viewed more favorably by a community bank as it represents a new source of potential revenue, another service to offer their customers and it will not cannibalize their existing trust or wealth management staff since they have minimal existing wealth management personnel.

FinTech can also enhance efficiency ratios and reduce expenses for community banks. Branch networks are the largest cost of community banks and serving customers through digital banking costs significantly less than traditional in-branch services and interactions with customers. For example, branch networks make up approximately 47% of banks’ operating costs and 54% of that branch expenditure goes to staffing. Conversely, the cost of ATM and online-based transactions are less than 10% of the cost of paper-based branch transactions in which tellers are involved. In addition to the benefits from customers shifting to digital transactions, community banks can utilize FinTech to assist with lowering regulatory/compliance costs by leveraging “reg-tech” solutions.

To illustrate the potential financial impact of transitioning customers to digital transactions for community banks, let’s assume that a mobile transaction saves the bank approximately $3.85 per branch transaction. If we assume that FinTech Community Bank has 20,000 deposit accounts and each account shifts two transactions per month to mobile from in-person branch visits, the bank would save approximately $150 thousand per month and approximately $1.8 million annually. These enhanced earnings would serve to enhance efficiency and improve shareholder returns and the bank’s valuation.

Moving beyond non-interest income and efficiency ratios, FinTech also offers a number of other potential benefits for community banks. FinTech can be used to help community banks compete against Big Banks more effectively by minimizing the impact of scale as more customers carry their branch in their pocket. By leveraging FinTech solutions, smaller banks can more easily compete against a large bank’s footprint digitally via the web or a mobile device. FinTech also offers many community banks an opportunity to enhance loan portfolio diversification and regain some market share after years of losing ground in certain segments (such as consumer, mortgage, auto, and student).

FinTech can also provide an additional touch point to improve customer retention and preference. While data is limited, some studies have shown that customer loyalty (i.e., retention) is higher for those customers that use mobile offerings and digital banking (online and mobile) is increasingly preferred by customers. While digital is clearly growing among customer preference, data has also shown that digital-only customers can be less engaged, loyal, and profitable than those who interact with the bank through a combination of interactions across multiple channels (digital, branches, etc.). So community banks that rely more heavily on their branch networks should find it beneficial to add digital services to complement their traditional offerings in order to enhance customer retention and preference.

Change Is Inevitable, Growth Is Optional

As technological advances continue to penetrate the banking industry, community banks will need to leverage technology in order to more effectively market to and serve small businesses and consumers in an evolving environment. Community banks will likely increasingly rely on a model that makes widespread use of ATM’s, the Internet, mobile apps and algorithm driven decision making, enabling them to deliver their services to customers in a streamlined and efficient manner.

Conclusion

Our world is changing quickly. FinTech can represent an opportunity for community banks. Understanding how FinTech will impact your institution and your response is critical today. Many community banks are actively surveying the FinTech landscape and pursuing a strategy to improve their digital footprint and services through partnerships with FinTech companies. Our new book, Creating Strategic Value Through Financial Technology, can help those banks considering their FinTech strategy as it provides information on the FinTech landscape and provides an overview of a few prominent FinTech niches (payments, wealthtech, insurtech, and banktech), case studies of successful (and unsuccessful FinTech companies), as well as an overview of some key ways to value FinTech companies and assess value creation when structuring FinTech acquisitions, investments, and/or partnerships.

Whatever your strategy, understanding how FinTech fits in and adapting to the current environment is incumbent upon any institution that seeks to compete effectively and Mercer Capital will be glad to assist. We have successfully worked with both traditional financial incumbents (banks, insurance, wealth managers) as well as FinTech companies in a number of strategic planning and valuation projects over the years.

This article originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, April 2017.

Buy-Sell Agreements for Investment Management Firms

Every closely held business needs a functional buy-sell agreement, but few need it more than investment management firms. Because RIAs are 1) often very valuable, 2) owned by unrelated parties, and 3) tie ownership returns to employee participation, having an effective ownership agreement is essential for the prosperity and sustainability of the firm. This session discussed the key characteristics and valuation implications of an RIA’s buy-sell agreement, with the purpose of keeping the firm’s ownership focused on mutual economic benefit and to avoid expensive disputes over value.

Matthew R. Crow, ASA, CFA, President, and Brooks K. Hamner, CFA, Vice President, presented at the RIA Institute’s 3rd Annual RIA Central Investment Forum on April 4, 2017.

Strategic Benefits of Stress Testing

“Every decade or so, dark clouds will fill the economic skies, and they will briefly rain gold. When downpours of that sort occur, it’s imperative that we rush outdoors carrying washtubs, not teaspoons. And that we will do.”

– Warren Buffett, Berkshire 2017 Annual Shareholder Letter

While the potential regulatory benefits are notable, stress testing should be viewed as more than just a regulatory check-the-box exercise. The process of stress testing can help bankers find silver (or gold in Warren’s case) linings during the next downturn.

What Stress Testing Can Do For Your Bank

As we have noted before, a bank stress test can be seen as analogous to stress tests performed by cardiologists to determine the health of a patient’s heart. Bank stress tests provide a variety of benefits that could serve to ultimately improve the health of the bank and avoid fatal consequences. Strategic benefits of a robust stress test are not confined merely to the results and structure of the test. A robust stress test can help bank management make better decisions in order to enhance performance during downturns. A bank that has a sound understanding of its potential risks in different market environments can improve its decision making, manage risk appropriately, and have a plan of action ready for when economic winds shift from tailwinds to headwinds.

By improving risk management and capital planning through more robust stress testing, management can enhance performance of the bank, improve valuation, and provide better returns to shareholders. For example, a stronger bank may determine that it has sufficient capital to withstand extremely stressed scenarios and thus can have a game plan for taking market share and pursuing acquisitions or buybacks during dips in the economic, valuation, and credit cycle. Alternatively, a weaker bank may determine that considering a sale or capital raise during a peak in the cycle is the optimal path forward. If the weaker bank elects to raise capital, a stress test will help to assess how much capital may be needed to survive and thrive during a severe economic environment. Beyond the strategic benefits, estimating loan losses embedded within a sound stress test can also provide a bank with a head start on the pending shift in loan loss reserve accounting from the current “incurred loss” model to the more forward-looking approach proposed in FASB’s CECL (Current Expected Credit Loss) model.

Top Down Stress Testing

In order to have a better understanding of the stress testing process, consider a hypothetical “top-down” portfolio-level stress test. While not prescriptive in regards to the particular stress testing methods, OCC Supervisory Guidance noted, “For most community banks, a simple, stressed loss-rate analysis based on call report categories may provide an acceptable foundation to determine if additional analysis is necessary.” The basic steps of a top-down stress test include determining the appropriate economic scenarios, segmenting the loan portfolio and estimating losses, estimating the impact of stress on earnings, and estimating the stress on capital.

While the first step of determining a stressed scenario to consider varies depending upon a variety of factors, one way to determine your bank’s stressed economic scenario could be to consider the supervisory scenarios announced by the Federal Reserve in February 2017. While the more global economic conditions detailed in the supervisory scenarios may not be applicable to community banks, certain detail related to domestic variables within the scenarios could be useful when determining the economic scenarios to model at your bank. The domestic variables include six measures of real economic activity and inflation, six measures of interest rates, and four measures of asset prices.

The 2017 severely adverse scenario includes a severe global recession, accompanied by heightened corporate financial stress (real GDP contraction, rising unemployment, and declining asset values). Some have characterized the 2017 “severe” scenario as less severe than the 2016 scenario (given a relatively higher disposable income growth forecast and a lack of negative short-term yields, which were included in the 2016 economic scenarios). However, CRE prices were forecast to decline more in the 2017 scenario, and those banks more focused on CRE or corporate lending may find the 2017 scenarios more negatively impact their capital and earnings forecasts.

For community banks facing more unique risks that are under greater regulatory scrutiny, such as those with significant concentrations in commercial real estate lending or a business model concentrated in particular niche segments, a top-down stress test can serve as a starting point to build their stress testing process. The current environment may be an opportune time for these banks to plan ahead.

While credit concerns in recent quarters have been minimal and provisions and non-performing asset levels have trended lower for the banking sector as a whole, certain loan segments have shown some signs that the credit pendulum may have reached its apex and reversed course by swinging back in the other direction. REITs were net sellers of property in 2016 for the first time since 2009, and a rising rate environment could pressure capitalization rates higher and underlying commercial real estate asset values lower. Furthermore, banks with longer duration fixed rate loans could face a combination of margin pressure and credit quality concerns as rates rise.

Conclusion

Regulatory guidance suggests a wide range of effective stress testing methods depending on the bank’s complexity and portfolio risk–ranging from “top-down” to “bottom-up” stress testing. The guidance also notes that stress testing can be applied at various levels of the organization including transactional level stress testing, portfolio level stress testing, enterprise-wide level stress testing, and reverse stress testing.

We acknowledge that community bank stress testing can be a complex exercise as it requires the bank to essentially perform the role of both doctor and patient. For example, the bank must administer the test, determine and analyze the outputs of its performance, and provide support for key assumptions/results. There is also a variety of potential stress testing methods and economic scenarios for a bank to consider when setting up their test. In addition, the qualitative, written support for the test and its results is often as important as the results themselves. For all of these reasons, it is important that bank management begin building their stress testing expertise sooner rather than later.

In order to assist community bankers with this complex and often time-consuming exercise, we offer several solutions, including preparing custom stress tests or reviewing ones prepared by banks internally, to make the process as efficient and valuable for the bank as possible.

To discuss your stress testing needs in confidence, please do not hesitate to contact us. For more information about stress testing, click here.

This article originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, March 2017.

2016 and 2017: Buy the Rumor and Sell the News?

Last year was a volatile year for credit and equity markets that saw price moves that more typically play out over a couple of years. The year began with a broad-based sell-off in risk assets that got underway in late 2015 due to concerns about the impact of the then Fed intention to raise short-term rates up to four times, widening credit spreads, and a collapse in oil prices. Credit (i.e., leverage loans and high yield debt) and equities rebounded in March and through the second quarter after market participants concluded that media headlines about potentially sub $20 oil were ridiculous and that the Fed probably would not raise rates four times; or, stated differently—the U.S. economy was not headed for recession. Markets staged the second strong rally of the year immediately following the national elections on November 8th with the surprise election of Donald Trump as the next POTUS, and Republicans holding Congress.

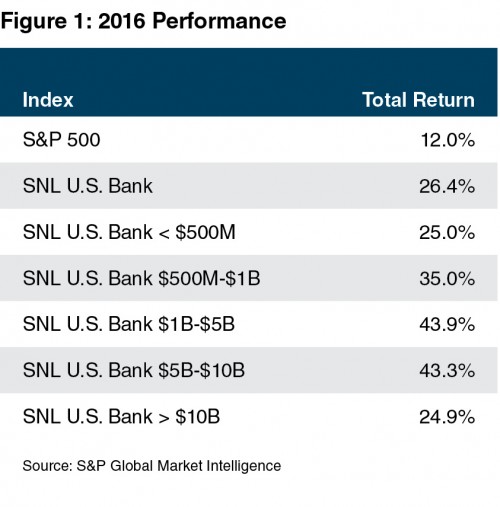

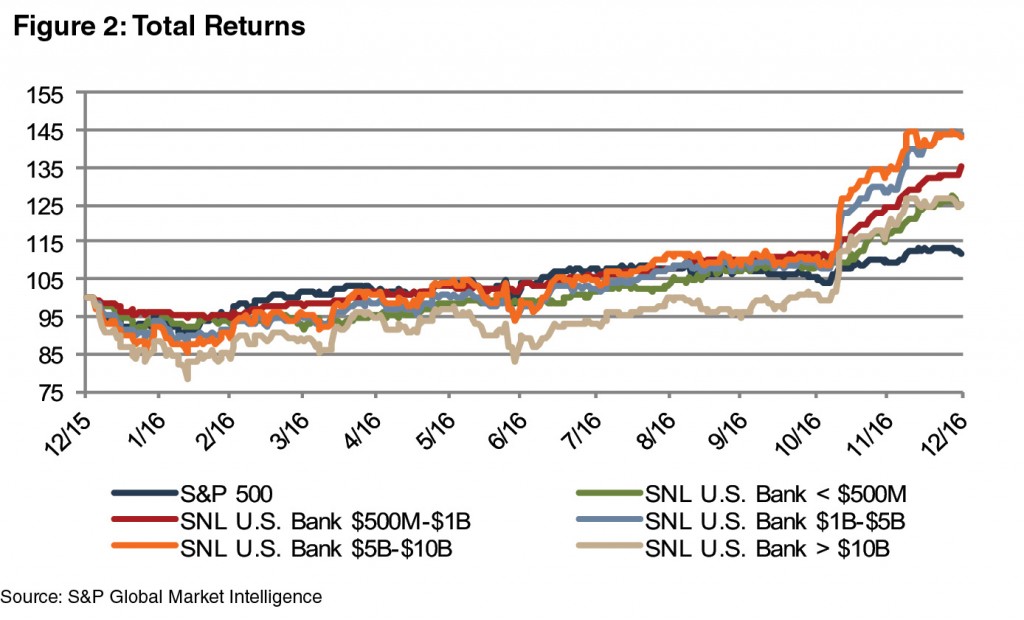

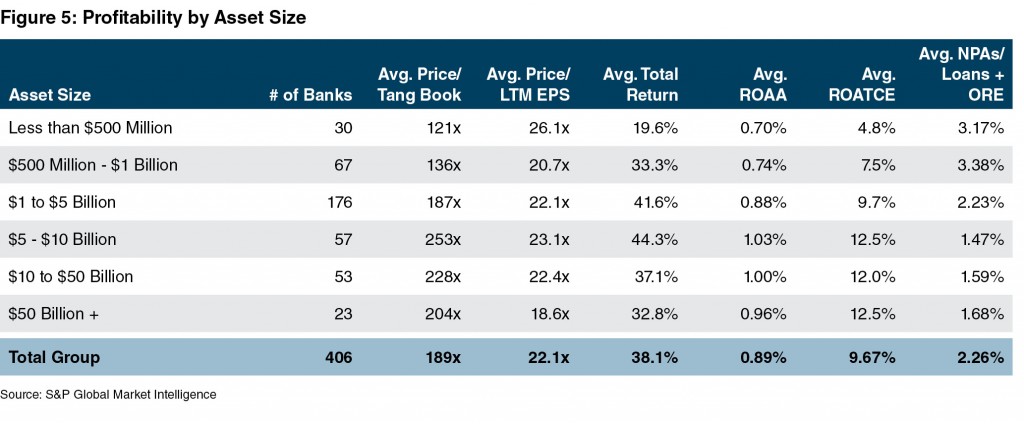

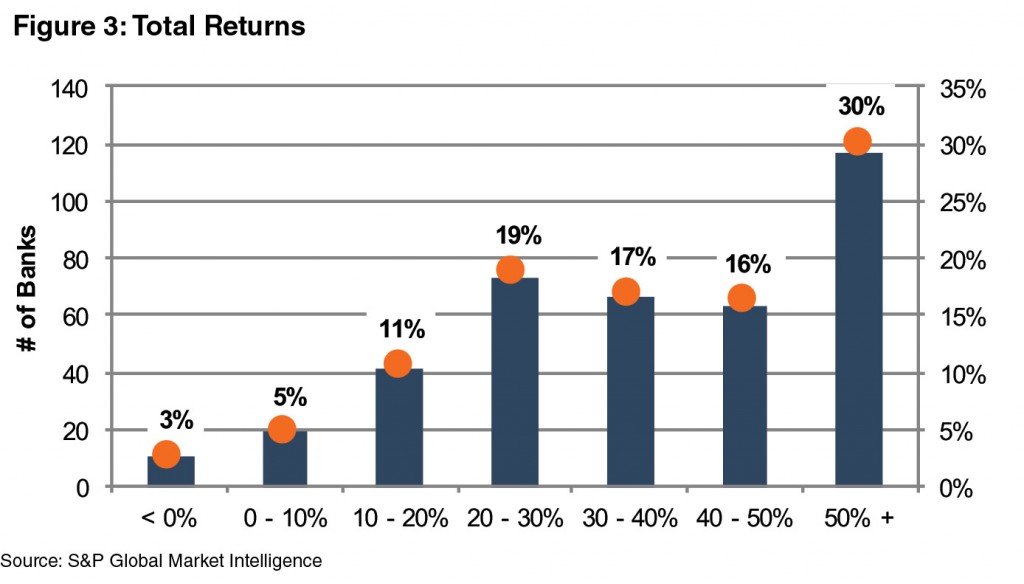

Not surprisingly, the heavily regulated financial sector outperformed the broader market, with bank stocks (as represented by the SNL U.S. Bank Index) gaining 23% versus 5% for the S&P from November 8th through the end of the year. Most of the return for the bank index was realized after the election given the full year total return of 26%. Banks in the $1 to $5 billion and $5 to $10 billion groups led the way in 2016 with total returns on the order of 44% for the year.

The magnitude of the rally in bank stocks was notable because the U.S. economy was not emerging from recession – when bank earnings are near a cyclical trough, poised to turn sharply higher as credit costs fall and loan demand improves.

Last year was a great year for most bank stock investors. Bank returns averaged around 40% in 2016, with 30% of the U.S. banks analyzed (traded on the NASDAQ, NYSE, or NYSE Market exchanges for the full year) realizing total returns greater than 50%. The returns reflected three factors: earnings growth, dividends (or share repurchases that were accretive to EPS), and multiple expansion.

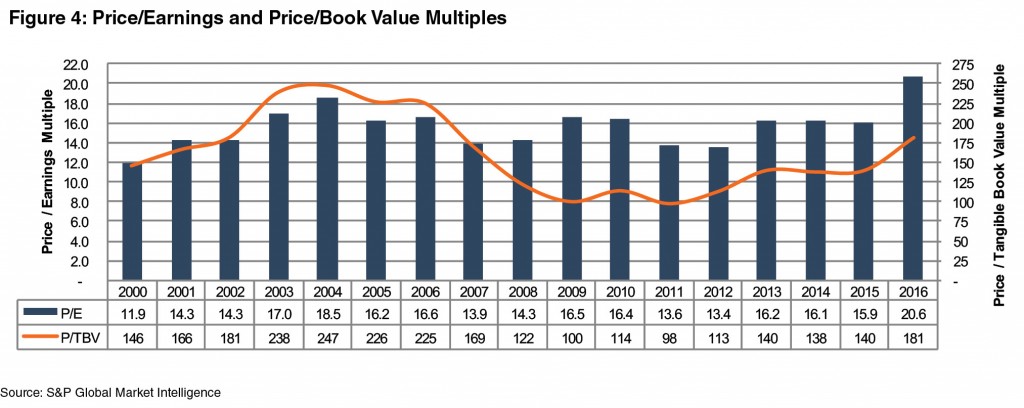

As shown in Figure 4, the median P/E for publicly-traded banks expanded about 30% to 20.6x trailing 12-month earnings at year-end from 15.9x at year-end 2015. Likewise, the median P/TBV multiple expanded to 181% from 140%. While bank stocks closed the year at the highest P/E level seen this century, P/TBV multiples remain below the pre-crisis peak given lower ROEs (ROTCEs), which in turn are attributable to higher capital and lower NIMs.

Figure 5 summarizes profitability by asset size. Banks with assets between $5 and $10 billion were the most profitable on an ROA basis and realized the highest total returns for the year. This group stands to benefit the most from regulatory reform if the Dodd-Frank $10 billion threshold (and $50 billion for SIFIs) is raised. In the most optimistic scenario, the market appears to be discounting that banks’ profitability will materially improve with lower tax rates, higher rates, and less regulation. The corollary to this is that the stocks are not as expensive as they appear because forward earnings will be higher provided credit costs remain modest. Based upon our review, most analysts have incorporated lower tax rates into their 2018 estimates, which accounts for much more modest P/Es based upon 2018 consensus estimates compared to 2017 consensus estimates.

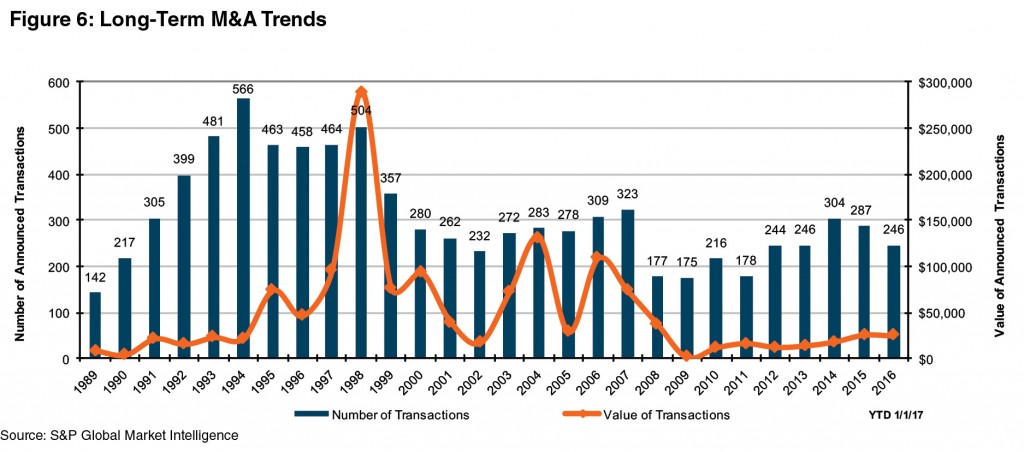

2016 M&A Trends

On the surface, 2016 M&A activity eased modestly from 2014 and 2015 levels based upon fewer transactions announced; however, when measured relative to the number of banks and thrifts at the beginning of the year, 2016 was consistent with the long-running trend of 2-4% of institutions being acquired each year. The 246 announced transactions represented 3.8% of the 6,122 chartered institutions at the beginning of the year compared to 4.5% for 2014 and 4.2% for 2015.

As for pricing, median multiples softened a little bit, but we do not read much into that. Last year, the median P/TBV multiple for transactions in which deal pricing was disclosed eased to 136% compared to 142% in 2015; the median P/E based upon trailing 12 month earnings as reported declined to 21.2x versus 24.4x in 2015.

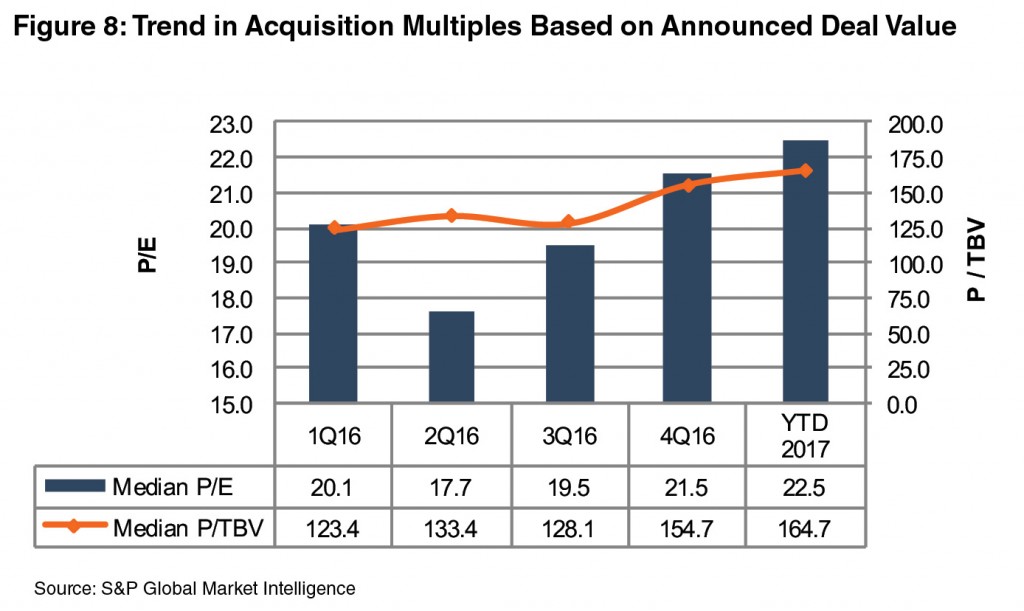

Elevated public market multiples since the national election have set the stage for higher M&A multiples in 2017 as publicly-traded buyers can “pay” a higher price with elevated share prices (Figure 8). The impact of this was seen among some larger transactions announced after the national election compared to when LOIs were announced earlier in the Fall. Activity may not necessarily pick-up with higher nominal prices, however, if would be sellers decide to wait for higher earnings as a result of anticipated increases in rates and lower taxes and regulations. In effect, some may wait for even better values or decide not to sell because ROEs improve sufficiently to justify remaining independent. Time will tell.

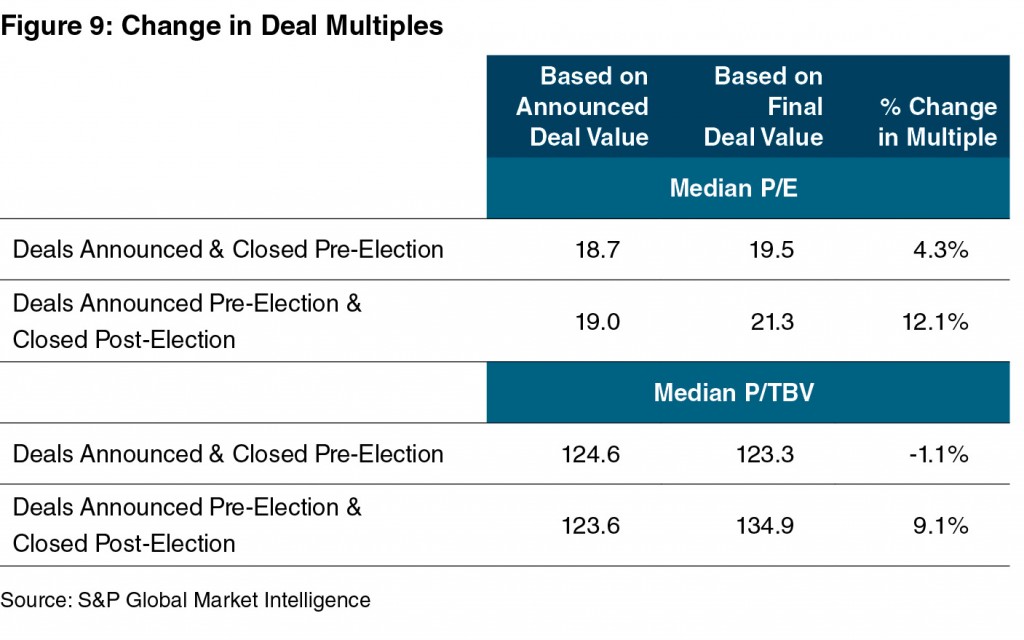

Figure 9 shows the change in deal multiples from announcement to closing and compares the change between deals announced and closed pre-election to those closed post-election. With the run-up in pricing, P/E and P/TBV multiples increased 12% and 9% from announcement to close compared to 4% and a decline of 1% pre-election.

2017 Outlook

No one knows what the future holds, although one can assess probabilities. An old market saw states “buy the rumor; sell the news” which means stocks move before the expected news comes to pass. As of the date of the drafting of this note (February 7), bank stocks are roughly flat in 2017. The stocks have priced in the likelihood of some roll-back in Dodd-Frank, higher short-term and long-term rates, lower tax rates, and a generally more favorable economic backdrop that supports loan growth and asset quality. The magnitude of these likely – but not preordained – outcomes and the timing are unknown. Following a big rally in 2016, returns for bank stocks may be muted in 2017 even if events in Washington and the Fed prove to be favorable for banks.

That said, higher stock prices and investor demand for reasonable yielding sub-debt from quality issuers implies the M&A market for banks should be solid. The one caveat is that there are fewer banks, so a healthy M&A market for banks could still entail fewer transactions than were recorded in 2016.

Mercer Capital is a national business valuation and financial advisory firm. Financial Institutions are the cornerstone of our practice. To discuss a valuation or transaction issue in confidence, feel free to contact us.

This article originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, February 2017.

How to Create Strategic Value in the Current Environment

Against a backdrop of compressed net interest margins, enhanced competition from non-banks, rising regulatory and compliance costs and evolving consumer preferences regarding the delivery of financial services, many community banks find themselves at a significant inflection point where traditional growth strategies like building or acquiring an expansive, and often expensive, branch network are being reexamined.

In this session, we examined how banks can utilize a hybrid approach and co-opt, partner with or acquire FinTech companies, wealth management and trust operations and insurance brokerages. By pairing traditional banking services with other financial services and means of delivery, banks can obtain more touch points for customer relationships, enhance revenue and ultimately improve the bank’s valuation.

Andrew K. Gibbs, CFA, CPA/ABV, Senior Vice President, and Jay D. Wilson, CFA, ASA, CBA,Vice President, alongside Chris Nichols, Chief Strategy Officer at CenterState Banks, Inc. presented at Bank Director’s 2017 Acquire or Be Acquired Conference on January 30, 2017.

Creating Strategic Value Through Financial Technology

FinTech is not solely a threat to community banks—it’s an opportunity. Through successfully leveraging FinTech, community banks can level the playing field with larger banks and non-bank lenders, as they improve their profitability, performance, customer satisfaction, and value. Creating Strategic Value Through Financial Technology shows you how. The book contains 13 chapters broken into three sections:

- Section I introduces FinTech, examines its history and outlook, and also discusses key reasons that FinTech can have a significant positive impact on community banks in the U.S.

- Section II provides an overview of important trends and FinTech companies in prominent FinTech niches, such as bank technology, alternative (i.e., online) lending, payments (including blockchain technology), wealth management, and insurance. This section is helpful for community bankers interested in understanding more about particular FinTech niches.

- Section III presents a range of topics important to community bankers as they assess potential FinTech niches, partnerships, and acquisitions. Highlights include an examination of how to approach the build, buy, or partner decision when considering a FinTech niche or company; key return metrics to compare FinTech strategies to traditional strategies; and how community banks can value and structure potential partnerships, acquisitions, and investments in FinTech companies.

Creating Strategic Value through Financial Technology illustrates the potential benefits of FinTech to banks, both large and small, so that they can gain a better understanding of FinTech and how it can be leveraged to enhance profitability and create value for shareholders.

Order your copy today via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, or Wiley in hardcover or as an ebook.

EBITDA Single-Period Income Capitalization for Business Valuation

[Fall 2016] This article begins with a discussion of EBITDA, or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. The focus on the EBITDA of private companies is almost ubiquitous among business appraisers, business owners, and other market participants. The article then addresses the relationship between depreciation (and

amortization) and EBIT, or earnings before interest and taxes, as one measure of relative capital intensity. This relationship, which is termed the EBITDA Depreciation Factor, is then used to convert debt-free pretax (i.e., EBIT) multiples into corresponding multiples of EBITDA. The article presents analysis that illustrates why, in valuation terms (i.e., expected risk, growth, and capital intensity), the so-called pervasive rules of thumb suggesting that many companies are worth 4.03to 6.03EBITDA, plus or minus, exhibit such stickiness. The article suggests a technique based on the adjusted capital

asset pricing model whereby business appraisers and market participants can independently develop EBITDA multiples under the income approach to valuation. Finally, the article presents private and public company market evidence regarding the EBITDA Depreciation Factor, which should facilitate further investigation and analysis.

[Reprinted from the American Society of Appraisers Business Valuation Review, Volume 35, Issue 3, Fall 2016]

Download the article in pdf format here.

Are Robo-Advisors on Any Banker’s Wish List?

Christmas appears to have come early for some bankers and their investors with the SNL Bank index up over 30% from the November 8, 2016 election to mid-December. While optimism abounds, one inconvenient truth remains for the time being: ROEs for the banking industry as a whole remain below pre-financial crisis levels despite credit costs that are below most historical standards. The factors challenging ROEs for the sector are numerous but include: compressed net interest margins from a historically low rate environment, enhanced competition from non-banks, a challenging regulatory and compliance environment, and evolving consumer preferences regarding the delivery of financial services.

These factors are particularly acute for most community banks that depend heavily on spread income and do not have the scale to absorb expense pressures as easily as their larger brethren. Further, many community banks are at a crossroad because their ROE consistently has fallen below the cost of capital, which in turn is forcing boards to consider strategic options like outright sales or potentially risky acquisition strategies to obtain scale.

In an ideal world, community banks could easily add fee businesses that are capital-light, such as wealth management and trust operations, to boost returns. By pairing traditional banking services with other financial services like wealth management, banks can obtain more touch points for customer relationships, enhance revenue, and potentially improve the bank’s valuation. While we have previously spoken about the potential benefits to community banks of acquiring or building out a traditional wealth management operation, we have not addressed emerging FinTech companies, like robo-advisors, that are focused on the wealth management space.

While there has been a race to partner and/or acquire robo-advisors by many of the larger asset managers and banks, there have also been some interesting partnerships with community banks. One such partnership struck is among Cambridge Savings Bank, a $3.5 billion bank located near Boston, and SigFig, a robo-advisor founded in 2007. While SigFig has relationships with UBS and Wells Fargo, its partnership with Cambridge Savings is notable because the two built a service called “ConnectInvest.“ When announced in the spring of 2016, the partnership was described as the “first automated investment service integrated and bundled directly into a retail bank’s product offerings in the U.S.” ConnectInvest, which is available to Cambridge’s customers digitally (mobile and website), “allows customers to easily open, fund, and manage an automated investment account tailored to their goals.” Cambridge’s customers are interested in the offering and have started using it. The goal is get up to 10% of its customer base using ConnectInvest.

With this example in mind, the remainder of this article offers an overview of the robo-advisory space for our community bank readers so that they may gain a better understanding of the key players and their service offerings and assess whether their bank could benefit from leveraging opportunities in this area.

An Overview of Robo-Advisors

Robo-advisors were noted by the CFA Institute as the FinTech innovation most likely to have the greatest impact on the financial services industry in the short-term (one year) and medium-term (five years). Robo-advisory has gained traction in the past several years as a niche within the FinTech industry by offering online wealth management tools powered by sophisticated algorithms that can help investors manage their portfolios at very low costs and with minimal need for human contact or advice. Technological advances that make the business model possible, coupled with a loss of consumer trust in the wealth management industry in the wake of the financial crisis, have created a favorable environment for robo-advisory startups to disrupt financial advisories, RIAs, and wealth managers. This growth is forcing traditional incumbents to confront the new entrants by adding the service via acquisition or partnership rather than dismiss it as a passing fad.

Robo-advisors have been successful for a number of reasons, though like many digital products low-cost, convenience, and transparency are common attributes.

- Low Cost. Automated, algorithm-driven decision-making greatly lowers the cost of financial advice and portfolio management.

- Accessible. As a result of the lowered cost of financial advice, advanced investment strategies are more accessible to a wider customer base.

- Personalized Strategies. Sophisticated algorithms and computer systems create personalized investment strategies that are highly tailored to the specific needs of individual investors.

- Transparent. Through online platforms and mobile apps, clients are able to view information about their portfolios and enjoy visibility in regard to the way their money is being managed.

- Convenient. Portfolio information and management becomes available on-demand through online platforms and mobile apps.

Consistent with the rise in consumer demand for robo-advisory, investor interest has grown steadily. While robo-advisory has not drawn the levels of investment seen in other niches (such as online lending platforms), venture capital funding of robo-advisories has skyrocketed from almost non-existent levels ten years ago to hundreds of millions of dollars invested annually the last few years. 2016 saw several notable rounds of investment into not only some of the industry’s largest and most mature players (including rounds of $100 million for Betterment and $75 million for Personal Capital), but also for innovative startups just getting off the ground (such as SigFig and Vestmark).

The table below provides an overview of the fee schedules, assets under management and account opening minimums for several of the larger robo-advisors. The robo-advisors are separated into three tiers. Tier I consists of early robo-advisory firms who have positioned themselves at the top of the industry. Tier II consists of more recent robo-advisory startups that are experiencing rapid growth and are ripe for partnership. Tier III consists of robo-advisory services of traditional players who have decided to build and run their own technology in-house.

As shown, account opening sizes and fee schedules are lower than many traditional wealth management firms. The strategic challenge for a number of the FinTech startups in Tiers I and II is generating enough AUM and scale to produce revenue sufficient to maintain the significantly lower fee schedules. This can be challenging since the cost to acquire a new customer can be significant and each of these startups has required significant venture capital funding to develop. For example, each of these companies has raised over $100 million of venture capital funding since inception.

Key Potential Effects of Robo-Advisory

We see five potential effects of robo-advisors entering the financial services landscape.

- Fee pressure. Robo-advisors may be a niche area for the time being, but the emergence and success of a technology-driven solution that challenges an age-old business (wealth management) epitomizes what has long been associated with internet (and digital) delivery of services: faster, better, and cheaper.

- The Democratization of Wealth Management. As a result of the low costs of robo-advisory services, new investors have been able to gain access to sophisticated investment strategies that, in the past, have only been available to high net worth, accredited investors.