Dividend Recaps Can Unlock Value

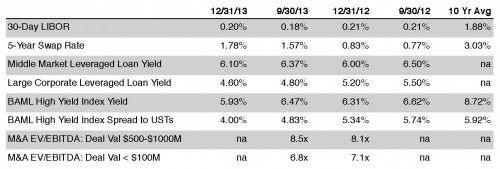

When announcing its decision to initiate the taper process with a reduction of $10 billion in monthly bond purchases on December 18, 2013, the Federal Reserve emphasized “forward guidance” that the fed funds target rate will remain unchanged at 0% to 0.25% for an extended period. As a result, capital markets may remain well bid with below average volatility and credit spreads that remain relatively tight in a very low rate environment.

One permutation of the Fed’s policy is that adding leverage to corporate balance sheets is inexpensive even though the ethos post-crisis is de-leveraging among consumers and corporations. It is especially inexpensive if borrowing is obtained via a bank revolver with a multi-year commitment and 30-day LIBOR as the base rate. According to Thomson Reuters, leveraged loan issuance (debt > 4.0x EBITDA) was $1.14 trillion in 2013, up from $664 billion in 2012. About two-thirds of the issuances were attributable to refinancing activity vs. one-third of “new money” issuances.

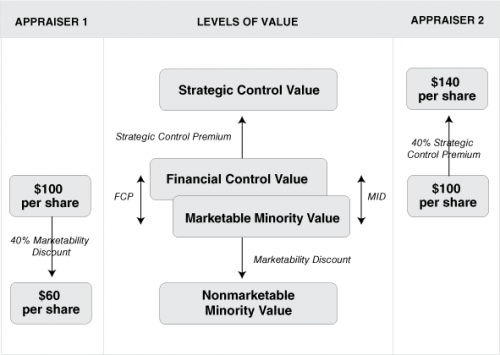

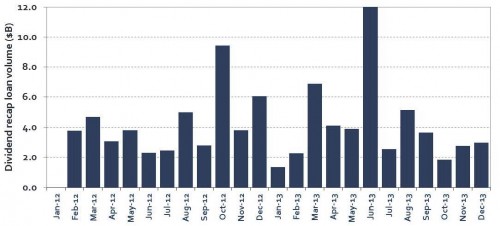

Private equity investors have taken note and have been the primary force behind an increase in dividend recaps that gained traction in 2012 as firms borrowed from banks and the corporate bond market to fund large distributions. As shown in Figure 1, the trend has continued in 2013, though it has slowed the past few months. Dividend recapitalizations totaled $50 billion in 2013 compared to $47 billion in the 2012. It may be that the pick-up in IPOs and perhaps a hoped for increase in M&A by private equity investors has led to a little bit lower dividend recap activity lately.

Figure 1

Dividend recaps can be an attractive transaction for a board to undertake to unlock value, especially since multiples for many industries have recovered to pre-crisis levels while borrowing rates are very low and most banks are anxious to lend. In addition, dividend recaps allow privately held businesses to convert “paper” wealth to liquid wealth and thereby facilitate diversification.

Dividend recaps raise solvency and possibly fairness issues if an alternative transaction was under consideration. In a future edition of the Transaction Advisor we will take a look at solvency specific issues. Nevertheless, given the implications of a recap transaction a financial advisor’s views should be solicited as part of a board’s duty to its shareholders to make an informed decision.

Figure 2

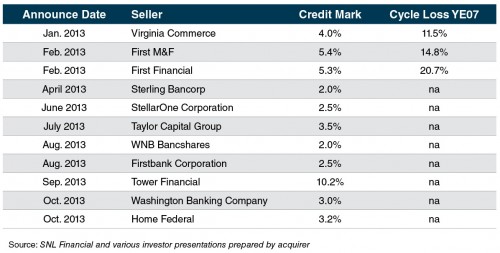

Credit Marks on Acquired Loan Portfolios Trend Down During 2013

Merger related accounting issues for bank acquirers are often complex. In recent years, the credit mark on the acquired loan portfolio has often been cited as an impediment to M&A activity as this mark can be the most critical component that determines whether the pro-forma capital ratios are adequate. As economic conditions have improved in 2013, bank M&A activity has also picked up and we thought it would be useful to take a look at the estimated credit marks for some of the larger deals announced in 2013 (i.e., where the acquirer was publicly traded and the reported deal values were greater than $100 million) to see if any trends emerged.

As detailed below, the estimated credit marks declined during 2013 with only one deal reporting a credit mark larger than 4% after the first quarter of 2013 compared to all deals being in excess of 4% in the first quarter of 2013. The reported estimated credit marks for 2013 were also generally below those reported in larger deals in 2010, 2011, and 2012 when the estimated credit marks were often in excess of 5%.

This trend reflects a number of factors including most notably:

- Improved economic trends. Economic data from the Federal Reserve of St. Louis indicates that real GDP was up 1.9% through the first nine months of 2013 while the unemployment rate was down to 7.0% in November 2013 compared to 7.9% in January M2013.

- Higher real estate values. For perspective, the 10- and 20-city composites of the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price indices increased 10.3% and 13.3% through September 30, 2013 (per SNL Financial). Additionally, economic data from the Federal Reserve of St. Louis indicated that commercial real estate prices in the U.S. were up 10.6% over the 12 months ended June 30, 2013.

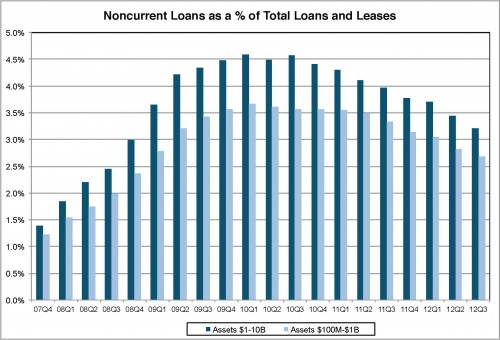

- Reduced levels of noncurrent loans. As detailed below, credit migration continued to be positive throughout 2013 and levels have declined to almost pre-financial crisis levels (third quarter 2013 levels approximated levels last observed in the fourth quarter of 2008).

Mercer Capital has provided a number of valuations for potential acquirers to assist with ascertaining the value and estimated credit mark of the acquired loan portfolio. In addition to loan portfolio valuation services, we also provide acquirers with valuations of other financial assets and liabilities acquired in a bank transaction, including depositor intangible assets, time deposits, and trust preferred securities.

Feel free to give us a call to discuss any valuation issues in confidence as you plan for a potential acquisition.

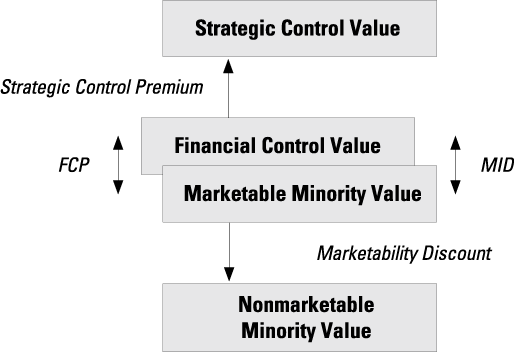

Valuation Strategies for Dealing with the IRS

Business owners seldom think about a valuation strategy for dealing with the IRS on gift and estate tax matters. Many owners ignore the importance of estate tax planning, which can also be called lifetime planning. Lack of vision or short-sightedness on planning can be damaging to family wealth and succession.

Things to Consider

There is a demographic bubble involving ownership of closely held business interests held by baby boomers. This will bring a huge amount of wealth into the estate tax pipeline over the next two decades. Business owners should contemplate three things:

- The IRS is aware of the potential revenue from this demographic bubble.

- If a business owner engages in the gifting of closely held stock during his/her lifetime, the need for an “IRS strategy” will be important.

- The need for an “IRS strategy” will be critical for executors and heirs at the time of death.

The old strategy goes like this: “Let’s try to value things as low as possible and with as little documentation as possible, thereby saving money. If questions are raised, we’ll try to negotiate a reasonable settlement.”

IRS Strategy

This strategy often results in loggerhead positions that lead to protracted negotiations, Tax Court, or unreasonable settlements. At the very least, dealing with the IRS in this fashion is quite disruptive to families and businesses. A different strategy seems more appropriate in today’s environment. Recognize first that if you own a successful closely held business, you, your heirs, and/or your advisors will be dealing with the IRS regarding estate tax matters. Therefore, your “IRS strategy” might be composed of the following:

- Obtaining a business valuation from a qualified independent appraiser as the basis for making substantial gifts, or for estate tax returns. Court cases have cited the importance of specific business valuation experience, credentials and training in the court’s evaluation of the credibility of expert witnesses.

- Insuring that your business appraiser prepares a well-written, fully documented valuation report that explains the rationale for important valuation assumptions, or for the use of valuation premiums or discounts.

- Submitting the valuation report as an attachment to the gift or estate tax return. By doing so, you will increase the probability that your gift or estate tax matter is settled timely and fairly.

If your business appraiser’s valuation report is well-supported and reasonable in its conclusion, you have little reason to negotiate with the IRS until credible evidence calling for a different conclusion is provided. An estate tax return for a substantial estate which is submitted without a supporting appraisal is an invitation for the IRS to negotiate for higher taxes.

Absent the business valuation, you will have little basis to argue your original position. If you and the IRS reach an impasse and both sides then are required to obtain an appraisal, your appraiser’s independence can be called in question, particularly if the conclusion is supportive of your original position. If the conclusion is not supportive, you have an entirely different set of problems. Further, rest assured that valuations prepared under the threat of immediate litigation tend to be more expensive than those prepared in the ordinary course of business. Finally, know with certainty that the negotiation process with the IRS is costly in terms of business time, personal time, and mental energy, not to mention valuation, legal, and accounting fees.

Remember the old adage, “It is always better to do things right the first time.” Add to that, “It is always more expensive in terms of time, energy, and resources to fix what could have been done right the first time.”

Conclusion

If you own a business or serve as a professional advisor to business owners, engage a competent business appraiser when the need arises. Mercer Capital is one of the largest and most respected business valuation firms in the nation. Give us a call at 901.685.2120 to discuss your valuation issues in confidence.

8 More Mistakes To Avoid in Valuations: According to Tax Court Decisions

In this second part of a two-part series, we have collected eight examples of mistakes that valuation experts have made, as reported in federal courts tax decisions (see Value MattersTM, Issues No. 4, 2013 for “16 Mistakes to Avoid in Valuations: According to the Tax Court.”) It is important to note that there are two sides to every story, and courts do not always get it right. For this reason, we do not name any valuators in this collection of mistakes to avoid.

1. Insufficient Due Diligence

In Freeman Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1996-372), the taxpayer’s valuator failed to ask the subject company’s president whether he had plans for an IPO. In the Tax Court’s opinion:

The corporation had an initial public offering of stock in June 1990, at a price of $10 per share. The possibility of an initial public offering was discussed at a meeting of the board of directors of the corporation on August 24, 1989. In his report, [the valuator] states specifically that (1) during his interview with Bernard V. Vonderschmitt, president … he did not inquire as to whether, on October 22, 1989, the corporation had any plans for a public offering of stock, and (2) he did not consider the potential for a public offering in carrying out his valuation assignment.

Petitioner has cited to us no authority prohibiting an inquiry into plans for a public offering. We assume that a potential purchaser would be interested in such plans and might pay a premium depending on her judgment of the likelihood of such an offering.

Likewise, in Bennett Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1993-34), the Tax Court criticized a valuator for failing to investigate as would a hypothetical willing buyer:

Compounding this shortcoming is [the valuator’s] exclusive reliance upon the numbers listed on Fairlawn’s balance sheets with no further investigation or due diligence. [The valuator] himself acknowledged at trial that a hypothetical willing buyer would look behind the balance sheet numbers in evaluating their correctness and in applying valuation methods. Although [the appraiser] stated that he was not able to obtain requested documents from Fairlawn, we feel that [he] did not perform sufficient due diligence in this matter.

It is imperative that the valuator document all due diligence efforts in the valuation report, because the valuator may not get a chance to do so on the witness stand. Include unsuccessful efforts to obtain important information, with a legitimate explanation of why the effort failed (See, e.g., Winkler Estate v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 1989-231).

Another example of lack of due diligence, as well as incorrectly written descriptive report, is where the valuator failed to make relevant inquiries in Ansan Tool and Manufacturing Co. v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1992-121).

[The valuator] had not discussed Mario Anesi’s departure from petitioner with management to determine whether customers would leave or stay with petitioner. It is also unclear how [he] determined that only 10 percent of sales would be lost if Mario Anesi competed against petitioner, nor why the 10 percent loss would be limited solely to the first year after he left petitioner.

2. Unforeseeable Subsequent Events

A dilemma inherent in retrospective valuations is that life and business carry on after the valuation date. Consequently, the post-valuation-date events and cycles become known to valuators during the valuation process. The uncertainties, economic or otherwise, that exist on the valuation date can be lost when subsequent reality becomes visible and measurable. The problem that occurs when future expectations blend into history is that events subsequent to the valuation date are not supposed to be considered in a valuation, except to the extent that such events and conditions could have been knowable or reasonably foreseen.

A valuator’s observations and perspective could potentially be influenced by subsequent events. This can be equally true of the information and feedback provided by the various stakeholders to a valuation event. The question often becomes whether that information was knowable as of the valuation date. Love Estate. v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1989-470) is instructive on this issue:

… after Mrs. Love’s death, Praise was determined to be in foal. Surely, this increased her value considerably. Respondent’s expert assumed for the purpose of his valuation that Praise was pregnant at the date of Mrs. Love’s death, although it was impossible to ascertain pregnancy on that date. A hypothetical willing buyer would not have been aware that Praise was in foal. The report of respondent’s expert, therefore, contravenes the regulations by making use of hindsight.

A tax valuation is made as of a certain date; for example, date of death or date of a gift. Generally, a valuator should only consider circumstances in existence on the valuation date and events occurring up to that date. The courts, however, have allowed evidence of subsequent events if those events were reasonably foreseeable as of the valuation date (Spruill Estate v. Commissioner, 88 T.C. 1197 (1987)).

3. Improper Reliance on a Draft Valuation Report

Valuators sometimes have to rely on the work of other valuators whose work may be in progress at the same time. In Cloutier Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1996-49), a valuator lost credibility for failing to follow up on a work-in-process:

[O]ne of the appraisals on which [the valuator] purported to rely was merely a draft of an appraisal, and [the valuator] never spoke to the author concerning the author’s completion of that draft or about any of the information contained therein.

4. Ignoring Asset Appraisals in Other Disciplines

In Ford Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1993-580), the taxpayer’s expert used historic book value of assets in the net value approach, even though asset appraisals had been obtained and were available. The Tax Court said:

[P]etitioner’s expert valued the assets of each company using unadjusted book value, thereby undervaluing the assets themselves. Petitioner’s expert generally used historic book value as a factor in his formula, notwithstanding that petitioner had obtained appraisals as of the valuation date for certain of the Ford companies’ assets, namely, the real estate owned by Ford Mercantile and Ford Dodge, the securities issued by unrelated entities that were owned by Ford Mercantile, Ford Dodge, Ford Real Estate, and Ford Moving, as well as the cars, trucks, trailers, and securities issued by unrelated entities that were owned by Ford Van.

5. Use of Data with Caveats or Warnings

In Haffner’s Service Station, Inc. v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2002-38), a valuator used data that was subject to an explicit warning by the publisher of the data:

[The valuator] acknowledged at trial that the general data was unreliable, he stated specifically that he knew that Robert Morris’s publication warns readers explicitly that the data is not statistically accurate and should not be relied upon or used in a legal proceeding. [The valuator] attempted to rationalize his reliance on the Robert Morris compilation by stating: “Unfortunately, I had to use what was available. It was … the best stuff around. I have to concede that they’re flawed.” We find this attempt unavailing.

6. Using an Ancient Comparable Sale

The market approach is premised on the use of sales that occur reasonably close to the valuation date. In Hagerman Estate v. United States (81 AFTR2nd Par. 98-771(C.D. III. 1998), the court pointed out:

He relied particularly on Sale 2 finding the subject farm was of the same value. Unfortunately for Plaintiffs, the sale price for Sale 2 was as previously indicated 20 years outdated. Clearly, [the valuator’s] valuation of Farm 4 is seriously flawed.

7. Neglecting to Identify an SIC

In Jann Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1990-333), a valuator referred to a Standard Industrial Code in his report, but failed to identify what category that number referred to:

[The valuator’s] report referred to comparable companies but did not identify them; did not state whether [he] used average earnings or a weighted average earnings in his analysis; referred to a standard industrial classification number but did not identify it; and did not explain how he arrived the price-earnings ratio of 9.8.

8. Failure to Proofread

The last mistake on this list, fittingly, is from Hinz Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2000-6), in which the valuator apparently neglected to proofread his report, and the Tax Court socked it to him: When asked why his expert witness report relies on a statute that had been repealed years earlier, [the valuator] replied as follows:

“I think this is boilerplate that was put in by my secretary over the last–ever since 1992, and I have never taken it out.” Also, in some instances, the textual descriptions of properties in [the valuator’s] written report did not match the properties listed in the accompanying matrix. It was as though [the valuator] had revised parts of a draft of his report but inadvertently kept parts of former drafts that no longer fit the revised draft.

Conclusion

In this article, we presented eight mistakes made by valuation experts, as reported in federal courts in tax decisions. Just because one judge in one case calls something a mistake doesn’t make it a mistake in all cases. But we think the above examples are indeed instructive in most valuation situations.

L. Paul Hood, Jr., Esq.

The University of Toledo Foundation

paul@acadiacom.net

Timothy R. Lee, ASA

Mercer Capital

leet@mercercapital.com

Note: This article originally appeared in the September/October 2013 issue of The Value Examiner. It was adapted from Chapters 17-18 of A Reviewer’s Handbook to Business Valuation by L. Paul Hood, Jr., and Timothy R. Lee, (John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2011). For book details, see www.mercercapital.com or http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-0470603402.html.

Share Repurchases

This article has been adapted from the post “Bill Gross, Carl Ichan and Share Repurchases,” which originally appeared November 7, 2013 in the “Nashville Notes” blog on SNL.com. Republished with permission.

Many bank analysts have been arguing that investors should buy bank stocks because capital is building faster than it can be deployed. The Federal Reserve, unlike during the pre-crisis era, is governing the amount of capital returned to shareholders. Basel III is another governor, especially given the enhanced leverage ratio requirement large U.S. banks are facing.

But are buybacks a good idea for bank managers today? I question the wisdom of many of the repurchases that are occurring when bank stocks are trading at price-to-earnings ratios in the mid-teens and at 1.5x to 2.0x price to tangible book value. The bane of buybacks, and M&A for that matter, is the human propensity to engage in risky behavior at the top of the market when all is well and risks seem minimal.

Share buybacks are not high finance. They use excess capital or cheap debt to fund the repurchase of shares. From a flow-of-funds perspective, repurchases also support share price — especially for small-cap banks that are thinly traded. Nevertheless, I do not think it is simply a constant P/E ratio and higher EPS from a reduced share count that yields a higher stock price. Value matters as well for repurchases.

Ideally buybacks will occur when a stock is depressed, not when it is pressing a 52-week or multiyear high because the Fed has had the monetary spigots wide open for five years. The majority of publicly traded banks today are producing a return on tangible common equity in the range of 9% to 15%. If the shares are trading at 1.5x to 2.0x tangible book value, the effective return for new money is about 6% to 8% (based on the return on tangible equity divided by the price-to-tangible book value multiple) if the bank can reinvest retained earnings at a comparable return on tangible equity. Of course, returns could increase, but that seems doubtful to me when the mortgage refinancing boom is over, loan yields are grinding lower, and credit costs for many banks are low.

Banks that repurchased shares in 2012 have seen varied results. It may be that banks producing the lowest returns, such as First Horizon National Corp., acquired shares in 2012 at a bargain price compared to banks that trade at higher multiples, such as Bank of Hawaii Corp.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. is an unanswered question too. Repurchases made in 2012 may prove to be money well spent provided it is not going to be needed to shore up capital for litigation-related losses. JPMorgan’s 2012 repurchases occurred at an average price of $42.19 per share, which was a modest premium to tangible book value. Today, the shares trade around $52, even though the company’s outlook may be cloudier than it was in 2008.

CapitalSource Inc., Huntington Bancshares Inc., Fifth Third Bancorp and KeyCorp appear to have spent excess capital well in 2012 given a combination of low valuations and adjusted returns in the low teens. The home run among the group is CapitalSource, which repurchased 17.2% of its year-end 2011 shares during 2012 for an average price of $6.91 per share and has bought back 7.0% of its year-end 2012 shares during 2013 for an average price of $9.14 per share. The company subsequently agreed to be acquired by PacWest Bancorp on July 22. Its share price was $13.11 at the closing bell Nov. 4.

Having capital and the willpower not to repurchase requires discipline. It is also a tacit admission by the management team that the company’s shares may be over-valued.

So what is the alternative in the context of capital, profitability, and growth “in that order,” as ex-Whitney Holding Corp. CEO Bill Marks used to say?

One option is to sit on capital waiting for the inevitable cyclical downturn, though that may be a long wait given the lack of loan growth and Fed actions that are indirectly supporting credit quality.

A second option is to do acquisitions using excess capital and richly-valued shares.

A third option is to return capital via special dividends. However, Wall Street has never been as excited about special dividends compared to buybacks because they are one-time events with no impact on EPS or market demand.

If the Fed manages to engineer further appreciation in asset prices, including bank stocks, the sector may see more boards electing to use special dividends to return capital — provided the Fed is agreeable.

Mercer Capital has three decades of experience of advising banks, non-depository financial institutions and corporations in matters related to share repurchases, capital planning and valuation for a variety of purposes. Whether considering an acquisition, a sale, or simply planning for future growth, Mercer Capital can help financial institution accomplish their objectives through informed decision making.

Community Bank Stress Testing: A Hypothetical Example

For more information on this topic, please see “Community Bank Stress Testing.”

The following article provides an illustrative example of the primary steps to construct a “top-down” portfolio-level stress test.

Determine the Economic Scenarios to Consider

While this step will vary depending upon a variety of factors, one way to determine your bank’s economic scenario could be to look to utilize the supervisory scenarios announced (in November 2012) by the Federal Reserve for the stress tests of the largest financial institutions in the U.S. While the more global economic conditions detailed in the supervisory scenarios may not be applicable to community banks, certain detail within the scenarios presented could be useful when determining the economic scenarios to model at your bank. Consider the following U.S. economic conditions included in the scenarios presented by the Federal Reserve:

- Supervisory Adverse Scenario. Includes a moderate recession in the U.S. beginning in late 2012 and lasting until early 2014, including further weakening in housing (a decline of 6% in house prices during 2013), a decline in equity prices of approximately 25% in 2013, and the unemployment rate rising to above 9% in early 2013 and reaching 10% by mid-2015.

- Supervisory Severely Adverse Scenario. Includes a substantial weakening in economic activity, including further weakening in housing (a decline of more than 20% in house prices by 2014), a decline in equity prices of more than 50%, and the unemployment rate reaching 12% by mid-2014.

Based upon these scenarios, one might then decide to consider applying the following two scenarios within your community bank’s stress test:

- Community Bank Adverse Scenario. Includes a moderate recession in the U.S. and moderately weak economic conditions within the local communities served by the bank, which will include a decline in collateral values (notably housing and CRE of roughly 5-10%) and a rise in the unemployment rate to over 9%; and,

- Community Bank Severely Adverse Scenario. Includes a strong recession for both the U.S. and very weak economic conditions within the local communities served by the bank, which will include a decline in collateral values (notably housing and CRE of more than 20%) and the unemployment rate reaching 12.0%.

Segment the Loan Portfolio

This step entails segmenting the loan portfolio into smaller groups of loans with similar loss characteristics. One way cited in the OCC guidance is to segment the loans through Call Report categories in Schedule RC-C (such as construction and development, agricultural, commercial real estate, etc.). Additional segmentation may be needed beyond Call Report categories to address other key elements such as risk grade, collateral type, lien position, loan subtype, concentration risk and/or the vintage of the loan portfolio (i.e., loans primarily originated pre- or post-financial crisis). Other assets that could decline significantly in value, such as the investment portfolio and/or other real estate owned, may also need to be considered. Further, certain loans (or segments of loans) such as larger, higher risk grade loans may need to be segregated as they lend themselves to a more “bottom up” type of analysis (i.e., evaluated individually to determine their likely loss rate in a stress environment).

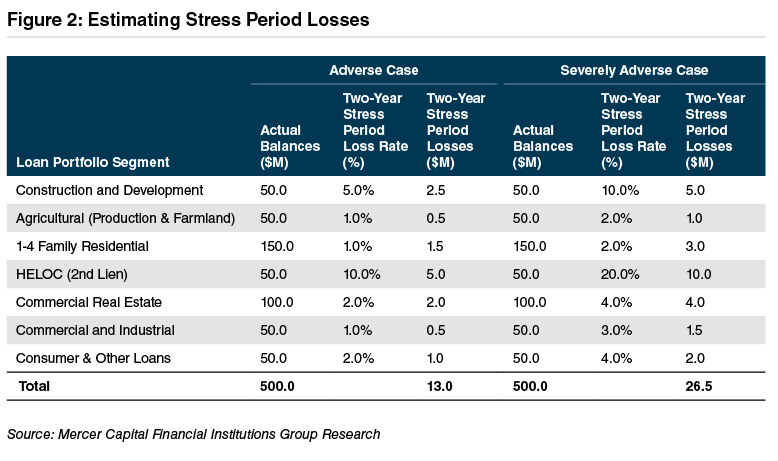

Estimate Loan Portfolio Stress Losses

Once the assets have been segmented appropriately, the next step involves estimating the potential loan losses over a two-year stress test horizon (or potentially longer) for the entire loan portfolio. In order to estimate the losses, the OCC guidance suggests using the bank’s historical default and loss experience during prior recessions or financial stress periods as a starting point. Beyond that, the bank may also look to outside references for ranges of loss rates for community banks during stress periods and/or certain other peer average loss rates during financial stress periods.

Let’s assume that the subject bank is headquartered in Chicago, has $500 million in loans, and has experienced historical loss rates moderately in line with its peers (one comprised of banks located in the same geographic area and the other consisting of banks located throughout the U.S.). To estimate the appropriate loss rates during the stress periods, one might then consider annual charge-off rates as a percentage of average loans of the two peer groups for each loan portfolio segment (Construction & Development segment shown below).

- Severely Adverse Scenario. To estimate stress period losses under the severely adverse scenarios, one might rely primarily on the peer group losses observed from 2009 through 2011. For perspective, the unemployment rate in the Chicago MSA was 11.8% in January of 2010 and above 10% from May 2009 through August 2010. The S&P Case Sheller Home Price Index for the Chicago MSA was 125.11 in January of 2010, down 25.8% since peaking in September of 2006.

- Adverse Scenario. To estimate losses under the adverse scenario, one could focus on periods when economic conditions were still relatively weak but improved from the depth of the financial crisis and consider the charge-off levels observed in 2008 and 2012. A similar process could then be repeated for other loan portfolio segments to derive the appropriate two-year stressed loss rates.

The following table details a hypothetical example of estimating loan portfolio stress period losses (loss rates shown for the C&D portfolio are based on Figure 1 while loss rates for the other segments are for illustrative purposes only).

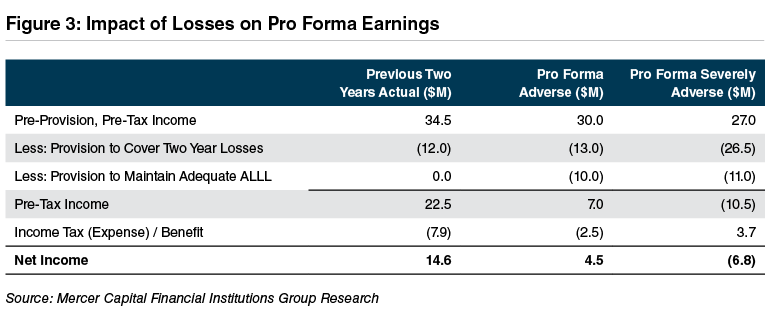

Estimate the Impact of Stress on Earnings

Now that the loan portfolio losses have been determined, the next step entails estimating the potential impact on net income from the scenario(s) analyzed previously. Estimating pre-provision, pre-tax income in the different scenarios can be tricky as the impact of higher non-performing assets on revenue (i.e., nonaccrual loans) and expenses (i.e., collection costs) should be considered. Further, the impact on liquidity (i.e., funding costs) and interest rate risk (i.e., net interest margin) should also be considered.

Once pre-provision, pre-tax income has been determined the next step entails estimating the appropriate provision over the stressed period. The provision can be broken into two components: the provision necessary to cover losses estimated in Figure 2 and the portion of provision necessary to maintain an adequate allowance for loan losses (ALLL) at the end of the two-year period. When determining the portion of provision necessary to maintain an adequate ALLL at the end of the stress period, management should consider that stressed environments may increase the need for a higher ALLL. Finally, the income tax expense/benefit arising from the estimate of pre-tax income should be applied.

The following table details an example of this step.

Other key considerations here might include: How will loan migrations in the different scenarios impact pre-provision net income? How might the economic scenarios forecast impact pre-provision net income? How will the elevated level of losses over the stress periods impact the provision necessary to maintain an adequate ALLL? How will the losses impact the bank’s tax expense/benefit?

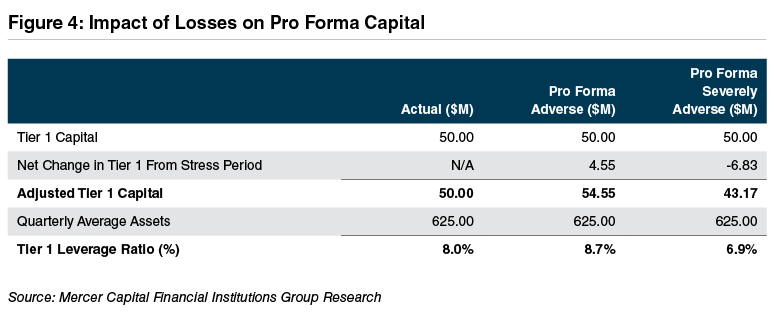

Estimate the Impact of Stress on Capital

This step entails estimating the bank’s capital ratios at the end of the stressed period. To accomplish this, the estimated changes in equity, Tier 1capital, average assets, and risk-weighted assets during the stressed period should be considered.

The following table details an example of this step.

Other key considerations here might include: What are the potential impacts on capital and risk-weighted assets from Basel III? What is the projected balance sheet growth/contraction over the stressed period?

Loan Growth Resumes, But Remains Slow

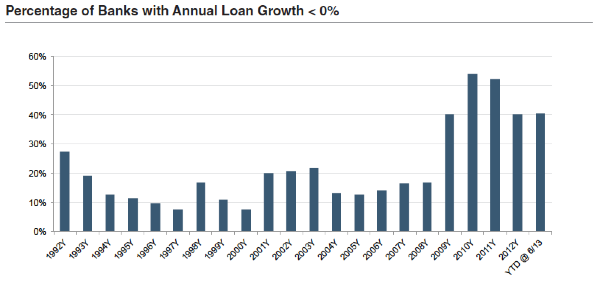

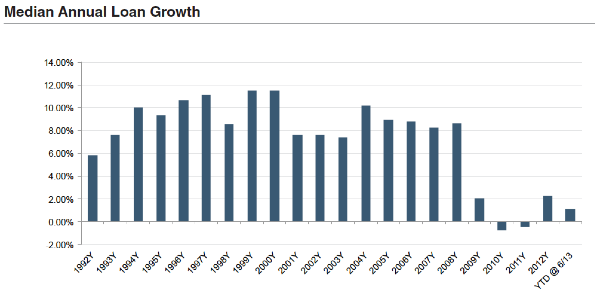

Loan growth continues to remain a struggle for community banks as loan demand remains weak in most regions. Based on Call Report data as of June 30, 2013 for approximately 3,750 banks with assets between $100 million and $5 billion, more than 50% of banks reported lower loan balances in 2010 and 2011. In 2012 and year-to-date in 2013, approximately 40% of banks have reported lower loan balances.

Community banks as a group reported negative median loan growth in 2010 and 2011. Beginning in 2012, loan growth resumed, with the community bank group examined realizing median growth of 2.2%. Year-to-date through June 2013, median growth was 1.1%, or 2.2% annualized, on pace with the 2012 growth figure. The low level of growth in loan portfolios is well below the historical average, including prior recessions. During the 2001-2002 recession, for example, median loan growth was approximately 7.5% for the community bank sample.

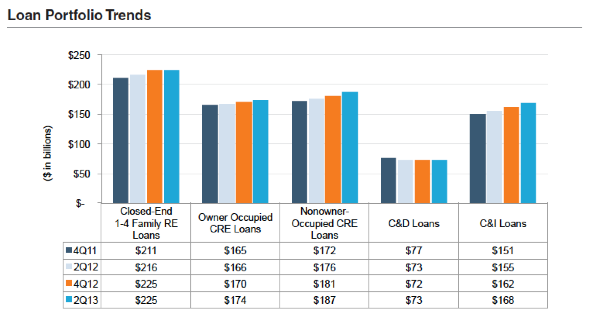

The modest loan growth realized in 2012 and year-to-date in 2013 has been spread across portfolio sectors, with all non-agricultural loan categories up 6.8% at June 30, 2013 from year-end 2011. Within the non-ag categories, 1-4 family mortgages were up 6.4%, CRE loans were up 7.4% with most of the increase in nonowner-occupied CRE loans, and commercial/industrial loans were up 11.3%. Construction and development credits were the only sector that saw declines in the last 18 months, with total C&D loans down 4.9% from year-end 2011.

An analysis of mortgage data by SNL Financial indicates that residential loan growth has been consistent across the country, with 932 of the 955 metro areas with available data reporting increases in originations.1 The analysis by SNL looks at comprehensive data filed by lenders pursuant to the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act for the 2012 fiscal year. The analysis shows the largest increases in mortgage lending activity in the areas that were hardest-hit by the recession, including Orlando, Phoenix, Las Vegas, Detroit, and Sacramento, which all posted growth in mortgage lending over 75% in 2012. Overall, funded mortgage loan volume was up 43% from 2011, increasing from $1.5 trillion to $2.1 trillion for the metro areas included in the data set.

For the community bank sample, total growth in single-family mortgages was slower than the aggregate mortgage data for all institutions, with loan volume up 6.5% for the 2012 fiscal year, indicating that the majority of loan growth, at least in the residential mortgage sector, was led by larger institutions.

Endnotes

1 “Loan Growth Spanned Entire US in 2012,” by Sam Carr and Fox, Zach. Published by SNL Financial, October 3, 2013.

16 Mistakes to Avoid in Valuations: According to Tax Court Decisions

Business valuation textbooks, training manuals, and conference presentations may do a good job of teaching the right ways to conduct valuations. But in some respects the most authoritative teacher of what is right and, just as importantly, what is wrong is the decision of the court in a dispute over the value of a privately held business or shares thereof.

In this article we have collected 16 examples of mistakes made by valuation experts, as reported in federal courts in tax decisions. It is important to note that there are two sides to every story, and courts do not always get it right. For this reason, we do not name any valuators in this collection of mistakes to avoid.

1. Lacking Explanation Needed to Replicate

No matter how “correct” your conclusion of value is, the court may not accept it if you do not provide sufficient details and explanations about how you arrived at that conclusion. Another valuator should be able to replicate your work after reviewing your report or work-papers. In Winkler Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1989-231. See also Former IBA Business Appraisal Standards Sec. 1.8. See also True Est. v. Comr., T.C. Memo 2001-167, aff’d., 390 F. 3d 1210 (10th Cir. 2004), the Tax Court provided perhaps one of the best arguments for a free-standing, comprehensive appraisal report:

Respondent’s expert appears to be extremely well qualified but he favored us with too little of his thought processes in his report. In another area, for example, his report briefly referred to the projected earnings approach, but the discussion was too abbreviated to be helpful. His testimony on the computer models he used, while unfortunately never developed by counsel, suggested that a lot of work had been done but simply not spelled out in his report. That may also be the case in his price-to-earnings computations, but the Court cannot simply accept his conclusions without some guide as to how he reached [them].

2. Pure Reliance on Case Law for Discount

What constitutes the proper valuation discount is essentially case-by-case factual issue. Valuation discounts can be factored in as an element of the discount rate (sometimes characterized as implicit treatment) or applied as direct adjustment(s) to value after the enterprise level value has been determined. As such, pure reliance on case law for determination of valuation discounts is inadvisable, particularly when the economics, facts, and circumstances of the precedent cases do not reasonably parallel those of the subject interest. Nevertheless, some valuators have resorted to reliance on case law for determination of valuation discounts. In Berg Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1991-279), the Tax Court was unimpressed with this practice:

The fact that petitioner found several cases which approve discounts approximately equal to those claimed in the instant case is irrelevant.

3. Failure to Find Available Information

Very few things look worse for a valuator than when he or she cannot find information that the opposing valuator finds. This happened in Barnes v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1998-413):

[Valuator A] used the market or guideline company approach to estimate the value of Home and Rock Hill stock, but he excluded three companies that [Valuator B] used as comparables because he did not have their market trading prices as of the valuation date. In contrast, [Valuator B] apparently easily obtained the stock prices by contacting the companies.

4. Insufficient Explanation of Assumptions

It is important to explain any assumptions that you make in a valuation report. In Bailey Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2002-152. See also, for example, NACVA/IBA Professional Standards Secs. IV(G)(9) and V(C)(11)), the Tax Court criticized the appraiser for failing to do so:

[He] offered no explanation or support for any of the many assumptions that he utilized in the just-described analysis. Nor did he offer any explanation or support for his conclusion that the discount related to stock sale costs should be 6 percent. An expert report that is based on estimates and assumptions not supported by independent evidence or verification is of little probative value or assistance to the Court.

5. Failure to Explain Weightings

It is essential that you include a significant discussion in the valuation report of how you weighted products of various multiples in your conclusion of value. This did not happen in True Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2001-167, aff’d., 390 F. 3d 1210 (10th Cir. 2004)), as the Tax Court pointed out:

[The valuator’s] report’s guideline company analysis was even more questionable. It provided no data to support the calculations of … pretax earnings and book value for either the comparable companies or True Oil. Further, [he] did not explain the relative weight placed on each factor….Without more data and explanations, we cannot rely on [his] report’s valuation conclusions using the guideline company method.

Where different valuation methods yield differing indications of value, you must be very clear about how you use them to arrive at a conclusion of value.

It sometimes is tempting to simply weight the indications equally. What is more important, however, is to have an explanation for the weighting of the indications of value, whatever they might be. In Hendrickson Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1999-278. See also Pratt with Niculita, Valuing a Business, 5th Ed., McGraw-Hill, NY, 2008, pp. 477-482), the Tax Court criticized the work of a valuator who simply gave the indications of value equal weight without bothering to explain why.

(Editor’s note: Some valuation books include complete chapters on reconciling the three approaches (market, asset, and income). An example is Chapter 15 of The Market Approach to Valuing Businesses, 2nd Edition, by Shannon P. Pratt and Alina V. Niculita. Wiley, NJ, 2006.)

6. Failing to Justify Capitalization or Discount Rates

You cannot simply pull a capitalization or discount rate out of thin air; you must justify it. This seems to have been an issue in Morton v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1997-166):

[The valuator] testified that venture capitalists generally require between 30- and 60-percent return, and that his 35 percent discount rate was “conservative.” However, [he] did not provide any objective support, either at trial or in his expert report, for selecting a discount rate in this range.

7. Inadequate Guideline Company

You are usually required to include the names of guideline companies in the valuation report. This was not done in Jann Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1990-333. See also AICPA Statement on Standards for Business Valuation, Paragraph 61), where the Tax Court pointed out:

[The valuator’s] report referred to comparable companies but did not identify them; did not state whether [he] used average earnings or a weighted average earnings in his analysis; referred to a standard industrial classification number but did not identify it; and did not explain how he arrived the price-earnings ratio of 9.8.

In True Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2001-167, aff’d., 390 F. 3d 1210 (10th Cir. 2004)), the Tax Court criticized one of the taxpayer’s valuators, stating:

[He] provided no data showing: (1) How he computed the guideline company multiples or the Belle Fourche financial fundamentals, (2) which of three multiples he applied to Belle Fourche’s fundamentals, or (3) how he weighed each resulting product. Without more information we cannot evaluate the reliability of [his] results.

8. Failure to Think Like An Investor

In Newhouse Estate v. Commissioner (94 T.C. 193 (1990)), the Tax Court concluded:

None of respondent’s expert witnesses testified that they would have advised a willing buyer to use the subtraction method in deciding the value of the stock. None could testify that they had ever advised the use of the subtraction method in advising buyers or sellers of closely held stock in any comparable situation.

9. Lack of Independence

The work of valuators and appraisers must be independent, which means having no personal interest in the company being valued or the outcome of litigation. In fact, appraisers usually must certify that they are independent. (See for example 2010-2011 USPAP Ethics Rule line 207, NACVA/IBA Professional Standards Sec. II(J), Former NACVA Professional Standards Sec. 1.2(k), ASA BVS Sec. III(A), Former IBA Business Appraisal Standards Section 1.3, and AICPA Statement on Standards for Valuation Services Paragraph 15.)

In McCormick Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1995-371), the Tax Court noted the following about a lack of independence:

Petitioners’ proffered ‘expert’ was John McCormick III, son of petitioner.

In Cook Estate v. Commissioner (86-2 USTC Par. 13.678 (D.C. W.D. Mo. 1986)), the Tax Court disregarded testimony of a person who was too close to the action:

[The appraiser’s] valuation of the stock at issue is not persuasive because of his self-interest. [He] is….president of Central Trust Bank…and the co-executor of Howard Winston Cook’s estate.

10. Improper Classification of Subject Company

In Bennett Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1993-34), the Tax Court felt that the IRS appraiser failed to properly characterize the subject company:

…in his report, [the valuator] should have characterized Fairlawn as a corporation actively engaged in commercial real estate management rather than wholly as an investment or holding company.

11. Inconsistency

Contradicting your own assertions without adequate explanation can undermine your authoritativeness, whether it’s done within a single valuation report, or from one report to another, or between writings of various kinds. For example, assumptions used in more than one valuation approach, within a single report, must be consistent. That rule was violated in Bell Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1987-576):

Furthermore, the rates of return applied by [the valuator] in the excess earnings method bore no relationship to the capitalization rate [he] used in the capitalization of income stream method. We believe his choice of varying rate indicates a result-oriented analysis. An appropriate capitalization rate is determined by the comparable investment yield in the market not by the choice of a valuation method. [The valuator] made little effort to identify comparable investments.

Any significant discrepancy between your report and your testimony can compromise your credibility, as the Tax Court demonstrated in Moore v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1991-546):

First, his report and trial testimony are inconsistent in that they indicate different methodologies for valuing the partnership interests. The report indicates that he valued the interests by discounting the fair market value of the business to reflect the lack of control and illiquidity associated with the minority interests. His trial testimony indicates that he valued the partnership interests under the procedure prescribed in Rev. Rul. 59-60, 1959-1 C.B. 237.

Valuators must use commercially available data consistently as well. In Klauss Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2000-191), the Tax Court said that:

[The valuator] testified that it is appropriate to use the Ibbotson Associates data from the 1978-92 period rather than from the 1926-92 period because small stocks did not consistently outperform large stocks during the 1980s and 1990s. We give little weight to [his] analysis. [He] appeared to selectively use data that favored his conclusion. He did not consistently use Ibbotson Associates data from the 1978-92 period; he relied on data from 1978-92 to support this theory that there is no small-stock premium but use an equity risk premium of 7.3 percent from the 1926-92 data (rather than the equity risk premium of 10.9 percent from the 1978-92 period.

In Caracci v Commissioner (118 T.C. 379 (2002), rev’d 456 F. 3d 444 (5th Cir. 2006)), the Tax Court used the valuator’s past writings against him in the selection of a price-to-revenue multiple:

Moreover, in an article published [in Intrinsic Value] in the spring of 1997, [the valuator wrote] that for the prior two years, a standard market benchmark for valuing traditional visiting nursing agencies, such as the Sta-Home tax-exempt entities, was a price-to-revenue multiple of .55. We fail to understand why the Sta-Home tax-exempt entities had a much lower multiple of 0.26.

There may be a legitimate basis for valuing the same interests using different methods in sequentially issued reports. But in True Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2001-167), the Tax Court found that the valuator’s inconsistent application of valuation methodology was a problem, commenting:

[His report] calculated the equity value of Dave True’s 68.47 percent interest in Belle Fourche on a fully marketable non-controlling basis without first valuing the company as a whole. This significantly departed from the initial…report’s guideline company approach, which first valued the company on a marketable controlling basis, and then applied a 40 percent marketability discount. Even though both reports used the guideline company method, we believe the approaches were substantially different and find it remarkable that both reports arrived at the same ultimate value of roughly $4,100,000 for Dave True’s interest. This suggests that the final…report was result-oriented.

Finally we have an example of inconsistent use of pre- and post-tax figures. In Dockery v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1998-114. See also ASA BV Sec. IV(JV)(D)), the valuator:

[M]isapplied the price/earnings capitalization rate of 5 used in Estate of Feldmar to convert Crossroads’ weighted average earnings, in that the Court in Estate of Feldmar applied the capitalization rate to post-tax earnings and [the valuator] applied it to pre-tax earnings.

12. Incorrect Definitions

In Hall Estate v. Commissioner (92 T.C. 312 (1989)), the Tax Court determined that the valuator had incorrectly defined cash flow:

In its application of the discounted future cash flow valuation, [he] incorrectly defined cash flow as net income plus depreciation, omitting consideration of deferred taxes, capital expenditures, and increases in working capital.

In Heck Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2002-34), the Tax Court determined that the IRS appraiser defined the term “guideline company” too narrowly:

[The appraiser] argues that only companies that are ‘primarily champagne/sparkling wine producers like Korbel’ constitute permissible guideline companies. Because no such publicly traded company existed, Dr. Bajaj rejected the market approach. We find [the appraiser’s] approach to be unduly narrow (in theory), in light of the case law cited in the text.

13. Making the Hypothetical Buyer Too Real

The buyer and seller in the fair market value calculus must be hypothetical. In Simplot v. Commissioner (249 F. 3d 1191 (9th Dir. 2001)), the Ninth Circuit called down the Tax Court for failing to adhere to this standard, noting:

The Tax Court in its opinion accurately stated the law: ‘The standard is objective, using a purely hypothetical willing buyer and willing seller….The hypothetical persons are not specific individuals or entities.’ The Commissioner himself in his brief concedes that it is improper to assume that the buyer would be an outsider. The Tax Court, however, departed from this standard apparently because it believed that ‘the hypothetical sale should not be constructed in a vacuum isolated from the actual facts that affect value.’ Obviously the facts that determine value must be considered.

The facts supplied by the Tax Court were imaginary scenarios as to who a purchaser might be, how long the purchaser would be willing to wait without any return on his investment, and what combinations the purchaser might be able to effect with Simplot children or grandchildren and what improvements in management of a highly successful company an outsider purchaser might suggest. ‘All of these factors,’ that is, all of these imagined facts, are what the Tax Court based its 3 percent premium upon. In violation of the law the Tax Court constructed particular possible purchasers.

14. Undue Reliance of the Work of Other Valuators

It is not unusual for a business valuator to rely in part on the efforts of a colleague, often a real estate or other personal/tangible property appraiser. The relying valuator cannot blindly rely on the work of others, but must make some baseline assessment of the accuracy and completeness of the other appraiser’s work. In Northern Trust Co. v. Commissioner (87 T.C. 349, aff’d sub nom. Citizen’s Bank & Trust v. Commissioner, 839 F. 2d 1249 (7th Cir. 1988)), the Tax Court criticized a valuator’s opinion, noting:

[He] explained that he relied on the opinion of several local real estate appraisers [but admitted that those appraisers] never viewed the property prior to determining the appropriate adjustments. Indeed, the record contains no evidence explaining the basis of these adjustments.

15. Reliance on an Irrelevant Study

You have a duty to investigate or otherwise inquire about research, studies, reports, and other information on which you rely. In Kraft, Inc. v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1988-511. See also 94-1 USTC Par. 50,080 (Cl. Ct. 1994)), the court criticized the use of incomplete data:

Foremost is that the data used by [the valuator] from Table No. 58 of the Pitcher Report, included in Exhibit 208, and used in the ‘Knutson formula,’ cannot reasonably be construed to represent conditions in milk markets elsewhere in the United States, or even within the New York City metropolitan area. It is true that the Pitcher Report was a detailed study of the milk market in New York State, rich with anecdotal stories and complex analyses of a very troubled industry crying for help from its elected and appointed government officials. Nonetheless, the data used by [the valuator] was only for the New York City metropolitan area; it did not include data gathered from dairies statewide, from other New York State cities, and from the larger NYC metropolitan area dairies. The failure to include data from the larger dairies is significant.

16. Cherry-Picking Valuation Multiples

In Wall v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 2001-75), the Tax Court had this to say about the valuator’s narrow selection of multiples:

It did not use all the guideline company multiples but instead picked and chose among the lowest ….[The valuator’s] use of the two or three lower multiple companies is inconsistent with the conclusion expressed elsewhere in her report that, even after the decline in Demco’s earnings had been taken in account, Demco’s profitability and risk levels were close to or at the industry norm. It also may be inconsistent with her conclusion that the seven companies she identified as comparable were in fact comparable to Demco.

In Gallo Estate v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo 1985-363), the Tax court was even more pointed in its cherry-picking criticism:

In valuing Gallo under each of the five methods based on comparables that he used, [the valuator] assigned to Gallo ratios that would result in the highest possible valuations. [His] method was pervasive and absolute: he made no real attempt to compare Gallo with any of the individual comparables. Even if Gallo were an above-average company, which is was not when ranked among the comparables, it would be unreasonable to expect Gallo to be most attractive with respect to each and every ratio. None of the 16 comparables was so positioned.

Conclusion

In this article we presented 16 kinds of mistakes made by valuation experts, as reported in federal courts in tax decisions. Just because one judge in one case calls something a mistake doesn’t make it a mistake in all cases. But we think the above examples are indeed instructive in most valuation situations.

L. Paul Hood, Jr., Esq.

The University of Toledo Foundation

paul@acadiacom.net

Timothy R. Lee, ASA

Mercer Capital

leet@mercercapital.com

Note: This article originally appeared in the July/August 2013 issue of The Value Examiner. It was adapted from Chapters 17-18 of A Reviewer’s Handbook to Business Valuation by L. Paul Hood, Jr., and Timothy R. Lee, (John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2011). For book details, see www.mercercapital.com or http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-0470603402.html.

Leverage Lending, Dividend Recaps, and Solvency Opinions

The market for corporate loans and high yield bonds remains torrid in spite of the move higher in intermediate- and long-term Treasury rates since May. Leveraged loan issuance totaled $736 billion through August vs. $387 billion last year-to-date. High yield bond issuances totaled $208 billion, up from $189 billion. The majority of activity reflects refinancing-related volume rather than new money borrowing. A sub theme within the refinancing trend is the dividend recap. This presentation examines the pros and cons of such transactions that unlock value for equity holders, create incremental risk for lenders, and the importance of solvency opinions as part of the process.

Presented September 17, 2013

Specialty Finance Sector Shows Signs of M&A Life

The M&A market for banks remains steady relative to Street expectations for a quicker pace, given well-documented earnings and regulatory challenges that smaller institutions face. Year-to-date through August 19, 2013, there were 137 announced bank and thrift transactions, which equates to about 210 deals on an annualized basis. This compares to 251 announced deals in 2012 and 178 in 2011. Pricing, as measured by the average price/tangible book multiple of 117%, is comparable to median pricing observed the past few years; however, P/E ratios have declined as earnings have recovered. The median P/E for 2013 was 23.2x, compared to 33.0x in 2012.

In particular, the specialty finance sector has seen a steady pace of transactions. According to SNL Financial, there have been 43 acquisitions of specialty finance companies year-to-date by banks and non-banks, for an aggregate value of $7.4 billion. There were 80 deals valued at $10.8 billion in 2012 and 70 deals valued at $36.0 billion in 2011. Since 2008, the average price/book multiple has ranged between 187% (2011) and 78% (2010). The median year-to-date price/book multiple was 124%, while the median P/E was 7.8x. Sector pricing averages should be taken with a grain of salt as the homogeneity in the banking sector does not apply to the same degree in specialty finance.

While interest in mortgage banking may be waning with rising rates, other specialty finance sectors, such as commercial real estate (CRE), are receiving more attention as banks and non-banks return to the sector. As an example, Capital One Financial Corporation (COF) announced on August 16, 2013 that it would acquire Beech Street Capital for an undisclosed price. Beech Street was founded in 2009 by long-time banking executive Alan Fishman along with employees from Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and other lenders. Beech Street focuses on multi-family lending as a Fannie Mae “Delegated Underwriting and Servicing” (“DUS”) lender. Such firms are approved to underwrite, close, and deliver most loans without a prior review by Fannie Mae. Capital One is acquiring one of the 24 designated DUS firms and will presumably gain a competitive advantage in underwriting multi-family loans at a time when the sector is benefiting from a resurgence of apartment construction.

Another transaction of note is the July 22, 2013 announcement that PacWest Bancorp (PACW) will acquire CapitalSource Inc. (CSE) for $2.3 billion of stock and cash. Pricing equated to 169% of June 30 tangible book value and 19x consensus 2013 EPS. Although CapitalSource’s primary subsidiary operated as a bank via its California industrial loan charter, the Company is more akin to a commercial finance company in a bank wrapper. PacWest will obtain a prodigious asset generator that will be funded with its core deposits.

Acquisitions of specialty finance companies by banks are not a panacea for challenges that face the industry; however, in some instances a transaction that is thoroughly vetted, well-structured, and attractively priced can provide the buyer a new growth channel while also obtaining revenue and earnings diversification. At Mercer Capital we have three decades of experience in valuing and evaluating a range of financial service companies for banks, private equity, and other investors. We would be happy to assist you in evaluating an opportunity that your institution may be considering.

Evaporating Gains

Comments by Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke in the second quarter of 2013 resulted in significant increases in Treasury rates during the quarter, particularly for longer-term securities. In May, Bernanke testified before Congress and outlined the Fed’s eventual approach for exiting its accommodative monetary policy, which has included very low interest rates as well as purchases of mortgage-backed securities and Treasuries. Bernanke noted that the Fed would likely begin its exit strategy by gradually reducing asset purchases, prior to a focus on increasing interest rates. Prior releases by the Federal Open Market Committee indicated that rate increases likely will not begin until the unemployment rate has fallen below 6.5%, assuming inflation projections remain in line with longer-term goals. Bernanke’s comments before Congress suggest, however, that some tightening of monetary policy could come earlier, through the reduction in asset purchases. In response to Bernanke’s comments, longer-term interest rates began to tick up through May and into June.

On June 19th, Bernanke said in a press conference that the Fed could begin to reduce its asset purchases as early as the end of 2013 and could potentially cease such purchases in mid-2014. The near-term timeline for reducing asset purchases spurred a spike in interest rates that compounded the effect of the already-increasing trend in rates observed through May. Rates continued to exhibit volatility throughout the rest of June as markets reacted to Bernanke’s comments.

Treasury Rates

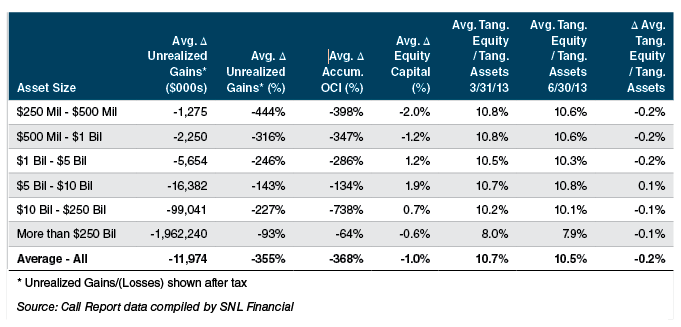

The interest rate increases in the latter part of second quarter resulted in the evaporation of unrealized gains in banks’ bond portfolios, which had been at very high levels given the persistently low rate environment. The table below summarizes the extent of losses in unrealized bond gains for banks in the second quarter. The number of banks with assets over $250 million reporting unrealized gains embedded in their bond portfolios fell from 1,985 at March 31, 2013 to 1,018, or 49% fewer, while the number of banks reporting embedded losses tripled from 477 to 1,427.

At March 31, 2013, banks reported unrealized gains representing an average of 1.97% of their total Available for Sale (“AFS”) portfolios. That figure declined to 0.84% at June 30, a decline in unrealized gains of 1.13% of total AFS. On average, banks lost more than 350% of reported amounts of unrealized gains embedded in bond portfolios, resulting in commensurate reductions in accumulated other comprehensive income. The impact of the lost AOCI on tangible equity, however, was moderated by the trend of improving earnings in the industry, and on average, equity capital declined by just 1%, while the average tangible equity/tangible assets ratio fell from 10.7% at March 31, 2013 to 10.5% at the end of second quarter.

The effect of volatility in unrealized bond gains may create fluctuations in tangible equity capital, but its effect on regulatory will be much more modest, given the recent issuance of the final Basel III capital rules, which require only banks with more than $250 billion in assets to include such gains in regulatory capital measures beginning in 2014. Most smaller banks will not be required to include unrealized gains in regulatory capital calculations, with the exception of banks with foreign exposures exceeding $10 billion.

Portfolio Valuation Can Be Complex, Risky

Fair Value Measurement for PE Firms is Under the Microscope

Valuation of PE portfolio investments for financial reporting can be challenging for many reasons. PE investments are, by nature, illiquid. Portfolio companies are not publicly traded, and holding periods are generally long. PE investments often employ complex capital structures that include several tranches of equity, debt or hybrid securities with differing rights to intermediate and exit proceeds. In addition, derivative instruments are also popularly used in incenting management teams.

Increasing Risk of Conflict of Interest

Market participants are increasingly sensitive to (the appearance of) conflicts of interest in PE valuations. In the absence of public, transparent information, investors have to rely on valuation marks provided by PE managers to assess performance, review allocations, determine compensation and fulfill their own reporting requirements. Regulatory agencies, including the SEC, are increasingly scrutinizing valuation practices within PE and other alternative investment managers.

Mercer Capital Has the Technical Expertise to Address Complicated Valuation Issues

In the absence of public price discovery, analysts must rely on or devise models to conduct valuations of portfolio companies and investments. At the same time, accounting principles prescribe maximizing the use of publicly observable inputs in the valuation models. A defensible valuation opinion needs to consider, conduct, and document a number of procedures including historical financial review, independent analysis of public guideline or comparable companies and private transactions, evaluation of acceptable and relevant income methods (capitalization or discounted cash flow), and tests for internal consistency.

Mercer Capital has years of experience in providing third-party valuation opinions on illiquid investments to PE clients’ and other stakeholders’ satisfaction. Our recent presentation, “Best Practices for Fair Value Measurement,” available at http://mer.cr/pe-val-ppt, throws some light upon a number of valuation issues specific to PE portfolios.

Hiring an Independent Third-Party Valuation Specialist Reduces Risk of Conflict of Interest

It is vital that analysts exercise impartiality in conducting portfolio valuations. Larger PE funds increasingly rely on valuations prepared by third-party specialists to ensure objective reporting of portfolio investments. Investor-facing groups including the Institutional Limited Partner Association, European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association, and the Alternative Investment Management Association acknowledge and recommend the use of independent third-party valuation specialists.

Contact a Mercer Capital professional to discuss your needs for independent valuation and consulting services.

Your Business Will Change Hands: Important Valuation Concepts to Understand

In this article, we provide a broad overview of business value and why understanding basic valuation concepts is critical for business owners. Why is this valuation knowledge important? Because businesses change hands much more frequently than one might think. In fact, every business changes hands at least every generation, even if control is maintained by a single family unit.

Business Press Focuses on Public Companies

According to statistics about business size from the U.S. Census Bureau, there are about six million businesses with payrolls (meaning these businesses employ people) in the United States.[1] A little more than three and a half million U.S. businesses have sales of less than $500 thousand. Without any disrespect, these businesses are often referred to as “mom and pop” operations because their basic function is to provide jobs for the owner(s) and sometimes a few other people.

About two million businesses have annual sales between $500 thousand and $10 million.[2] This segment of the business community is generally given credit for the majority of job growth. Only about 200 thousand businesses have annual sales exceeding $10 million.[3]

At the top of the business pyramid are public companies. Of these, as of 2012, only about four thousand have active public markets for their shares with regular stock pricing and volume information available.[4] Because of their size and visibility, this relatively small group of public companies gets the lion’s share of coverage in the business press. As a result, most of the popular business press coverage of valuation issues relates to public companies.

Most Companies are Privately Owned

But most of the businesses in corporate America are closely held, or private corporations. This means that most of the business owners in corporate America are not in public companies, but in generally smaller entities owned by a single, or a small number of shareholders. Therefore, it’s important for these business owners and their advisors to have an understanding of the nature of value in these businesses.

Private Businesses Change Hands Frequently

Most business owners, and, quite often, their advisors, have inaccurate conceptions of the value of their businesses. This is not surprising, because there is no such thing as “the value” of any business. Value changes, often rapidly, over time. Yet it is important for business owners to have current and reasonable estimates of the values of their businesses for numerous reasons, including ownership transfer.

There are many reasons for ownership transfer, including:

- The death of the primary owner. At this point, it is clear that control of a business will pass to someone else.

- The departure of a key employee. This departure may trigger the necessity to sell a business if he or she takes away the key contacts or critical energy that keep things going and growing

- The owner gets “tired” and decides to sell. This is an unbelievably frequent reason why business ownership transfers. Unfortunately, if a business owner waits until he or she is tired, they are already on the down side of the value curve. Tired owners almost unavoidably transmit their “tiredness” to employees and customers in many subtle and not so subtle ways. In the process, their businesses lose a vital life force critical for ongoing growth and success.

- An unexpected offer. Occasionally, a business owner will receive an unexpected offer to purchase the business and will, quite suddenly, sell out to take advantage of the situation.

- Business reversals occur. Perhaps a company fails to adapt to a changing market, competition arises from unexpected quarters, or an accident or bad luck generates substantial losses. Sometimes the affected businesses never recover, and at other times, a forced sale results.

- A divorce. Divorces involving family-owned or closely held businesses occur. Wild card divorce settlements or emotional changes resulting from a divorce can also create the necessity or desire to sell.

- Life-changing experiences. Business owners sometimes encounter life-changing experiences, such as heart attacks, cancer, close calls in accidents, the death of a parent, spouse or friend, or other. The shock of such experiences sometimes fosters a strong desire to “do things differently with the rest of my life.” Business transfers can be the eventual result of these life-changing experiences.

- Gift and estate tax planning. Gift and estate tax planning by business owners is a normal means of business transfer. The absence of proper gift/estate tax planning can also precipitate the forced sale of a business if a business owner’s estate lacks the liquidity to handle estate taxes, or if a failure to plan for orderly and qualified management succession cripples the business when the owner is no longer there.

- The second generation is not up to the task. There is ample proof that most businesses never survive to the second generation. Unfortunately, family businesses which do make it past the founder’s death sometimes never survive the ascendancy of the second generation of management and have to be sold.

- Normal lifetime planning. Finally, businesses sell as the result of normal lifetime planning by their owners who plan for and execute the sale of their businesses (or transfer them through gifts) on their own timetables and terms.

The Business Transfer Matrix

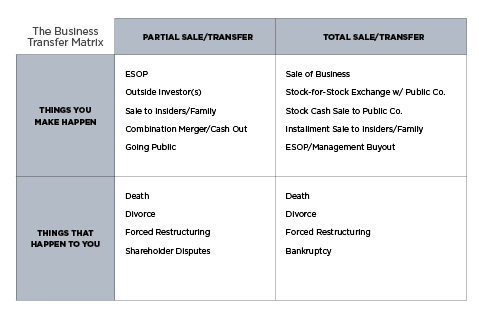

If you don’t believe that businesses change hands, examine the Business Transfer Matrix in Figure 1.

When a business changes hands, there will be either a partial transfer of ownership (in the form of gifts, sales to employees, going public, etc.) or a total transfer of ownership (through outright sale or death).

The Business Transfer Matrix also indicates that ownership transfers are either voluntarily or involuntary because we do not always control the timing or circumstances of sale.

The Common Thread Behind Most Business Transfers

Unfortunately, most business owners don’t plan for the eventual transfer of their business. In our experience, most business sale or transfer decisions are made fairly quickly. In many cases, business owners never seriously contemplate the sale of their businesses until the occurrence of some precipitating event, and shortly thereafter, a transfer takes place.

The logical inference is that many, if not most, business sales occur under less than optimal circumstances.

The only way business owners can benefit is to constantly do the right things to build and preserve value in their businesses, whether or not they have ever entertained a single thought about eventual sale.

In other words, owners should operate their businesses under the presumption that it may someday (maybe tomorrow) be necessary or appropriate to sell. When the day comes, business owners will be ready – not starting to get ready and already behind the eight ball.

What a Business Owner Thinks About the Value of Their Business Ultimately Doesn’t Matter

It is a hard truth for many business owners to learn that what they think regarding the value of their business doesn’t matter. The value of any business is ultimately a function of what someone else with capacity (i.e., the ability to buy) thinks of its future earning power or cash generation ability.

For other transactions with gift or estate tax implications or with legal implications for minority shareholders, what a business owner thinks still doesn’t matter. What then becomes important is the value a qualified, independent business appraiser or the court concludes it is worth. In so doing, the appraiser or the court will simulate the arms’ length negotiation process of hypothetical willing buyers and sellers through the application of selected valuation methodologies.

Theoretically, the value of a business today is the present value of all its future earnings or cash flows discounted to the present at an appropriate discount rate. To determine a business’s worth, determine two things: 1) What someone else (with capacity) thinks the company’s earnings really are; and 2) what multiple they will pay. Simplistically, we are saying:

Hypothetical (or real) buyers of capacity will make reasonably appropriate adjustments to the company’s earnings stream in their earning power assessments. In addition, they will incorporate their expectations of future growth in earning power into their selected multiples (price/earnings ratios). Or they will make a specific forecast of earnings into the future and discount the future cash flows to the present.

A Conceptual Viewpoint of the Value of Companies

Now let’s talk a bit about the value of companies from a conceptual viewpoint by beginning with a familiar term and its definition: Fair Market Value.

A hypothetical willing buyer and a hypothetical willing seller, both of whom are fully or at least reasonably informed about the investment, neither of whom are acting under any compulsion, and both having the financial capacity to engage in a transaction engage in a hypothetical transaction

That may not sound like the real world, but it is the way that appraisers attempt to simulate what might happen in the real world in actual transactions in their appraisals.

And it is the way that business owners state in agreements – quite often in buy-sell agreements, put agreements, and other contractual relationships – that value will be determined.

Just so everything is crystal clear, this concept of fair market value can be considered on several levels.

How is Value Determined?

The basic value equation is also known as the Gordon Model:

As mentioned previously, value is also presented as:

The multiple is calculated as follows:

Another multiple:

A company’s price/sales ratio is a function of the margin, say pre-tax earnings, and the appropriate multiple. If companies in the industry tend to sell in the range of 50 cents per dollar of revenue, that might be because the typical pre-tax margin is around 10% and the pre-tax multiple is about 5x.

The multiples of sales that people talk about obviously come from somewhere. Now we know where they come from.

If Value = Earning x Multiple, what about Earnings?

There are three ways to increase Earnings:

- Increase Total Revenue and hold Total Costs constant

- Hold Total Revenue constant and decrease Total Costs

- Increase Total Revenue and decrease Total Costs

At the margin, if a business increases its costs at a slightly slower rate than its revenues increase, its margins will increase and there will be a multiplicative impact on earnings growth.

If a company’s margins aren’t where they need to be, a business owner should begin a conscious effort each period to hold cost increases to something under revenue increases. If this is done, single digit revenue growth can be turned into double digit earnings growth – at least until margins normalize. We call this “margin magic.” In the process, the business owner will have begun to optimize the value of the business.

Therefore, the multiple can be characterized as:

- 1 / (Risk – Growth)

- Multiple = f (controllable, noncontrollable factors) [risk, and growth]

- Value = f (expected cash flow, risk, and expected growth)

Six Different Ways to Look at a Business

Along the road to building the value of a business it is necessary, and indeed, appropriate, to look at the business in a variety of ways. Each provides unique perspective and insight into how a business owner is proceeding along the path to being ready for sale.

So, how does a business owner look at their business? And how can advisers to owners help owners look at their businesses? There are at least six ways and they are important, regardless of the size of the business.

- At a point in time. The balance sheet and the current period (month or quarter) provide one reference point. If that is the only reference point, however, one never has any real perspective on what is happening to the business.

- Relative to itself over time. Businesses exhibit trends in performance that can only be discerned and understood if examined over a period of time, often years.

- Relative to peer groups. Many industries have associations or consulting groups that publish industry statistics. These statistics provide a basis for comparing performance relative to companies like the subject company.