Bank Merger & Acquisition Review: 2011 & Q1 2012

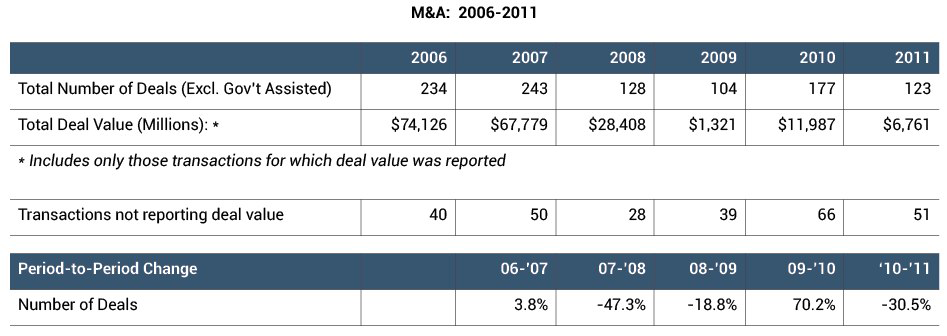

Despite an anticipated surge of transactions within the banking industry, bank merger and acquisition activity declined in 2011 compared to the prior year, hindered by a weak economic recovery, mounting regulatory pressures, and, according to some analysts, excessive seller expectations. Deal volume excluding government assisted transactions decreased 15.8% in 2011 from 2010 levels and approximated 2008 levels. It appears deal volumes bottomed out in 2009 at a total of 104 for the year. Unfortunately, the number of transactions not reporting a deal value has increased in recent periods (from 39 in 2009 to 51 in 2011), making a comparison of trends in deal values difficult. The number of deals presented is exclusive of FDIC-assisted transactions, which decreased to 92 in 2011 from 157 during 2010.

Deal value (for those transactions which reported it) totaled $6.8 billion in 2011 versus $11.7 billion in the prior year. Total deal value included PNC’s $3.5 billion acquisition of RBC Bank, which was announced in the second quarter of 2011, completed in the first quarter of 2012, and represented 51% of total reported deal value in 2011. Comerica’s $1.0 billion acquisition of Sterling Bancshares (announced in the first quarter and completed in the third quarter) accounted for 15% of total deal value during the year.

Notably, total deal value for transactions in 2010 included several sizeable acquisitions, such as BMO’s purchase of Marshall & Ilsley Corporation ($5.8 billion), Hancock Holding Company’s purchase of Whitney Holding Corporation ($1.8 billion), and First Niagara Financial Group’s purchase of NewAlliance Bancshares, Inc. ($1.5 billion). The following table provides additional perspective with regard to transaction activity in the banking industry since 2006.

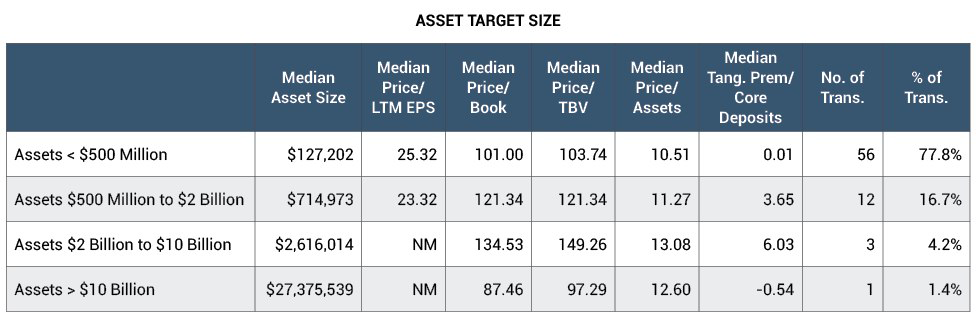

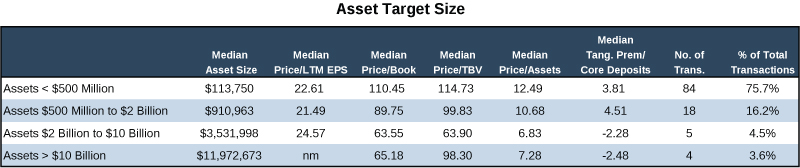

As in 2010, the majority of acquisitions involved sellers with assets less than $500 million. As shown below, for deals for which pricing multiples and deal value were available (a total of 72 transactions), 56 transactions, or more than 75%, involved targets with assets less than $500 million.

Twenty-one of the 72 transactions for which pricing information was available were all-cash transactions, 35 deals involved some mixture of cash and other consideration (generally common stock), and 10 transactions involved common stock as currency. The remaining deals were unclassified or not reported.

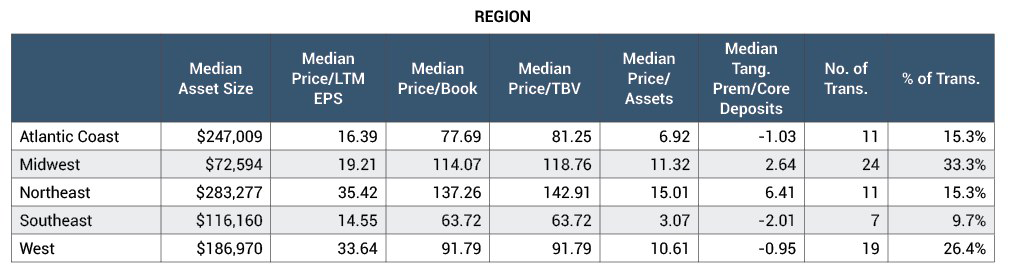

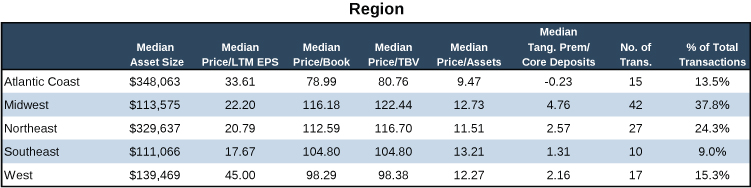

Regional economic viability again affected transaction volume during the year. Deal volume was highest in the Midwest and West regions1, which reported 24 and 19, respectively, of the 72 total transactions with pricing multiples. The Atlantic Coast and Northeast regions followed with 11 deals each in 2011. Seven transactions occurred in the Southeast region. For comparison, FDIC-assisted transactions, which totaled 92 in 2011 compared to 157 in 2010, continued to be concentrated in states with severely depressed real estate markets, such as Florida and Georgia (both in the Southeast region), which had 13 and 23 bank failures, respectively, during 2011. Illinois and Colorado followed with nine and five failures, respectively, and all remaining states reported less than five failures each during the year.

Through March of 2012, a total of 16 bank failures were reported with eight attributable to the Southeast region. Florida and Tennessee each reported two failures, while Georgia reported four, and Illinois reported three failures. For comparison, through March of 2012, transaction volume was higher with 56 total deals reported (compared to 47 in the first quarter of 2011). Total reported deal value through the first quarter of 2012 was also higher at $3.0 billion (compared to $1.5 billion in the first quarter of 2011) and included Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group’s $1.5 billion acquisition of Pacific Capital Bancorp as well as Prosperity Bancshares’ $529 million acquisition of American State Financial Corp. Deal volume in the first quarter of 2012 was weakest in the Northeast, where four transactions occurred, while deal volume was higher in the Midwest and Southeast, which reported 25 and 13 transactions, respectively.

Some analysts have attributed the heightened transaction activity in the first quarter of 2012 to the improved economy and an increased confidence among buyers, and, in particular, confidence with regard to loan portfolio assessment. Transaction activity going forward is expected to remain concentrated among smaller institutions in light of revenue and regulatory challenges. However, uncertainty concerning regulatory changes and the resulting burdens placed on institutions (smaller ones in particular), coupled with market volatility and the heated political climate, still looms, threatening any impending, potential surge of transaction activity.

Furthermore, capital raising remains difficult, and lackluster market activity caused many institutions to look to private equity firms as a source of capital in 2011. Preferred stock issuances were successful for several firms during the year, and some analysts expect more buyers to utilize such issuances to finance acquisitions when consolidation activity resumes.

Endnote

1 The regions include the following states:

- Atlantic Coast – Delaware, Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Washington, D.C.

- Midwest – Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Wisconsin

- Northeast – Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont

- Southeast – Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Tennessee

- West – Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, May 2012.

3 Ways a Loan Portfolio Valuation Is Helpful to the Acquirer

Mercer Capital works extensively with both the management of an acquirer and their loan review personnel (both internal and external) to obtain an in-depth understanding of loans being acquired. We provide a detailed valuation model along with extensive documentation to support our analysis of the fair value of the subject loans, reflective of the credit risk embedded therein.

Our clients find these analyses helpful both when assessing a target initially and when accounting for the acquired loans at the transaction closing date. Here are three ways that a loan portfolio analysis is helpful to your bank when considering an acquisition.

- Assess the Target’s Credit Risk More Quickly and Accurately. The successful acquirer typically assumes all the credit risk inherent in the target institution, and failure to properly assess this risk typically hurts the acquirer’s ability to generate a profitable return on the capital allocated to complete the acquisition. A timely and accurate valuation of the loan portfolio is necessary to assess the target’s credit risk prior to closing, particularly when the target is relatively weak and both information and time are limited.

- Improve the Decision-Making Process. By obtaining a loan portfolio valuation, managers and directors gain a better understanding of the credit risk inherent in the portfolio, and the outlook for future performance of different segments of and individual credits in the portfolio. This enhances discussions among management and directors and provides a more detailed basis for submitting offers for the target and estimating the pro forma impact on capital ratios and earnings from the acquisition. Additionally, having an independent third party analyze the target’s loan portfolio frees up members of the acquirer’s due diligence team to assess and resolve other merger-related issues.

- Reduce the Potential for an Accounting Surprise. Merger-related accounting issues for bank acquirers are often complex. An assessment of the loan portfolio prior to closing provides management, directors, and their auditors an opportunity to evaluate, in advance, the methodology employed to value the acquired loans, as well as the potential impact on the acquirer’s balance sheet and earnings going forward. This reduces the likelihood of surprises when the fair value of the loan portfolio is determined on the transaction closing date. Further, materially incorrect credit and interest rate marks relative to the loan portfolio valuation at the acquisition closing date leads to delays in subsequent monthly closings and the inability to meet other financial reporting requirements.

In addition to loan portfolio valuation services, we provide acquirers with valuations of other financial assets and liabilities acquired in a bank transaction, including depositor intangible assets, time deposits, and trust preferred securities. We are always happy to discuss your valuation issues in confidence as you plan for a potential acquisition. Give us a call today.

A Review of Bank Stock Performance in August 2011: The “New Normal?” and Other Observations

Bank stocks ended a particularly volatile month in August 2011 on something of a good note, which masked the intra-month volatility. Looking forward, does this greater stock price volatility represent a “new normal,” as banks face an environment marked by greater macroeconomic risk?

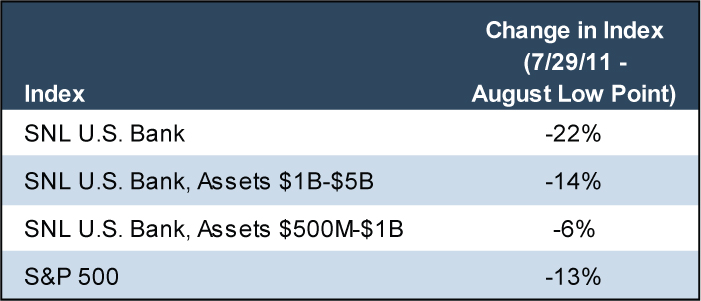

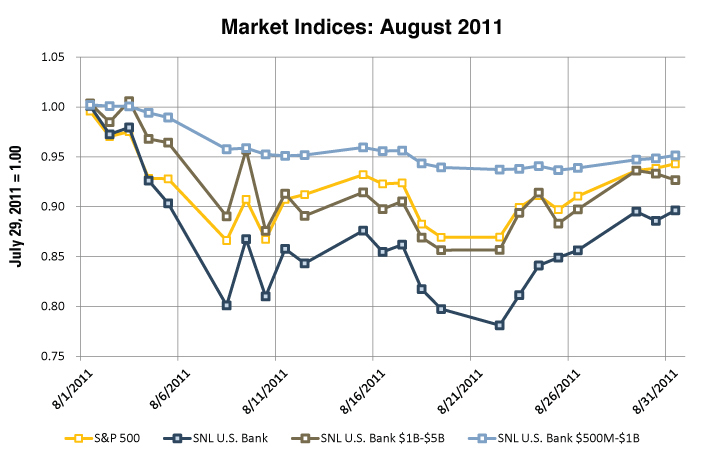

Three bank stock indices we track performed as follows in August, relative to the S&P 500:

While the deterioration in market values evident in the table above is substantial, the declines are even more significant when measured at points earlier in the month. Table 2 indicates the compression in market values between July 29, 2011 and the lowest point observed for each index in August1:

For example, the aggregate SNL Bank Index declined by 22% between July 29, 2011 and its August 22nd low, although subsequent gains cut this loss to 10% by month-end. Chart 1 provides daily observations for the four indices during August 2011.

The volatile performance appeared to be driven by various factors:

- Rising concern about a weakening global economic outlook and potential “double dip” recession in the U.S.;

- The inability of European governments to develop a successful strategy for managing their sovereign debt crisis, coupled with rising fears about a potential debt default by Spain and/or Italy;

- Concerns about the financial and reputational impact on larger banks of their entanglements with various issues and litigation related to securitized residential mortgages. This led to concerns that some banks (particularly Bank of America) may need to raise additional capital on dilutive terms (which Bank of America did via a preferred stock offering to Berkshire Hathaway); and,

- The U.S. debt downgrade by Standard & Poors.

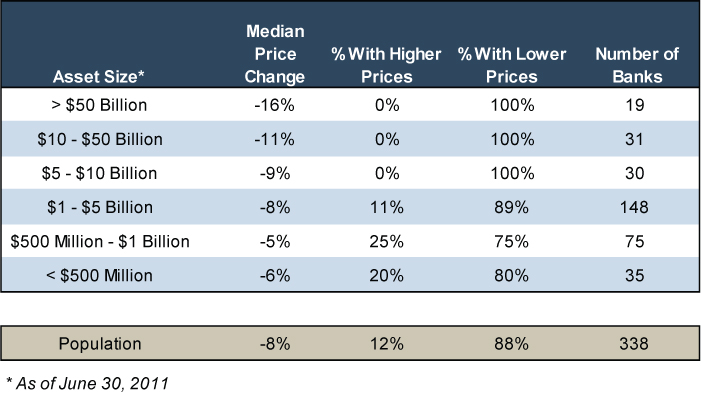

While these general factors affected most stocks in August, we attempted to isolate which factors most affected the performance of publicly traded banks in August. The following table shows the performance of banks in August stratified by asset size.

At August 31, 2011, no banks with assets exceeding $5 billion reported a higher stock price than at July 29, 2011, and larger banks generally reported weaker performance than smaller banks. This reflects several factors:

- The larger banks are more exposed to the lingering effects, such as lawsuits and loan repurchase demands, of residential mortgages originated at the peak of the real estate market;

- The larger banks may have direct exposure, albeit reportedly limited, to the sovereign debt of struggling European nations and entities located therein;

- The larger banks tend to be held more widely among various index funds, as compared to the smaller banks, which may create more selling pressure in a market where investors sell stocks in favor of safer alternatives; and,

- The smaller banks tend to trade less actively and often are less correlated with the broader equity market. Further, some of the smaller banks trade at very low nominal stock prices, due to their asset quality problems and capital shortfalls, and month-to-month movements in their stock price can be exaggerated and analytically less meaningful.

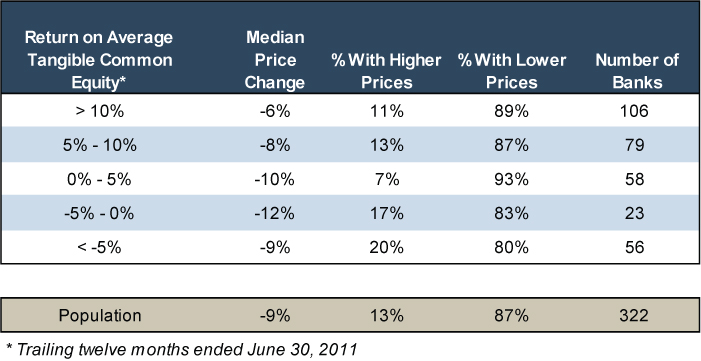

We also examined the relationship between August 2011 stock market performance and return on tangible common equity. As indicated in the following table, banks with stronger profitability generally performed better, as measured by the median change in their respective stock prices, providing some evidence that investors were more apt to avoid banks with lower profitability, since such banks may have less wherewithal to manage more distressed economic conditions.

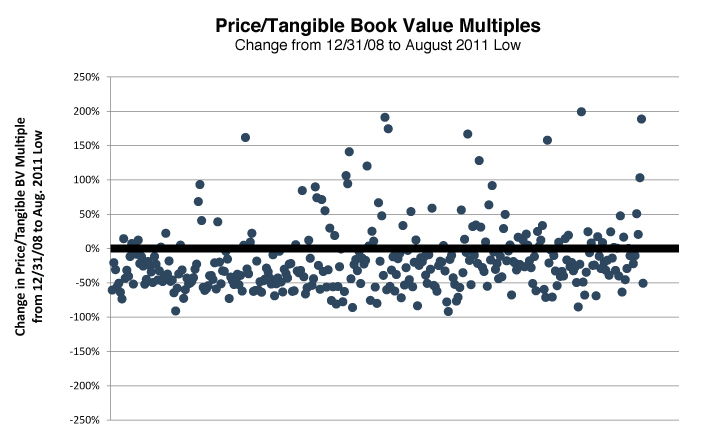

Given the depths to which some bank stocks fell in August, we thought it interesting to compare the price/tangible book value multiples, measured based on each bank’s lowest stock price during the month, to the price/tangible book value multiples observed as of December 31, 2008, which represents a proxy for the timing of most distressed period of the financial crisis. This analysis indicates the following:

- Only 80 banks had a higher price/tangible book value multiple at their August 2011 low than at December 31, 2008, which represents 24% of the population of actively traded banks. That is, despite the improving trends in credit quality and rising earnings, more than 75% of the publicly traded banks had lower price/tangible book value multiples at some point in August 2011 than at year-end 2008;

- The trend towards lower price/tangible book value multiples was not limited to smaller banks for which the effects of the weaker economic conditions were often not immediately evident in 2008. Even larger banks, such as Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo reported lower price/tangible book value multiples.

For perspective, the chart below plots the changes in the price/tangible book value multiples reported by the publicly traded banks between December 31, 2008 and their respective August 2011 lows.

Endnotes

1 These low points occurred on August 8th for the S&P 500; August 19th for the SNL Bank Index comprised of banks with between $1 and $5 billion of assets; August 22nd for the aggregate SNL Bank Index; and August 25th for the SNL Bank Index comprised of banks with between $500 million and $1 billion of assets.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch 2011-09, released September 15, 2011

Community Banks: Gradual Improvement Continues in the First Half of 2011

Earlier this year, we presented a review of community banks’ 2010 financial performance, which reflected a mixed bag – some metrics improved, while others deteriorated. With the mid-year filing cycle complete for banks’ Call Reports, we updated this analysis to assess whether the trends noted in 2010 have persisted. In general, we conclude that trends continue to improve, although the pace of improvement appears to be slowing for some metrics.

The analysis relies on a data set comprised of approximately 3,800 commercial banks with assets between $100 million and $5 billion. Additionally, we excluded banks owned by non-U.S. domiciled bank holding companies, subsidiaries of holding companies with more than $5 billion of assets, and banks with unusual levels of non-interest income or consumer lending. As a result, the data set does not have the bias evident in some analyses of aggregate banking industry data, which are weighted in favor of the largest domestic banks.

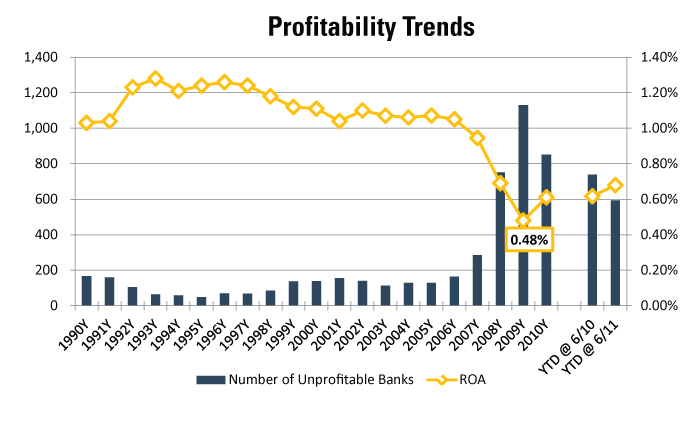

Income Statement

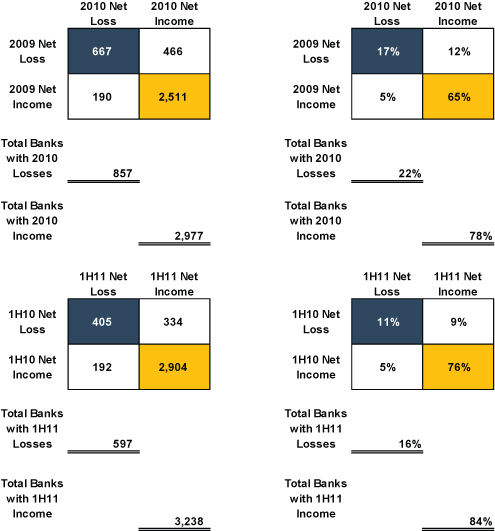

Reflecting community banks’ steady profitability improvement, 597 banks reported a loss in the first half of 2011, down from 739 in the first half of 2010 and 857 in fiscal 2010. However, the gradual nature of the improvement in performance is evident in the industry’s return on assets – the median bank’s return on assets improved from 0.62% in the first half of 2010 only to 0.68% in the first half of 2011, which remains well below the pre-crisis level that exceeded 1.00%. The improvement realized relative to the first half of 2010 is driven largely by lower loan loss provisions.

The following matrix groups community banks based on their net income into four categories including (a) positive net income in both the first half of 2010 and the first half of 2011, (b) net losses in both the first half of 2010 and 2011, or © positive net income in one period and a net loss in the other period. As indicated in the matrix, 76% of banks reported positive net income in both periods, while 11% reported net losses in both periods.

Figure Two

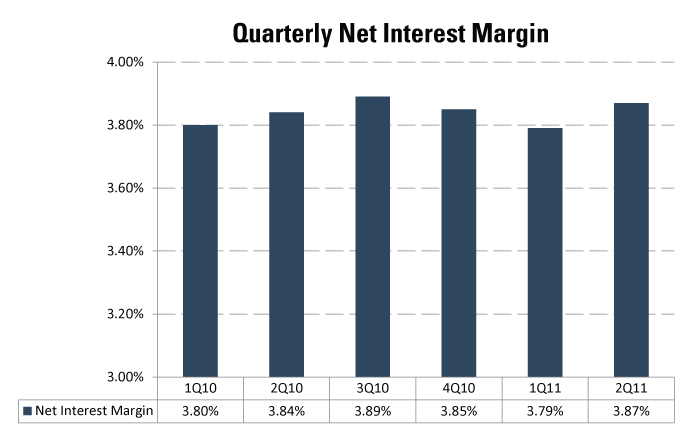

Net interest margin enhancement contributed to many community banks’ improving performance. For example, in fiscal 2010, net interest margin expansion benefited about 60% of the banks in the analysis. However, data from 2011 suggest that the trend of rising net interest margins is weakening. For the first half of 2011, approximately one-half of the banks in the sample reported higher net interest margins than in the first half of 2010.

After declining for the last two quarters, the median net interest margin widened in the second quarter of 2011, suggesting that community banks continue to benefit from deposit rate reductions.

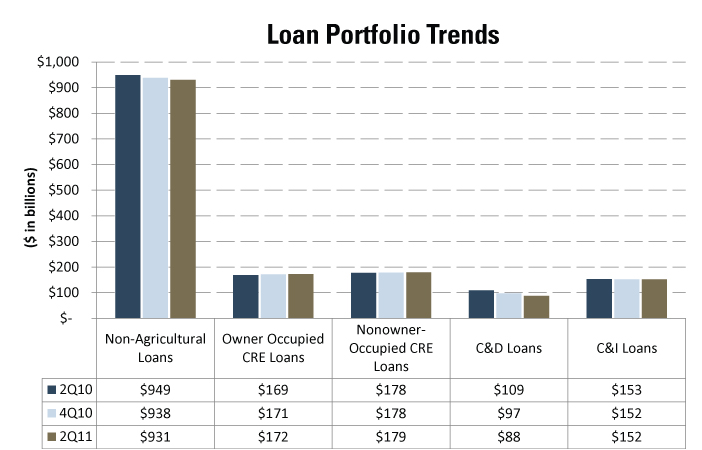

Balance Sheet

For a majority of the community banks in the analysis, loan growth has not yet resumed. As of June 30, 2011, 62% of community banks reported lower balances of non-agricultural loans, as compared to December 31, 2010 – a trend consistent with the 58% of banks that reported lower loan balances at year-end 2010 than at year-end 2009. The aggregate loans outstanding held by community banks declined by 0.79% between year-end 2010 and June 30, 2011. However, the contraction was not spread evenly throughout loan portfolios. Instead, construction and development loans continue to shrink, offsetting growth in commercial real estate (both owner and non-owner occupied) and commercial and industrial loans.

Figure Four

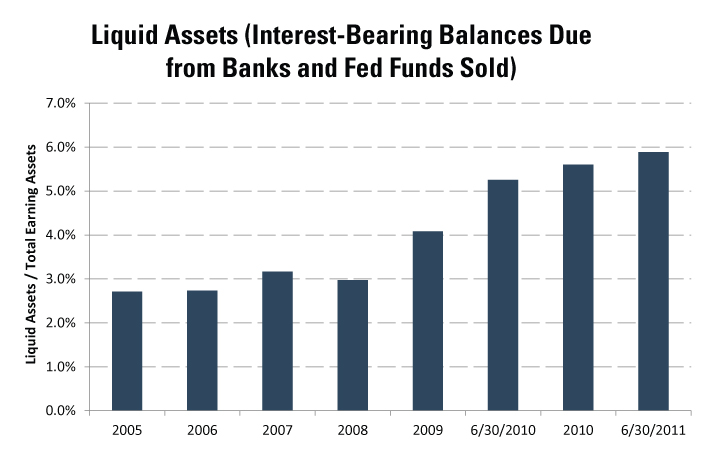

Liquidity continues to accumulate within the community banking industry, albeit at a somewhat slower pace than in recent years, as indicated in the following table showing the median ratio of liquid assets to total earning assets. Offsetting this increase, the median ratio of loans to earning assets declined from 74% at June 30, 2010 and December 31, 2010 to 71% at June 30, 2011.

Asset Quality

One notable trend in fiscal 2010 among community banks was the steady quarterly increase in non-performing assets, despite a gradually recovering economy. After reaching 3.78% in the first quarter of 2011, the median ratio of non-performing assets to loans and other real estate owned decreased by four basis points in the second quarter of 2011, marking the first decline in this ratio since the second quarter of 2006.

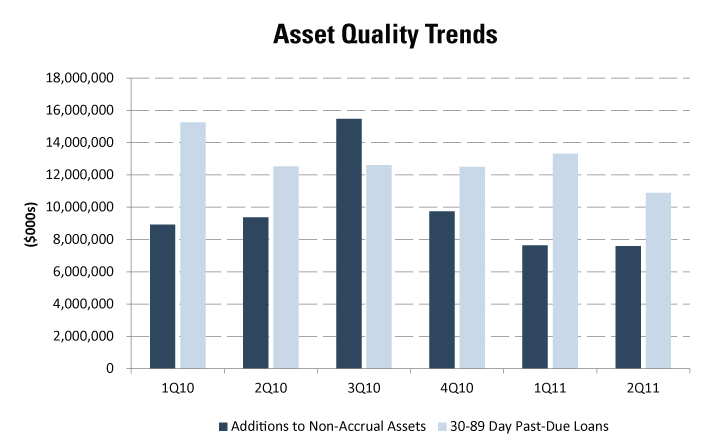

As further evidence of the gradual improvement in asset quality, new additions to non-accrual assets dropped below $8 billion (in aggregate for the 3,800 banks) in both the first and second quarters of 2011 – a level below any quarter in 2010. In addition, loans past-due 30-89 days, representing potential future non-accrual loans, fell to $10.9 billion at June 30, 2011, the lowest level since at least the first quarter of 2010.

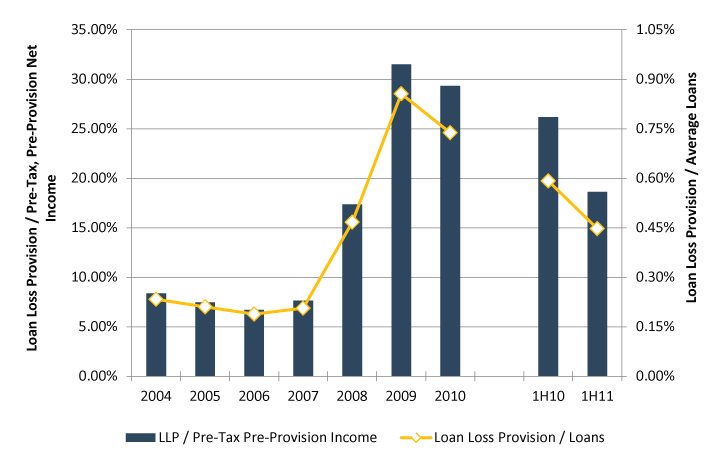

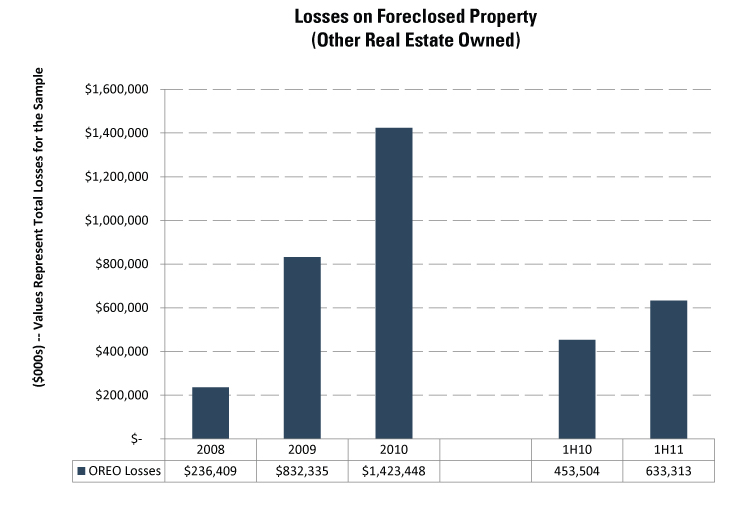

Similar to the trend reported by larger banks in their mid-year earnings releases, community banks continue to see reductions in loan loss provisions. The aggregate loan loss provision reported by the 3,800 banks in the data set declined by 32% in the first half of 2011, versus the same period in 2010. For the median bank, the annualized loan loss provision dropped to 0.45% of loans in the first half of 2011, as compared to 0.59% in the first half of 2010. To some degree, though, credit costs have shifted within the income statement from loan loss provisions to losses and other costs related to other real estate owned. In the first half of 2011, losses on sale of other real estate owned increased by 40% versus the first half of 2010.

For the second half of 2011, trends to monitor include:

- Whether the reduction in the median ratio of non-performing assets/loans and other real estate owned represents the beginning of a trend or a one-time occurrence

- The impact of the stock market declines in early August 2011, the U.S. sovereign debt credit rating downgrade, and the European debt crisis on community banks. While the direct impact may be muted, banks may not escape an indirect effect if macroeconomic conditions deteriorate further

- The levers available to banks to improve earnings, as the boost from lower loan provisions begins to wane. Also in this vein, the second half of 2011 will allow the first opportunity to assess the impact, if any, of the Durbin amendment on community banks

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, released August 15, 2011.

Bank Merger and Acquisition Review: A Look Back at 2010 and Look Forward to 2011

For several years now, industry experts have been predicting a wave of bank consolidation. The initial reasoning was that weaker banks would be absorbed by stronger banks, many against their will when faced with the choice of merger or failure. As time passed the industry realized that even the healthiest institutions were either unwilling or unable (sometimes both) to take on the debt, shareholder dilution, and asset quality problems that come along with an acquisition.

At present, the presumed M&A driver for the near-term is regulatory changes, which will place a substantial burden on institutions. The smaller the institution, the theory goes, the more onerous the burden and the more diminished the ability to absorb the associated costs. The only solution, many argue, is to grow organically (not easily done in the current environment) or find strategic combinations that will create a bank large enough to support the additional operating expense.

Is this wave of predicted merger activity finally coming to fruition? One might think so, based on the uptick in announced bank deals in 2010. According to SNL Financial, LLC there were 205 announced deals in 2010, compared to 175 announced in 2009. This does not include the 157 FDIC-assisted transactions which occurred during the year. Additionally, deal value was substantially higher in 2010, at $11.8 billion, compared to $2.0 billion in 2009. The increase in total deal value was supported by a few larger acquisitions, including BMO’s purchase of Marshall & Ilsley Corporation ($5.8 billion), Hancock Holding Company’s purchase of Whitney Holding Corporation ($1.8 billion), and First Niagara Financial Group’s purchase of NewAlliance Bancshares, Inc. ($1.5 billion).

However, the M&A story in 2010 lies within the realm of the community bank. As shown below, for deals in which pricing multiples and deal value are available (a total of 111 transactions), 84 transactions, or more than 75%, involved a seller with assets less than $500 million.

What is notable in the table above is that the size of the seller appears to be negatively correlated with the pricing multiples received, particularly on a book value basis.

The smallest banks were the only group which reported a median purchase price at a premium to book value, both reported and tangible. Of course, it is worth noting that the larger groups contain a fewer number of transactions, and perhaps reflect a more dire situation on the part of the seller, who presumably has little incentive to sell in the current pricing environment.

Cash remained king in 2010 as the most common form of transaction funding. Forty of the 111 transactions reporting multiples were all-cash acquisitions, followed closely by 38 which were some mixture of cash and other consideration (generally common stock). Capital contributions accounted for eighteen of the transactions and common stock was used as currency in six of the transactions. The remainder were unclassified or not reported.

The banking industry has always exhibited a proclivity to finance acquisitions using cash on hand. However, it is no surprise that buyers, who likely are facing their own problems with low stock valuations, are reluctant to dilute shareholders by using what many consider to be an undervalued asset to fund purchases. After all, pricing multiples in the public marketplace remain well off the highs of 2006 and 2007, when bank stocks commonly traded at price-to-earnings multiples approaching twenty times and book value multiples as high as three times. Additionally, with the universe of transactions focused on smaller institutions, many do not have publicly traded equity, and sellers often frown on accepting illiquid stock as transaction currency.

In terms of geography, there was a distinct relationship between the economic health of various regions and the volume of transaction activity. During 2010 the concentration of FDIC-assisted transactions (i.e., bank failures) centered around states with severely disrupted real estate markets, such as Florida (29 failures), Georgia (21 failures), Illinois (16 failures), California (12 failures), and Washington (11 failures). Perhaps not surprisingly, non-assisted transaction activity was highest in regions without a high level of bank failures, as shown in the table below (includes only those deals reporting pricing multiples).1

The next logical question is what will 2011 hold for bank M&A activity? While we do not have a perfectly clear crystal ball, here are a few things to consider:

- The new regulations that will come as a result of the Dodd-Frank Act, once they are written, will most likely hamper a bank’s ability to generate fee-based income, which is an increasingly large portion of the bottom line for most financial institutions.Many industry insiders believe there is a “magic” size that a bank will need to be in order to absorb the additional costs and lower revenues inflicted by the new regulations. Whether that number is $500 million or $1 billion in assets, popular figures at the moment, or some other amount, there will be a measurable number of banks that are below the threshold.While some may resist the urge to merge, and indeed some will face specific circumstances that allow them to survive despite their smaller size, there is certainly an impetus for mergers of equals and for smaller institutions to begin shopping themselves to the highest bidder.

- Because of increasing regulatory burdens, we have heard from life-long bankers on a number of occasions that they simply no longer enjoy what they are doing.Many, who are second and third generation bankers, have entertained the idea of selling the bank in order to avoid the extreme headache which comes along with increasing regulatory oversight. While these thoughts may be dampened somewhat when it comes time to put pen to contract, and particularly in light of the current pricing environment, it is a real trend that could lead to more institutions being marketed for sale in the next several years.

- While there may be more banks for sale and more incentive to merge, financing such purchases may be easier said than done.Capital remains difficult to come by for financial institutions, and both market and non-market forces are responsible culprits. First, regulators are requiring a higher capital cushion from banks, a requirement with which a large portion are not in compliance at present. It will take a number of years to build up adequate capital levels, particularly given that most increases in capital will likely have to come from retained earnings as investors remain hesitant to contribute additional capital to all but the healthiest banks. Secondly, the issuance of new trust preferred securities, which previously were a relatively cheap and accessible source of capital for financial institutions, has been virtually eliminated by the Collins Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, which prohibits this form of capital for larger institutions and only grandfathers in existing trust preferred securities for smaller banks.

- FDIC-assisted transactions are likely to continue at a rapid clip, as the problem bank list stood at 884 for the fourth quarter of 2010, compared to 702 banks at year-end 2009 leading into a year where we saw 157 bank failures.For banks that are actively pursuing a strategy involving growth by acquisition, there is little incentive to pay full market price for a healthy institution when the failed banks marketed by the FDIC are available at such extensive discounts, even despite the associated bidding, asset quality, and other problems related to purchasing a failed bank.

- While outside investors have, up to this point, been effectively shut out of the market for whole-bank purchases, the tide seems to be turning.A number of private equity acquirers participated in FDIC-assisted transactions in 2010, which previously had generally been frowned upon by the FDIC. Additionally, private equity firms have recently been allowed to file shelf charters which allow them to quickly form a bank holding company for purposes of acquiring an existing institution. Purchases of banks and bank holding companies must to be approved by regulators, who up to this point have shown a preference that the acquirer be another bank. An additional subset of buyers in the market can only serve to increase demand, transaction activity and, most likely, pricing multiples.

Will 2011 be the year of the bank merger? Signs remain mixed, but it appears conditions are favorable at the very least for an increase in merger activity. Then again, we have definitely heard that before.

ENDNOTES

1 The regions include the following states:

- Atlantic Coast – Delaware, Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Washington, D.C.

- Midwest – Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Wisconsin

- Northeast – Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont

- Southeast – Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Tennessee

- West – Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch 2011-03, released March 2011.

Accounting Considerations in the Acquisition of a Failed Bank

After completing an FDIC-assisted transaction, the acquirer faces the task of accounting for the transaction in accordance with FASB ASC 805, Business Combinations (formerly SFAS141R). ASC 805 requires the acquirer to record purchased loans at their fair value, or the amount that would be received upon the sale of the subject loans in a transaction between market participants. Given the credit deterioration evident in the loan portfolios of most failed banks, the book values and fair values of acquired loans may diverge to a material degree.

Deposit assumption transactions generally present no complex accounting or valuation issues. Demand and savings accounts are recorded at their book values, which equal fair value. The acquired time deposit portfolio may require a determination of fair value. Unlike a non-assisted transaction, however, acquirers in assisted transactions have the right to adjust the rates on time deposit accounts immediately upon the acquisition. These rate adjustments, along with any attendant deposit run-off, may require consideration in the fair value analysis. Lastly, although not recorded in some transactions, the acquirer may recognize a core deposit intangible asset. While the acquirer may agree upon a deposit premium with the FDIC (or agree that a premium is not appropriate), this premium may not be determinative of fair value, as the intent of fair value is to determine a price in an “orderly” transaction. An FDIC-assisted transaction may not meet the definition of an “orderly” transaction for purposes of determining fair value.

Assisted transactions whereby the acquirer obtains the failed bank’s assets, including its loans, along with a loss-sharing agreement present a much more complicated series of valuation and accounting issues. The valuation and accounting issues can be grouped in two primary categories:

- Issues that arise upon recording the transaction at the acquisition date; and,

- Issues that arise in the post-acquisition accounting for the acquired assets.

Mercer Capital reviewed SEC filings of banks participating in loss-share transactions. From this review, there appears to be some diversity of practice as to the accounting for loss-share transactions. The following discussion, therefore, is general in nature. Banks participating in loss-share transactions are advised to seek guidance from their accounting firms as to the valuation and accounting issues raised by the transactions.

Acquisition Date Issues

At the acquisition date, an acquirer would need to determine the fair value of the following assets:

- The loan portfolio, inclusive of consideration of the credit risk associated with the portfolio;

- The loss-share agreement, for which the fair value is tied to the projected losses covered by the FDIC;

- The core deposit intangible asset related to the assumed deposits; and,

- The time deposit portfolio assumed in the transaction.

Based on the preceding determinations of fair value, the acquirer would then calculate the amount of goodwill or negative goodwill. While goodwill is recorded as an asset on the balance sheet, negative goodwill results in a gain to the acquirer in the period surrounding the acquisition (included in non-interest income).

To demonstrate the preceding accounting and valuation issues, consider the following hypothetical transaction:

- An acquirer enters into a loss-share agreement with the FDIC regarding a failed bank with assets at book value of $1,000 and liabilities of $1,000. The acquirer agrees to purchase these assets for a discount of 15%.

- The acquired loan portfolio has a stated interest rate of 5% and amortizes over a three year term to maturity.

- After reviewing the loans, the acquirer estimates that loan losses of 10% on the remaining outstanding principal balance will occur in each of the three years remaining to maturity of the loans.

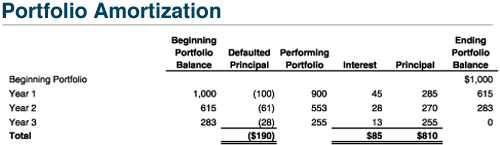

Based on the preceding, Figure One amortizes the acquired loans:

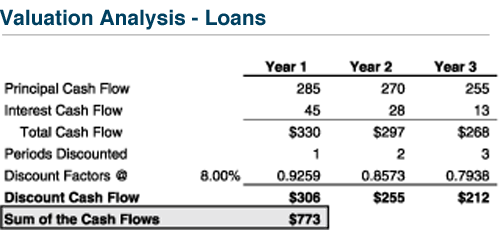

After determining the expected cash flows from the portfolio, the acquirer can then determine the fair value of the acquired loans. Because credit spreads have widened since origination of the loans, and to reflect the risk of adverse deterioration in default rates, the acquirer estimates that an 8% discount rate is appropriate.

Figure Two then illustrates the determination of fair value of the acquired loan portfolio:

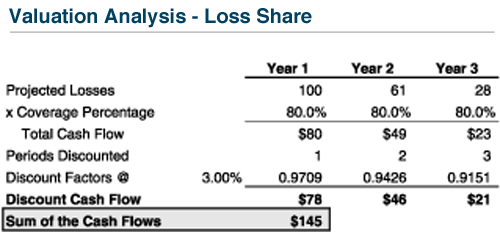

The acquirer would thus record the acquired loan portfolio at its fair value of $773. Next, the acquirer would determine the fair value of the loss-share agreement, based on the projected loan losses and the loss coverage percentage agreed upon with the FDIC. The valuation of the loss-share agreement generally assumes a lower discount rate than the determination of fair value of the loan portfolio, given the relative assurance of collection of amounts due under the loss-share agreement from the FDIC.

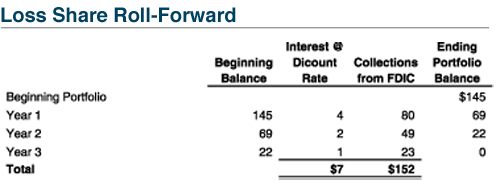

Figure Three shows this calculation.

Based on the preceding determinations of fair value, and assuming the fair value of the liabilities equals book value, Figure Four indicates the assets and liabilities acquired in the transaction.

In the transaction, the acquirer received $1,068 of assets at fair value and assumed $1,000 of liabilities. To balance its books, therefore, the acquirer would need to need to record “negative goodwill” of $68; however, negative goodwill is not recorded as a “negative” asset. Instead, ASC 805 indicates that the acquirer should record a gain equal to the amount of negative goodwill.

Post-Acquisition Date Issues

In many instances, due to the volume of problem assets, the magnitude of the fair value adjustments to the loan portfolio, and the need to track the loss-share asset, the post-acquisition accounting for the acquired loans is more complicated than the acquisition-date accounting. The primary ongoing accounting issues faced by the acquiring bank include the following:

- Estimating the accretion of the loan portfolio discount and the carrying value of the loan portfolio; and,

- Estimating the accretion of the loss share agreement and the carrying value of the loss-share agreement.

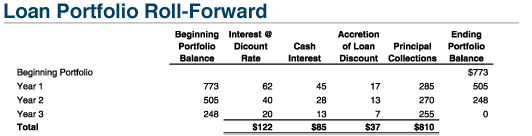

Figure Five rolls the loan portfolio balance forward from the acquisition date starting with the beginning fair value of the portfolio ($773).

In each period, the bank collects principal and interest payments on the portfolio, per the amortization of the portfolio in Figure One. In addition, the bank determined the fair value of the portfolio based on the return required by market participants at the valuation date (8%), which exceeded the stated note rate on the portfolio (5%). This disparity results in an additional loan discount accretion.

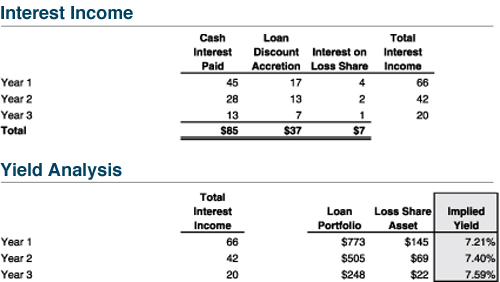

For example, in year 1, at an 8% interest rate, the portfolio would yield income of $62 ($773 x 8%). However, the bank collects interest of only $45 from borrowers. The $17 difference between the market yield and the note rate is accreted into income by the acquiring bank. The ending portfolio balance therefore equals the beginning portfolio balance ($773), minus principal collections ($285), plus the discount accretion ($17). Figure Six shows the roll-forward of the loss-share asset.

As indicated in Figure Six, the loss-share asset declines as the FDIC remits payments against covered losses. In addition, the fair value of the loss-share agreement was determined based upon an assumed 3% discount rate. As for the loans, this 3% return is accreted into income. Figure Seven summarizes the interest collected and accreted on the loan portfolio and loss-share asset.

In sum, the acquiring bank’s interest income from the acquired loans would consist of three sources – the interest paid by the borrowers, the discount accretion on the loans, and the accretion of interest on the loss-share agreement. Overall, the acquiring bank would earn an effective yield of approximately 7.25% to 7.50% on the assets acquired, versus the actual note rate of 5%.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis, while still complex, is greatly simplified from real world practice. In reality, acquirers are faced with many challenging issues, such as:

- How should the acquirer consider credit deterioration in the determination of the fair value of the loan portfolio, particularly when weak underwriting or servicing lead to great uncertainty as to future credit losses?

- What adjustments are necessary when the actual cash flows from the portfolio differ from the projected cash flows? The preceding analysis made the greatly simplifying assumption that cash flows occur as originally anticipated. In reality, as actual cash flows differ from expected cash flows, the acquirer may need to adjust the loan discount accretion, the loss-share asset, and perhaps even establish a loan loss reserve when anticipated cash flows are lower than initially expected.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Added (TM) Vol. 22, No. 1, May 2010

Mercer Capital Study Finds Community Banks Dominated by Recession in 2008

As the world hoped to return to normalcy after a turbulent 2007, 2008 proved to be a worse year for bankers. A credit crunch and housing collapse maintained the downward pressure on stock prices that began in 2007. 2008 saw the closure of 25 banks nationwide, and the overall banking industry has struggled with deteriorating asset quality and liquidity concerns. In order to gauge the impact of the 2008 financial institution market trends on smaller institutions, Mercer Capital conducted a study of two asset size based bank indices: banks with assets between $500 million and $1 billion (referred to hereafter as the “Small Community Bank Group”) and banks with assets between $1 billion and $5 billion (the “Large Community Bank Group”).

The banking industry made headlines throughout the second half of 2008. The struggles of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae necessitated nationalization of the two government-sponsored enterprises, and the failures of IndyMac Bank and Washington Mutual Bank fueled the erosion of confidence in the banking industry. Furthermore, the acquisitions of Merrill Lynch by Bank of America and Wachovia by Wells Fargo signaled consolidation in the banking industry in order to survive the economic uncertainty.

In an attempt to provide assistance to the banking industry, the government developed several programs to improve banks’ asset quality and capital positions. Under the Emergency Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, the Troubled Asset Relief Program (“TARP”) was developed with the intention of cleaning up the balance sheets of banks by removing troubled assets from the books. Because pricing the troubled assets was difficult given economic uncertainty, the initial structure of the TARP was abandoned shortly after the program was established. Instead, the Capital Purchase Program under the TARP attempted to provide stability for financial institutions by providing capital injections.

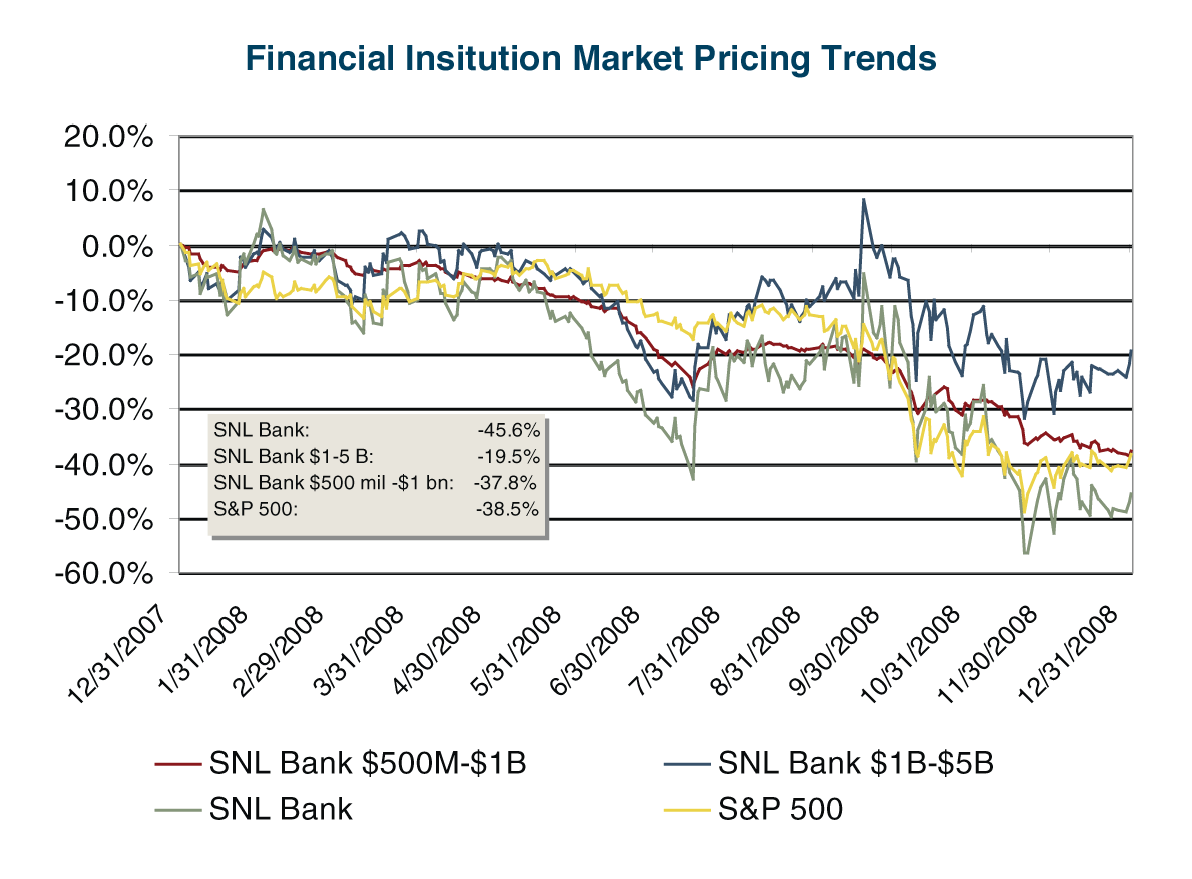

Figure One depicts market pricing trends of financial institutions during 2008. As shown, the Large Community Bank Group saw a price decline of 19.5%, outperforming the overall market, as measured by the performance of the S&P 500, as well as the banking industry, as measured by the SNL Bank Index. For comparison purposes, the SNL Bank Index saw a 45.6% decline in price due primarily to the decline in value of a number of large institutions, and the S&P 500 saw a 38.5% decline in 2008. The Small Community Bank Group observed a decline of 37.8%, reflecting their poorest performance in the last decade.

In order to attempt to isolate the driving trends behind the market performance of these institutions in 2008, we stratified the banks in each group based on TARP participation, asset quality metrics, loan portfolio concentrations, and location. Banks with unavailable financial data were excluded from our stratification, and the resulting analysis included 160 banks in the Large Community Bank Group and 84 banks in the Small Community Bank Group. The following discussion summarizes our findings.

- TARP Participation. As TARP regulations continue to unfold, our study revealed several interesting trends in bank stock pricing among participants in the program. More banks in the Large Community Bank Group elected to participate in the TARP program than the Small Community Bank Group (58.8% compared to 42.9%). For the Large Community Bank Group, participating banks saw a median price decline of 31.9% compared to declines of 34.8% for banks that opted not to apply and 17.5% for banks that declined the funds after being approved. Banks that applied but had not been approved at the time of our analysis saw a median price decline of 76.3%. For the Small Community Bank Group, participating banks also had a larger decline (44.9%) than those that were approved but had not accepted the funds (23.3% decline) as well as banks that opted not to apply (29.4% decline). Banks that applied but had not yet been approved for TARP experienced a 64.3% decline in the median price.

- Asset Quality. 2008 highlighted the importance of strong asset quality in a weak economy. In the Large Community Bank Group, banks with strong asset quality (non-performing assets measuring less than 2.00% of leans plus OREO) experienced a median price decline of 3.9%. On the other hand, those with weak asset quality (non-performing assets measuring greater than 2.00% of leans plus OREO) experienced a median price decline of 51.5% over the same period. In the Small Community Bank Group, banks with strong asset quality (31.1% decline) outperformed those with weak credit quality (51.3% decline). Although most banks experienced stock declines, asset quality did affect the banks’ stock performance relative to the banking industry. For the Large Community Bank Group, 60% of banks with weak asset quality were outperformed by the SNL Bank index, compared to 14% of banks with strong asset quality. The Small Community Bank Group exhibited similar results, as 59% of banks with weak asset quality underperformed the SNL Bank index while only 13% of banks with strong asset quality were outperformed by the SNL Bank index.

- Construction and Development Loans. With aversion to risk among the most pressing issues in 2008, banks increased their standards for loans among the economic turmoil as loan losses continued to rise. The deterioration of the housing market continued to generate problems for construction and development (C&D) loans, in particular. The number of banks with high C&D concentrations (more than 40% of the loan portfolio) is limited due to data constraints as well as changes in loan portfolio composition during 2008 and meaningful comparisons were available only for the larger community banks. Six banks in the Large Community Bank Group were identified as having high C&D concentrations. The median price decline for these banks was 75.6%, compared to 29.8% for those banks with lower C&D loan concentrations.

- Commercial Real Estate Loans. Much like C&D loans, commercial real estate loans continued to generate high loan losses due to spreading real estate problems. Again, data for banks with high CRE concentrations is limited and meaningful comparisons were available only for the larger community banks. Of the Larger Community Bank Group, nine of the banks considered in this analysis reported commercial real estate loans comprising more than 50% of their entire loan portfolios. These banks experienced a median price decline of 49.9%, compared to the 30.2% decline for banks with lower CRE concentrations.

- Location. Location proved to be less important in 2008 than in 2007 as the economy as a whole was affected with the gloom of a recession. Although the hardships could be felt nationwide, the identified high-risk locations (California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, and Nevada) continued to experience higher declines in stock prices than the broader asset-size groups. For the larger banks, those in high-risk locations had a 49.1% decline as compared to a 34.3% decline for banks overall within the asset size group. For the smaller banks, those in high-risk locations experienced a 61.2% decline in price compared to the median price decline of 42.3% for all banks within the asset size group.Looking forward, 2009 could prove to be another difficult year for banks. Within the first four months of 2009, 29 banks failed, exceeding the number of bank failures during the full fiscal year 2008. As evidenced by early 2009 data, market pricing for financial institutions has declined further and exhibited greater volatility due to significant uncertainty regarding banks’ solvency and the government’s efforts to support financial institutions and the credit markets. By March 6, 2009 the SNL Bank Index hit a low, with a 59.6% decline from the beginning of the year. By April 30, the SNL Bank Index had increased 91.1% from March 6, exhibiting a total decline of 22.8% from the beginning of the year.

Given market volatility and uncertainty about the effects of new regulations and government support, investors have limited confidence in the overall market. The government is continually amending the TARP regulations and has begun performing stress tests on some of the largest financial institutions to examine banks’ ability to cope with various changes in the economy and try to improve capital positions. As the events of 2009 unfold in accordance with government programs and regulations as well as continued consolidation, the banking industry hopes for improved performance in the second half of 2009.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, Special Edition, May 19, 2009.

S Corporation Banks Beware

While most banks and their directors are generally aware of the tax benefits of an S election, there are some potential disadvantages. One disadvantage is the potential for S elections to encounter additional volatility to the equity account and lower capital ratios relative to C corporations when losses are incurred (all else equal).

When banks are profitable, the impact of the tax election on equity for S and C corporation banks is relatively muted as both pay out a portion of earnings to cover taxes either in the form of a direct payment of the federal tax liability as a C corporation or in the form of a cash distribution to shareholders to cover their portion of the tax liability as an S corporation. However, S corporations are typically limited relative to C corporations in their ability to recognize certain tax benefits when losses occur. The equity accounts of most C corporations benefit from the ability to recognize tax loss carrybacks and deferred tax assets following the occurrence of losses, which serve to soften the direct impact of the loss on capital. S corporations are generally precluded from any tax benefit after the recognition of losses and the resulting loss is directly deducted from equity. A few nasty quirks of book and tax income can make the situation even worse for shareholders and the S corporation bank.

To help illustrate the point further, consider the following example which details how losses realized as an S corporation can flow directly through to equity without the tax benefit recognized by a C corporation. As detailed below, the capital account of the S corporation was impacted more adversely following the recognition of losses than the C corporation (all else equal).

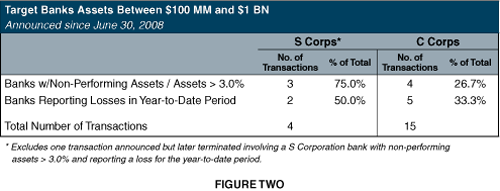

In a recent survey of bank transaction activity nationwide conducted by Mercer Capital, we noticed some evidence of this disadvantage surfacing among S corporation banks. Of transactions (whole bank sales) involving target banks with assets between $100 million and $1 billion announced since June 30, 2008, the majority of S corporation banks sold were distressed, defined as either having non-performing assets as a percentage of assets greater than 3.0% (three out of four transactions involving S corporation targets) or reporting a loss in the most recent year-to-date period (two out of four transactions involving S corporation targets). This trend is illustrated more fully in the chart below and is notable especially when compared to transaction activity of C corporations over this period.

We found some additional evidence that S corporation banks may be experiencing the detrimental impact of additional capital volatility in a review of bank failures. Of 8 total S corporation bank failures since 1998, five have occurred since January 1, 2008, with three occurring since December 1, 2008.

While it is too early to tell whether this evidence of increased transaction activity and failures among distressed S corporations is purely a coincidence or early indications of an emerging trend of capital volatility for S corporation banks, this analysis prompted a number of questions:

- Should a conversion to a C corporation be considered by an S corporation prior to recognizing losses?

- Should a conversion to a C corporation be considered even if no immediate losses are expected as a matter of conservatism?

- Should the exploration of acquisition possibilities by S corporations be accelerated prior to recognizing losses so that a C corporation buyer could recognize any tax benefits potentially unavailable to the S corporation or its shareholders?

- Should S corporations be managed more conservatively than C corporations given the added potential for volatility in the capital account?

- Should an increase in merger and recapitalization activity, bank failures, or conversion back to C corporations among troubled S corporation banks be expected for the remainder of 2009 and beyond?

- Do the shareholder limitations of S corporations limit their ability to raise capital, thereby forcing a distressed S corporation bank to pursue merger partners when substantial losses arise?

If your bank is dealing with any of these issues, feel free to give us a call to discuss the situation confidentially.

Sub-Chapter S Election for Banks

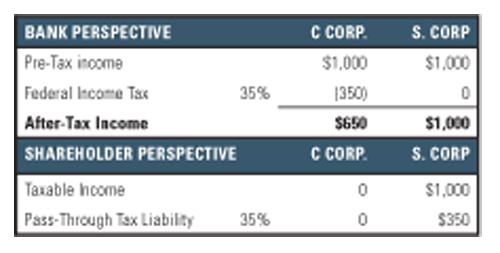

An S “election” represents a change in a bank’s tax status. When a bank “elects” S corporation status, it opts to become taxed under Subchapter S of the U.S. Tax Code, instead of Subchapter C of the Code. When taxed as a C corporation, the bank pays federal income taxes on its taxable income. By making the S election, the bank no longer pays federal income tax itself. The tax liability does not disappear altogether, though. Instead, the tax liability “passes through” to the shareholders. This means that the bank’s tax liability becomes the obligation of the bank’s shareholders. While no guarantees generally exist, the bank will ordinarily intend to distribute enough cash to the shareholders to enable them to satisfy the tax liability.

An Example

The following table shows what happens when a bank makes an S election. In the table, the bank no longer incurs any federal tax liability following the S election. However, the $350 tax obligation simply “passes through” to the shareholders.

S Election Benefits

In the preceding table, the bank’s pre-tax income generated a $350 tax obligation, regardless of whether the bank was taxed as a C or S corporation. In the C corporation scenario, the bank directly paid the tax obligation to the government; in the S corporation alternative, the shareholders paid the taxes due on the bank’s earnings. Since the taxes due remain constant at $350 regardless of whether the bank elects

S corporation status or not, what incentive exists for banks to elect S corporation status?

The S election creates two primary tax advantages relative to C corporations:

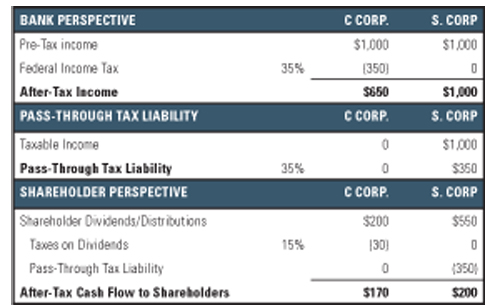

- Dividends paid by a C corporation are taxable to the shareholders. However, shareholders in an S corporation incur no tax liability beyond the taxes on their pro rata share of the S corporation’s taxable income.

- In a C corporation, a shareholder’s tax basis generally remains constant during the period the shareholder holds the investment. S corporation shareholders, however, benefit because their tax basis increases to the extent that the bank retains earnings. This may reduce the capital gains taxes payable when a shareholder sells any shares of the bank’s stock.

The best way to illustrate tax advantage #1 is with an example.

In the C corporation scenario, the bank pays $200 of dividends to shareholders. After the shareholders pay taxes on these dividends (at a 15% tax rate on dividends), the shareholders will have after-tax cash flow of $170 from their investment. Assume, instead, that the bank elects S corporation status. In this case, the shareholders owe taxes of $350 (35% of the bank’s $1,000 pre-tax income), but the bank makes distributions of $550. This leaves the shareholders with $200 of after-tax cash flow. No further taxes are owed on the $200. In fact, for any amount of distributions between zero and $1,000 (the bank’s pre-tax earnings), the shareholders will generally face tax liability of $350. By electing S corporation status, therefore, shareholders increase their after-tax cash flow from $170 to $200, an 18% increase.

Disadvantages of an S Election

Given the aforementioned tax benefits, why would every bank not elect S corporation status? Several potential disadvantages of the election exist:

- Limitations exist on the type and number of shareholders that may hold stock in an S corporation. If the bank currently has too many shareholders, a transaction that “squeezes out” certain shareholders may be necessary in order to make the election. This gives rise to the risk that shareholders can sue, demanding a greater amount for their shares than offered by the bank.

- S elections can increase the risk associated with an investment in the bank. For instance, assume that the bank reports a pre-tax loss of $1,000. If the bank is taxed as a C corporation, it will generally record a tax benefit related to the loss, and, the bank’s retained earnings will fall by only $650 (the $1,000 pre-tax loss minus a $350 tax benefit, assuming a 35% tax rate). However, if the bank is taxed as an S corporation, it will record no tax benefit in its books, and the entire $1,000 pre-tax loss will flow through retained earnings. Thus, in the event a loss occurs, the S corporation’s capital account will be $350 less than the capital account of a similarly situated C corporation (which is equal to the amount of the tax benefit recorded by the C corporation). In the event that the losses are material to the bank, the adverse capital treatment of an S corporation can prove material.In addition to the preceding effect on capital, it is entirely possible for the S corporation bank to have taxable income (thereby creating a tax obligation on the part of the bank’s shareholders) but a net loss for book purposes. This could occur because, for instance, loan loss provisions in excess of actual loan losses may not be tax deductible. This situation could create a highly negative outcome for the bank’s shareholders – the shareholders may face a personal tax liability but the bank’s capital position may limit its ability to make distributions to the shareholders.

To minimize these risks, the board of directors and management may adopt a more conservative management style for the S corporation bank than the C corporation bank. For instance, higher capital ratios may be desirable. In addition, the bank may adopt more strict underwriting requirements or maintain a lower loan/deposit ratio to reduce the risk of losses.

- The advantages of S elections depend to some degree on the relationship between corporate, personal, and dividend tax rates. In the future, changes in the relationship between these tax rates could make S elections less desirable. For instance, a reduction in the C corporation tax rate, while the personal tax rate increases, could reduce or eliminate the benefits associated with an S election.

- Certain one-time costs associated with an S election exist. For example, a bank must generally write-off its deferred tax asset upon the S election. This write-off will reduce earnings and capital in the year it occurs.

- The bank may still face federal income taxes on certain assets sold within ten years of the S election. This is referred to as the “built-in gains” tax.

Conclusion

S corporation elections may be an attractive alternative for banks, but a careful examination of the advantages and disadvantages is necessary. Banks with relatively low balance sheet growth and high profitability often make the best candidates for S elections, because these banks have the capacity to distribute a large portion of their earnings. On the other hand, an S election would be less beneficial for other types of banks. For instance, banks that intend to pursue acquisitions or that have potentially volatile earnings may be better served by remaining C corporations.

If your bank does elect to make an S election, it is typically more complicated than simply “checking a box” on a tax filing. Instead, a number of professionals may need to be involved to ensure the bank’s goals are achieved:

- The bank’s corporate attorney would be involved throughout the process. The attorney would assist in handling any shareholders that do not qualify as S corporation shareholders (such as negotiating a voluntary repurchase or structuring an involuntary transaction), drafting any necessary proxy statements distributed to the shareholders, and creating the shareholder agreement that restricts the sale of the bank’s shares to preserve the S election.

- The bank’s tax accountant or tax attorney would also have an important role. This includes analyzing the shareholder base to determine which shareholders may not qualify as S corporation shareholders and considering any specific tax issues relevant to a particular bank.

- A business appraiser has several roles. First, the bank may require an appraisal of its stock prior to the S election for purposes of the built-in gains tax that may arise if the bank is eventually sold. Second, appraisals are often necessary when repurchasing stock from non-qualifying shareholders, whether the transaction is voluntary or involuntary. Third, a fairness opinion may be needed to determine the fairness to the bank’s shareholders or one specific group of shareholders such as the ESOP of the “squeeze out” transaction.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Matters™ 2008-08, published August 31, 2008

Capital Conundrums

Capital raising efforts among financial institutions began in earnest in late 2007, primarily among money center banks and investment banks suffering under the weight of mark-to-market adjustments on various asset types. Banks with fewer assets marked to fair value through the income statement largely maintained sufficient capital to manage the initial wave of industry problems. However, the capital pressures intensified in 2008 as past-due levels and losses increased across a spectrum of loans tied to real estate, causing a number of banks to reassess their capital positions and, in some cases, to capitulate under the weight of the external environment and seek out additional capital.

This article provides a summary of capital raising transactions that have occurred in 2008 and offers insight into the financial considerations present in evaluating each capital alternative. These considerations are relevant whether a bank is in the position of raising capital to buttress the balance sheet or, alternatively, has an opportunity to make an investment in another bank facing a capital shortfall.

Common Stock

The surest way to shore-up capital ratios is through the issuance of common stock, which places no pressure on the company’s cash flow if no dividends are declared. The primary disadvantage of common stock offerings is the dilution that current shareholders may experience to their ownership positions and future earnings per share.

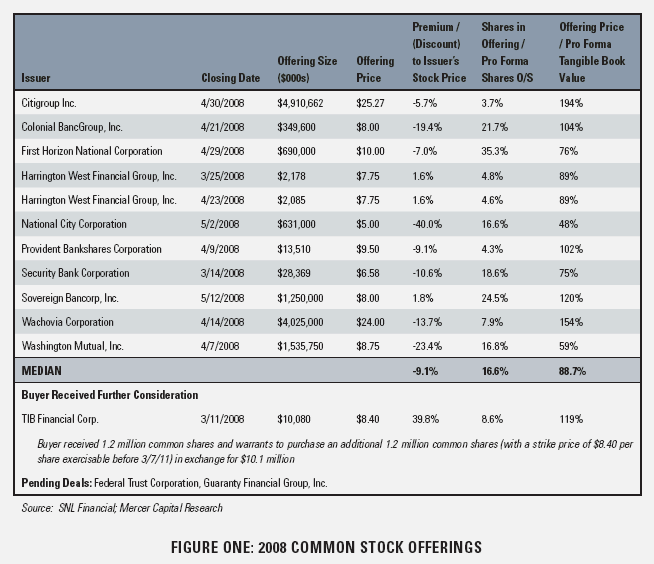

Figure One indicates recent common stock offerings. Most of the issuances have occurred at discounts to the issuer’s stock price prior to the transaction. In one-half of the issuances, the offering price for the common stock was less than pro forma tangible book value per share (existing tangible book value, plus the equity raised in the offering). One recent article noted that investors were potentially willing to purchase stock at tangible book value per share, as adjusted to reflect the investors’ estimate of expected losses in the loan portfolio.

In considering a common stock issuance, important questions for community banks to consider include:

- How should the transaction be structured? Should the bank conduct a subscription rights offering to existing shareholders? Should the bank attempt to sell stock to a small number of new investors who may bring additional expertise to the bank?

- What perquisites of control, such as board seats, should the new investors possess?

- What share price balances the need to raise capital with the goal of minimizing dilution to the existing shareholders? In setting the price, how does the bank bridge any gap between the investor’s assumptions about potential losses inherent in the portfolio with bank management’s estimates of such losses?

- Should other incentives, such as warrants, be included in the “package” offered to investors?

Preferred Stock

Depending on its structure, preferred stock can bear a resemblance to either long-term debt or equity. In its simplest form, “straight” preferred stock economically resembles long-term debt with either fixed or floating rate payments. Convertible preferred stock is a hybrid instrument that combines elements of both debt and equity. Generally, convertible preferred stock has a lower dividend rate than straight preferred stock, but a higher yield than common stock. To compensate investors for accepting the lower current return, the investors receive the right to participate in the appreciation of the common stock. Further, preferred stock dividends can be either cumulative (meaning that dividends are accrued in the intent of paying such dividends later) or noncumulative.

From a bank’s perspective the advantages of preferred stock include:

- Tier 1 capital treatment of the proceeds. No formal limits exist on the amount of non-cumulative preferred stock that a bank may include in Tier 1 capital, although certain informal limits exist on a bank’s reliance on non-voting equity, such as preferred stock. Cumulative preferred stock is includible in Tier 1 capital, subject to certain limits;

- For straight preferred stock, the avoidance of dilution caused by issuing common stock; and,

- For convertible preferred stock, a potentially lower dividend rate than obtainable by issuing straight preferred stock or subordinated debt.

Potential disadvantages from a bank’s perspective include:

- The cash flow requirements to service the dividend payments; and,

- The lack of tax deductibility of the dividend payments.

From an investor’s perspective, preferred stock can be an attractive alternative to common stock. For convertible preferred stock, the investor may receive a dividend in excess of the common stock’s dividend, plus the right to enjoy appreciation in the underlying common stock. Thus, the higher dividend protects the investor’s downside (to the extent the issuer actually pays the dividend). Further, if the investor is a corporation, the tax deduction for dividends received may be available.

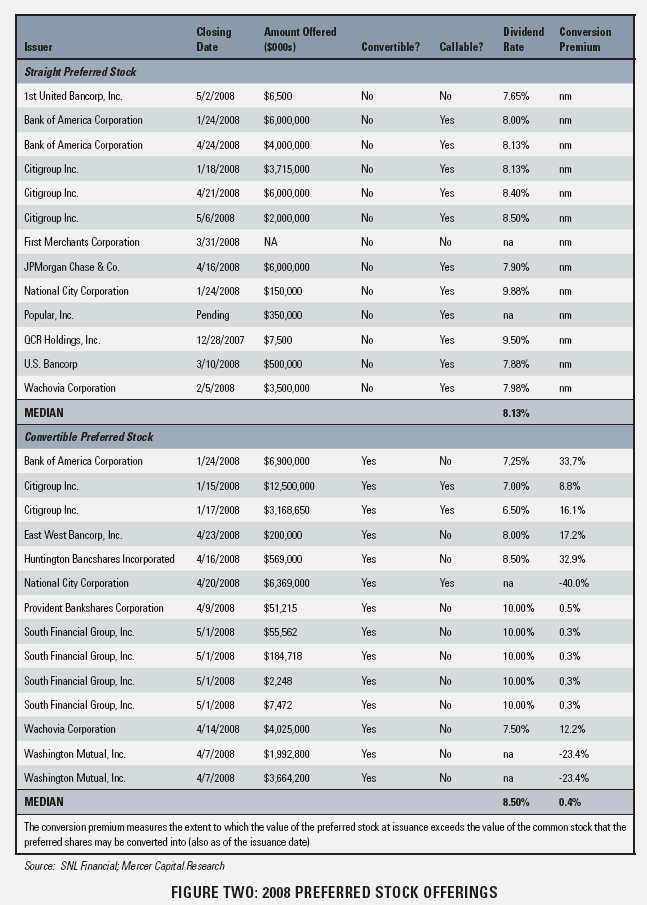

Preferred stocks have been a popular capital raising tool in the present environment, owing to their flexibility and the downside protection afforded to investors. Figure Two indicates issuances announced during 2008.

When structuring a preferred stock issuance, important considerations include:

- What is the appropriate dividend rate? This depends, in part, on the type of preferred stock (straight or convertible). In addition, the perceived credit quality of the issuer is of paramount importance – compare the 9.88% rate on National City’s issuance to the 7.88% rate on U.S. Bancorp’s offering.Ordinarily, dividend rates on convertible preferred stocks are lower than straight issuances. While this is true for individual issuers (note, for instance, the difference in the dividend rates on Citigroup’s straight and convertible issuances), it is not true for the group of recent issuances as a whole. Several convertible issues contain dividend rates of 10% – higher than any straight issuances. This likely reflects the perceived financial condition of the issuers and the resulting difficulty in accessing the capital markets.

- For convertible issues, what is the appropriate conversion premium? At the date the preferred stock is issued, the conversion premium measures the extent to which the issuance price of the preferred stock (generally its par value) exceeds the value of the common stock into which the investor may convert the preferred shares. For instance, consider a preferred stock with a par value of $1,000 that can be converted into 20 shares. This implies that the conversion price is $50 ($1,000 / 20 shares). If the value of the common stock on that date was $50 as well, then the conversion premium is 0%. Generally, conversion premiums are greater than 0%, meaning that the common stock must appreciate before conversion becomes financially attractive.Issuing banks prefer higher conversion premiums, because fewer shares will be issued upon conversion. Continuing the preceding example, if the conversion premium is 20%, the conversion price would be $60 ($50 common stock price x 1.20). Then, upon conversion, the bank would issue only 16.7 shares ($1,000 par value / $60 conversion price). Conversely, investors prefer lower conversion premiums.

From an issuer’s perspective, the most unattractive terms include a high dividend rate and a low conversion premium. As an example, consider South Financial Group’s May offering of 10% preferred stock with a 0.3% conversion premium.

- Should the preferred stock investors receive voting rights? Of the issues analyzed, only the National City issuance granted voting rights to investors.

- Are the dividends cumulative? This affects the capital treatment of the proceeds, as well as the potential return required by an investor.

- Do the terms of the issuance meet applicable regulatory guidance for consideration in Tier 1 capital? Regulatory capital guidance contains a number of considerations that can affect the capital treatment of the offering. For instance, structures that create an incentive for the bank to redeem the preferred stock for cash, particularly in times of financial distress, may not be includible in capital.

Trust Preferred Securities

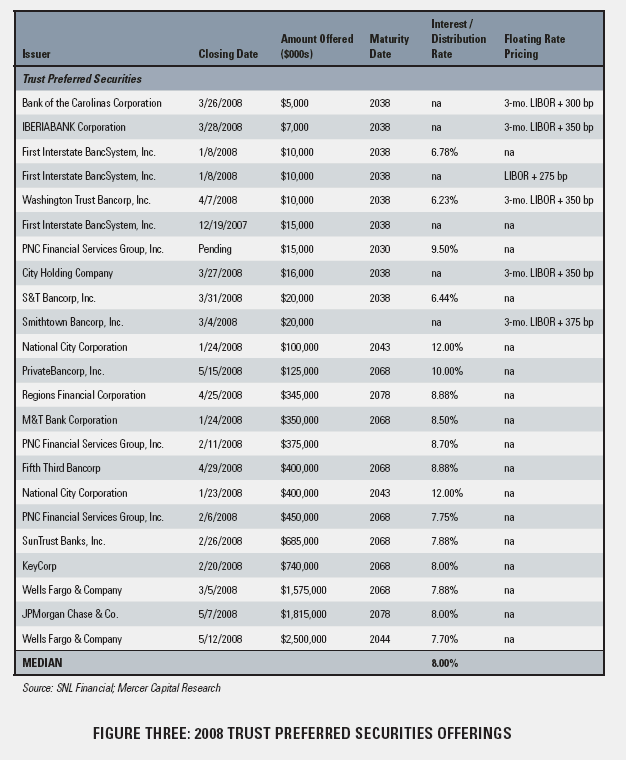

Trust preferred securities are a hybrid instrument, combining the tax treatment of debt and the Tier 1 capital treatment of equity. From a bank’s perspective, the favorable after-tax cost of capital represents one of the primary advantages. Prior to late 2007, another significant advantage of trust preferred securities was that community banks could easily access the capital markets by participating in one of the pooled offerings underwritten by investment banks. As conditions in the credit markets deteriorated, this advantage disappeared, as the pooled offerings have largely vanished from the marketplace, although they may eventually return if investor demand improves.

Figure Three indicates data on trust preferred securities offerings announced in 2008 by publicly traded banks. While pooled offerings have not occurred in 2008, several smaller publicly traded banks have placed trust preferred securities with institutional investors. The pricing in these offerings has increased since the last pooled offerings, which often contained spreads in the range of 150 basis points over LIBOR. The variable rate offerings indicated in the table contain spreads in the range of 350 basis points over LIBOR.

While the availability of trust preferred securities through pooled offerings is currently uncertain, other investors may exist. Alternatively, banks can consider issuing trust preferred securities to local investors or shareholders. Although this type of offering may require more time and professional fees than a pooled offering, the bank will still enjoy the significant tax and capital benefits of trust preferred securities. Questions to consider for banks include:

- If the bank issues securities to local investors, what is an appropriate rate? This would involve, among other considerations, the structure of the offering (e.g., fixed versus floating rate payments), credit quality (e.g., the capital ratios and loan quality of the issuer), the interest rate environment, and market pricing of comparable instruments.

- What are the capital implications? While current capital rules permit a bank to include trust preferred securities in Tier 1 capital, these rules will eventually be tightened. Currently, the capital rules limit trust preferred securities to 25% of “core capital elements.” Eventually, “core capital elements” will exclude goodwill, thus reducing the amount of qualifying trust preferred securities for institutions with goodwill.

Subordinated Debentures

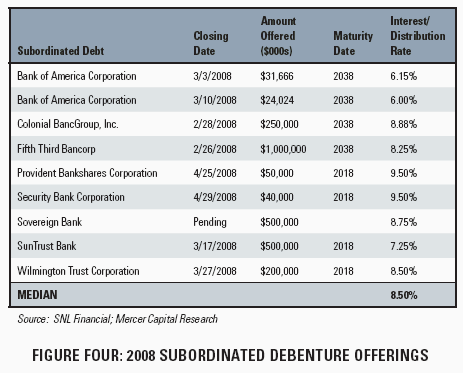

In the event that the bank needs to raise Tier 2 capital, instead of Tier 1 capital, subordinated debentures may be desirable. Subordinated debentures may be included in Tier 2 capital, subject to a limitation equal to 50% of Tier 1 capital. Like trust preferred securities, interest payments on subordinated debentures are tax deductible. Subordinated debentures can be issued at the subsidiary bank level, which may decrease their credit risk for investors, relative to instruments that require the holding company to maintain sufficient liquidity from bank dividends or other sources of funds.

Figure Four indicates the pricing of subordinated debenture offerings in 2008. While few community banks are included in this group of offerings, subordinated debentures may remain an attractive alternative to curing a Tier 2 capital need. Transactions announced in April and May have occurred at interest rates ranging from 8.75% to 9.50%. All of the issuances have involved either ten or thirty year terms.

For community banks where subordinated debentures may solve a problem, the following questions should be considered:

- What is the interest rate? Similar to trust preferred securities, an analysis should consider market interest rates, rates on similar subordinated debentures, and the credit quality of the issuer.

- What is the capital treatment? Subordinated debentures have various capital limits and phase-outs. Over the last five years of the debenture’s maturity, the amount includible in Tier 2 capital declines by 20% per year. In addition, the amount of subordinated debentures includible in Tier 2 capital is limited to 50% of Tier 1 capital. To the extent that the new capital guidelines limit the amount of trust preferred securities includible in Tier 1 capital, banks may find a portion of their trust preferred securities now included in Tier 2 capital. In that case, the trust preferred securities and subordinated debentures would collectively be subject to the 50% limit.

Conclusion

For community banks needing capital, the alternatives possess substantially different impacts on existing shareholders and the bank’s future returns, not to mention divergent capital treatments. For potential investors in community banks, downside protection is important in the present environment. As a result, recent capital raises have included common stock issued at discounts to the issuer’s market price and convertible preferred stock issuances with relatively high dividend rates and low conversion premiums.

Mercer Capital can assist community banks and investors with considering the advantages and disadvantages of the spectrum of capital instruments available to a particular bank, focusing on their effects on existing shareholders and future shareholder returns, as well as evaluating the pro forma capital impact of different instruments and offering amounts. We can also assist banks and investors in determining an appropriate stock price or interest rate in offerings sold to local investors, analyzing, from an investor’s standpoint, the advantages and disadvantages of different proposed investment structures, and providing fairness opinions that the capital offering is fair to a specified group of shareholders.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch 2008-05, published May 28, 2008.

Bankers Expecting 2008 To Be Difficult, If Not Dismal

The majority of respondents to a recent survey presented in the January 2008 edition of Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch are expecting a difficult, if not dismal, 2008. Nearly 83% of respondents believe that the American economy will be in a recession at some point during 2008. In keeping with this theme, virtually all of the respondents believe that interest rates will decline in 2008, and none expect them to increase, with approximately two-thirds of respondents expecting a decline of more than 50 basis points. Given the actions taken by the Fed after this survey, this is not surprising. Despite the current industry focus on credit quality, 40% of respondents listed margin performance and the interest rate environment as their primary concern going into 2008.

Opinions were rather mixed concerning when the industry’s earnings will bottom out, with approximately one-third of respondents indicating the first half of 2008, the majority (43%) indicating the second half of 2008, and the remainder stating that it will be 2009 or beyond before earnings recover. One lone dissenter believes earnings reached bottom in 2007.

However, with the credit crisis still in full force and the dominant topic in the industry for months now, the focus of concern continues to be the quality of the loan portfolio, with 66% of respondents listing that as their primary concern for 2008. Responses were mixed, however, with regard to the types of loans that will present the most problems in 2008.

We’d like to thank everyone who took the time to respond to the survey. We hope that you find the results informative.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, February 26, 2008.

2007: A Year to Forget for Banks

As the world celebrated the closing of another year on December 31, many bankers hoped to soon forget one of the worst periods for bank stock performance in recent history. Credit quality concerns, margin pressure, slowing earnings growth, and a declining housing market took a toll on the market for shares of publicly traded banks, which generally underperformed broader market indices such as the S&P 500 for the year. Seemingly, no public bank was left untouched by the effects of the subprime market collapse and subsequent credit market disruptions; Bank of America and Citigroup, the two largest banking institutions in the U.S., saw price declines of 22.7% and 47.2%, respectively, from year-end 2006 to year-end 2007.

But how has the market affected community banks? Mercer Capital observed two asset size-based bank indices – banks with assets between $1 billion and $5 billion, and banks with assets between $500 million and $1 billion – to gauge the impact of the 2007 financial institution market trends on smaller institutions.

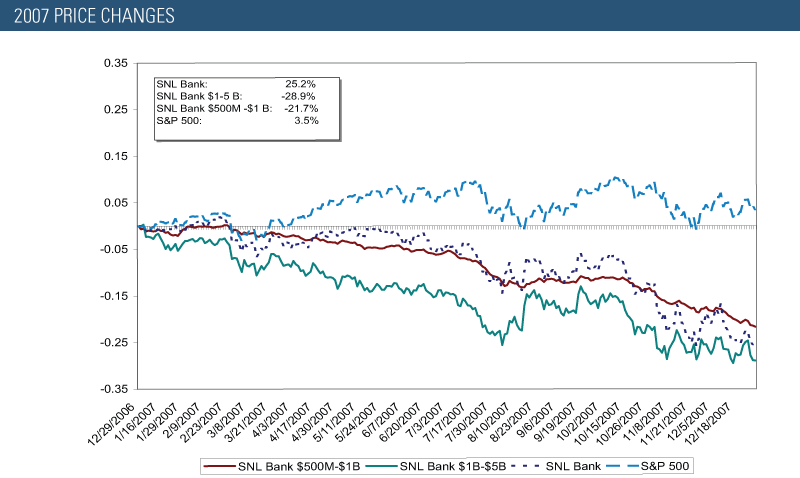

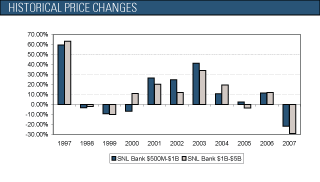

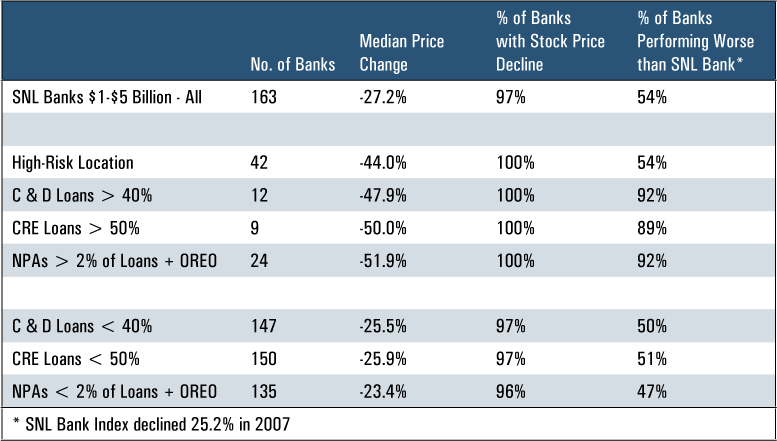

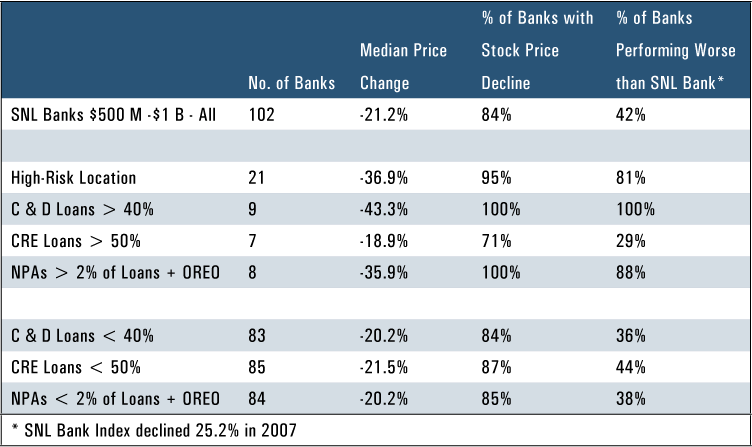

As shown in Figure One, the larger group of banks with assets greater than $1 billion and less than $5 billion felt a more severe impact than the banking industry overall (as measured by the performance of the SNL Bank index) with a year-over-year price decline of 28.9%, reflecting the worst performance observed over the past ten years. For comparison purposes, the SNL Bank index exhibited a decline of 25.2%, while the S&P 500 saw a slight increase of 3.5% for the same period. The unfavorable performance of the larger index was fairly widespread, with 97% (158 out of 163) of the banks reporting price declines in 2007. More than half of the group experienced larger declines than the SNL Bank index overall. Of the five banks with an increase in stock price from 2006 to 2007, four were either targets in a merger or acquisition or the subject of strong takeover speculation.