Fairness Opinions in ESOP Transactions

Q: Why are fairness opinions important?

Prepared by an independent financial advisor, a fairness opinion is just that – an opinion that a proposed transaction is fair (or not) from a financial point of view, to shareholders of a company (either all or a certain specific group of shareholders). A fairness opinion can assist corporate directors and/or ESOP trustees in making or approving decisions concerning strategic and financial events. A fairness opinion can also instill confidence among stakeholders that an action has been thoroughly vetted for its effects on the ESOP and/or the sponsoring company. These opinions can aid in substantiating that decision makers have adhered to the business judgment rule.

Q: Does a transaction involving or affecting an ESOP require a fairness opinion?

The prudent answer is yes. Despite out belief that transactions affecting or potentially affecting an ESOP should include a fairness opinion, such opinions are rare. Some business owners and trustees believe that fairness opinions are time-consuming, costly, uncommon, unnecessary, or excessive for many transactions. Perhaps, in some circumstances, a fairness opinion could be viewed as nonessential. However, every ESOP installation and every ESOP termination, and virtually every significant corporate (or strategic) event in an ESOP sponsoring company would be better served to include a fairness opinion rendered from the financial perspective of the ESOP and its trustee.

That an ESOP transaction or significant corporate event that affects the shareholders or participants of an ESOP company requires a fairness opinion is not specifically codified. Nonetheless, obtaining the service can be a vital, virtually obligatory exercise for any prudent decision-maker, particularly one carrying the burden of a fiduciary obligation to ESOP participants.

Q: If a “valuation” is already part of the process, isn’t a fairness opinion the same thing?

No. A valuation of the transacting interests may be an essential underpinning for a fairness opinion but it is not the only substance of a fairness opinion. Fairness opinions frequently contain additional disclosures, observations, and assessments concerning the circumstances of, alternatives to, and other key factors surrounding a transaction.

In many cases a fairness opinion reaches beyond the instant economics of a transaction to examine the specific terms and context of a transaction. Valuations are often based on the standard of “fair market value” and are constructed using reasonable assumptions and reflections of a hypothetical and rational universe. When an actual transaction arises between specific parties, the situation often includes attributes specific to the parties and the circumstances – in other words, the real world versus the hypothetical world. A well-crafted fairness opinion reaches beyond the hypothetical to examine and document these real world considerations.

Q: What events give rise to the need for a fairness opinion?

The following is a list (non-comprehensive) of the types of events that could give rise to the need for a fairness opinion. A good rule for decision makers concerning the assessment of need for a fairness opinion is if you suspect that any aspect of a transaction is potentially controversial, then an assessment of fairness to the party in question should be considered. The responsibilities and obligations inherent in the ESOP trustee role is serious business.

- The sale and/or issuance of stock to a newly forming ESOP

- The sale of a significant portion or substantially all of the assets or stock of an ESOP company

- The incurrence of significant debt or the financial restructuring (recapitalization) of an ESOP company

- The sale of a significant asset or business segment which is beyond the normal scope of business or corporate activity

- The purchase of a significant asset or business segment which is beyond the normal scope of business or corporate activity

- The liquidation of the ESOP company

- The termination of the ESOP

- The redemption of stock by the company from non-ESOP shareholders

- The changing of corporate entity organization of the ESOP company (“S” election)

- Significant changes to the ESOP plan document

- The commitment of the company to shareholder agreements that place future obligations on the company

- Significant changes in compensation or other financial practices, particularly if such changes are different or contrary to the financial construct upon which a transaction value or ongoing plan valuation is based

Q: Are there specific circumstances that should be considered in the decision to obtain a fairness opinion?

Absolutely. Based on Mercer Capital’s experience, events that are potentially controversial, involve a conflict of interest, or involve decisions and actions other than in the ordinary course and timing of business may require a fairness opinion. As with the previous list of events, the following is not all-inclusive. Additionally, most of the following conditions relate to the sale of an ESOP company or the installation of an ESOP.

- The proposed ESOP transaction includes a stock valuation that is different than the valuation at which actual offers for the stock or the company have occurred

- The proposed ESOP transaction includes a valuation that is different than reflected in recent stock appraisals

- The proposed ESOP transaction includes a valuation that is different than stock valuations called for in shareholder agreements (buy-sell, etc.)

- The proposed ESOP transaction requires high levels of debt financing

- The proposed ESOP transaction includes a valuation that relies on changes to historical compensation and other business practices

- The proposed ESOP transaction and its associated debt may compromise the ability of the company to secure operating and growth capital, such factors which may be a predicate to the proposed transaction valuation

- The cost of financing does not appear to reflect market rates and/or the ESOP transaction is otherwise unable to achieve third-party (independent) financing

- The proposed ESOP transaction entails financing that potentially dilutes shareholders (such as warrants)

- The proposed transaction valuation is not thorough, methodologically complete, and standards-compliant

- The seller of stock to an ESOP is also the ESOP trustee

- The issuance of stock to an ESOP involves the use of sale proceeds for non-recurring payments to non-ESOP shareholders and/or executives of the company

- The company conducts significant business with parties that are owned or controlled by sellers of stock to a proposed ESOP

- A proposed ESOP transaction is occurring at a time of significant change in company performance (declining revenue and/or profitability)

- A proposed ESOP transaction is occurring at a time of significant change regarding senior management, product and service offerings, closure or discontinuation of certain lines of business or locations, etc.

- Alternative transaction bids have been received that are different in price or structure, thereby leading to an interpretation as to whether the exact terms being offered reconcile to the proposed ESOP transaction valuation

- There is concern that the shareholders, trustees and directors fully understand that considerable efforts were expended to assure fairness to all parties

- The board desires additional information about the potential impact of the ESOP transaction and ongoing plan requirements on the company

- An ESOP company is issuing stock options or other equity-based compensation that could adversely dilute the ESOP’s ownership position

- An ESOP company is being sold to a related party or buyer with a current or prior relationship to the company

- An ESOP company is being sold for consideration that is above and beyond that which directly benefits shareholders (including the ESOP) on a pro rata basis (management contracts, non-competes, etc.)

- An ESOP company is being sold to a buyer that intends to employ company executives, trustees, and/or board members subsequent to the closing of the transaction

- An ESOP company is being sold where the company, its board, and/or its executives have not obtained competing bids or assessed alternative strategies for maximizing value and/or achieving liquidity

- An ESOP company has elected not to respond to or to negotiate an offer submitted by a bona fide purchaser of the company

Despite the breadth of the above events circumstances, there are many other situations which likely accompany ESOP transactions and transactions of ESOP owned companies. Your transactions should be thoroughly reviewed from the financial perspective of the ESOP. The transaction process, evolution, negotiations, and other factors that comprise the event (and any circumstances) should be systematically analyzed and documented within the fairness opinion.

Q: What does the deliverable fairness opinion work product look like? What does it contain?

The fairness opinion is a brief document, typically in letter form. However, the supporting work behind the fairness opinion letter can be substantial. This supporting work is often reported and documented in the form of a fairness memorandum that incorporates all material factors, conditions, circumstances, and other considerations which were analyzed, assessed, and disclosed in the development of the opinion. The fairness opinion letter typically makes the affirmative statement that the proposed transaction is fair from the financial perspective of the ESOP.

In the case of a new ESOP or the sale of an ESOP owned company, the fairness exercise virtually always includes a valuation to determine if the ESOP is paying or receiving adequate consideration for the interests it is buying or selling. Generally, the purpose of the valuation is to develop the fair market value of the ownership interest to be transacted. The fairness memorandum also includes all relevant disclosures concerning the transaction, alternatives and potential consequences related to action or inaction regarding the pending transaction, and other assessments that may be specifically requested by the trustee.

In our experience as financial advisors to ESOP trustee, and as an ESOP-owned company, every ESOP situation usually has unique circumstances that require specific assessment. For a confidential discussion about your specific ESOP situation, please contact a Mercer Capital valuation professional.

Mercer Capital’s ESOP Valuation Process

The establishment of an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (“ESOP”) is a complex process that involves a variety of analyses, one of which is an appraisal of the Company’s shares that will be held by the plan. The process of a business valuation is often new and challenging to first-time clients, so we thought it would be helpful to provide elaboration on Mercer Capital’s valuation process to make the experience less intimidating.

Part of the establishment process is a feasibility analysis to determine whether the company is a good and appropriate candidate for an ESOP. Typically the company engages a number of advisors who coordinate to assist the company and its shareholders in making this determination. A firm that specializes in ESOP implementation is generally hired, as well legal counsel (if the ESOP service firm does not have internal legal resources), an accounting firm, a banker (if there are plans to leverage the ESOP), and an independent Trustee.

An appraisal firm is hired and works with the company and its team of professional advisors to determine the characteristics of the stock held by the Plan and to place a value on the shares. If the company is undecided about whether a plan will actually be implemented and is in the discovery phase of the process, the valuation firm may initially be retained to provide a limited appraisal or valuation calculations and at a later time prepare an appraisal in accordance with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, the Department of Labor and the Internal Revenue Service guidelines as well as Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (“USPAP”).

However, whether the initial estimate of value is a limited appraisal, valuation calculations or a stand-alone appraisal, if the ESOP is eventually implemented there are certain procedures and requirements necessary to develop and prepare a fully documented appraisal that is in compliance with USPAP. The following discussion will provide an overview of the steps necessary to prepare an appraisal.

Introductory Phase

During the initial introduction, professionals of Mercer Capital will request certain descriptive and financial information (usually recent audits and marketing brochures) to help define the scope of the business in the context of an ESOP appraisal. Defining the project is a critical phase of the valuation, and can be accomplished with telephone and personal visits with the company and its professional advisors, as required.

Engagement Phase

Once the valuation project has been defined, an Engagement Letter is issued setting forth the key elements of the appraisal assignment. Typical elements included in the letter are the name of the client (usually the Trustee of the Plan), the official name of the entity to be appraised, its state of incorporation or organization, its principal business location and the specific business interests to be appraised. Additionally, the letter will indicate the appropriate standard of value (fair market value), the premise of value (controlling or nonmarketable minority interest), the effective date of the appraisal, and the type of report to be produced. There are three scopes of work, including appraisals, limited appraisals and calculations as defined by the Business Valuation Standards of the American Society of Appraisers.

The Engagement Letter will provide a descriptive project overview, outline the qualifications of the appraiser and set forth the timetable and fee agreement. Accompanying the Engagement Letter is a comprehensive checklist request for information which is forwarded to the company. The information requested includes the company’s historical financial statements and detailed operating and structural information about the business, and the market in which it operates.

The Valuation Phase

Upon execution of the Engagement Letter by the responsible party, including a response to the checklist request for information, Mercer Capital will begin its preliminary analysis of the company, including research and review of appropriate industry data and information sources. As securities analysts, we recognize that an appraisal of common stock represents an assessment of the future at a current point in time. Yet, most of the information available to the analyst is historical information. The future will likely change relative to the past, and we know that management will be largely responsible for making that future happen.

Accordingly, upon review of the checklist and industry information, we will schedule an on-site appointment with management to discuss the operations of the business. Normally, one or two business valuation professionals will visit with management at the headquarters location to:

- Review in detail the Company’s background, financial position, and outlook with appropriate management personnel

- Review appropriate corporate documents not normally exchanged by mail

- Tour the operations

- Respond to questions from management

The Company visit provides an important perspective to the business valuation, since it puts the analyst in direct contact with the individuals responsible for shaping the future performance of the Company. In a very real sense, management’s input will shape the investment decisions to be made by the appraiser in reaching a conclusion of value.

Following the Company visit, the analysis is completed, making specific documented adjustments discussed with management, in context with more subjective conclusions involving the weighting of some factors more than others. Prior to sending a draft report, the valuation analysis and report will be thoroughly reviewed by other in-house analysts to ensure that the initial conclusions are well- reasoned and supportable.

The client’s review of our draft report is an important element in the process. We believe it is important to discuss the appraisal in draft form with management and the Trustee of the ESOP (if one has been appointed at the time of our analysis) to assure factual correctness and to clarify any possible misunderstanding from our company interview.

Upon final review, the valuation report is signed by the major contributing appraiser, and is reproduced in sufficient number for the Plan’s distribution or documentation requirements.

In Summary

If you are considering an ESOP, or have one already in place, and would like to discuss any valuation issue in confidence, please give us a call. We know that most companies do not run their businesses to be able to immediately respond to an appraiser’s inquiries, but our depth of experience will lead you easily through the valuation process.

Changing ESOP Appraisers: Why It Might Be Necessary and How to Accomplish It

ESOP valuation is an increasing concern for Trustees and sponsor companies as many ESOPs have matured financially (ESOP debt retired and shares allocated), demographically (aging participants), and strategically (achieved 100% ownership of the stock).

Given these and other evolving complexities (including the proposed DOL regulation which would designate ESOP appraisers as fiduciaries of the plans they value), it is sometimes necessary or advisable for ESOP Trustees and the Boards of ESOP companies to change their business valuation advisor.

This article addresses why a Trustee or sponsoring company might or should opt for a new appraisal provider, as well as what criteria, questions, and qualities drive the process of selecting a new appraiser.

Why a Change in Appraisers Might Become Necessary?

There are potentially many circumstances and/or motivations that can compel an ESOP Trustee to seek a new valuation advisor.

- The current appraiser is no longer available or is unwilling to perform the annual plan year valuation. Due to retirement, firm closure, conflict of interest, or some other reason that is beyond the control of the Trustee or sponsor-company board, the legacy appraiser is not available or willing to perform annual plan year valuations.

- The legacy appraiser has resigned from the ESOP appraisal due to evolving regulatory decisions from the DOL. As of the drafting of this article, the DOL has requested and considered feedback and testimony concerning the designation of ESOP appraisers as fiduciaries of those plans they value. Collectively, the ESOP appraisal community has responded in opposition. A number of ESOP valuation firms have identified this issue as a potential “make or break” concerning the continuation of ESOP appraisal services. As such, if the proposed regulations are enacted, growing numbers of sponsoring companies may be forced to identify and retain a new appraiser because their legacy appraiser has resigned from the ESOP appraisal. This issue and its ramifications for Trustees, sponsoring companies, and ESOP appraisers warrant continued monitoring.

- Growth and/or evolution in the sponsor company’s business model, industry, market complexity, management, or otherwise can take a business from a once comfortable and familiar place for the appraiser to one that is beyond their resources and competencies.

- The maturation of the ESOP may be creating new or increased concerns regarding the valuation or other Trustee considerations that are not being adequately addressed or integrated into the valuation or into other financial advisory feedback and support often provided by valuation experts.

- The legacy appraisal product does not reflect current valuation theory, methodology, and/or reporting standards. Trustees that suspect their valuations are lacking in thoroughness, accuracy, or reasonableness might be well-served to obtain an independent review of the work to identify problem or missing content before any decision is made to change appraisers.

- The sponsor company has experienced volatile or declining performance that is not quantified or otherwise addressed in the ESOP valuation. There has been much written by valuation practitioners concerning the relative volatility of closely held valuations to the valuations of the broader (public) market place. The lack of reconciling valuation information and conclusions to market and/or financial evidence may suggest a variety of ills ranging from complacency to advocacy.

- The appraisal conclusions and underlying valuation components have not been reconciled with prior valuations or over time. Trustees need to be able to examine the underlying performance, market evidence, and valuation treatments over time in order to offer constructive feedback and questions, as well as to track the investment and operating performance of the sponsor company.However, keep in mind that valuation practitioners must be allowed to enhance or augment their reports and methodology with the passage of time, the advancement of analytical treatments and approaches, the evolution of the body of knowledge, in response to draft review processes, and to comply with changes in regulations and compliance requirements.

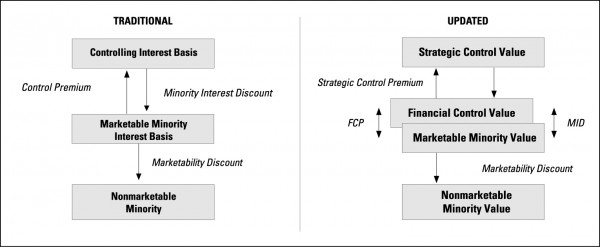

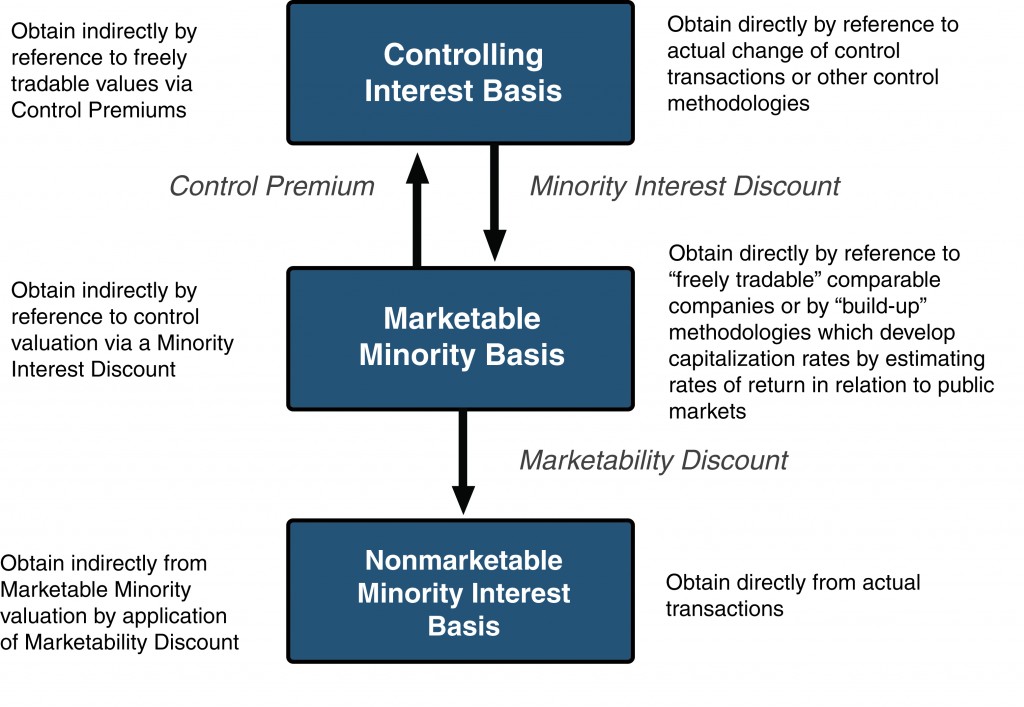

- Excess control premiums have been applied to a controlling interest ESOP valuation resulting in a potentially higher than reasonable value and causing serious ramifications for participants and sponsor companies.Over-valuation is a consistent issue in many ESOP appraisals. A principal cause of over-valuation is the direct or implicit application of unwarranted or unsupportable control premiums.Control premiums, particularly when styled as specific and finite adjustments in a valuation, are generally not advisable in the appraisal world unless they are explained and reconciled financially. If the appraiser cannot articulate the financial basis for the application of (and the magnitude of) a control premium by direct reference to earnings enhancements, risk mitigation, enhanced growth rates, or other fundamental valuation drivers and assumptions, then a Trustee would be well-served to question the appropriateness of the premium.Excess control premiums may exist below the surface in a valuation in the form of unsupportable adjustments to earnings and cash, aggressive capital structure assumptions, excessive growth rates, improper or unsupported weighting of valuation methods, unsupportable averaging of past performance that is unlikely to return in the foreseeable future, low rates of return, inflated financial projections, or numerous other treatments.

Some appraisals may subtly (or unintentionally) rely on the upper end of the range of valuation assumptions, thereby compounding a series of seemingly reasonable control treatments or adjustments into an unsupportable valuation conclusion.

Over-valuation can also result from a failure to reasonably modify or abandon control-style treatments over time due to changes in market evidence, economic/financial cycles, or changes in company performance and/or outlook. Has the company’s management and/or non-ESOP shareholders lived up to their end of the bargain by modifying their compensation to comply with valuation treatments applied to develop transaction pricing? If not, how has the appraisal treated the issue?

- Valuation discounts are insufficient or missing, resulting in valuation conclusions that do not comply with the level of value defined by the Trustee. Many minority interest ESOPs are effectively valued on a quasi-control basis. Is this reasonable or proper? Is the marketability discount appropriate in light of the sponsor company’s financial health and the needs of plan participants?

- The aging of baby boom participant pools requires that the demographics of plan participants be examined for diversification or retirement needs.Repurchase obligation is a seminal issue in ESOP valuation. Appraisers should inquire about projected retirement needs of both ESOP participants and other shareholders or significant managers. Repurchase obligation studies are the order of the day for Trustees and sponsor company boards. In some cases, non ESOP shareholders requiring accommodation via stock redemption may have needs or expectations that conflict with needs arising from an accumulation of ESOP participants awaiting contributions and/or distributions for retirement or diversification purposes.

- A change in the ESOP Trustee may bring about a change in the appraiser.

- The ESOP valuation fails to reconcile to non-ESOP appraisals or other appraisals used for capital raising or other purposes. There are reasons why this could or should be the case. However, significant valuation events that fail to reconcile to the ESOP valuation can suggest serious issues.

- A lower professional fee is needed or, perhaps, the conclusion of value is not desirable. Fee sensitivity is arguably a good trait for ESOP Trustees, as long as valuation quality is not compromised. However, shopping the valuation for a targeted treatment or result is a dangerous endeavor.

- There are service and timeliness issues with the current appraiser. The need for expediency cannot compromise accuracy or completeness in the valuation. The timing and responsiveness of information production is the key to a good appraisal experience.

- The ESOP is terminating. Termination events often involve fairness opinions and other advanced considerations, prompting a change in the appraiser or the use of a secondary appraiser to advise the Trustee in a consultancy role. The same may be true for secondary and/or consolidating ESOP transactions.

The Process of Selecting the New ESOP Appraiser

When the decision has been made to select a new qualified appraiser, it is appropriate for the Trustee to begin an orderly process of interviewing more than one potential valuation expert in order to make an informed decision.

Therefore, Trustees and/or sponsoring companies should consider the following:

- Industry Expertise or Valuation Expertise? Although “industry experts” in a variety of industries are abundant, it is generally advisable to prioritize valuation expertise over industry expertise in the ESOP world. Industry experts, although knowledgeable about their particular industry, frequently lack even a basic understanding of the concept of fair market value as it pertains to a particular level of value in the context of a private company ESOP. It is advisable to look for appraisers with a working and current knowledge of ESOP valuation issues.

- Is the appraiser a sole practitioner or the member of a firm with other skilled ESOP appraisers that can readily stand-in if the original practitioner leaves the firm, retires, or exits the field? The involvement of multiple professionals (often contributing to or administering to varying elements of the valuation process) working collectively under the supervision or a senior-level practitioner may provide the back-up that mitigates the potential disruption caused by the departure or unavailability of the legacy/primary appraiser.

- The ESOP appraisal experience of the business valuation firm, including the number of ESOP valuations performed over the history of the firm, as well as the current number of ESOP appraisals performed.

- Non-ESOP appraisal experience of the business valuation firm. Some ESOP stakeholders might consider a firm that only specializes in ESOP appraisals an advantage. Others could perceive such a service concentration as inherently risky or too professionally confining for the appraiser to gain collateral professional financial services experience.

- The professional credentials held by the business appraisers within the firm being considered. Professional valuation credentials generally include the following: Accredited Senior Appraiser (ASA), Accredited in Business Valuation (ABV), Certified Business Appraiser (CBA), Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA), and Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA). To date, government agencies do not certify appraisers in the discipline of business valuation. Accordingly, professional credentials and valuation experience are critical considerations in vetting a new appraisal firm.

- Affiliation with the ESOP Association and/or the National Center for Employee Ownership; articles published; speeches given; conferences attended.

- The valuation methods typically employed and the relative weight applied to each.

- Has a regulatory challenge ever been leveled against the proposed ESOP appraiser?

- The appraiser’s position regarding:

- an ownership control price premium applied to an ESOP’s purchase of the employer corporation stock and, conversely, a minority interest discount applied to an ESOP’s purchase of employer corporation stock.

- a marketability discount in view of the ESOP participants’ put option rights.

- the typical range of the marketability discount applicable to ESOP-owned employer stock.

- The appraiser’s treatment and/or consideration of the ESOP’s repurchase obligation.

- The appraiser’s experience as an expert witness in litigation or plan audit matters involving the IRS, the DOL, or ESOP participants and the outcomes of such events. It could well be that an experienced ESOP appraiser with limited or no litigation experience is preferable to one that has repeatedly been required to defend their appraisals in audit and litigation proceedings.

- Estimates of professional fees (both current and on-going).

- The appraisal firm’s valuation process, including an understanding of the timing to complete the valuation engagement.

- The extent to which the financial advisor expects to work interactively with sponsoring company management during the valuation process.

The Trustee has a role to play in providing pertinent information to the prospective appraisal firms such that they can understand the proposed project and provide a comprehensive proposal of services. As such, the Trustee should provide the following information to the appraiser candidates:

- Historical financial statements (typically 5 years)

- Previous ESOP valuation reports

- History of the subject plan

- Information on the ESOP sponsor company

The Trustee’s selection decision should be based on the overall qualifications of the business appraisal firm. Discussion of the probable valuation outcome during the selection phase could be misleading or taint the process. In cases where a new appraiser serves as a review resource to the Trustee, there could be situations when differences of treatments and methodologies are discussed, as well as the impact that valuation modifications or additions would have on an appraisal issued by the previous appraiser. In such cases, the new appraiser has the burden of independence and credibility and Trustees have the obligation of obtaining the best information and not a predetermined outcome from a change in the appraisal firm. As stated previously, shopping the valuation for a targeted treatment or result is a dangerous endeavor.

The selection process should also be reasonably documented so that the questions of “why was a change necessary?” and “how was the selection process undertaken?” can be answered by the Trustee.

Conclusion

There are risks involved when making the decision to select a new appraiser, including a change in valuation methodology, a possible meaningful change in share value, and the perceived independence of the Trustee (and appraiser) from the perspective of regulators and/or plan participants. Some Trustees are simply averse to the potential backlash or complications that can arise from changing appraisers. However, in many situations, a change is needed and prudent and a lack of change can be viewed as creating or worsening a valuation issue.

The selection process should serve to ensure that the change in appraisers minimizes or mitigates the negative impact on the ESOP, and the ESOP participants (or that a change is accompanied by necessary, long-term considerations, even if a change in the valuation provider results in a meaningful near-term impact on the ESOP) and should be rigorous enough to withstand scrutiny from government regulators and plan participants.

Given the economic uncertainties in recent years, the continuing globalization of markets, the evolution of valuation science, and the growing concern for DOL compliance, Trustees must retain the right and conviction to source valuations from providers that can properly develop and defend their appraisal results.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Value Matters(TM) 2011-01, released March 2011

The 1042 Rollover

Resurrected Interest in Tax Benefits for Selling Shareholders in ESOP Transactions

For many business owners, the investment in their company is their most significant asset. Shareholders of closely held businesses, particularly those on the crest of the baby boom wave, are rigorously searching for exit plans to diversify their portfolios and to plan for the next stage of life. It certainly helps if the exit plan is aligned with a compelling estate and tax strategy. In this era of challenging credit conditions and economic uncertainty, interest in Employee Stock Ownership Plans (“ESOPs”) is rising as sellers come to understand the varying opportunities related to transaction financing and to potential tax benefits accorded qualified sellers to ESOPs. One such potential benefit for selling shareholders is the 1042 rollover.

Internal Revenue Code Section 1042 provides beneficial tax treatment on shareholder gains when selling stock to an ESOP. Given certain conditions, capital gains tax can be deferred allowing the full transaction proceeds to be invested in Qualified Replacement Property (“QRP”). Long-term capital gains are recognized upon the liquidation of QRP securities at a future date after a required minimal holding period. If the QRP is not liquidated and becomes an asset of the seller’s estate, it enjoys a stepped up basis and avoids capital gains completely.

Summary Requirements

In order for the sale of stock to qualify for a 1042 rollover, several requirements must be met:

- The seller must have held the stock for at least three years;

- The ESOP must own at least 30% of the total stock immediately following the sale; and,

- The seller must reinvest the proceeds into “qualified replacement properties” within a 12 month period after the ESOP transaction.

Qualified replacement property is defined as stocks and bonds of United States operating companies. Government securities do not qualify as replacement properties for ESOPs. The seller must invest in these properties within a 15 month period beginning three months prior to the sale and ending 12 months after the sale. The money that is invested can come from sources other than the sale, as long as that amount does not exceed the proceeds. However, not all of the proceeds have to be reinvested. If the seller chooses to invest less than the sale price, then he or she will have to pay taxes on the amount not invested in QRP. In order to meet the 30% requirement, two or more sellers may combine their sales, provided that the sales are part of a single transaction. The sponsor Company must be a C Corporation for selling the shareholder to qualify for a 1042 rollover.

The shares sold to the ESOP can not be allocated to the ESOP accounts of the seller, the relatives of the seller (except for linear decedents receiving 5% of the stock and who are not treated as more-than-25% shareholder by attribution), or any more-than-25% shareholders.

1042 Rollover Benefits

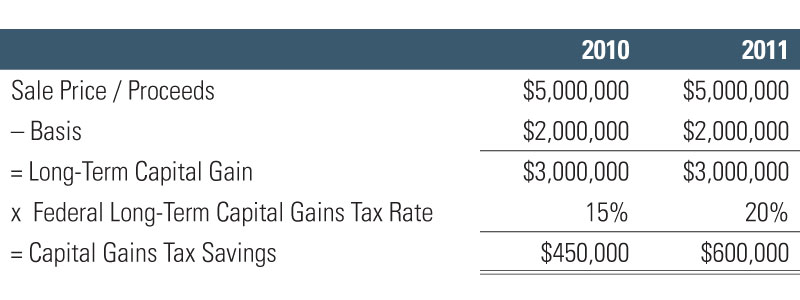

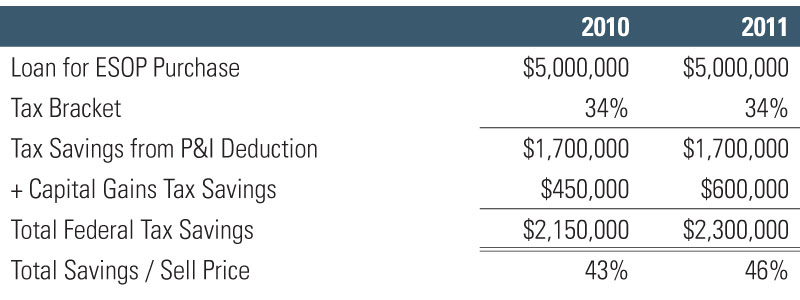

The current federal capital gains tax is 15%, but if no legislative action is taken, on January 1, 2011, the federal (long-term) capital gains tax will revert to 20%, making the 1042 rollover option more attractive and beneficial to business owners. If an owner with a $2,000,000 basis sells his or her shares for $5,000,000 and realizes a capital gain of $3,000,000, he or she would defer or save $450,000 in capital gains taxes under today’s tax structure. Given no legislative action and a 2011 reversion to previous capital gains rates of 20%, a seller would defer or save $600,000 in federal capital gains tax on the sale as shown below.

If legislative action is taken that results in an even higher capital gains tax rate, a 1042 rollover becomes even more attractive.

Leveraging the sale of stock to the ESOP can provide further financial benefit to the company and its shareholders. Sellers often use all or part of their replacement property as collateral for loans used to finance ESOP purchases. Financing costs are significantly lower for corporations that borrow to purchase owner’s stock for ESOPs than for conventional stock redemption because the corporations are able to deduct the principal and interest payments on the loan when used to purchase ESOP stock. If a corporation is in the 34% tax bracket and borrows $5,000,000 to purchase the ESOP stock, it would save $1,700,000 in federal income taxes. Combined with the $450,000 in savings with the current capital gains tax rate, the federal tax savings would be $2,150,000 or 43% of the selling price. If capital gains tax rates revert to the previous rate of 20%, the total federal tax savings would be $2,300,000 or 46% of the selling price.

S Corporations

Although S Corporations are allowed to have ESOPs, the 1042 rollover option is not available to the shareholders. In most cases, there is a 25% limit on tax-deductible contributions made by employers to ESOPs. C Corporations do not have to count interest payments on ESOP loans as part of the 25% limit, but S Corporations do. There is no required length of time during which a corporation must have C status to receive the benefits of the 1042 rollover, which means that an S Corporation can change its status and receive the differed tax benefits without delay. However, this change in status can have negative tax effects that would cancel out any benefits gained from the 1042 rollover status due to different accounting methods, so a change in status may not always be the best option.

ESOP Financing

Given the corporate development criterion of most strategic and financial buyers in the markets today, relatively few small-to-medium sized business owners can achieve an exit via a transaction with an external buyer. Throw in the difficulties of financing acquisitions and many shareholders of successful and sustainable businesses may be locked out of certain exit strategies. Increasingly, sellers to ESOPs are financing their own transactions. Before the financial crisis struck, many ESOPs sellers found that continuing business involvement and loan guarantees were required by ESOP lenders. The realization: seller financing in today’s market represents little incremental risk and time than in previous more favorable markets. True, many valuations may be lower than a few years back, but most good ESOP candidates have likely fared better than the markets as a whole. Absent the need for lump sum liquidity, and given a strong and early start to longer-term exit planning, seller-financed ESOPs may be a viable and preferable path for many closely held business owners.

What Goes Down Must Go Up

Confused? We’re alluding to taxes – in the context of a nation whose thirst for government spending had been both red and blue in the past ten years and shows little sign of being quenched. The likely result, relentless tax pressures even if significant belt tightening occurs. For those business owners committed to the long-term success of their businesses, concerned about the fate of their employees, and who have a desire for favorable tax treatment in the course of achieving succession and exit planning, the ESOP is a viable alternative. As taxes went down in previous years, so it seems they are going up. As ESOP formation waned in a previous market where external exit opportunities abound and have now collapsed, ESOP formation appears primed to go up. ESOPs represent one of the few exit plans that can be timed and entered into without a change of control. In an increasingly uncertain world, throw in a healthy dose of tax advantages for qualified sellers and it is hard not to view the ESOP with increased interest.

Mercer Capital has over 35 years of experience providing ESOP valuation services and is employee-owned, giving us a unique perspective. For more information or to discuss a valuation issue in confidence, give us a call at 901.685.2120.

Article originally appeared in the September/October 2010 issue of Value Matters(TM).

How ESOPs Work

ESOPs are a recognized exit planning tool for business owners, as well as a vehicle for employees to own stock in their employer company. However, most business owners and their advisors are unfamiliar with how an ESOP works. The mechanics of an ESOP can vary somewhat, but there is a basic common functionality to all ESOPs. Below, we discuss the mechanics of leveraged and non-leveraged ESOPs.

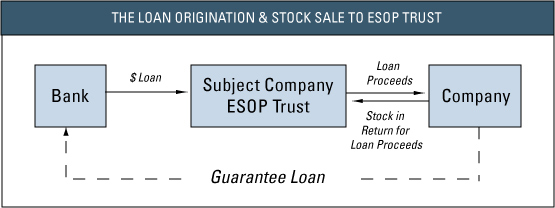

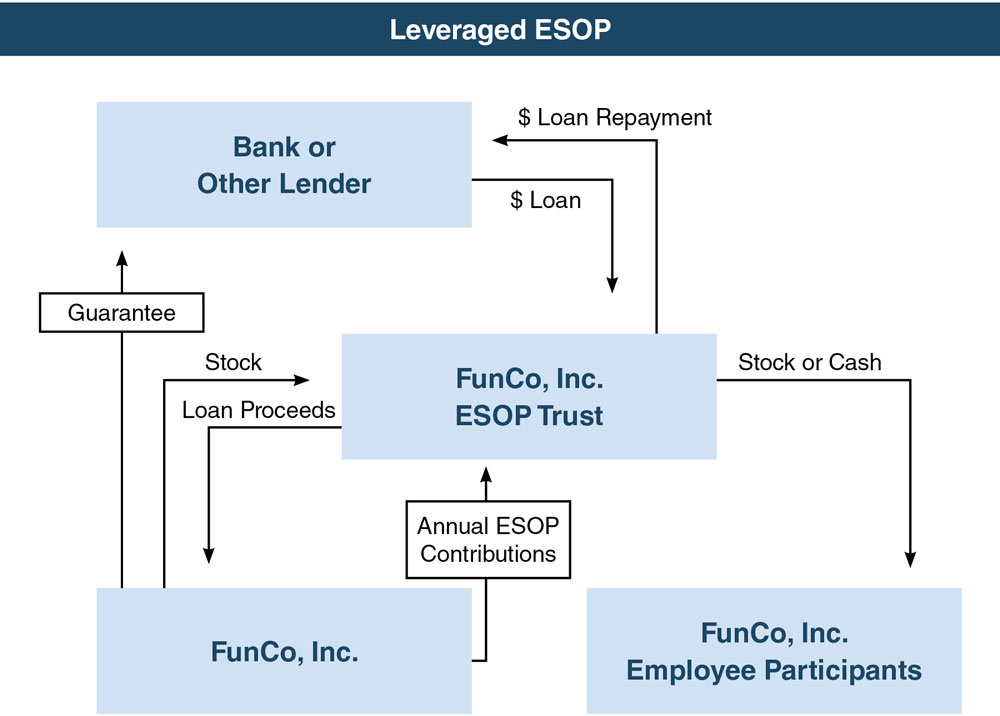

Most ESOPs are leveraged and involve bank financed purchases of either newly issued shares, or more often, the stock of a selling shareholder. The Company funds its ESOP via annual contributions as a qualified retirement plan and the plan effectively uses those funds to repay the debt used for the purchase.

Leveraged ESOPs tend to be more complicated than non-leveraged ESOPs. A leveraged ESOP can be used to inject capital into the Company through the acquisition of newly issued shares of stock. Figure 1 illustrates how the initial leveraged ESOP transaction typically works.

Subsequent to the initial transaction, the Company makes annual tax deductible contributions to the ESOP, which in turn repays the loan. Stock is allocated to the participants’ accounts — just as it is in a non-leveraged ESOP — enabling employees to collect stock or cash when they retire or leave the Company. ESOP participants have accounts within the ESOP to which stock is allocated. Typically, the participant’s stock is acquired by contributions from the Company — the employees do not buy the stock with payroll deductions or make any personal contribution to acquire the stock. An exception to this norm could involve roll-overs of participant’s funds from alternative qualified plans sponsored by the Company. Plan participants generally accumulate account balances and begin a vesting process as defined in the plan. Contributions, either in cash or stock, accumulate in the ESOP until an employee quits, dies, is terminated, or retires. Distributions may be made in a lump sum or installments and may be immediate or deferred. The typical annual flow of funds for a leveraged ESOP is illustrated in Figure 2.

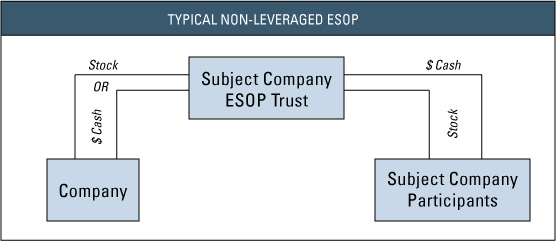

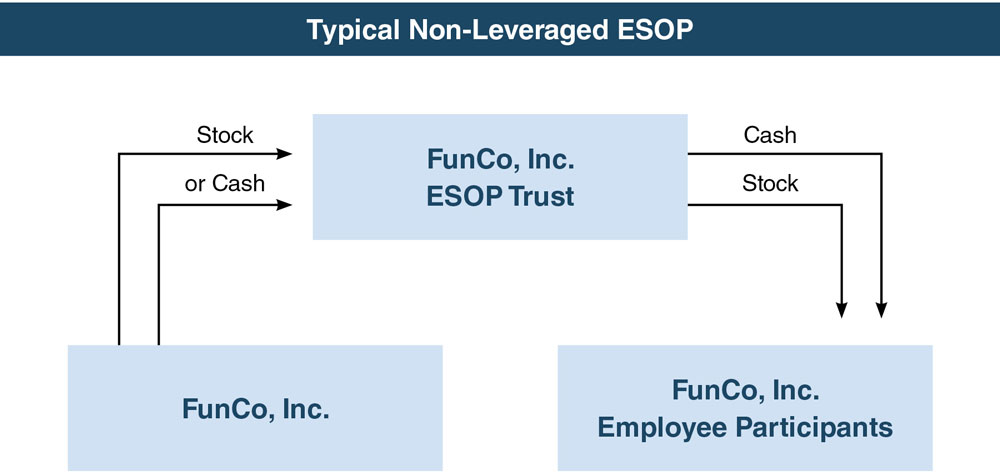

Although non-leveraged ESOPs have certain tax advantages to selling shareholders, they generally tend to be an employee benefit, a vehicle to create new equity, or a way for management to acquire existing shares. The Company establishes an ESOP and either makes annual contributions of cash, which are used to acquire shares of the Company’s stock, or makes annual contributions in stock. These contributions are tax deductible for the Company. As in a leveraged ESOP, the employee/participant vests according to a schedule defined in the plan document, and stock accumulates in the account until the employee/participant leaves the Company or retires. At that time the participant has the right to receive stock equivalent in value of his or her vested interest. Typically, ESOP documents contain a provision called a “put” option, which requires the plan or the Company to purchase the stock from the employee after distribution if there is no public market for it, thus enhancing the liquidity of the shares. Figure 3 illustrates a non-leveraged ESOP.

As ESOP participants roll out of the plan at termination or retirement, the ESOP or the Company purchases the employee’s plan shares based on the terms specified in the plan document. Plan design and administration are crucial to a successful ESOP experience and require the participation of specialized financial and legal advisors.

As with all qualified retirement plans, there are rules and requirements pertaining to annual contribution limits, vesting, share allocation, plan administration, and other functional aspects which are beyond the scope of this overview.

Sellers of stock to an ESOP may enjoy certain tax benefits related to their sale proceeds, and the Company (the sponsor) may enjoy tax benefits related to its contributions to the ESOP. Thus, ESOPs are often postured by business advisors as a tax advantaged exit strategy. Please refer to other articles on Mercer Capital’s website or contact me or Tim Lee for more information.

Mercer Capital is itself an employee-owned firm. We value scores of ESOPs annually and provide fairness opinions and other valuation services on a regular basis to many other plans. To discuss a valuation issues in confidence, give me a call at 901.322.9716.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Matters (TM) 2009-03, published March 31, 2009.

ESOP Appraisal for a Cyclical Business

The Employee Stock Ownership (ESOP) appraisal utilizes the same tools and techniques of any fair market value appraisal assignment, but with an added emphasis on analyst expertise in understanding the market, the economy, and the underlying business model for the subject company. The ESOP appraisal has the added sensitivity of the Plan participants and trustees who don’t like to see the value of allocated shares reflect a decline on the annual plan account statements, especially if it’s at redemption time.

We all recognize that in the real world, stocks frequently do decline in value, and closely held ESOP shares should be no exception. However, the appraiser of ESOP shares is in a unique position to interpret market, industry, and company performance in the context of a fair market value appraisal. This analysis is even more important for a cyclical company, where sales and earnings declines are expected but seldom forecast. As appraisers, we frequently utilize the tool of average or weighted average earnings in context with a specific company risk premium and earnings growth rate to develop a capitalization rate, or multiple of ongoing earnings. For an annual ESOP appraisal update, the use of average or weighted average earnings can work against the reality of the situation, and it is here that the analyst must have a firm grasp on the underlying trajectory of earnings as the subject company

navigates through the down cycle, in anticipation of the expected, but unknown, upside.

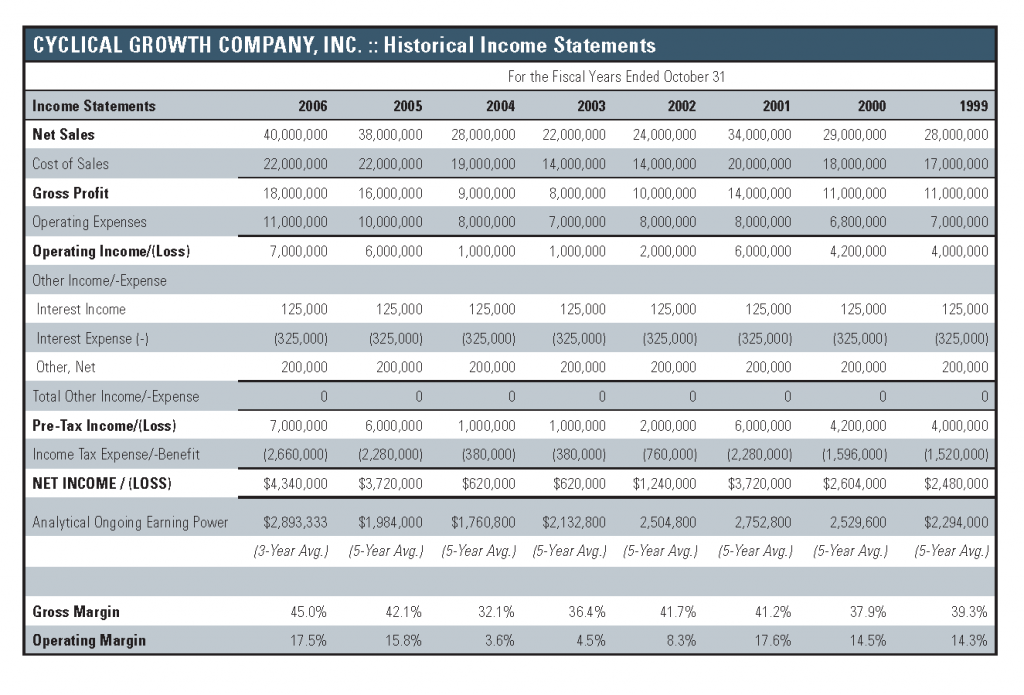

Consider the case of Cyclical Growth Company, Inc., (“CGC or the “Company”), a large manufacturer of industrial products, subject to normal business cycle fluctuations. The eight year summary of operations shown in Figure One reflects the peak of the last cycle and the recovery to date in 2006.

During the period 1999 – 2001, earnings are advancing but not at an accelerating rate, and appear in line with management’s expectation of a long term growth rate approximating 5%. With the benefit of hindsight, we know that 2001 was the peak of the cycle, we just don’t know that for the 2001 appraisal.

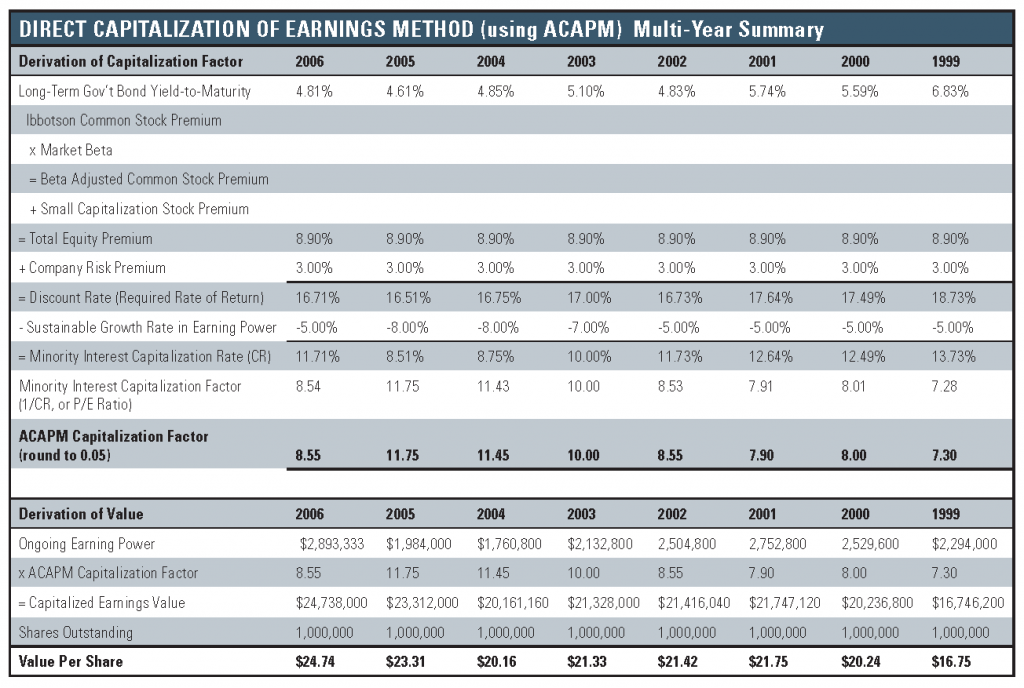

Accordingly, a reasonable derivation of the capitalization factor by means of the Adjusted Capital Asset Pricing Model during this time period may include using a 3% specific company risk premium and a 5% sustainable growth rate in earning power. As shown in Figure Two, this results in a multiple of earnings at 7.90x for 2001, applicable to ongoing earnings power.

When applied to the ongoing earning power of CGC, based on 5-year average earnings, a value of $21.75 per share is indicated. Again, this was the peak of the cycle, we just don’t know that yet.

By 2002, it is evident that this is the first year of the downturn. As shown in Figure One, earnings approximate one-third of prior levels and sales are down substantially. The Company is able to maintain about the same gross margin as in the prior year, but the cut in SG&A expenses is not enough to avoid an operating margin at about half of the peak (2001) year, although profitability is maintained. Specific company risk has not changed, although interest rates are now lower in the recession. Since the length and depth of the downturn are unknown, and the average earnings analysis has produced ongoing earnings of $2.5 million (versus reported earnings of $1.2 million), it may still be reasonable to expect a long term growth rate of earnings at 5%, resulting in only a modest decline in value compared to 2001.

By 2003, it is clear that the recession and decline in sales and earnings are for real. Reported earnings are now about half of 2002 and approximate about 16% of the peak (2001) year, although still profitable. The length and depth of the recession are still unknown, but recent history tells us that recessions are shorter than expansionary phases. The 5-year average earnings analysis still provides some moderation to ongoing earnings (now assuming a reasonable recovery). With the specific company risk premium unchanged, and given the underlying growth rate of earnings approximating 5%, it may now be feasible to assume that with earnings acceleration upon the recovery, the long term growth rate of earnings for the determination of a single-point capitalization rate may be 7%. This results in a higher multiple on lower earnings, which is exactly what the market would typically do if the Company were publicly traded.

By 2004, the sales decline has now ended, but profitability has not fully recovered, as the Company has maintained sales with lower margin products, and boosted SG&A expenses back to the 2002 – 2001 level. The operating margin at 3.6% is the lowest in the last six years, and earnings at $620,000 matches 2003’s performance, Management may have a feel for a prospective, but undefined recovery at this point, but we will not know that this is the nadir of the cycle until we can look back on it. Given the relatively low ongoing earnings based on the 5-year average earnings analysis, in context with a prospective, but undefined recovery, it may be reasonable to boost the growth rate of earnings to 8% for 2004, anticipating a recovery by 2005.

By 2006, the recovery is clearly in place, with sales and earnings greater than expected. The gross margin has improved to its highest level, exceeding the peak in 2002 – 2001. Operating expenses have increased too, with additional catch-up bonuses to employees who sought to maintain market share in the recession. The operating margin now approximates the peak in 2001. Earnings are at the highest level ever, at $4.3 million. With the Company clearly beyond the recession, it may be time to modify the average earnings analysis to a 3-year average, which picks up the two recovery years, but tempers that with the last diminutive year of the recession. From this recovery earnings level, the earnings growth rate as a component of the capitalization rate is no longer 8%, but can reasonably be expected to achieve the 5% projected by management.

During the economic cycle described, the Company has experienced significant changes in financial performance. While consistency is important in an ESOP appraisal, the analyst need not be crucified on the cross of consistency. Given the modest changes in interest rates, and a constant specific company risk premium, the key variables here involve the growth rate of earnings and the average earnings base (ongoing earnings) to which the capitalization multiple is applied. It is at this decisive analytical juncture that the seasoned analyst has an edge: experience counts. Experience with the variance of market cycles and the nature of equipment manufacturers during different phases of the economic cycle, in context with the legacy experience in the analysis of the Company and its management all comes together to provide an analytical perspective allowing the adjustment (and defense!) of key benchmarks in the multiple and the ongoing earnings to which it is applied. A summary of the capitalization of earnings approach since the peak in 2001 is shown in Figure Two.

In the case of Cyclical Growth Company, Inc., the analysis has reflected the reality of the marketplace at key junctures in the economic cycle. While the future is uncertain during the freefall part of the cycle, the averaging of earnings provides some moderation to the decline (assuming, of course, that earnings actually will recover). Moderating the growth rate at the proper time, based on experience, assigns a higher multiple to lower earnings, which is exactly what the public market does. Finally, with the recovery in place, a re-adjustment of the growth rate of earnings and the averaging process results in a reasonable assessment of the future at the valuation date. From the ESOP participant’s point of view, the per share value declined only modestly over three years, but not nearly as severely as the decline in earnings for those years, and the value upon recovery exceeds the prior peak in 2001.

If you need the experience of a seasoned analytical team to define and defend the appraisal of your ESOP, or for other business valuation resources, please give us a call at Mercer Capital to discuss your specific requirements in confidence.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Transaction Advisor, Vol. 10, No. 2, September 2007.

ESOP’s Fables: Increased Scrutiny for ESOP Fiduciaries

Webster’s dictionary defines a "fable" in several ways: 1. a feigned story or tale, intended to instruct or amuse; 2. a fictitious narration intended to enforce some useful truth or precept; 3. the plot, story or connected series of events forming the subject of an epic or dramatic poem; 4. any story told to excite wonder; 5. fiction, untruth, falsehood. The title of this article is a play on the venerable Aesop, whose musings turn out to be highly relevant to world of ESOP oversight and valuation. Mercer Capital renders services for ESOP fiduciaries that cannot remotely be characterized as fable. In over twenty years of providing valuation services in connection with ESOP installations, plan year updates and plan terminations, we have assisted many victims of bad advice and misinformation.

In recent years, Mercer Capital has seen a significant increase in the scrutiny of process and the propriety of conduct concerning ESOPs and their fiduciaries. In turn, Boards of Directors and ESOP Trustees (both inside and third party) are seeking more skilled and experienced service providers to enhance their understanding of the valuation process and to improve the credibility of their valuations. If you are an ESOP Trustee or a Board member of an ESOP-sponsor company, the ante for prudent decision-making continues to rise rapidly.

There are many reasons that ESOP valuation is an increasing concern for sponsor companies. Much has been written concerning Enron and other egregious cases of corporate malfeasance. As if greed was not bad enough to bring the hammer down, the demographic tsunami of plan participants requiring diversification or retirement is contributing to an inescapable tide of emerging liability issues. Compounding these concerns are the competing liquidity needs of non-ESOP shareholders who may be calling on finite resources to address their own needs. Last, but certainly not least, the economy is yawing and pitching in a storm of cyclical and fundamental waves which we have arguably never experienced. In the midst of all this turbulence, a strong dose of examination is required:

- Has the ESOP pool been examined for diversification and retirement needs? That next installment sale may be in direct conflict with meeting the needs of the existing plan participants. Liquidity at the company level may be required as a sinking fund for emerging liability issues. Absent such liquidity, borrowing capacity may be required to service the ESOP as opposed to redeeming the next shareholder desiring liquidity. Are you the fabled ant or the grasshopper? When it comes to ESOPs, preparation today is mandatory for the needs of tomorrow.

- Has the company experienced volatile and/or declining performance? How has the valuation report changed to reflect any such impact on value? Remember, the valuation is ultimately the responsibility of the Trustee. The appraiser is essentially an advisor whose work the Trustee must be able to understand, scrutinize, and ultimately promulgate as his/her own opinion of value. While hindsight always brings previously unrealized clarity, appraisers and Trustees must be able to comprehend the future implications of changing financial performance and position. While expectations can change and certain things are unknowable, appraisers and Trustees must not be guilty of fable by either omission or commission. Do not let the ESOP valuation constitute the flattery of the fox that bluffed the cheese from the crow. In the context of changing conditions, do not let your ESOP valuation report become a fable as it seeks consistency with past reports and downplays the severity of a real threat. Shortsighted gains and procrastination will ultimately come back to haunt shareholders and ESOP participants.

- Does the valuation report provide a reconciliation with prior opinions? Does the appraiser provide adequate support and/or discussion for changes in methods and/or critical assumptions from one report to the next? Does each annual report stand on its own while also reflecting the evolution of reporting and analytical standards?

- Is the relative illiquidity (by way of a marketability discount) of a minority ESOP appropriate in light of the sponsor company’s financial health and the plan?

- Does the valuation reflect a valuation adjustment to capture the so called "ESOP Benefit"? Careful scrutiny must be given to potentially controversial adjustments that could distort the value.

- Were excess premiums applied in the valuation of a control ESOP? These adjustments can be tantamount to writing checks that the company simply cannot cash. Over-valuation can plague an ESOP sponsor company and have serious ramifications for participants and selling shareholders.

Revisiting some of Aesop’s fables, we can find many relevant morals concerning the structuring and planning of an ESOP.

- They who act without sufficient thought, will often fall into unsuspected danger.

- In avoiding one evil, care must be taken not to fall into another.

- Precautions are useless after the crisis.

- It is best to prepare for the days of necessity.

- It is thrifty to prepare today for the wants of tomorrow.

- An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

- False confidence is the forerunner of misfortune.

This brief article cannot possibly provide a complete inventory of items and issues that may be important to assessing the health of an ESOP or the prudence of its sponsor company and fiduciaries. If your answers to some of the above questions have you concerned or curious, take action to prevent or correct potential problems. Mercer Capital has been providing valuation services on behalf of ESOP Trustees for over twenty years. Contact us to discuss a valuation need in confidence.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital's ESOP Valuation Advisor- Volume 13, No 1, 2004.

ESOP Ownership in S Corporations

Many of Mercer Capital’s clients have recognized the value of employee ownership in terms of employee loyalty and motivation as well as the numerous tax advantages to the business and maintain an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (“ESOP”). During the first part of 2001, we have performed hundreds of appraisals for purposes of establishing the value of shares held by ESOPs, proposed ESOP transactions as a result of mergers and acquisitions, and many other purposes. The most interesting development in the ESOP arena, however, is the increasing number of S corporations establishing ESOPs and ESOP-owned C corporations electing to convert to subchapter S status.

Although the provisions of the Small Business Protection Act of 1996 (the “Act”) enabled trusts such as an ESOP to be an S corporation shareholder, the Act included numerous provisions that presented significant barriers for S corporations to sponsor an ESOP. In 1997, however, Congress amended the Act to correct technical flaws relating to ESOPs. Most importantly, the revisions to the Act exempt ESOPs from the unrelated business income tax (“UBIT”), making ESOP ownership much more appealing. The revisions also allow S corporations to require cash distributions rather than stock distributions to departing employees to prevent potential disqualification of the subchapter S status (for example, an IRA is not a qualified S corporation owner, and an employee’s placing of S corporation stock in her IRA would result in the termination of S status under the Internal Revenue Code).

The valuation on S corporation stock is fundamentally identical to the valuation of an interest in a C corporation. However, a number of valuation approaches require the tax-effecting of earnings/distributions, an adjustment that will convert S corporation operations to a C corporation equivalent basis.

For example, the market approach to valuation includes a variety of methods that compare the subject company with transactions involving similar investments, including publicly traded guideline companies. A direct comparison between an S corporation and a publicly traded C corporation, however, is impossible, as demonstrated in the example in Table 1 top of page 2.

The S corporation’s hypothetical value based on $100 in pretax income and an after tax valuation multiple of 6x is $600, versus the C corporation’s value of $360. Say your company operated as a C corporation in 1998, operated as an S corporation during 1999, and operations were absolutely identical in both years. I am sure that you would agree that your Company’s value (everything else being equal) did not increase more than 65% simply because of the conversion to an S corporation. The flaw in the above analysis is, of course, the application of an after-tax multiple (which is commonly based upon publicly traded C corporations) on S corporation earnings. In order to allow for a meaningful comparison between your S corporation and the publicly traded C corporations, it is necessary to adjust the S corporation’s income for corporate taxes. On a C corporation equivalent basis, net income in the above example is $60 ($100 of taxable income tax-effected at an assumed tax rate of 40%), resulting in a value of $360 for the enterprise.

A similar adjustment is necessary when comparing a C corporation’s dividends with an S corporation’s distributions. C corporation shareholders pay income taxes at their applicable tax rate on dividends received. The S corporation shareholder, however, is responsible for the taxes on his or her share of the company’s income, whether a distribution occurred or not. As a result, it is necessary to convert distributions from an S corporation to a C corporation equivalent basis before any valuation inferences can be drawn. (For a more detailed description, please call us for a copy of “Converting Distributions From ‘S’ Corporations and Partnerships to a ‘C’ Corporation Dividend Equivalent Basis,” by J. Michael Julius, 1996).

The above examples illustrate that an S corporation’s value cannot be derived simply by applying after tax valuation multiples to S corporation net income or distributions. Similarly, we pointed out that there is no S corporation premium resulting simply from the conversion to a subchapter S corporation. If there is no increase in value as a result of conversion, however, what triggered the recent surge in conversions to S corporations?

The key incentive for ESOP ownership of an S corporation appears to be the fact that distributions to the ESOP are tax exempt. The higher the ESOP’s ownership stake in the company, the less taxes are paid. If the ESOP is the sole owner of the S corporation, the organization pays no income tax. While we demonstrated that an S corporation’s value does not differ from its C corporation peer, this ability to retain, accumulate, and reinvest significant amounts of cash can increase value over time as the operations and earnings grow. During the past year, some of our clients have been able to significantly expand their operations by using the incremental cash flow that resulted from their conversion to an S corporation.

At the same time, there are some potential disadvantages to the S corporation ESOP. First, a Section 1042 “Rollover” (the deferred recognition of gain on the sale of stock to an ESOP) is not available to S corporations. Second, contribution limits for S corporations to pay ESOP debt are limited to 15% of payroll (but increases to 25% if the ESOP contains money pension purchase provisions). Third, S corporations can only have one class of stock, and any distributions must be made pro rata. Since most S corporations distribute an amount at least equal to the shareholders’ tax liability and the ESOP has no tax obligation, funds that could be available for reinvestment have to be distributed to the ESOP. However, these funds could be used for a variety of purposes, including ESOP debt retirement, additional stock purchases, or payments to terminated employees.

C corporations with ESOPs desiring conversion to S status must also consider the following:

- S corporations must operate on a calendar year.

- The number of shareholders is limited to 75 (the ESOP counts as one shareholder, no matter how many participants).

- Subchapter S election requires the consent of all shareholders.

- Some fringe benefits paid to 2% or more owners are taxable.

- S corporations using last in, first out (“LIFO”) accounting on conversion are subject to a LIFO recapture tax.

- The sale of assets is subject to a built-in gains (“BIG”) tax on that sale for a period of ten years after conversion.

- Net operating losses incurred as a C corporation are suspended while an S corporation but may be applied against the LIFO recapture tax and/or the BIG tax.

- ESOPs may be subject to state unrelated business income tax in some states.

ESOP ownership in S corporations can create significant advantages for employers and employees. Employee ownership creates incentives for employees to contribute to “their” company’s success and motivate stakeholders to take an active part in the operations of the organization. Business owners have the opportunity to share the successes of their business with employees and reward loyal, long-time employees for their contributions to the business. While employee ownership provides many intangible advantages as compared to more traditional ownership structures, the ability of ESOPs to own a stake in an S corporation may very well be one of the most financially rewarding changes in tax legislation.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s ESOPVal.com, Volume 10, Number 1, 2001.

The DOL And ESOP Oversight Responsibility

Valuation and Procedural Prudence Issues

Mercer Capital has been engaged periodically by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to review an historical ESOP transaction and offer our comments regarding the appropriateness of (1)Valuation and (2) Procedural Prudence. While these are two different and distinct areas, the DOL is interested in pursuing both. Violations of procedural prudence can influence the business valuation process and its determination of adequate consideration for ESOP shares.

Proposed regulations for the Department of Labor relating to the adequacy of consideration paid in ESOP transactions have been outstanding since May 1988. Pending their finalization, many appraisal firms, including Mercer Capital, are operating as if they were final. In essence, the proposed regulations incorporate the guidelines of Revenue Ruling 59-60 and add other specific requirements for the appraisal of employers’ securities for ESOP purposes.

Valuation Issues

We do not provide legal advice, and would look to legal counsel to interpret the standards of fiduciary responsibility in the pension plan context, a primary objective of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). Nonetheless, a few general guidelines, based upon our experience, will highlight the need for professional advisors in the establishment and maintenance of an ESOP.

Does the valuation follow the basic guidelines of revenue Ruling 59-60, which sets the standard for Fair Market Value?

Does the valuation properly account for the degree of control to be purchased or sold by the ESOP: a minority or controlling interest?

Does the math check out?

Does the appraisal make sense?

Does that complex discounted cash flow model tucked in the back, and upon which substantial weight was placed, make sense when comparing future growth rates of sales, earnings and margins with historical results? Does the model reasonably reflect the risks of achieving those results? Are the reasons which support the model adequately disclosed in the text?

Do the guideline companies appear reasonably comparable to the subject company, or has the appraiser used multi-billion dollar sales companies in comparison to a $10 million family enterprise? Is the “fundamental discount” so large as to put the whole guideline approach into question?

Business valuation is an art as well as a science, and sometimes a company appraisal will not fit the normal standard to which the appraiser is comfortable. Appraisers and fiduciaries need to review appraisal reports to ensure that the premise, format and standard match the unique circumstances of the ESOP company.

Procedural Prudence Issues

Have fiduciaries reviewed and critiqued an independent appraisal report? As stated in Donovan v. Cunningham (716 F.2d 1455 (1983)), “An independent appraisal is not a magic wand that fiduciaries may simply wave over a transaction to ensure that their responsibilities are fulfilled. It is a tool and, like all tools, is useful if used properly. To use an independent appraisal properly, ERISA fiduciaries need not become experts in the valuation of closely held stock – they are entitled to rely on the expertise of others. However, as the source of the information upon which the experts’ opinions are based, the fiduciaries are responsible for ensuring that that information is complete and up-to-date.”

Have fiduciaries acted in good faith? There is a clear conflict of interest between the selling, controlling shareholder, who may also be President of the company, and the ESOP. This conflict should be mitigated by the input of other professional advisors.

Have the fiduciaries negotiated independently on behalf of the ESOP, in terms of transaction price, loan requirements and the structure of the deal?

Is there only one person who controls the whole process? There is an inherent conflict of interest if only one person is selling the shares, hiring the appraiser, providing the appraiser with company information and negotiating with the lending authority.

Did the appraiser receive full and adequate information? Most of what an appraiser can analyze is historical information, from which he can make a judgment about the future, based upon management performance. The appraiser must be advised how the future may change relative to the past, and how management will deal with or implement that change.

Are there clear lines of communication with responsible fiduciaries? Do they know their responsibilities and is it documented? Do the fiduciaries have the capacity to review the independent appraiser’s report and determine its adequacy?

Has the ESOP purchased or sold its shares for “adequate consideration” and can the reasonableness of that determination be validated by more than waving the appraisal report over the transaction?

Based on our experience, ESOP transactions are not always challenged by the DOL just because a participant complained. The DOL has periodically undertaken targeting initiatives to probe for violations of ERISA relating to whether ESOPs were independently valued, and whether that valuation supported the standard of adequate consideration.

If you would like to discuss a prospective ESOP transaction with us in confidence, please give us a call.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s ESOPval.com – Vol. 9, No. 2, 2000.

ESOPs: The Basics and the Benefits

An ESOP is an employee benefit plan designed with enough flexibility to be used to motivate employees through equity ownership. Therefore, according to theory, ESOPs implicitly enhance productivity and profitability and create a market for stock. This enhances shareholder liquidity and provides a vehicle for the transfer of ownership, which can assist in the transition from an owner/management group to an employee-owned management team.

Although ESOPs have been in use for a number of years – and with each new tax law undergo some changes – their basic structure and benefits have stood the test of time. ESOPs deserve to be examined and considered for potential application. Here is a brief and basic description of ESOPs, a simplified overview of the two types of ESOPs and a summary of the benefits of employee ownership to employees, shareholders and employers.

An ESOP Defined

An ESOP is an employee benefit plan which qualifies for certain tax-favored advantages under the Internal Revenue Code (“Code”). In order to take advantage of these tax benefits, it must comply with various participation, vesting, distribution, reporting and disclosure requirements set forth by the Code. These requirements are designed to protect the interests of the employee owner. ESOPs are also subject to the regulations set forth in the Employee Retirement and Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”) which essentially created a formal legal status for ESOPs and must meet the employee benefit plan requirements of the Department of Labor.

How An ESOP Works

A company establishes an employee stock ownership trust and makes yearly contributions to the trust. These contributions are either in new or treasury stock, cash to buy existing shareholder stock or pay-down debt used to acquire company stock. Regardless of the form, the contributions are tax-deductible.

Employees or ESOP participants have accounts within the ESOP to which stock is allocated. Typically, the participant’s stock is acquired by contributions from the company – the employees do not buy the stock with payroll deductions or make any personal contribution to acquire the stock. Plan participants generally accumulate account balances and begin the vesting process after one year of full time service. Contributions, either in cash or stock, accumulate in the ESOP until an employee quits, dies, is terminated, or retires. Distributions may be made in a lump sum or installments and may be immediate or deferred.

ESOPs are of two varieties: leveraged and non-leveraged. Each of the ESOPs has different characteristics.

Non-Leveraged ESOPs

FunCo, Inc. establishes an ESOP and makes annual contributions of cash, which are used to acquire shares of the company’s stock, or makes annual contributions in stock. These contributions are tax deductible for the company. As shares are allocated to participants’ accounts based on a value determined by an independent appraisal, employees begin to acquire an equity ownership in the business.

The employee/participant begins to vest according to a schedule incorporated into the ESOP document, and stock accumulates in the account until the employee/participant leaves the company or retires. At that time, the participant has the right to receive stock equivalent in value to his or her vested interest. Typically, ESOP documents contain a provision called a “put” option, which require the Plan or the company to purchase the stock from the employee after distribution if there is no public market for it, thus enhancing the liquidity of the shares.

Non-leveraged ESOPs, although they have certain tax advantages, generally tend to be an employee benefit, a vehicle to create new equity, or a way for management to acquire existing shares.

Leveraged ESOPs

Leveraged ESOPs tend to be more complicated than non-leveraged ESOPs. However, they provide a company with tax-advantages by which it can generate capital or acquire outstanding stock. A leveraged ESOP may be used to inject capital into the company through the acquisition of newly issued shares of stock.

FunCo establishes an ESOP. A bank or other lending institution lends money to the ESOP which acquires company stock. The company makes annual tax deductible contributions to the ESOP, which in turn repays the loan. Stock is allocated to the participants’ accounts – just as it is in a non-leveraged ESOP – enabling employees to collect stock or cash when they retire or leave the company.

Benefits Of An ESOP

The advantages and benefits of an ESOP are numerous and varied depending on whether you are the employee/participant, an existing shareholder, or an employer.

The Benefits To Employees

An ESOP can provide an employee with significant retirement assets if the employee is employed by the company for a significant period of time and the employer stock has appreciated over the years to retirement. The ESOP is generally designed to benefit employees who remain with the employer the longest and contribute most to the employer’s success. Since stock is allocated to each employee’s account based on a contribution by the company, the employee bears no cost for this benefit.

Employees are not taxed on amounts contributed by the employer to the ESOP, or income earned in that account, until they actually receive distributions. Even then, “rollovers” into an IRA or special averaging methods involved in the income calculation can reduce or defer the income tax consequences of distribution.