Jane Z. Astleford v. Commissioner

The case of Astleford v. Commissioner1 is noteworthy for a number of reasons. For instance, the Court’s ruling provides further support for applying tiered discounts in asset holding entities, and not only were the discounts tiered but they were also significant on each level applied, resulting in total blended discounts of approximately 55% with respect to certain assets. Additionally, in the determination of the appropriate lack of control (i.e., minority interest) discounts, the Court made use of data pertaining to both REITs that were publicly traded and RELPs that were traded on secondary markets. The Court also made use of studies cited in an expert’s report to justify discounts that were more than twice those applied by the expert.

Facts and Circumstances

After M.G. Astleford, a real estate investor, passed away in 1995, his wife, Jane Z. Astleford (Taxpayer), created the Astleford Family Limited Partnership (AFLP) in 1996. After transferring property to the AFLP, she gifted a 30% limited partnership (LP) interest to each of her three children (the 1996 AFLP interests), and retained a 10% general partnership (GP) interest. In 1997, Taxpayer transferred additional properties to the AFLP including a 50% GP interest in Pine Bend Development Co. (Pine Bend). As a result of this transfer, Taxpayer’s GP interest in AFLP increased significantly. In order to return Taxpayer’s GP interest to 10% of AFLP, Taxpayer gifted to each of the three children additional LP interests (the 1997 AFLP interests) necessary to return the ownership structure to the initial 30/30/30/10 allocation.

The Court outlined three general issues to be addressed in its ruling:

- The value of 1,187 acres of Minnesota farmland

- Whether a particular interest in a general partnership held by the AFLP should be valued as a partnership interest or an assignee interest, and

- The lack of control and lack of marketability discounts that should apply to the limited and GP interests.

This article will summarize the first two issues briefly, and then address the third issue, which deals with valuation discounts, in greater detail.

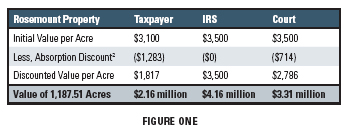

Issue #1 – Determine the value of 1,187 acres of Minnesota farmland (Rosemount Property)

The Taxpayer’s expert and the IRS expert each used a market approach by reviewing sales of similar properties.

According to the Court, the IRS expert was “particularly credible, highly experienced and possessed a unique knowledge of farm property located in the county in which the subject property was located.” The court used his initial value of $3,500 per acre.

However, the IRS appraiser did not apply an absorption discount to this value. The Court determined that an absorption discount was appropriate, but not to the extent applied by the Taxpayer’s appraiser. Using present value mechanics and making assumptions with respect to the holding period, discount rate, and appreciation rates, the Court applied an effective absorption discount of about 20%. The discounted price per acre was $2,786.

Issue #2 – Determine whether 50% GP interest in Pine Bend (held by the FLP) should be valued as a GP interest or an assignee interest

The Taxpayer’s appraiser argued that it should be valued as an assignee interest. As such, he discounted the interest because under Minnesota law a holder of an assignee interest would have an interest only in the profits of the partnership and would have no influence on management.

The IRS appraiser argued that the “substance over form doctrine” should apply, and therefore, the interest should be valued as a GP interest.

The court adopted the “substance over form doctrine” and rejected the Taxpayer’s argument; however, as discussed below, the Court applied a combined lack of control and lack of marketability discount of 30% to the Pine Bend interest, consistent with the Taxpayer’s appraiser’s methodology.

Issue #3 – Determine the lack of control and the lack of marketability discounts that should apply to the limited and GP interests

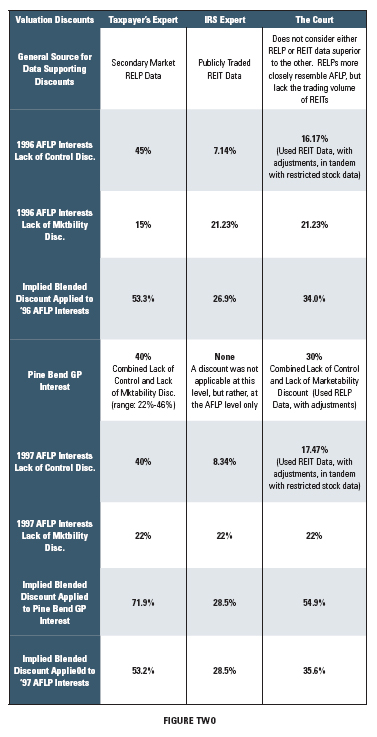

Figure Two summarizes the discounts applied by the Taxpayer, the IRS, and the Court.

Lack of Control Discounts Applied to AFLP Interests

The Taxpayer. The Taxpayer’s expert relied upon RELP secondary market data to determine that the lack of control discounts applicable to the 1996 and 1997 gifts of AFLP Interests were 45% and 40%, respectively. The RELP data, which reflected a group of four selected RELPs, provided a range of discounts of 40% to 47%. It is unclear how the Taxpayer’s expert determined that the lack of control discount applicable to the 1996 interests was greater than that applicable to the 1997 interests.

The Court noted that two of the four selected RELPs were more leveraged than AFLP. In addition, AFLP’s distribution yield of 10% was greater than the 6.7% average yield of the RELP group. The Court considered these two factors to be indicative of a lack of control discount less than that reflected in the RELP pricing. Due to these differences, among others, the Court concluded that the RELPs selected were “too dissimilar to AFLP to warrant the amount of reliance [the Taxpayer’s] expert placed on them” and the discounts for lack of control were excessive.

The IRS. The IRS expert relied upon REIT data to derive discounts for lack of control. The REIT data, which included approximately 75 REITs, indicated that the selected group traded at a median premium of 0.1% in 1996 and a median discount of 1.2% in 1997.

The Court explained that REIT prices are “in part affected by two factors, one positive (the liquidity premium) and one negative (lack of control).” The Court went on to say that liquidity premiums should be reversed out of the trading prices so as to determine the embedded discount for lack of control.3

The IRS expert used a regression analysis to determine that REITs traded at a liquidity premium of 7.79% relative to closely held partnership interests. Based upon this liquidity premium and the 1996 REIT group median premium of 0.1% and the 1997 REIT group median discount of 1.2%, the IRS expert calculated discounts for lack of control of 7.14% and 8.34% in 1996 and 1997, respectively.4

The Court. The Court ultimately decided to use the REIT data presented by the IRS expert to determine the appropriate lack of control discount, but the Court deemed the 7.79% liquidity premium offered by the IRS expert to be “unreasonably low.” Accordingly, the Court sought to calculate a more reasonable liquidity premium by calculating the difference in “average discounts observed in the private placements of registered and unregistered stock.” The Court considered any such difference as representative of “pure liquidity concerns.” Using this methodology, the Court referenced two studies cited by the IRS expert which indicated that a general premium for liquidity in publicly traded assets was on the order of 16.27%. Based upon this observed premium and the REIT group premium of 0.1% in 1996 and discount of 1.2% premium in 1997, the Court concluded that the discounts for lack of control in 1996 and 1997 should be 16.17% and 17.47%, respectively.5

Lack of Marketability Discounts Applied to AFLP Interests

Little explanation was provided with respect to the marketability discounts applicable to the gifts of AFLP interests.

The following relates to the 1996 AFLP interests:

[The Taxpayer’s] expert estimated a discount of 15%, and [the IRS] expert estimated a discount of 21.23%. We perceive no reason not to use [the IRS’s] higher marketability discount of 21.23% without further discussion, which we do.

The following relates to the 1997 AFLP interests:

Because both parties advocate a lack of marketability discount of approximately 22%, we apply a lack of marketability discount of 22%.

Combined Lack of Control and Lack of Marketability Discounts Applied to Pine Bend GP Interest

The Taxpayer’s expert relied upon data regarding 17 RELPs to determine a range of discounts of 22% to 46%, and he then selected a 40% discount without fully explaining the selection of that measure over the midpoint of the range or some other measure. The IRS appraiser did not apply any discount, as he claimed that any such discounts should be applied at the AFLP level only.

The Court rejected the position of each appraiser and performed its own analysis of RELP data. The Court concluded that a 30% combined discount for lack of control and lack of marketability was appropriate at the Pine Bend level, providing further support for applying tiered discounts in asset holding entities.

Summary and Conclusions

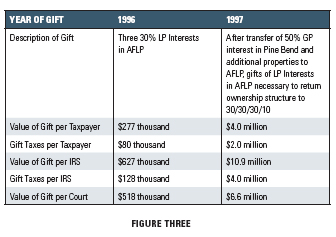

Figure Three summarizes the valuation conclusions reached by the Taxpayer’s expert, the IRS’s expert, and the Court.

As shown, the Court’s opinion fell within the range defined by the conclusions of the experts representing the Taxpayer and the IRS, with a slight overall bias towards the Taxpayer’s expert.

Observations

The Court’s application of an absorption discount appears to be well-grounded in present value mechanics using seemingly reasonable assumptions. Further, the general application of valuation discounts to not only the FLP interests but also the GP interest held by the FLP seems to be supported by valuation theory. However, the Court’s reliance on RELP and REIT data to determine the lack of control discount to be applied to AFLP interests is questionable.

In general, the price-to-NAV ratios observed in the REIT and RELP marketplace often reflect a numerator (price) which is current and a denominator (NAV) which is more dated. A REIT’s NAV may be determined once per year (usually at year-end) while market prices are determined by trading activity throughout the year. Under this system, some properties held by a REIT may experience rapid and unexpected appreciation in June, but NAV would still reflect the appraised values as of the preceding December, resulting in an understated NAV measure, all else equal. In this case, the price-to-NAV ratio may indicate the REIT is trading at a substantial premium to NAV due to the understated measure used in the denominator.

More meaningful valuation discounts may be derived using investment classes that have NAV measures which are updated throughout the year. One example is closed-end funds. In our experience, closed-end funds (equities and bonds) frequently trade at a discount to NAV between 0% and 15%. These discounts may be interpreted to represent a discount for lack of control.

Finally, the Court relied upon two studies (cited in the IRS expert’s report) in the determination of a liquidity premium. We note that these studies make use of equity market data (registered and unregistered stock information). The Court selects the liquidity premium implied in the equity markets and applies it to a FLP holding real estate. In a sense, the Court seems to have assumed there is only one liquidity premium for all asset classes in the marketplace. The Court uses this liquidity premium in tandem with the price-to-NAV ratios of REITs to calculate the resulting discount for lack of control for the AFLP interests. Intuitively, there appears to be a disconnect between REIT market pricing and the premiums paid for registered versus unregistered equity interests.

Endnotes

1 Jane Z. Astleford v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2008-128, filed May 5, 2008

2 The Court’s absorption discount was based upon assumed market absorption over a four-year period, a discount rate of 10%, appreciation of 7% per annum, sales expenses of 7.25%, and property taxes of 60 bp. Taxpayer’s expert made similar assumptions, but applied a discount rate of 25% (rather than 10%).

3 With respect to REIT data, discounts and premiums are based upon the ratio of price to NAV.

4 The relevant formula is: (1 + Liquidity Prem.) x (1 – LOC Discount) = (1 + Disc. or Prem. to NAV). Using 1997 as an example: (1.0779) x (1 – LOC Discount) = 0.988. (1 – LOC Discount) = 0.9166. Lack of Control Discount = 8.34%.

5 For 1996: 16.27% – 0.1% = 16.17%. For 1997: 16.27% + 1.2% = 17.47%.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Added™, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2008

The Estate of Charlotte Dean Temple

The Estate of Charlotte Dean Temple in United States District Court (No. 9:03 CV 165(TH) was adjudicated on March 10, 2006. This was a civil action for recovery of federal gift taxes and related interest. Plaintiff Arthur Temple (“Temple”) individually and as executor of the estate of his wife, Charlotte Dean Temple paid gift taxes on various gifts during the period 1997 – 1998 which upon audit were deemed to be undervalued. Temple paid the assessments and filed claims for a refund.

There were four entities at issue in this case: Ladera Land, Ltd (“Ladera Land”); Boggy Slough West, LLC (“Boggy Slough”); Temple Investments, LP; and Temple Partners, LP (collectively the “Temple Partnerships”). All four entities were asset holding entities: one LLC and three partnerships, all appropriately valued based on the underlying net asset value approach. As the Court saw it, “A critical factor in this case is determining the appropriate diminution in value between a hypothetical willing buyer and a hypothetical willing seller.” In other words, the key analytical factors in dispute were the prospects for a minority interest discount and a marketability discount.

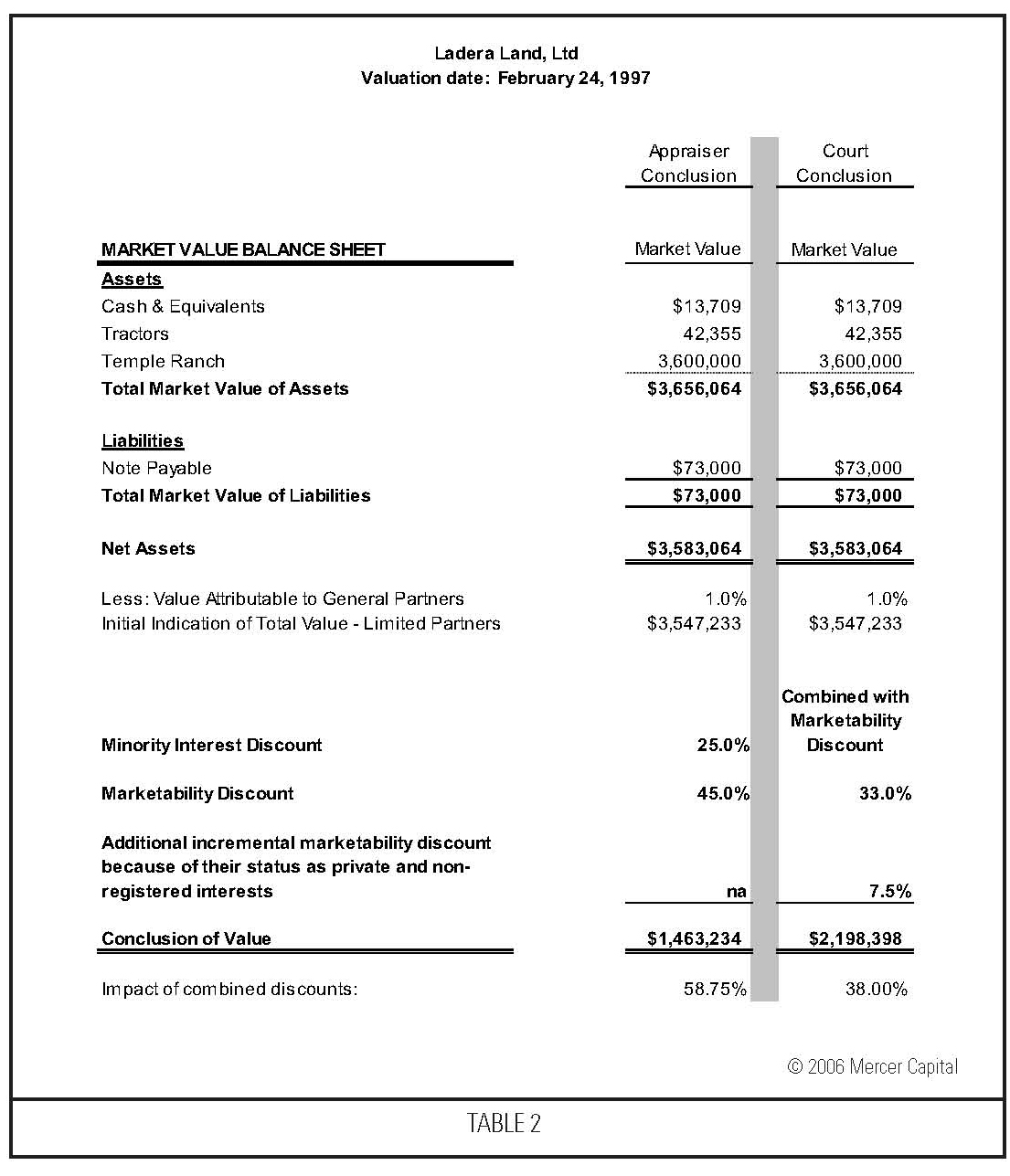

Ladera Land

For an analysis of the appropriate discounts for Ladera Land, Temple engaged the services of appraiser Nancy M. Czaplinski. Net asset values do not appear to have been in dispute. Czaplinski utilized the net asset value approach to this entity, although the Court chided her for discussing the appraisal only with Temple’s attorney, and not with any principals of the entity.

Minority Interest Discount

Czaplinski selected a 25% minority interest discount, based on “the inverse of the premium for control”, which in turn was derived from Mergerstat data. Czaplinski testified in court that the Mergerstat data is a study of operating companies but that she classified Ladera Land as a holding company.

Marketability Discount

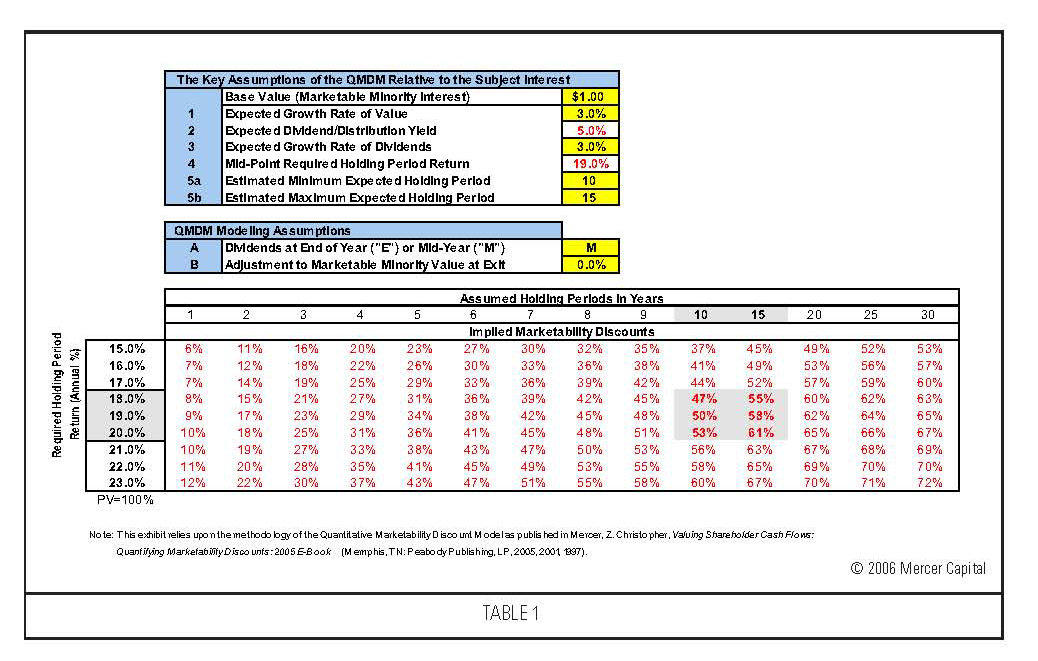

Czaplinski utilized the Quantitative Marketability Discount Model (QMDM) to assess the lack of marketability discount for Ladera Land. She assumed the following input items to implement the QMDM: 1) the holding period of a Ladera Land partnership interest is between 10 and 15 years; 2) the minority investor requires a holding period return on investment of 18-20%; 3) Ladera Land’s distribution yield is 5%; and 4) the expected appreciation of Ladera Land’s real property is 3%. These parameters provide a range of marketability discounts from 47% to 61%, as shown in Table 1.

The Court was unconvinced on several assumptions, but not on the applicability of the model. The 5% yield assumption was made without talking to anyone at Ladera Land, and the entity was not making distributions (although the assumption of a 5% yield would tend to reduce, rather than increase, the marketability discount). The expected property appreciation at 3% was based on conversations at Czaplinski’s own firm, not based on real estate appraisals. The Court did not understand the concept of the prospective holding period, saying “…the Court finds that it is inappropriate to assume a particular holding period for the hypothetical buyer” since there is no holding period requirement for the partnership interest.

It is on this last point that the Court missed the mark. As securities analysts, we make investment decisions in the marketplace every day, based on prospective holding periods. Life insurance policies are priced based on actuarial tables which clearly imply a holding period; corporate bonds are often priced at “yield-to-maturity” which thereby captures the current distribution yield as well as the implicit gain from a discount from par to maturity at par value. If you don’t hold it until maturity, you don’t get that full yield. Tax law recognizes holding period distinctions in the segregation of short-term gains from long-term gains. Common stock investors manage stock portfolios according to business, product cycle or interest rate cycle moves, with an investment time horizon in mind that dictates the relative mix of the portfolio.

In the case of closely held common stock, the analyst must make a reasonable assumption with regard to a prospective holding period; i.e., not necessarily until the termination of the partnership, but until that future date when some liquidity event occurs that may feasibly convert a security interest into cash. During that interim period, the investment has a security interest growing at some internal growth rate and possibly distributing some cash along the way. But a longer time horizon (holding period) implies a larger marketability discount, other things being equal.

The Court’s Conclusion

Lacking specific testimony at the valuation date with regard to alternative minority interest discounts, the Court did not specify a minority discount. Rather, it combined the minority and marketability discounts into a single 33% discount for the limited partnership interests, and combined that with an “additional incremental marketability discount because of their status as private and non-registered interests.” It is unclear how private and unregistered interests are distinguished from those impacted by the 33% marketability discount. Clearly, the Court was getting beyond its grasp in the application of this separate, ill-defined discount. The overall result is shown in Table 2.

Boggy Slough West, LLC

For an analysis of the appropriate discounts for Boggy Slough, Temple also employed Czaplinski, who utilized the same assumptions as in Ladera Land, also without discussing the appraisal with management. She concluded a 25% minority interest discount and a 45% marketability discount, again utilizing the QMDM. The Court echoed its concern over the assumptions in the QMDM, but had additional testimony from another expert, William J. Lyon, who testified about the difficulties in partitioning the underlying properties. Based on this additional input, the Court concluded that “Lyon’s valuations support Czaplinski’s calculations”, at least in the gift of larger interest. For four smaller gifts to grandchildren, the Court defaulted to its 38% overall discount as shown in Table 3.

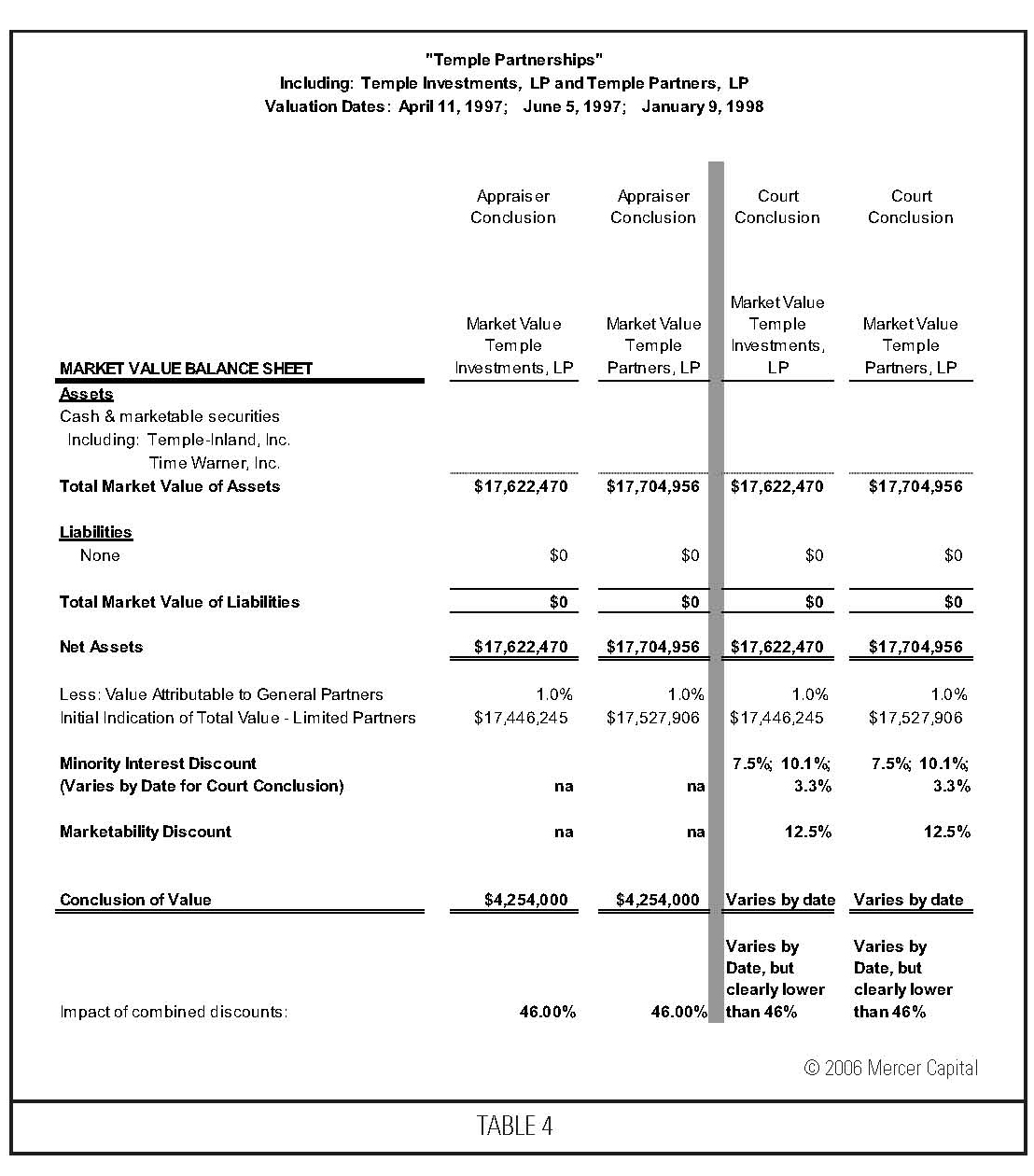

Temple Partnerships

The Temple Partnerships include Temple Investments, LP and Temple Partners, LP, both asset holding partnerships owning marketable securities in public companies. For the assessment of appropriate discounts for these entities, Temple engaged Mr. Charles Elliott, and the government expert was Mr. Frances Burns. Details in the case write-up are sketchy with regard to the minority and marketability discounts, however, the Court favored the Burns approach.

Minority Discount

Burns relied on a published weekly list of closed end funds, which showed discounts or premiums to net asset value. He did not exclude any funds, and calculated the mean discount at the three valuation dates, showing that the discount varied by date: 7.5%, 10.1% and 3.3%. Elliott had excluded some funds without explanation. The Court concluded that “Burns properly examined transactions involving closed end funds” and the minority interests corresponded to the published mean discounts to net asset value. “This method was used by the Tax Court in Peracchio v. Commissioner, 86 T.C.M. (CCH) 412 (2003). The Court observed that this was ‘an approach we have previously followed in the context of investment partnerships … and we shall do so again here.’ “

Marketability Discount

The QMDM was not utilized for the Temple Partnerships by either appraiser. In the determination of the marketability discount, Burns considered and relied upon seven factors: 1) restricted stock studies; 2) academic research; 3) the costs of going public; 4) secondary market transactions; 5) asset liquidity; 6) partnership interest transferability; and 7) whether distributions were made. By contrast, Elliott used restricted stock sales but did not analyze them as fully as Burns. Rather than taking restricted stock sales and explaining its relation to the gifted interests, Elliott simply listed the studies and picked a discount based on the range of numbers in the studies. The Court concluded: “The better method is to analyze the data from the restricted stock studies and relate it to the gifted interests in some manner, as Burns did.” The Court accepted the 12.5% marketability discount derived by Burns. The summary results are shown in Table 4.

Summary Comments

Minority Interest Discount

The Court here and with reference to prior cases has concluded that minority interest discounts (for investment companies) based on transactions involving closed end funds is an acceptable method. They focused on the mean as the statistical measure of central tendency. The median can also be useful, since it is not as distorted by extreme data at either end of the spectrum. The concept on both data bases is identical.

Marketability Discount

The Court is still struggling with this issue, and as jurists, cannot be expected to have a complete grasp of investment analysis. In the Temple case, they defaulted to the restricted stock studies, although concluding that the better approach was to “analyze the data” from the restricted stock studies to ensure applicability to the subject case. The Court appeared to be moving away from restricted stock studies in Peracchio, although it is clear overall that the Court is seeking more relevant analysis that it can apply directly to the facts and circumstances of a particular case.

At Mercer Capital, we have carefully reviewed the restricted stock studies and concluded that the dissection of academic studies into homogeneous sub-groups that can be applied with confidence to a particular case is not a helpful approach. The determination of a marketability discount is an investment decision, not an academic one, and it is necessarily based on investment facts and assumptions. These facts and assumptions include: competing rates of return for alternative investments; the growth rate of the underlying asset during the holding period; the expected dividend yield; the growth rate of the dividend; and yes, an expected holding period until some prospective liquidity event. As appraisers, we must deal with incomplete information all the time and base our analysis on the facts as we know them and on assumptions that are reasonable and defensible.

The QMDM fulfills the Court’s demand for analysis, and provides a framework for making a reasonable investment decision that can be applied to the facts and circumstances of a particular case. Facts are a key part of this, but so are the assumptions, some of which can be based on relevant market data and some of which must be based on a discussion with management. Again, in the end, it’s an investment decision, not an academic one. In the Temple case, the Court did not dismiss the QMDM, it just had a problem with the appraiser’s assumptions; and it missed the important perspective of the holding period as a necessary component of any investment decision.

At Mercer Capital, we have used the QMDM to assess the prospects for a marketability discount for over 10 years. It forces us as securities analysts to consider the facts and circumstances of an individual case and make an informed investment decision. Please give us a call if we may help you in your investment decision process.

When Is Fair Market Value Determined? Estate of Helen M. Noble v. Commissioner

Estate of Noble v. Commissioner was filed on January 6, 2005.1 In a 30 page decision, the Court gave short discussion to the reports of two experts, rather, focusing the decision on a discussion of a sale of the subject block some 14 months after the date of death (the valuation date). Two important issues are raised by Noble.

- The relevance of post-valuation date transactions or events (“subsequent events”) in determining the fair market value of non-publicly traded interests; and,

- The meaning of the concept of “arm’s length transactions” in the context of determinations of fair market value.

This article addresses both issues in the context of Noble and within one appraiser’s understanding of the meaning of fair market value.

Case Background

The subject of the valuation was 116 shares of Glenwood State Bank (“the Bank”), representing 11.6% of its 1,000 shares outstanding at September 2, 1996 , the date of death of Helen M. Noble (“the Estate”). Glenwood State Bank was a small ($81 million in total assets), over-capitalized (17.5% equity-to-assets ratio), low-earning bank (3% to 5% return on equity for the last four years) located in rural Glenwood , Iowa . Historical growth of the balance sheet had been anemic prior to the valuation date, and prospects for future growth were similar. Management’s philosophy, implemented over many years, was to reinvest all earnings back into the Bank and to pay no shareholder dividends. There was no market for the Bank’s shares.

The Estate’s 11.6% block of the Bank’s stock was the only block of the Bank that Glenwood Bancorporation, the parent holding company (“the Company”), did not own at the valuation date. The Company had, over a period of many years, gradually consolidated its ownership of the Bank to this point. The Company’s historical philosophy had mirrored that of the Bank, and no dividends were paid historically or anticipated for the near future.

In short, the subject 11.6% interest in the Bank was not a very attractive investment, when viewed in terms of then-current expectations for growth, dividends, and overall returns for publicly traded bank shares.

Two appraisals were submitted to the Tax Court in this matter:

- Internal Revenue Service. William C. Herber of Shenehon & Company (“Herber”) presented a valuation which concluded that the fair market value of the subject 11.6% interest in the Bank was $1,100,000, or $9,483 per share. The marketable minority value concluded by Herger was $13.1 million, and his marketability discount was 30%.

- The Estate. Z. Christopher Mercer, ASA, CFA of Mercer Capital (“Mercer”, the writer of this article) presented an appraisal which concluded that the fair market value of the subject interest was $841,000, or $7,250 per share. The marketable minority value concluded by Mercer was $12.7 million, and his marketability discount was 43%.

In addition, Glenwood State Bank had obtained an appraisal from Seim, Johnson, Sestak & Quist, LLP, an accounting firm, of the fair market value of the same shares as of December 31, 1996 (“the Seim Johnson Report”). This report concluded that the fair market value of the shares was $878,004 ($7,569 per share).

The Estate originally reported the fair market value of the shares at $903,988 ($7,793 per share based on then-current book value less a minority interest discount of 45%).

One more fact is important for this introduction. The Estate sold its 116 shares to Glenwood Bancorporation on October 24, 1997 , almost 14 months after the valuation date, for $1,100,000.2

Focusing on the expert reports of Herber and Mercer, the total difference in value between the two appraisals of the 11.6% interest was $259,000. Herber’s result was about 30% higher than Mercer’s. Relative to many valuation disputes, the differences were fairly small. Both appraisers agreed on the relative unattractiveness of the subject shares as an investment. Herber’s appraisal represented 73% of the Bank’s book value, while Mercer’s appraisal represented 56% of book value.

The major difference in valuation conclusions between the two appraisers was the difference in their concluded marketability discounts. This was an opportunity for the Court to address these differences in a meaningful way; however, that did not occur. We present information here not found in the opinion to inform the reader of the rest of the story.

Relevance of Subsequent Events

After discussing two sales of minority interests of the Bank’s stock, one of which occurred some 15 months prior to the valuation date (at $1,000 per share), and the other of which occurred about two months prior to the valuation date ($1,500 per share), the Court’s decision notes:

As to the third sale, which occurred on October 24, 1997, approximately 14 months after the applicable valuation date, we disagree with petitioners that only sales of stock that predate a valuation date may be used to determine fair market value as of that valuation date. The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, the court to which an appeal of this case most likely lies, has held specifically that “In determining the value of unlisted stocks, actual sales made in reasonable amounts at arm’s length, in the normal course of business, within a reasonable time before or after the basic date, are the best criterion of market value.”3 [citations omitted, emphasis added]4

No mention is made in the Court’s decision as to what constitutes a “reasonable time” before or after a valuation date. The Court goes on to say, after further discussion of the subsequent transaction, that:

When a subsequent event such as the third sale before us is used to set the fair market value of property as of an earlier date, adjustments should be made to the sale price to account for the passage of time as well as to reflect any change in the setting from the date of valuation to the date of sale. [citing Estate of Scanlan5] These adjustments are necessary to reflect happenings between the two dates which would affect the later sale price vis-à-vis a hypothetical sale on the earlier date of valuation. These happenings include: (1) Inflation, (2) changes in the relevant industry and the expectations for that industry, (3) changes in business component results, (4) changes in technology, macroeconomics, or tax law, and (5) the occurrence or nonoccurrence of any event which a hypothetical reasonable buyer or hypothetical reasonable seller would conclude could affect the selling price of the property subject to valuation (e.g., the death of a key employee [citing Estate of Jung6].

The record before us does not establish the presence of any material change in circumstances between the date of the third sale and the applicable valuation date. [emphasis added]7

The Court noted that the 116 shares sold for a total of $1.1 million, or $9,483 per share, on October 24, 1997 . In response to the above guidance regarding “the happenings between the two dates” the Court stated: “While the record does not accurately pinpoint the appropriate rate to apply for that purpose [inflation], the Bureau of Labor Statistics has stated that the rate of inflation during each of the years 1996 and 1997 was slightly less than 3 percent.”

The five factors noted above are now considered:

- Inflation. The Court did its own independent research on inflation, lowering the subsequent transaction price to $1,067,000 ($1,100,000/(1 + 3%)). This reduction of $33,000, or $284 per share, was made by the Court to account for the effect of inflation during the period between the valuation date and the date of the subsequent transaction despite specific expert advice arguing against the appropriateness of this adjustment for the change in inflation.8

- Changes in the Relevant Industry and the Expectations for that Industry. The Court made no investigation of changes in industry expectations. However, the banking industry experienced very strong results in the public markets between September 2, 1996 and October 24, 1997 , with the NASDAQ Bank Index increasing some 75% over the period. This compared with a 45% increase in the S&P 500 Index over the same period. So the base market evidence used by both appraisers would have shown considerably higher price/earnings multiples and price/book multiples 14 months later. This certainly could have had an influence on value at the time of the subsequent sale. Clearly, consideration of the change in market conditions could have had a significant impact on value during the interim period, and should be taken into account if one is considering a subsequent transaction as direct evidence of fair market value as of an earlier date. The Court did not do this, citing the absence of such post-valuation date evidence in the record. Were the appraisers somehow at fault for not discussing post-valuation date market performance? More frequently, appraisers are criticized for engaging in such analysis.

- Changes in the Business Component Results. The Court made no investigation of changes in business component results. However, it is clear from the record that the Bank was earning at the rate of about $700,000 per year and paying no dividends to shareholders, so just over a year later, its book value would have been about $700 per share higher. This foreseeable change, which was noted in the Mercer Report, was not considered by the Court.

- Changes in Technology, Macroeconomics, or Tax Law. The Court did no investigation of changes in these factors. Suffice it to say that there were almost certainly changes in one or all of these areas.

- The Occurrence (or Nonoccurrence) of Events that Reasonable Investors Would Consider Impact Value. The Court did consider the subsequent sale of 116 shares of Glenwood State Bank by the Estate. However, the Court did not consider another subsequent event which occurred virtually simultaneously with the subsequent transaction, that materially changed the value of the 116 shares of Glenwood State Bank. The parent company, Glenwood Bancorporation, decided that it wanted the Bank to pay dividends after many years of not paying dividends. As discussed in the Mercer Report, there was a strong aversion to paying dividends from the Bank to the Company. This change of philosophy would also have changed the amount that Glenwood Bancorporation was willing to negotiate for a transaction for the 116 shares of the Bank’s stock. Immediately after the transaction, when the Company owned 100% of the Bank’s shares, a dividend of $1,200,000, or $1,200 per share on the previously-outstanding 1,000 shares was paid (between October 24, 1997 and December 31, 1997). This dividend, if received by the Estate as a continuing shareholder, would have represented a yield of 12.7% based on the subsequent transaction price of $9,483 per share. As was discussed in the Mercer Report and in Mercer’s trial testimony, this change had the effect of creating a significant change in the value of the shares relative to September 2, 1996 .9

Neither Mercer nor Herber provided an analysis of events in the stock market, in the market for bank stocks, or of detailed financial performance of Glenwood State Bank subsequent to the valuation date. Both appraisers were providing valuation opinions as of September 2, 1996 . Mercer mentioned the subsequent transaction in his report, and both appraisers mentioned the transactions prior to the valuation date. The Mercer Report discussed the subsequent change in dividend policy in detail.

It should be clear from the above analysis of the factors mentioned by the Court, that there were material changes, virtually all positive regarding the value of 116 shares of Glenwood State Bank, between the valuation date of September 2, 1996 and the subsequent transaction on October 24, 1997.

The Court’s analysis of subsequent transactions raises several questions:

- If one is to consider a subsequent transaction directly in an appraisal as of a specific date, what is a “reasonable time” for consideration of that transaction? Evidently, 14 months was “reasonable” to the Court. What about two years? Or three years or more?

- When is a valuation ever over?

- Is there a need for a revaluation in light of the five guidance factors above every time appraisers encounter subsequent transactions?

- What is an appraiser who is valuing a business or business interest as of a current valuation date to do regarding subsequent transactions that have not occurred when he or she is rendering the opinion?

- Is it reasonable to impeach an appraisal done timely based on transactions that occur subsequent to the valuation date? After all, neither the appraiser conducting such a timely appraisal nor hypothetical or real willing buyers and sellers would have had knowledge of that such subsequent events.

- Do real-life investors have the opportunity for such a free look-back?10

- Is the consideration of subsequent events as “evidence of fair market value” as of an earlier date merely a way for an appraiser or a court to reach a pre-determined conclusion?

- The underlying question is, what kind of analysis does the Tax Court desire in a determination of fair market value as of a given valuation date?

It is my understanding of the investment process that investors consider all relevant information, including that which is known and that which is reasonably foreseeable, or reasonably knowable, up to the moment that an investment is executed. After that, there are no second chances. Real-life investors know that one of only two things will happen with respect to the return performance of any particular investment:

- It will perform at less, equal to, or greater than the original expectations over the expected investment horizon; or

- The actual investment horizon will be shorter or longer than original, expected investment horizon, and performance will be equal to, less than or greater then original expectations.

The investment’s ultimate performance will be the (net) result of many factors, including the actual performance of the underlying entity, changes (favorable or unfavorable) in national economic conditions or specific industry conditions, the general level of the stock markets and the particular performance of a particular industry, and the other factors noted above.

The Court’s decision in Noble causes great uncertainty for both appraisers and taxpayers.

Arm’s Length Transactions

A Four-Factor Test for Bargaining Parity

The second fundamental issue in Estate of Noble relates to the nature of arm’s length transactions. This writer understands the nature of the standard of value known as fair market value to consist of:

- A hypothetical willing buyer and a hypothetical willing seller (presumably independent of each other),

- Both of whom are fully (or at least reasonably) informed about the subject of investment,

- Neither of whom is acting under any compulsion,

- And both of whom have the capacity to engage in a transaction involving the subject interest,

- Engage in a hypothetical transaction at the fair market value (cash-equivalent) price.

A transaction involving these characteristics would be an “arm’s length” transaction in the context of fair market value. Fair market value transactions presume bargaining parity. Note from this definition that an actual transaction in nonpublicly traded stock would not meet the definition of arm’s length transactions in the context of fair market value if one or more of the following four conditions of bargaining parity are not met:11

- Independence . If parties are related in some way, it is clear that transactions between them should be viewed with skepticism. It is simply not possible to know the extent of relationships or how those relationships could impact the pricing of a particular transaction.

- Reasonably and Equally Informed. If both parties are not reasonably (equally) informed about the facts and circumstances related to the investment, a transaction should also be viewed with skepticism. Clearly, if one party has a significant information advantage over the other, a transaction is not likely to occur at fair market value, since the party lacking the information lacks equal bargaining power. As will be shown below, the Court did not consider a known inequality of information with respect to the third transaction which should have excluded it from consideration as evidence of fair market value at any time.

- Absence of Compulsion. If one or both of the parties is acting under any compulsion to engage in a transaction, it is generally understood that a transaction is not evidence of fair market value. A party acting under compulsion would lack parity in bargaining power relative to the party who can view the investment opportunity dispassionately and objectively.

- Financial Capacity to Transact. If one party lacks the financial capacity to engage in a transaction, the results of negotiations may not reflect equal bargaining power.

It will be helpful to review the concept of arm’s length transactions in the context of these four essential elements of bargaining parity, i.e., through the four factor test outlined above. Although this test was not employed explicitly in this manner in the Mercer Report, it was employed implicitly in the discussion and analysis of the three transactions.

The Court’s Analysis of Three Transactions

The Court paraphrased Polack v. Commissioner12 and Palmer v. Commissioner13 in introducing its discussion of arm’s length transactions:

While listed stocks of publicly traded companies are usually representative of the fair market value of that stock for Federal tax purposes, the fair market value of nonpublicly traded stock is “best ascertained” through arm’s-length sales near the valuation date of reasonable amounts of that stock as long as both the buyer and the seller were willing and informed and the sales did not include a compulsion to buy or to sell.14

While this guidance is flawless as far as it goes, it needs to be viewed, as just indicated, through the filter of the four factors of bargaining parity.

The Court’s decision discusses three transactions in the stock of Glenwood State Bank, the two occurring before the valuation date and the subsequent transaction some 14 months after the valuation date. The Court determined that the two prior sales were not at arm’s length:

As to the two prior sales of stock in this case, we also are unpersuaded that either of those sales was made by a knowledgeable seller who was not compelled to sell or was made at arm’s length.15

The Court actually made two additional comparisons in reaching its conclusion regarding the two prior sales. First, the decision notes that they were both smaller in size (1% or less of the shares) than the subject interest (11.6%). And second, it was noted that neither of these two transactions was made based on an appraisal.

The Court discussed the subsequent transaction at some length at this point:

Petitioners try to downplay the importance of the subsequent (third) sale of the estate’s 116 Glenwood Bank shares by characterizing it as a sale to a strategic buyer who bought the shares at greater than fair market value in order to become the sole shareholder of Glenwood Bank. Respondent argues that the third sale was negotiated at arm’s length and is most relevant to our decision. We agree with respondent. Although petitioners observe correctly that an actual purchase of stock by a strategic buyer may not necessarily represent the price that a hypothetical buyer would pay for similar shares, the third sale was not a sale of similar shares; it was a sale of the exact shares that are now before us for valuation. We believe it to be most relevant that the exact shares subject to valuation were sold near the valuation date in an arm’s length transaction and consider it to be of much less relevance that some other shares (e.g., the 10 shares and 7 shares discussed herein) were sold beforehand. The property to be valued in this case is not simply any 11.6% interest in Glenwood Bank; it is the actual 11.6-percent interest in Glenwood Bank that was owned by decedent when she died. [emphasis added]16

It would appear that the Court determined that because the same 116 shares sold 14 months after the valuation date for $9,483 per share, they were therefore worth the same $9,483 per share (less a discount for inflation) at the date of death some 14 months prior.

In reaching this conclusion, the Court did something that both appraisers warned against, in effect, assuming that the exact transaction that occurred was foreseeable.17,18 There is a world of difference in the relative risk assessment by hypothetical willing buyers and sellers between two different situations: 1) it is reasonably foreseeable that a transaction will occur at a specific price and at a specific time in the future; or 2) it is generally foreseeable that a transaction, or a variety of potential transactions, could occur at some unknown and indefinite time (or times) in the future. The Court’s analysis effectively assumed the first situation existed at the valuation date when, in fact, the second situation existed. In doing so, the Court ignored the risks of the expected investment holding period from the perspective of hypothetical buyers and sellers at the actual valuation date.

The Court also did not believe that Glenwood Bancorporation had specific motivation to purchase the shares which would cause it to pay more at the subsequent date.

Moreover, as to petitioners’ argument, we are unpersuaded by the evidence at hand that Glenwood [Bancorporation] was a strategic buyer that in the third sale paid a premium for the 116 shares. The third sale was consummated by unrelated parties (the estate and Bancorporation) and was prima facie at arm’s length. In addition, the estate declined to sell its shares at the value set forth in the appraisal and only sold those shares 5 months later at a higher price of $1.1 million. Although the estate may have enjoyed some leverage in obtaining that higher price, as suggested by Mercer by virtue of the fact that the subject shares were the only Glenwood Bank shares not owned by the buyer, this does not mean that the sale was not freely negotiated, that the sale was not at arm’s length, or that either the estate or Bancorporation was compelled to buy or to sell. 19

The Court is assuming that transactions occurring between unrelated parties provide prima facie evidence of their arms’ length natures. However, independence is only one of the four factors insuring bargaining parity and therefore, arms’ length transactions. The Court asked Mercer about the nature of this particular transaction. Mercer testified that while a transaction may appear to be at arm’s length, it should not be evidence of fair market value if there is an inequality of information regarding the potential transaction.20

Applying the Four-Factor Test of Bargaining Parity

Another Analysis of the Three Transactions

The Mercer Report provided background information for the two transactions prior to the valuation date as follows:

- One transaction involving seven shares occurred in July 1996 at $1,500 per share (approximately 11% of book value). The seller was Linda Green, the daughter of a long-time shareholder. Upon attempting to contact Ms. Green to discuss the circumstances of her sale of stock, we learned that she had died within the last year.

- Another transaction occurred in June 1995 when a director of the Bank sold ten shares for $1,000 per share. The price represented approximately 8% of December 31, 1994 book value. Management indicated that the director, Mr. Robert Hopp, desired to turn his non-dividend paying stock in the Bank into an earning asset and offered it to the Bank. The agreed upon price was $1,000 per share. Bank management stated that they knew of no compulsion to sell on Mr. Hopp’s part (financial or otherwise) and that he remained a director of the Bank until his death several years later. As a director, we should be able to assume that Mr. Hopp was reasonably informed about the Bank and the outlook for its performance, as well as about prior transactions in the stock. We were unable to contact Mrs. Hopp to discuss her recollection of the circumstances of the transaction; however, we have no reason to question the recollections of the Bank’s chairman.

The Mercer Report also discussed the subsequent transaction at some length, and analyzed it in light of the facts and circumstances in existence at the subsequent transaction date, at least as they related to Glenwood State Bank and Glenwood Bancorporation. As noted above, the Mercer Report indicated that a significant change in policy would have materially changed the value of the subject 116 share block. Glenwood Bancorporation, after many years of not desiring to upstream dividends from Glenwood State Bank, changed its mind. The reason for this change was a decision to build a new bank in Council Bluffs , Iowa , to enter the greater Omaha metropolitan market. This decision required capital that was lying dormant in the Bank, and would require that significant dividends be paid by the Bank to the Company. Importantly, Glenwood Bancorporation did not inform the Estate’s representatives of this change in policy prior to the transaction. So the second factor of the four-factor bargaining parity test was not met. This was noted in the Mercer Report.

The Mercer Report did indicate that such a change in dividend policy could occur at Glenwood Bancorporation (i.e., was reasonably knowable); however, the analysis indicated that no rational, independent investor would assume that the change would occur in such a short time as a year or so, and that if dividends were to be paid, there would be a material, upward pressure on the value of the Bank’s minority shares.

It is important to place this subsequent change in dividend policy in perspective. The following table, provided in the Mercer Report in the discussion of the subsequent transaction, should indicate clearly that if the dividend policy had been in place at the valuation date, the valuation conclusion should have been significantly higher than either the Mercer conclusion or the conclusion of the Herber Report or that of the Court based on the subsequent transaction.

As noted above in the discussion of the nature of subsequent transactions, something material changed between the date of death and the subsequent transaction. Glenwood Bancorporation decided that it desired to receive dividends from Glenwood Bank after many years of not having the Bank pay dividends. This change in policy necessarily had a change on the value of the Bank’s shares since, other things being equal, an investment that pays dividends is worth more than one that does not pay dividends.

The Court’s analysis does not mention the remaining, critical element of a fair market value transaction – that both parties be reasonably (and equally) informed about the investment. This is a point that Mercer addressed both in his direct testimony (report) and in cross-examination.

Given that the Estate sold 116 shares for $1,100,000 on October 24, 1997 , consider the following regarding equal and reasonable information:

- Did the Estate’s representatives know that, between that date and December 31, 1997 , Bancorporation would cause Glenwood State Bank to declare and to pay dividends totaling $139,200 on those very same 116 shares? Management of Bancorporation did not inform the Estate’s representatives of this fact or intention.

- Did the Estate’s representatives know that Bancorporation would declare and pay nearly $800,000 in dividends ($6,850 per share) on the Estate’s 116 shares between the sale date and the end of 2001? Management of Bancorporation did not inform the Estate’s representatives of this fact or intention.

- Following the payment of $6,850 per share in dividends over the next four years, the 116 shares owned by the Estate would have had a then (2001) book value of $12,648 per share (relative to the sale price in 1997 of $9,483 per share).

In fact, both the Seim Johnson and Herber Reports stated the following about the expectation of future dividends:

“Glenwood State Bank has not paid any dividends since May of 1984 and has indicated no intention to pay dividends in the near future. This decreases the value of the common stock, and, also, it adversely impacts a willing buyer’s decision to purchase the stock.” [emphasis added, Seim Johnson Report at page 7]

“As of September 2, 1996 , Glenwood State Bank had not paid a dividend in over a decade and had no plans to pay dividends in the future.” [Herber Report, page 15]

These valuation reports, prepared just shortly after the date of death (Seim Johnson) and much later (Herber), affirm the stated policy of the Bank that was provided to Mercer Capital during interviews held in 2004. They also affirm the fact that there was a significant change in policy between the date of death and the time of the third transaction some 14 months later.

The point of this discussion is that there was a material change of facts between the valuation date and the subsequent transaction and this change of facts was known to only one of the two parties to the transaction. This causes the subsequent transaction to fail the four factor bargaining parity test and disqualifies the transaction as an arm’s length transaction in the context of a determination of fair market value. In fact, had the change of policy been known, it is almost certain that the subsequent transaction would have occurred at a price substantially higher than the actual price of $9,483 per share.

The four-factor bargaining parity test is summarized for the three transactions below.

It would appear that the prior transaction involving Mr. Hopp, the former director of Glenwood State Bank, would meet the four-factor test. It occurred at a very low price (relative to book value) at a time when a knowledgeable, independent buyer had no expectations of future dividends or other avenues to liquidity within a reasonable timeframe.

It is simply unknown if the second prior transaction meets the four-factor test.

But it is clear that the subsequent transaction does not meet the test. The parties were clearly not equally informed about the change in dividend policy that Glenwood Bancorporation planned to implement immediately following the transaction.

So the question is, how can a subsequent transaction that would not pass the four-factor test for arm’s length bargaining parity at the date it occurred provide evidence of the fair market value of shares some 14 months prior to that date? In the opinion of this writer, it cannot.

The Court considered that the sale was negotiated at arm’s length as prima facie evidence that the subsequent transaction was evidence of fair market value. However, it should be clear from the analysis above, which was presented to the Court in the Mercer Report, that there was a material change of circumstances between the date of death the date of the subsequent transaction. It should further be clear that the parties engaging in that subsequent transaction were not dealing with the same information about the value of the subject interest.

Conclusions

Estate of Noble raises two very important issues for business appraisers:

- The relevance of subsequent transactions (or events in determinations of value as of a given valuation date

- The nature of arm’s length transactions in fair market value determinations

Should transactions (or events) occurring subsequent to a given valuation date be considered in the determination of fair market value as of that valuation date? If so, how should they be considered in the context of facts and circumstances in existence at the valuation date? How long after a given valuation date can information from a subsequent transaction be considered relevant? Opening the door to the routine analysis of subsequent transactions as providing evidence of valuation at earlier dates would seem to fly in the face of the basic intent of the fair market value standard of value.

Are transactions occurring between apparently independent parties prima facie evidence of arm’s length transactions in the context of fair market value? The four-way test of bargaining parity introduced above questions the relevance of at least certain otherwise arm’s length transactions as providing evidence of fair market value.

The questions and issues raised by Estate of Noble are important for appraisers and for taxpayers. Regarding subsequent transactions, it would seem that appraisers and the Tax Court should focus on events known or reasonably foreseeable as of the valuation date as the basic standard for fair market value determinations. Any other approach would seem to raise more questions than can be answered, and would seem to place at least one party in a valuation dispute at a distinct disadvantage.

Finally, regarding the nature of arm’s length transactions, it would seem that a more definitive understanding of the nature of “arm’s length” is needed than the mere fact that parties appear to be independent of each other. The four-way bargaining parity test above indicates that independence is only one of four factors needed to define an arm’s length transaction characterized by equal bargaining power.

1 Estate of Helen M. Noble v. Commissioner, T.C Memo. 2005-2, January 6, 2005.

2 In the final analysis, this fact was determinative of value in the Court’s decision. There was surprisingly little discussion of any of the three valuation reports before the Court in Noble.

3 The Herber Report did not mention the subsequent transaction. The Mercer report mentioned the subsequent transaction, but did not rely on it in reaching its appraisal conclusion. Herber’s conclusion, however, was identical to the value of the subsequent transaction. Mercer’s report analyzed the subsequent transaction and placed it into perspective with his valuation-date conclusion, indicating that circumstances had changed between the valuation date with respect to expected dividend policy at Glenwood Bancorporation (and therefore, with respect to Glenwood Bank). Mercer noted that while Glenwood Bancorporation knew of this change in policy, it was not communicated to the Estate’s representatives prior to the transaction.

4 Supra. Note 1, pp. 21-22.

5 Estate of Scanlan v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1996-331

6 Estate of Jung v. Commissioner, 101 T.C. at 431.

7 Supra. Note 1, pp. 28-29.

8 The Court asked Mercer a direct question on the appropriateness of discounting a subsequent transaction to the valuation date “at interest.”

THE COURT: Okay. Another question for you. I asked you earlier about the possible use of the October transaction as a potential for a valuation. If one wanted to look at that and factor in an interest rate what rate would you use in order to factor that in?

THE WITNESS: Well, let me answer it just one other – one slightly different way. If you look at our valuation, my valuation, that 841,000, and I understand that Mr. Herber’s problem with talking about I and we, because we do that as firms, and you apply a 17 percent rate of return you would get to about , oh, a million. The 1.1 million, the 1.14 years implies about a 25 of 26 percent rate of return. That would not be unusual for an earlier [than anticipated] transaction.

THE COURT: But you are looking at a rate of return. I am simply saying wouldn’t you just factor, couldn’t one just factor in an interest rate, in other words, like a discount rate for time value of money?

THE WITNESS: Well, no, because the fact of the matter is an interest rate for the time value of money would not include premium for the risk of holding the stock for that period of time. So at the very least if you were going to do that to reverse back to the present you would build up a discount rate to 16, 18, 20 percent, or 26 percent, or some number, and bring that back to the present. The time value of money would not account for that risk.

THE COURT: Okay.

THE WITNESS: When you buy stock now, you have the risk going forward, and you don’t know about the transaction.

9 Clearly, the conclusions of both appraisers would have been higher had there been any reasonable expectation of such dividends in the readily foreseeable future.

10 The answer to this question is “obviously not.”

11 Mercer Z. Christopher, Valuing Enterprise and Shareholder Cash Flows – the Integrated Theory of Business Valuation ( Memphis , TN : Peabody Publishing, 2004). These issues are discussed at some length in chapter 8: “Fair Market Value vs. the Real World.”

12 Polack v. Commissioner, 366 F.3d 608, 611 (8th Cir. 2004), affg. T.C. Memo. 2002-145.

13 Palmer v. Commissioner, 62 T.C. 684, 696-698 (1974).

14 Supra. Note 1, pp. 12-13.

15 Supra. Note 1, p. 20.

16 Supra. Note 1, p. 25.

17 Counsel for the Internal Revenue Service asked Mercer a series of questions regarding the third transaction. The last question and answer was:

Q. Right. And this stock was liquidated in slightly over one year.

R. Sure. Hindsight is 20/20. I’m saying that [it] is not a reasonably foreseeable event that in 1.14 years that the stock would be sold at the price it was sold at, in my opinion.

18 Mr. Herber, the expert retained by the Internal Revenue Service, was asked directly about whether he thought the third transaction was foreseeable:

THE COURT: Do you think that as of the valuation date that subsequent sale was foreseeable by a hypothetical buyer and seller?

THE WITNESS: No.

THE COURT: Why not?

THE WITNESS: Because of the facts that are talked about in the report. They had not paid dividends. They did not want to sell the bank. There was definitely – you could not foresee that specific transaction.

THE COURT: But could you foresee the fact that there would be some transaction with a period of time?

THE WITNESS: Oh, yes, yes.

19 Supra. Note 1, pp. 25.

20 The Court’s question was raised immediately following Mercer’s “20/20 hindsight” comment quoted in Footnote 17 above.

THE COURT: That sale, though, Mr. Mercer, as far as you know that was an arm’s-length sale?

THE WITNESS: Your honor, as far as I know it was an arm’s-length sale, but let me be careful to answer a little further. An arm’s-length sale does not necessarily provide evidence of fair market value even if the transaction occurs prior to the valuation date. An arm’s-length sale with compulsion is – that’s arm’s-length, but there is compulsion [and it] would not qualify as evidence of fair market value. An arm’s-length sale with lack of knowledge would not qualify as evidence of fair market value. And I’m suggesting that this transaction was an arm’s-length sale with lack of knowledge.

THE COURT: And specifically what was the lack of knowledge? I know you have testified earlier to it, but if you would repeat it, I would appreciate it.

THE WITNESS: That the relationship between Glenwood Bank Corporation [Bancorporation], the likelihood that dividends would be paid in the future, or that I would have a chance to negotiate for this a favorable sale. The existence of Glenwood Bank Corporation, we don’t know that anyone knew that Glenwood Bank Corporation even existed because the shareholders of the bank had no reason to know anything about it. They file separately to the Federal Reserve, you know, to the federal authorities.

And the only reason we know about it is because we asked. And when we asked about the holding company, then we looked at the historical financial statements of the holding company. Now to show you the relationship between the bank and the holding company and the lack of interest of this management in paying shareholder dividends prior to the valuation date, there was over $400,000 of debt at the parent company, Glenwood Bank Corporation. It would have been an easy thing to do to upstream a dividend to pay that debt.

Rather than do that and pay the dividend to the shareholder [the 11.6% that would go to the 11.6% interest holder in the Bank], they went and bought more stock in Glenwood Bank Corporation, putting $400,000 into Glenwood Bank Corporation and paying down that debt externally. That’s a fact. That would not give me a great deal of conviction that I was likely to get dividends any time real soon.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Matters™ 2005-02, March 4, 2005.

Estate of Stone: Victory for Family Limited Partnerships

The Family Limited Partnership (“FLP”) has been a common estate planning technique for the nation’s wealthy. For years it allowed families to avoid some tax liability when transferring assets to heirs by first placing those assets in a FLP. And for years the U.S. Tax Court ruled in favor of these tax-minimizing vehicles. The IRS responded by fighting those who might use the FLP to avoid paying taxes on the full and undiscounted value of their estate. While the IRS’s early opposition hinged on the valuation discount applied to FLP interests, recent cases have focused on the inclusion of a FLP’s underlying assets in a taxpayer’s estate via §2036.

Section 2036(a)(1) Defined

According to §2036: (a) General Rule.–The value of the gross estate shall include the value of all property to the extent of any interest therein of which the decedent has at any time made a transfer (except in case of a bona fide sale for an adequate and full consideration in money or money’s worth), by trust or otherwise, under which he has retained for his life or for any period not ascertainable without reference to his death or for any period which does not in fact end before his death– (1) the possession or enjoyment of, or the right to the income from, the property … [emphasis added]. The “bona fide sale” exemption is important to our topic today. In essence, a FLP must be operated as a real business opportunity to qualify for the “bona fide sale” exception.

A Brief History of Section 2036(a)(1) Challenges in the Tax Court

The IRS has raised a number of considerations in its recent challenges of FLPs. Such considerations include whether or not the taxpayer respected the FLP’s formality on both a formation and operational basis, whether or not the taxpayer contributed assets for personal use to the FLP, and whether or not the taxpayer maintained assets outside of the FLP sufficient to maintain a pre-FLP lifestyle.

The Estate of Thompson v. Commissioner (2002) illustrates the first success of the IRS.[1] The deceased created two FLPs, one for each of his children. The Tax Court, however, found that the deceased had retained benefits from the assets that he had transferred to the FLP. It rejected the family’s argument that the exchange for limited partner interests was a bona fide sale; instead, the Court deemed the transfer a “recycling of value.” Accordingly, the Tax Court stated that the asset contributions had “no legitimate business purpose” and held that the value of all the assets in the estate should be taxed at the full amount.

The next big win for the IRS came in the Appeals Court in Strangi II (2003).[2] Continuing its assault on FLPs in relation to §2036, the IRS found favor in the Appeals Court because the Tax Court found that the transferor continued to enjoy the benefits of the assets transferred and derived his economic support from the assets; thus, the Tax Court concluded that the FLP had no business purpose.

A third case that illustrates the success of the IRS is Kimbell v. US.[3] The IRS now had two strategic assault methods in its use of §2036. The first method focused on demonstrating that the FLP had no operational aspects, and the second method attempted to demonstrate that the FLP contained an “implied understanding” that the transferor would retain benefit or control of the assets. Because the deceased retained “legal right” in the FLP’s documents to control partnership assets, the Tax Court found that the FLP was in violation of §2036 and would pay taxes on the full value of the assets.

Estate of Stone – Taxpayer Victory

In spite of a series of victories, such as those summarized above, the IRS’ §2036 argument was not victorious in Estate of Stone.[4] In its November 7, 2003 decision, the Tax Court provided much needed clarity related to confusion surrounding §2036. Relevant background information includes:

- Five FLPs were formed several months prior to the deaths of Mr. and Mrs. Stone;

- At death, Mr. Stone held the majority of the general and limited partner interests in each of the FLPs;

- Each FLP held various assets, including real estate and preferred stock in the family-owned operating company;

- Each of the Stone children received small general partner interests in return for their respective contributions on the date of formation of the FLPs, while Mr. Stone retained sufficient general partner interest to hold a simple majority of the general partner interests in aggregate. Mrs. Stone held only limited partner interests;

- The estate tax returns claimed aggregate minority and marketability discounts of 43% on Mr. Stone’s interests; and,

- Four of the five FLPs had made non-pro rata distributions to the estate to pay Mr. Stone’s estate tax.

At first reading, the fact set in this case has similarities to the §2036 challenges raised in Thompson, Kimbell, and Strangi. These include death soon after formation of the FLP, distributions from the FLP used to pay the estate taxes, distributions that were not made on a pro-rata basis, retention of significant FLP interests, as well as retention of the controlling general partner interest.

As noted in the decision, “In order to resolve the parties’ dispute under §2036(a)(1), we must consider the following three factual issues presented in each of the instant cases:

- Was there a transfer of property by the decedent?

- If there was a transfer of property by the decedent, was such a transfer other than a bona fide sale for an adequate and full consideration in money or money’s worth?

- If there was a transfer of property by the decedent that was other than a bona fide sale for an adequate and full consideration in money or money’s worth, did the decedent retain possession or enjoyment of, or the right to income from, the property transferred?”[5]

As to the question regarding the transfer of property, the Court concluded “… that Mr. Stone and Ms. Stone each made a transfer of property under §2036(a).[6] As to question (2), the IRS argued that the transfer did not qualify under the bona fide sale exception, citing that the average 43% discounts claimed for tax purposes conflicted with the exception’s stipulations, which describe an exempt transfer as “a sale for adequate and full consideration only if that received in exchange is ‘an adequate and full equivalent reducible to money value.’”[7] Several facts which proved critical to the Tax Court’s approval of the transfers as bona fide sale exceptions included the following:

- Each member of the Stone family retained independent counsel and had input regarding the structure of the FLPs. However, Mr. and Mrs. Stone ultimately decided which, if any, assets would be transferred to each of the FLPs.;

- The Stones retained sufficient assets outside of the FLPs to maintain their accustomed standards of living;

- The transfers of issue did not constitute gifts by the Stones but instead were pro-rata exchanges;

- The primary motivation behind the transfers was investment and business concern related to the management of certain assets held by the Stones; and,

- The FLPs had economic substance and operated as joint enterprises for profit through which the children actively participated in the management and development of the respective assets.[8]

The Tax Court concluded that the transfers of assets by Mr. and Mrs. Stone to the FLPs were for adequate and full consideration in money or money’s worth. Furthermore, unlike in Estate of Harper, in which the Tax Court indicated that the creation of the partnerships was not motivated primarily by legitimate business concerns, the Court stated that the transfers executed by Mr. and Mrs. Stone failed to constitute unilateral recycling of value.[9]

As to question (3), because the transfers qualified under the bona fide sale exemption, the Tax Court deemed unnecessary the consideration of whether or not the decedents retained possession or enjoyment of or rights to income from the transferred property.

Conclusion

In spite of Thompson, Kimbell, and Strangi, among others, the FLP’s viability as an effective estate planning tool appears intact based on Estate of Stone. As stated earlier, a FLP must be operated as a real business opportunity to qualify for the “bona fide sale” exception and that seems to be the linchpin in these cases.u

Endnotes

1 Estate of Thompson – T.C. Memo. 2002-246 (September 26, 2002)

2 Estate of Strangi – T.C. Memo. 2003-145 (May 20, 2003)

3 Kimbell v. U.S. – No. 7:01-CV-0218-R, USDC ND TX., Wichita Falls Div. (January 14, 2003)

4 Estate of Stone v. Commissioner – T.C. Memo. 2003-309 (November 7, 2003)

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Estate of Harper – T.C. Memo. 2002-121 (May 15, 2002)

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Matters™ 2003-08, December 4, 2003.

Hackl v. Commissioner – A Valuation Practitioner’s Perspective

The Tax Court’s decision in Albert J. and Christine M. Hackl v. Commissioner1 has provoked a lively discussion about how to achieve discounts to net asset value and still qualify for the annual exclusion. We challenge the notion that obtaining deep discounts requires a host of restrictive provisions in the operating agreements. We also propose a broader definition of economic interest that includes the growth in value of underlying assets.

Case Summary

A.J. Hackl established a tree farm for the purpose of long-term growth (no pun intended). As he expected, it incurred losses in the first few years of operation. However, according to forestry consultants, Hackl managed the farm in a manner that would generate a steady income stream in the future.

Upon establishing the tree farm as an LLC, Hackl and his wife began to transfer ownership units to family members. On their tax returns, the Hackls treated these gifts as eligible for the annual exclusion. The IRS contested this classification, claiming that the transfers did not provide a present interest to the donees. To contain said interest, the gift must convey “substantial present economic benefit by reason of use, possession, or enjoyment of either the property itself or income from the property.”2

The Court ruled that the unusual restrictions in the operating agreement prevented the gifts from conferring a present interest. Specifically, the agreement granted the manager (A.J. Hackl) the authority to 1) appoint his own successor, 2) prevent withdrawal of capital contributions, 3) negotiate terms of resale of interests, and, most important, 4) prohibit any alienation or transfer of member interests. The Court focused not on the features of the interest gift, but on the underlying limitations on the interests being gifted. The Court employed a three-part test to determine whether income qualified for present interest: receipt of income, steady flow to beneficiaries, and determination of the value of that flow. Because the LLC did not make distributions in the first years of operation, the Court ruled that the donees received no enjoyment of income from the property.

Valuation Questions

Some believe that the abnormally restrictive operating agreement produced the Hackl result. If they are correct, then Hackl is an aberration that will have little effect on the construction of LLC agreements.

The reaction to Hackl presents the discount and the annual exclusion as an either/or proposition—i.e., the restrictions that produce deep discounts will deprive the recipients of the present interest required for annual exclusion. One observer concludes that estate planners must decide either to gift large interests at heavy discounts based on highly restrictive agreements or to dribble out value with annual exclusion gifts based on much less restrictive agreements.3

The other valuation issue concerns the definition of a present interest. The Court insists that, unless donees are receiving income distributions right now, their holdings contain no economic benefit today. Carried to its logical conclusion, this position says that only a portfolio of investment-grade fixed income securities has economic value at any given point in time.

Mercer Capital has certain strong beliefs on both of these issues. With regard to the restrictions in operating agreements, we maintain that analysts have constructed a false dichotomy between discounts and annual exclusion. It is possible to obtain both within the same gift. We would even cast doubt on the idea that unusually heavy restrictions guarantee any additional discounts beyond those contained in typical, “plain vanilla” agreements. The discounts for minority interest and lack of marketability derived from these latter type of agreements are substantial in size and indisputably eligible for annual exclusion. Furthermore, these discounts can be computed with high degrees of accuracy. How does one systematically determine the discount associated with a host of oddball provisions? And why would one, aware of the unfavorable tax consequences, endeavor such a calculation? LLC members gain nothing from restrictions that, in the process of deepening discounts, remove the present interest and disqualify the transfer for annual exclusion. While unusual restrictions may be necessary for the parties, they are not necessary for calculating discounts.

In defining present interest, we believe that economic benefit entails more than immediate distributions. In the case of Hackl, the tree farm was highly likely to turn a profit in the long-term. Using the income approach, appraisers take the quantity of that future income and convert it to a present value. An income stream tomorrow counts for an economic benefit today. In short, present interest should also entail growth in value—the benefits from the appreciation of an underlying asset’s worth during the holding period. Unless this concept is real, a portfolio of non-dividend growth stocks carries no value. The valuation community should put pressure on the narrow definition of present interest through solutions that explicitly incorporate growth in value into its appraisals.

A Crummey Approach