New York’s Largest Corporate Dissolution Case: AriZona Iced Tea

After several years of litigation involving a number of hearings and trials on various issues, a trial to conclude the collective fair value of a group of related companies known as the AriZona Entities (also referred to as “AriZona” or “the Company”), occurred. The trial was held in the Supreme Court, State of New York, Nassau County, New York, the Hon. Timothy Driscoll, presiding. The trial lasted from May 22, 2014 until July 2, 2014.1

The Court’s decision in what I will refer to as “the AriZona matter” (or “the matter”) was filed on October 14, 2014. I have not previously written about the AriZona matter because I was a business valuation expert witness on behalf of one side.2 I was asked not to publish anything while the matter was still pending. The parties recently closed a private settlement of the matter, so there will be no appeal.

There are numerous quotes from the Court’s decision in Ferolito v. Vultaggio throughout this article. However, in an informal article of this type, I will not cite specific pages for simplicity and ease of reading.

Background about the Case

The overall litigation had numerous complexities; however, the valuation and related issues were ultimately fairly straightforward. The Court had to determine the fair value, under New York law, of a combined 50% interest in the AriZona Entities as of two valuation dates. The first date, October 5, 2010, pertained to a portion of the 50% block, and the remainder of the block was to be valued as of January 31, 2010.

The Court’s decision focused on the first valuation date, or October 5, 2010, and we will do the same in this analysis of the case.

The case citation in the footnote below provides the names for all plaintiffs and defendants in the matter. For purposes of this discussion, we simplify the naming of the “sides” in the litigation, following the Court’s convention.

- The group of plaintiffs, led by John Ferolito, is referred to as “Ferolito” herein. I worked on behalf of Ferolito.

- Similarly, the group of defendants, led by Dominick Vultaggio, is referred to as “Vultaggio.”

Expert witnesses for Ferolito included Z. Christopher Mercer (Mercer Capital), Basil Imburgia (FTI Consulting), Dr. David Tabak (NERA Economic Consulting), Christopher Stradling (Lincoln International), and Michael Bellas (Beverage Marketing Corporation). Mercer was the primary business valuation expert. Imburgia testified on developing adjusted earnings for AriZona. Stradling, an investment banker, also testified regarding the value of AriZona. Finally, Bellas testified regarding the revenue forecast he developed for AriZona and that was employed by Mercer in the discounted cash flow method.

Expert witnesses for Vultaggio included Professor Richard S. Ruback (Harvard Business School and Charles River Associates), who was the primary valuation expert, and Dr. Shannon P. Pratt (Shannon Pratt Valuations). Pratt testified on the topic of the discount for lack of marketability but did not offer an independent valuation opinion. Other experts worked on behalf of Vultaggio, but their opinions received little treatment in the Court’s decision.

Background about the AriZona Entities

The AriZona Entities market beverages (principally ready-to-drink iced teas, lemonade-tea blends, and assorted fruit juices) under the AriZona Iced Tea and other brand names. At the valuation dates, the Company sold product through multiple channels, including convenience stores, grocery stores, and other retailers, primarily in the United States. International sales comprised about 9% of total sales.

The Company was founded in 1992 by Vultaggio and Ferolito, who each owned 50% of the stock at that time. It grew rapidly to the range of $200 million in sales and significant profitability and remained at that level until 2002, at which time sales began to rise rapidly and consistently, reaching about $1 billion in 2010.

Normalized EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization), as determined by Basil Imburgia on behalf of Ferolito, was $181 million for the trailing twelve months ending September 2010, which the Court accepted. While the text of the decision states that Imburgio’s EBITDA for that time period was $173 million and a table shows it as $169 million, Imburgio’s concluded EBITDA was, indeed, $181 million, which the Court accepted and Mercer accepted, as well.

Ruback’s estimate of EBITDA for calendar 2010 was $168 million. There was no disagreement over the recent strong earnings of AriZona.

AriZona was, at the valuation dates, an attractive, profitable and growing company that was gaining market share in the ready-to-drink (RTD) tea industry. It was the only private company in the $1 billion sales range in the non-alcoholic beverage industry in the United States. In the years and months leading to the valuation date, several very large companies, including Coca-Cola, Tata Tea, and Nestle Waters, held discussions with either Vultaggio and the Company, Ferolito, or both, regarding the potential acquisition of either the Company or the 50% Ferolito interest.

The Level of Value for Fair Value

Counsel for Ferolito interpreted fair value in New York as being at the strategic control level based on the following case law guidance:

“[I]n fixing fair value, courts should determine the minority shareholder’s proportionate interest in the going concern value of the corporation as a whole, that is, ‘what a willing purchaser, in an arm’s length transaction, would offer for the corporation as an operating business.'” 3

Mercer provided a conclusion of fair value at the strategic control level of $3.2 billion, which included the consideration of the sharing of certain expected operating synergies with hypothetical buyers. Stradling offered a conclusion of strategic control value in the range of $3.0 billion to $3.6 billion.

The Court did not consider that strategic value was appropriate for its determination of fair value. After citing several cases, including Friedman v. Beway Realty Corp. (“Beway”), the Court concluded:4

These principles make clear that the Court may not consider AriZona’s “strategic” or “synergistic” value to a hypothetical third-party purchaser, as Ferolito urges. A valuation that incorporates such a “strategic” or “synergistic” element would not rely on actual facts that relate to AriZona as an operating business, but rather would force the Court to speculate about the future.

Interestingly, the Court did not quote the language from Beway noted just above. What would a willing purchaser like Tata Tea, Coca-Cola, or Nestle Waters pay for AriZona? Whatever price these “willing purchaser[s], in an arm’s length transaction” would offer would certainly include consideration of potential synergies. I do not say this to argue with the Court’s conclusion, but to point out that the conclusion is not reconciled with the plain language of Beway.

The Court concluded that it would value the Company using the “financial control” measurement (as described by Mercer in the Mercer Report and in testimony at trial). However, that decision did force the Court to “speculate about the future” because the Court’s conclusion, which was based on Mercer’s discounted cash flow (DCF) method, employed a ten year forecast of revenues and expenses.

In anticipation of the Court’s decision regarding strategic control value, Mercer also provided conclusions of fair value at the financial control level. These values were $2.4 billion as of October 5, 2010 and $2.3 billion as of January 31, 2011.

The Ruback Report offered a standard of value that can be described as “business as usual.” 5

It is my understanding that, under New York law, the fair value of shares of Arizona Iced Tea values the company as a going concern operated by its current management with its usual business practices and policies.

No case law guidance was offered by Ruback for this “business as usual” standard, which included management’s inability or unwillingness ever to raise product prices.

The Ruback Report’s conclusion of fair value for 100% of AriZona’s equity was $426 million. The concluded enterprise value is well below 3x EBITDA.

In its decision, the Court concluded that consideration of expected synergies was speculative and did not consider Mercer’s conclusions at the strategic control level of value. The Court focused instead on Mercer’s financial control valuations. The Court rejected the “business as usual” standard offered in the Ruback Report.

The Court Focuses on Discounted Cash Flow

The Ruback Report took the position that the discounted cash flow method was the appropriate method for the determination of the fair value of AriZona.

Mercer applied a weighting of 80% to the DCF method. But Mercer and Stradling considered the use of guideline public companies and guideline transactions, as well. Mercer accorded the guideline public company indications with the remaining weight of 20%. Because of the substantial weight placed on the DCF method by Mercer, the difference in position was relatively minor.

The issue for the Court was one of comparability. Obviously, I thought the use of guideline public companies was relevant, and that the selected group of public companies was sufficiently comparable to provide solid valuation evidence at the financial control level. Nevertheless, the Court disagreed and focused solely on the discounted cash flow valuation.

The Court’s Determination of Fair Value

Having determined that the focus would be on the discounted cash flow method, the Court looked at the key components of the DCF methods employed by Mercer and Ruback. As noted, the Court’s starting point was the discounted cash flow analysis from the October 5, 2010 DCF method from the Mercer Report.

After concluding that Mercer’s DCF method was the starting point for analysis, the Court developed a very logical examination of the key components of the DCF analysis, providing sections reaching conclusions on the following assumptions:

- Revenue

- Costs

- Terminal Value

- Tax Amortization Benefit

- Tax Rate

- “Key Man” Discount

- Discount Rate

- Outstanding Cash, Non-Operating Assets, and Debt

- Discount for Lack of Marketability

In the following sections, we address each of these assumptions, although I have reordered them to facilitate the discussion.

The starting point is the DCF conclusion already includes one assumption made by the Court. In disregarding Mercer’s guideline public company method and its somewhat lower indicated value, the starting point for the Court’s analysis was increased by $79.2 million, or from $2.36 billion to $2.44 billion.

1. Anticipated Revenue

The Bellas Report provided a ten year forecast of expected future revenues for AriZona. He forecasted domestic revenues and provided a separate forecast for expected future international sales assuming a conscious effort on the part of the Company to focus on international sales, which comprised some 9% of revenues at the valuation date. The Court wrote:6

Based on the depth and breadth of Bellas’ experience, the significant research regarding the trends in the RTD industry and AriZona in particular, and his demeanor throughout this testimony, the Court credits Bellas’ testimony in its entirety regarding AriZona’s future revenues.

The Court provided a review of the Bellas Report’s analysis and my adoption of the analysis, concluding as follows:7

Upon relying on Bellas’ projections for AriZona’s domestic and international prospects, Mercer projected AriZona’s revenue to grow a compounded annual growth (“CAGR”) rate of 10.2%, which is consistent (and may well be conservative when compared to) AriZona’s CAGR from 2006-10 of 13.9%. The Court thus adopts Mercer’s revenue projections. In so doing, the Court notes Mercer’s impressive expertise in the field of business valuation, including (a) completing some 400 business valuation per year [that’s 400 for Mercer Capital, not Mercer], including a significant number of valuations exceeding $1 billion, (b) extensive business appraisal credentials, and (c) publication of over 80 articles regarding different valuation issues. By contrast, Ruback’s experience in business valuation is almost entirely academic in nature.

In the final analysis, the Court adopted the revenue projection of the Bellas Report which, in turn, was reviewed, analyzed and accepted for the Mercer Report.8 Revenues were forecasted to increase about 7.7%, rising from the last twelve months in September 2010 of $958 million to $2.0 billion in 2020.

Although the Bellas revenue forecast adopted by Mercer was deemed aggressive by the Vultaggio side, AriZona’s revenues were forecasted to reach $2.2 billion by 2020 in the Ruback Report.

2. Operating Costs

The Court observed that in the past, AriZona had been able to manage costs. The Court was presented information regarding historical cost of goods sold, operating expenses, and resulting EBITDA, both in dollar terms and in terms of the resulting historical EBITDA margins.

The Court noted that Mercer used past costs as a basis to forecast future costs. The Ruback Report assumed that future costs would rise faster than revenue, with resulting pressure on profit margins.

To make the point about the unreasonableness of the Ruback Report’s cost assumptions, the Court quoted a portion of my trial testimony:9

[Ruback] utilizes a business plan that I don’t believe has any bearing in history or any bearing in any evidence I have seen. He conducts – he assumes a business plan that basically assumes that Mr. Vultaggio and the management at AriZona are incompetent and [in]capable of adapting to evolving business conditions.

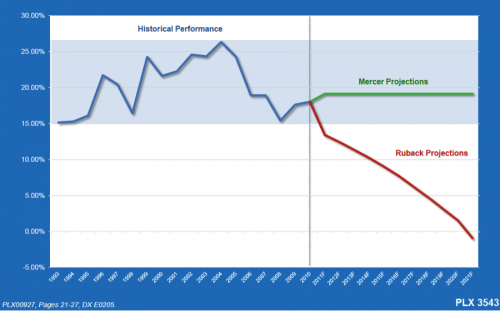

The Ruback Report made two critical assumptions that resulted in an unrealistic and unreasonable forecast of costs and the resulting impact on forecasted EBITDA and EBITDA margins. First, costs were projected to increase with expected inflation. Second, all prices were held constant over the entire projection period. The result was a precipitous drop in the forecasted EBITDA margin. A picture is helpful.

The chart below provides historical EBITDA margins and the forecasted margins employed in the Mercer Report (green) and the Ruback Report (red).

In the final analysis, the Court credited Mercer’s testimony regarding AriZona’s anticipated costs. In so doing, having already adopted its revenue forecast, the Court adopted the Mercer Report’s forecasted income for the ten year forecast period employed in that report.

3. Tax Rate Assumption

The Court did not, however, entirely adopt the forecasted net income and net cash flow of the Mercer Report. For some reason, the Court selected tax rates from the Ruback Report, which were the sum of the marginal personal rate and the marginal state rates, presumably because of AriZona’s S corporation status.

The Ruback Report assumed a personal marginal tax rate of 35%, an average state income tax rate of 4.5%, and a corporate tax rate of 4% for AriZona itself. These were added together, not accounting for the deductibility of state taxes for federal income tax purposes, and a tax rate of 43.5% was posited for the forecast.

The Court correctly noted that there was no explanation of the use of the blended federal/tax rate in the Mercer Report. I can only say that the usual table that illustrates the calculation of the blended federal and state tax rate was missing from the relevant valuation exhibits. Nevertheless, the investment bankers who provided testimony also provided blended federal/state rates similar to the 38% used in the Mercer Report. I did not have an opportunity to address this issue, either on direct or cross-examination during trial testimony.

It is fairly standard to begin the valuation of an S corporation on as “as if” C corporation basis. Then, if there are benefits that are additive to value for the S corporation, they can be considered separately. I valued AriZona on an “as if” C corporation basis and then separately considered the tax amortization benefit as being accretive to value for the Company.

Pratt, who testified for Vultaggio, agrees with this, as was pointed out in Part I of the Gilbert Matthews article series cited in endnote 2.

It is important to recognize that both C corps and S corps pay taxes on corporate income. Whether that tax is actually paid by the corporation or the individual is absolutely irrelevant. What is relevant is the difference between the value of a company valued as a C corporation…and [as] an S corporation. It is for this reason that most S corporation models begin by valuing the company “as if” a C corporation… and then go on to recognize the benefits of the Sub-chapter S election.10

All parties, including Stradling and the other investment bankers who provided opinions or whose work was introduced into evidence (except Professor Ruback) valued AriZona, which was an S corporation, as if it were a C corporation, because the likely buyers of the Company were publicly traded C corporations.

There has been an ongoing debate in the valuation profession regarding whether there should be a valuation premium accorded to an S corporation like AriZona relative to a similar C corporation. I have written and testified that an S corporation is worth no more than an otherwise identical C corporation. However, it is hard to find otherwise identical corporations for comparison.

What I have written is that there is no inherent increase (or decrease) in the value of enterprise cash flows whether their corporate wrapper is an S corporation or a C corporation. There are lots of things that can change the proceeds of a sale to a seller between the two types of corporations, including:

- An S corporation that retains earnings enables its owners to build basis in their shares, thus sheltering future capital gains taxes. The basis of ownership in C corporations remains at cost until the shares are sold.

- An S corporation’s assets can be sold, enabling the buyers to write up assets for future depreciation or amortization. This write-up and subsequent amortization provides a tax amortization benefit that can enable buyers to pay more for an S corporation. See the next section. In the alternative, the parties can elect a Section 338(h)(10) Election, which provides substantially the same effect as a purchase of assets.

- A C corporation may have embedded capital gains on assets that would be realized upon a sale of assets.

By raising the tax rate above the expected tax rates of likely buyers, the Court effectively lowered the DCF value in the Mercer Report by $196 million, or about 8%. This is simply an incorrect treatment, in my opinion from economic or financial viewpoints.

It is my understanding that the Court later requested additional information on the issue of appropriate tax rates for the valuation of an S corporation like AriZona. No one knows if a change might have been made because the matter has settled.

4. Tax Amortization Benefit

The Court did not agree with the consideration of a tax amortization benefit in the Mercer Report. The tax amortization benefit was calculated on the assumption that, in a hypothetical sale of AriZona as an S corporation (assumed to be structured as an asset sale), the write-up of intangible assets over the minimal tangible assets on the balance sheet would give rise to a tax amortization benefit to the buyer. The present value of this benefit was calculated over the 15 year amortization period allowed under then current tax law.

On cross-examination, I noted that I had not used such a benefit before in valuing an S corporation. However, I did note that this benefit had been a point of negotiation between the AriZona parties and Nestle Waters, and was included in valuation calculations leading to a $2.9 billion offer (that was not finalized) in the months leading up to the valuation date.

I also noted that while this synergy had been provided to the seller in the financial control valuation, all other potential synergies, including those from operating expenses or enhanced revenues or lower cost of capital, were specifically allocated to hypothetical buyers.

The Court did not allow this benefit, noting that I have written that

S corporations should not be worth more than C corporations. What I have long said is that S corporations should not be worth more than otherwise identical C corporations. The Court’s decisions regarding the tax rate above assured that AriZona was valued at less than an otherwise identical C corporation. The decision regarding the tax amortization benefit denied the value impact of a benefit that was clearly already on the table in negotiations ongoing only a few months before the valuation date.

The effect of not including the tax amortization benefit lowered the Court’s conclusion of fair value by about 14% (about $336 million) relative to the $2.364 billion conclusion of financial control value in the Mercer Report.

5. The Terminal Value Estimation

The final cash flow in the DCF method is the estimation of the terminal value, which represents the present value of then-remaining future cash flows at the end of the finite projection period.

The Court rejected the terminal value estimation in the Ruback Report, which called for a liquidation of the business at the end of the ten year forecast period. The Court believed that AriZona was a company poised for long-term growth.

The long-term growth rate assumption used in the terminal value estimation in the Mercer Report was 4.5%, which was the sum of long-term real growth and inflation, as discussed in the Mercer Report. The weighted average cost of capital was 10.8%, so the terminal multiple of net cash flow was [1 / (10.8% – 4.5%)], or an implied multiple of terminal year EBITDA of just under 9x.

The Court accepted the terminal value estimation from the Mercer Report, noting that it might be too conservative.

6. The Discount Rate (Weighted Average Cost of Capital)

There was little development of the discount rate in the Ruback Report, which concluded with a weighted average cost of capital (“WACC”) of 11.0%.

The WACC was developed in the Mercer Report using a “build-up method” to reach an equity discount rate. The equity discount rate included consideration for company-specific risk associated with the centrality of Mr. Vultaggio to the Company’s operations as well as risks associated with the sustainability of new product innovation.

The cost of debt was estimated and a capital structure was assumed based on the (non-comparable per the Court) guideline public companies in the Mercer Report.

The resulting WACC was 10.8% for the October 5, 2010 valuation date, which was accepted by the Court.

7. “Key Man” Discount

As noted above, the Mercer Report included consideration of Mr. Vultaggio’s importance to the Company in the development of the discount rate. Pratt testified on behalf of Vultaggio regarding a key man discount, but none was employed in the Ruback Report.

Given the testimony at trial about the importance of Vultaggio to the operations of AriZona, the Court believed that it was important for this to be considered in the valuation process. Pratt also testified that consideration for a key person discount could be included as an adjustment to the discount rate in a discounted cash flow method.

The Court considered that the Mercer Report had made appropriate consideration of key man issues in the discount rate development, which was accepted as noted above.

8. Outstanding Cash, Non-Operating Assets and Debt

The Court accepted the analysis of non-operating assets and the consideration of debt as presented in the Mercer Report. There was significant cash on hand at both valuation dates as well as other non-operating assets that were readily collectible. There was also some debt owed primarily to Vultaggio.

The Ruback Report subtracted debt at the valuation date, but did not include cash or other non-operating assets in its conclusion. Rather, those assets were held for the ten years of the forecast period and then discounted for ten years to the present in the Ruback Report, which argued that the cash was needed for operations. Given the 11.0% WACC in the report, this effectively discounted the non-operating assets by 65%, or about $100 million.

A specious argument was made in the Ruback Report that the cash was needed to pay for the valuation judgment. The Court saw clearly that the cash was a part of value at the valuation date and that payment of the valuation judgment was a separate issue.

The Court observed that the net non-operating assets were $137.6 million at October 5, 2011 and $161.4 million at January 31, 2011. Both totals were derived from the Mercer Report.

The Court’s Financial Control Value

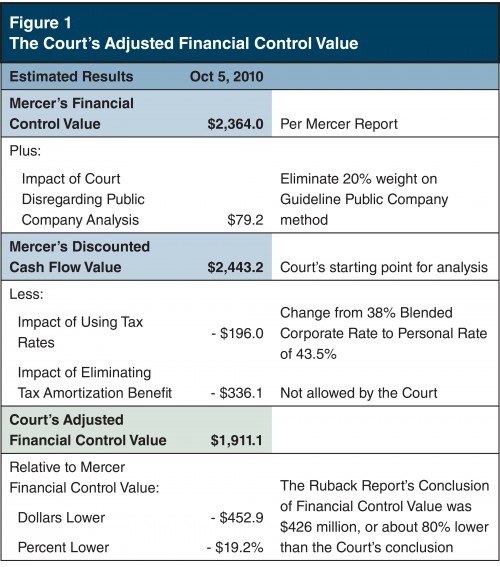

The Court did not provide a separate section to develop its financial control value, so we will do so now for clarity. Figure 1 summarizes the discussion to this point.

The economics of the Court’s analysis can now be summarized in relationship with the original DCF valuation in the Mercer Report. As the preceding discussion shows, the Court accepted the Mercer Report’s Financial Control conclusion with three exceptions:

- No weight was placed on the guideline public company method. This had the effect of increasing value by about 3%. So the beginning point of the Court’s analysis was $2.443 billion, as shown in Figure 1.

- The Court changed the blended federal/state tax rate of 38% in the Mercer Report to the personal rate of 43.5% from the Ruback Report. This had the effect of decreasing the Court’s conclusion by about 8%, or by $196 million.

- Finally, the Court did not allow the tax amortization benefit employed in the Mercer DCF analysis. This lowered the Court’s conclusion by $336 million, or about 14%.

Overall, my interpretation of the Court’s financial control value was $1.911 billion. Relative to the $2.364 billion conclusion of financial control value in the Mercer Report, the Court’s conclusion was lower by $453 million, or about 19%.

The Court’s financial control value of $1.991 billion is 4.7 times greater than the analogous conclusion in the Ruback Report of $426 million. I make the comparison at the financial control level because that’s the level at which such comparisons should be made in a fair value matter in New York. I say that because courts, and this Court, often show an ability to understand the economics of valuations. Justice Driscoll certainly did that.

But when it comes to the next assumption, the discount for lack of marketability, or DLOM, or marketability discount, the courts in New York make the rules. The only problem is that they don’t tell appraisers or anyone what the rules are.

9. The Marketability Discount (DLOM)

The Court’s treatment of the marketability discount does not make sense from my perspective as a business valuer and a businessman. The discussion of the marketability discount, which is a $478 million adjustment in the Court’s analysis, consists of just over three pages.

Because this marketability discount is such a large and important adjustment, I will spend a significant amount of space discussing it.

The Pratt and Ruback Reports

The Court’s determination of fair value was clearly conducted at the financial control level of value. The beginning point for the Court’s determination was the financial control values provided in the Mercer Report as of October 5, 2010. The methodology of the Ruback Report also yielded a conclusion at the financial control level of value.

The Ruback Report cited two studies in developing the DLOM, the Longstaff Model and the Silber Study.11 The Ruback Report stated that the Longstaff Model provided an “upper bound” for marketability discounts, and it was ignored in the final conclusion regarding the marketability discount.

The Silber study reported an average restricted stock discount of 34%, and this was used as the basis for the Ruback Report’s conclusion of a 35% marketability discount.

As pointed out in the Reply Report, this use of the average from the Silber Study was inappropriate and misleading.12

- The Silber Study broke its sample into two distinct populations, those with discounts greater than 35% and those with discounts less than 35%.

- The group with discounts greater than 35% had a mean discount of 54%, median prior year revenues of $13.9 million and median prior year loss of $1.4 million. This group had an average market capitalization of $34 million.

- The group with discounts less than 35% looked entirely different. The mean discount was a much lower 14%, average revenues were $65 million, with median prior year earnings of $3.2 million, and an average market capitalization of $75 million.

- Compared with the second group of the Silber Study, AriZona had revenues of approximately $1.0 billion and pro forma after-tax net income of approximately $100 million. Even using the Ruback Report’s flawed equity valuation of $426 million (before discounts), AriZona would be among the most attractive companies in the second group, if not the most attractive. If detailed transactional information were available from the Silber Study, relevant comparisons might suggest that a premium (i.e., a negative discount) should be applied. The range of “discounts” in the Silber Study was from a minus 13% (a premium of 13%) to a discount of 84%. Given AriZona’s attractiveness relative to the sample of companies studied, the Silber Study supports a marketability discount of zero percent.

Pratt also testified that the appropriate marketability discount should have been 35%. The Pratt Report cited numerous minority interest studies and analyzed a number of factors, most of which applied to illiquid minority interests of companies, although he also testified that any DLOM should be based only on corporate or enterprise factors and not on shareholder level factors.

Unfortunately, I did not get time during direct testimony to address Ruback’s 35% DLOM. Counsel for AriZona certainly did not want to question me about it during their cross-examination of me.

The Mercer Report

The Mercer Report cited a number of New York cases in support of a recommended marketability discount of 0%. I will discuss those in the context of the analysis of the Court’s treatment below.

The bottom line is that AriZona is a large, highly successful company in a niche in the beverage industry that many players, both in the beverage industry and outside it, would like to own. Graphically, this positioning was shown in the Mercer Report as follows:

AriZona (and Ferolito) had had significant discussions with Coca-Cola, Nestle Waters, and Tata Tea in the months and years prior to the valuation date. These discussions yielded informal offers ranging from $2.9 billion to more than $4 billion for 100% of the AriZona Entities.

The record was clear that Vultaggio did not want to sell his shares or the Company in total. He exhibited reluctance to complete any transaction leading to the valuation dates and did not cooperate to facilitate the sale of the Ferolito shares. Ultimately, there were no transactions leading to the valuation date.

The Mercer Report referred to discussions like those noted above as indicative of the interest of capable buyers. This was one factor considered in concluding that the appropriate marketability discount was 0%.

The Court’s Analysis

The Court began its analysis by stating:13

At the outset, nearly all courts in New York that have considered the question of whether to apply a DLOM have answered in the affirmative.

I knew trouble was coming when I read that sentence. The Court then went on:14

The instant case is readily distinguishable from each of the three cases upon which Ferolito relies in support of his claim that there should not be any DLOM at all. [emphasis added]

I’m not a lawyer, but it seems to beg the question to begin an analysis by saying that nearly all courts have said positive marketability discounts were appropriate as a basis for applying one in the case of AriZona. Every case is fact-dependent. The fact is, there are a growing number of New York fair value decisions where 0% or very small marketability discounts have been concluded. This should make it important to reference at least some of them to see how AriZona compares.

I testified in Giaimo, which involved two real estate holding companies. In that case, a special master concluded that the appropriate marketability discount was 0%.15 The 0% discount was affirmed by the New York Supreme Court, although using only a portion of the logic that I testified about. On appeal, the marketability discount was concluded to be 16%.16

I also testified in the case Man Choi Chiu and 42-52 Northern Boulevard, LLC v. Winston Chiu, involving another real estate holding company.17 In that case, the New York Supreme Court held that a 0% marketability discount was appropriate. That decision was left untouched in the appeal of the matter.

As we will see, there are other 0% marketability discount cases, some of which are more relevant to AriZona than real estate holding companies.

The Court said that Ferolito (Mercer) relied on three cases in support of no marketability discount. There were actually six cases analyzed in the Mercer Report from business and valuation perspectives.

Friedman v. Beway18

Beway was cited in the Mercer Report in support of the selection of the control level of value. Beway was cited in the early “General Principles of Valuation” section of the Court’s decision, but it was not cited in the Court’s short discussion of the marketability discount.

However, Beway itself is instructive regarding the applicability of a marketability discount, at least from a logical standpoint. Key citations were included in the discussion. Beway is quoted in the Mercer Report to illustrate important guidance in fair value determinations:

“[I]n fixing fair value, courts should determine the minority shareholder’s proportionate interest in the going concern value of the corporation as a whole, that is, ‘what a willing purchaser, in an arm’s length transaction, would offer for the corporation as an operating business.'”

This is the same quotation found at the beginning of this analysis regarding the appropriate level of value. Beway addresses the applicability of a minority discount:

“[a] minority discount would necessarily deprive minority shareholders of their proportionate interest in a going concern,”

This is important because such a discount:

“would result in minority shares being valued below that of majority shares, thus violating our mandate of equal treatment of all shares of the same class in minority stockholder buyouts.”

Beway also argues against the unjust enrichment that would occur if a minority discount were allowed in a New York fair value determination.

“to fail to accord to a minority shareholder the full proportionate value of his [or her] shares imposes a penalty for lack of control, and unfairly enriches the majority stockholders who may reap a windfall from the appraisal process by cashing out a dissenting shareholder.”

Again, I’m not a lawyer, but the economic effect of applying a marketability discount is to lower the price below that which “a willing purchaser, in an arm’s length transaction, would offer” for a business as a going concern.

Further, the application of marketability discount results in “minority shares being valued below that of majority shares” and therefore violates the principle that “all shares of the same class” be treated equally.

Finally regarding these quotes, the application of a marketability discount provides a windfall to control shareholders by imposing “a penalty for lack of control,” because no controlling shareholder would ever sell his or her shares based on a discount for lack of marketability. We will see the effect of this penalty below.

Beway, unfortunately, is inconsistent on its face in arguing strongly against the application of a minority discount while calling for consideration of a marketability discount, which, if applied, undermines the very principles that the case espouses. Obviously, that is my opinion from business and valuation perspectives. I have no legal opinions.

Matter of Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches, Inc.19

The Court attempted to distinguish Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches, which provided for a 0% marketability discount, from AriZona. In Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches, “a DLOM was not appropriate where there was testimony of increased profits, expansion and 120 responses to a ‘for sale’ advertisement in the Wall Street Journal.”

First, there was adequate testimony of “increased profits and expansion” for AriZona leading to the valuation dates (covered above). The Court seemed to think that because there were a “geometrically smaller number of expressions of interest for AriZona”, this is not a valid comparison from a business perspective. However, companies like AriZona are not sold through advertisements in the Wall Street Journal or anywhere. Large companies are carefully marketed by qualified professionals to limited universes of carefully selected financial and strategic buyers. There was substantial testimony from investment bankers regarding the attractiveness and marketability of AriZona.

The Mercer Report stated about Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches specifically, following significant discussion regarding the attractiveness and marketability of AriZona:20

In Matter of Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches, the Court rejected application of a marketability discount, finding that: “The record, including testimony of increased profits, expansion and 120 responses to a ‘for sale’ advertisement in The Wall Street Journal, amply supports a finding of respondent’s marketability.” If offered for sale, multiple potential acquirers would be interested in acquiring the AriZona Entities.

The AriZona Court’s analysis of Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches, in my opinion from a business perspective, fails to demonstrate that the relevant facts are “readily distinguishable” from AriZona.

Ruggiero v. Ruggiero21

The AriZona Court noted that in Ruggiero, “there was ‘insufficient explanation’ to support a DLOM, which is far from the case here.” That’s the entire distinction made. If we look at the decision in Ruggiero, we see something different:22

The sole issue the Court had with Mr. Glazer’s explanation was his 20% discount for lack of marketability for which he did not provide sufficient explanation. In this sense the Court agreed with Plaintiff’s expert that Zan’s does constitute a somewhat unique niche business. Thus, the Court removed…the deduction for lack of marketability.

One expert did not provide sufficient explanation for a 20% marketability discount. The other described the company as a “somewhat unique niche business,” and apparently suggested a 0% marketability discount. The Ruggiero Court agreed with that characterization, and removed the marketability discount.

The AriZona Court also noted that Ruggiero was not a BCL § 1118 case. This would appear to be a distinction without a difference because Beway instructs that the same valuation principles hold for BCL § 623 cases.

In the Mercer Report, it was noted:23

In Ruggiero v. Ruggiero, the Court concluded that no marketability discount was appropriate since the subject business constituted “a somewhat unique niche business.” Among the unique attributes of the AriZona Entities is the fact that it is one of only four (and the only private) available U.S. non-alcoholic beverage systems with scale available to potential acquirers.

The AriZona Court’s analysis of Ruggiero, in my opinion from a business perspective, fails to demonstrate that the relevant facts are “readily distinguishable” from AriZona.

O’Brien v. Academe Paving, Inc.24

The AriZona Court’s entire dismissal of O’Brien v. Academe Paving is in a single sentence: “Finally, in O’Brien v. Academe Paving, Inc. (citations omitted) the trial court appears to have applied an impermissible minority discount, rather than a DLOM.” 25

The O’Brien Court did refuse to allow an impermissible minority discount, citing the same passage from Beway noted above. Unfortunately, the characterization of the discussion regarding the DLOM would appear to be incorrect.

The Court in O’Brien quoted Beway about the appropriateness of consideration of marketability discounts and then noted:

The Court continued, in that same decision [Beway], and repeats here, that marketability discounts for close corporations (such as these here) are entirely proper if it is a factor used in valuing the corporation as a whole, not just a minority interest. 26

At several points, the O’Brien Court stated that Academe/JOB was a very desirable and marketable commodity within the paving industry. The purpose of valuations conducted near the valuation date was to assist with a potential sale of the business. The business was marketable, attractive and was for sale.

The O’Brien Court concluded regarding the marketability discount:

As Mr. Griswold saw no need to factor an illiquidity discount into his analysis of the “enterprise value” of Academe/JOB for either April or November of 1999, so the Court sees no need to do so now.

It should be clear that the application of a 0% marketability discount in O’Brien v. Academe Paving was an intentional decision by that Court based on the facts and circumstances of the case.

The analysis in the Mercer Report stated the following about O’Brien:

In O’Brien v. Academe Paving, Inc. the Court noted that marketability discounts are appropriate in fair value determinations in cases for which “the reduction of value of close corporations is thought to be necessary to reflect the (theoretical) circumstance that no ‘market’ buyer would want to buy into such a corporation, even if shareholders were willing to sell their interests (which, under most circumstances, they are not).” Noting that, in a sale of the subject business, petitioners’ shares would not be subject to discount, the Court concluded that, since the subject company was “a very desirable/marketable commodity” within its industry, the appropriate marketability discount was 0%. The attractiveness and desirability of the AriZona Entities to potential acquirers has been discussed throughout this report.27

The AriZona Court’s analysis of O’Brien v. Academe Paving, in my opinion from a business perspective, fails to demonstrate that the relevant facts are “readily distinguishable” from AriZona.

The Mercer Report discussed two other cases.

In Quill v. Cathedral Corp., the Court noted that the receipt of offers for the subject business (and a subsequent sale at the asking price within a reasonable period of time) indicated that “the actual sales price received reflected any marketability discount and that no further deduction should be made from the value of petitioners’ shares.”28 The Supreme Court’s reasoning was upheld on appeal.29 We should note that there was a second, apparently less marketable company involved in this litigation. For that company, the Supreme Court applied a 15% marketability discount, which was also upheld on appeal. With respect to the AriZona Entities, the conclusion of fair value is consistent with the offers from potential acquirers discussed previously in this report.30

and,

In Adelstein v. Finest Food Distributing Co.,31 the Court determined that a 5% marketability discount was appropriate for the subject business by reference to assumed transaction costs involved in a sale. As a percentage of the sales price, transaction costs are generally inversely related to the amount of the proceeds. In the event of the sale of a multi-billion company like AriZona, one would anticipate transaction costs to be much less than 5% of the purchase price.32

Another case was mentioned by the AriZona Court, that of Zelouf International Corp. v. Zelouf, which was published shortly before the decision in AriZona.33 In that case, Justice Kornreich did not apply a marketability discount. The AriZona Court noted that “as readily demonstrated by the stalled Nestle negotiations, the very reasons for a DLOM here have resulted in – or are at least strongly correlated with – the failure of Ferolito to sell his shares prior to the proceeding.”

Zelouf actually stands for another principle (as I read it from business and valuation perspectives), that the lack of desire on the part of controlling shareholders to sell, potentially ever, should not be the cause for imposing an illiquidity discount on the dissenters (or, by inference, on Ferolito in the AriZona matter). Peter Mahler, writer of the well-known New York Business Divorce Blog, wrote the following:

Justice Kornreich found the risk of illiquidity associated with the company “more theoretical than real,” explaining there was little or no likelihood the controlling shareholders would sell the company, i.e, themselves would incur illiquidity risk upon sale. Imposing DLOM in valuing the dissenting shareholder’s stake, therefore, would be tantamount to levying a prohibited discount for lack of control a/k/a minority discount.34

The AriZona Court distinguished this matter from Zelouf based on stalled Nestle negotiations involving Ferolito. In Zelouf, Justice Kornreich accepted a 0% marketability discount because the controlling shareholders did not want to sell, potentially ever. The logic was that if the controlling shareholders would never suffer from illiquidity, then the dissenting shareholder should not be charged with a marketability discount. Vultaggio did not want to sell at all and was very clear about that in both word and actions.

A further development in Zelouf was published December 22, 2014.35 In this supplemental decision, Justice Kornreich made the following statements:

[N]o New York appellate court has ever held that a DLOM must be applied to a fair value appraisal of a closely held company. On the contrary, the Court of Appeals has held that “there is no single formula for mechanical application.” Matter of Seagroatt Floral Co., Inc., 78 NY2d 439, 445 (1991). Indeed, the Court of Appeals recognizes that “[v]aluing a closely held corporation is not an exact science” because such corporations “by their nature contradict the concept of a market’ value.” Id. at 446. As set forth in the Decision, since Danny is not likely to give up control of the Company, Nahal should not recover less due to possible illiquidity costs in the event of a sale that is not likely to occur. [emphasis added]

And further:

[I]n this case, under the unique set of facts set forth in the Decision, applying a DLOM is unfair. This court’s understanding of the applicable precedent is that, while many corporate valuation principles ought to guide this court’s analysis, this court’s role is not to blithely apply formalistic and buzzwordy principles so the resulting valuation is cloaked with an air of financial professionalism. To be sure, sound valuation principles ought to be and indeed were utilized in computing the Company’s value (i.e., the court’s adoption of most of Vannucci’s valuation). Nonetheless, the gravamen of the court’s valuation is fairness, a notion that is undefined, making it a classic question of fact for the court. Fairness, in this court’s view, necessarily requires contextualizing the applicable valuation principles to the actual company being valued, as opposed to merely deciding a priori, and in a vacuum, that certain adjustments must be part of the court’s calculus. From this perspective, the court reached its conclusion that an application of a DLOM here would be tantamount to the imposition of a minority discount. Consequently, the court finds it fairer to avoid applying a minority discount at all costs rather than ensuring that all hypothetical liquidity risks are accounted for. [Citation omitted.] [emphasis added]

Justice Kornreich went on to say that if forced to impose a marketability discount, it would be 10%, citing another recent New York fair value case, Cortes v. 3A N. Park Ave Rest Corp.36 Suffice it to say, Zelouf is not “readily distinguishable” from the AriZona matter, at least in my opinion from business and valuation perspectives. Rather, the logic of Zelouf supports a 0% marketability discount, since it was the actions of the controlling shareholder, Vultaggio, that caused Ferolito’s sale negotiations to break down.

The AriZona Court went on to agree with Vultaggio that their claims justified “some semblance of a discount.” Those bases included the following:

- the fact that AriZona did not have audited financial statements for many years prior to the valuation date

- the extensive litigation between the shareholders,

- the uncertainty about the company’s S Corporation status,

- the transfer restrictions in the Owner’s Agreement.

These issues do not, in my opinion, justify a marketability discount of 25% for AriZona, as will be seen through the Court’s own analysis.

- Testimony showed that absent shareholder fighting, AriZona’s financial statements could readily be audited. The reasons for the lack of a completed audit stemmed from the litigation at hand. The Court stated:

“First, as Gelling’s testimony established, AriZona’s financial statements can be readily audited, particularly when the shareholders are no longer battling with each other.” (emphasis added)

- Importantly, the litigation between the two shareholders would be terminated by the very case at hand. The Court stated:

“Second, as credibly explained by Ferolito’s investment banker Rita Keskinyan, the litigation between the two shareholders would necessarily cease when one shareholder’s interests are acquired.” (emphasis added)

And the litigation would surely cease if 100% of the Company were sold as a “going concern” in the hypothetical transaction contemplated by Beway.

- The so-called “uncertainty about the company’s S-Corporations status” was likely immaterial. The Court stated:

“Third, the uncertainty about the company’s S-Corporation status is, at most, a scenario about which reasonable minds have differed.” (emphasis added)

Further, no buyer of AriZona would be concerned about the S corporation status. The buyer would only purchase assets if there were any concern at all. Any remaining issues re S corporation status would be a problem for the remaining owners of shell S Corporation (i.e., after assets are sold), and not a problem for the purchaser, who bought assets.

- Transfer restrictions on interests in a company’s equity in an Owner’s Agreement should logically have no impact on the value of 100% of the equity of a business sold as a going concern, which is the standard from Beway, which states that such restrictions should be “literally inapplicable.”

The AriZona Court undermined its own logic for a substantial marketability discount in its own analysis, at least as I read the decision from business and valuation perspectives.

I think that this discussion shows that a 25% DLOM for an attractive, saleable company like AriZona, is excessive and unreasonable, or, to use Justice Kornreich’s term, perhaps unfair.

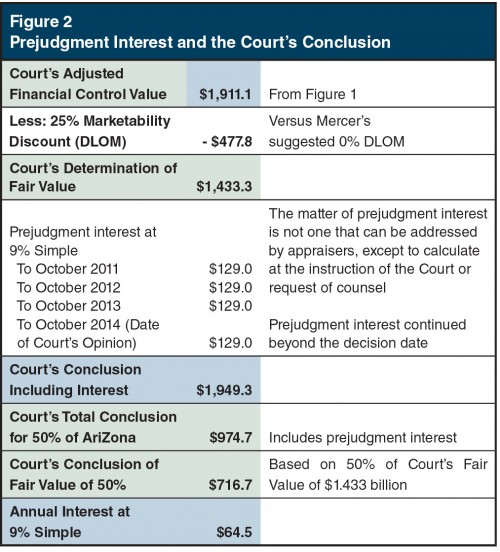

DLOM and Prejudgment Interest

The combined impact of the three changes to assumptions in the Mercer Report’s financial control analysis lowered the Court’s adjusted financial control value to $1.911 billion (from $2.364 billion), which was derived in Figure 1 above. Figure 2 picks up at that point.

The Court imposed a 25% marketability discount. What does that mean? Well, it lowered value by some $478 million. That is a tremendous price for so-called lack of marketability or illiquidity, particularly given the obvious and demonstrable desire of capable buyers to acquire AriZona. I seldom use words like that in writing, but it is unavoidable. The conclusion of financial control value was lowered from $1.911 billion to $1.433 billion, which was the Court’s conclusion of fair value in AriZona.

For context, a marketability discount of 5% was allowed in the Adelstein v. Finest Food Distributing Co. based on assumed transaction costs on a sale of the business. As noted above and in the Mercer Report, with a company the size of AriZona, such transaction costs would be substantially lower than 5%. A 5% marketability discount would provide for almost $100 million of transaction costs in an actual sale of Arizona at the Court’s financial control value of $1.911 billion. That would, in my opinion, be quite excessive in itself.

At this point, we see that the Court found that prejudgment interest was due Ferolito because of the wait between the October 2010 valuation date and the October 2014 decision date. The prejudgment interest, which was set at 9%, continued based on the decision until the matter was resolved.

Prejudgment interest at a simple interest rate of 9% per year amounts to $129 million on a base fair value of $1.433 billion. In the four years between the valuation and decision dates, the accrual of interest raised the Court’s conclusion to $1.949 billion, as estimated in Figure 2.

The value of the combined Ferolito 50% interest in AriZona based on the conclusion of fair value plus prejudgment interest was therefore $975 billion, which was to accrue prejudgment interest at the rate of 9% (simple), or $64.5 million per year (or half of $129 million on 100% of the concluded fair value). These are big numbers, but AriZona is a big and valuable private company.

An Impermissible Minority Discount?

The Court performed its analysis and developed a conclusion of fair value at the financial control level of value of $1.911 billion. It then took a 25% marketability discount. We examined prejudgment interest in Figure 2. However, prejudgment interest is not part of value. It is interest, or payment for waiting from October 2010 (valuation date) to October 2014 (decision date) to receive the judicial determination of fair value.

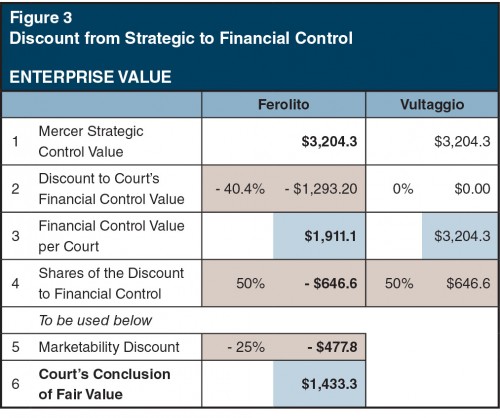

We return to examining only the conclusion of fair value before the imposition of prejudgment interest in Figure 3.

Assume with me that the conclusion of strategic value in the Mercer Report of $3.204 billion is reasonable. In a real transaction, corporate tax rates would be used by real market participants and the tax amortization benefit would be considered in the negotiations leading to a transaction.

I am not arguing with the Court about the decision to disregard strategic control value in favor of financial control value, but it is important to see the impact of decisions and examine them in that light. As seen above, there is a $1.293 billion discount from the strategic control value to the Court’s financial control value. In the absence of litigation, Ferolito and Vultaggio each owns half of the option value of selling the company and receiving their respective shares of strategic control value.

The decision to move to financial control reduces the Ferolito share by $647 million, which is a direct addition to the Vultaggio option value. We will use this result below.

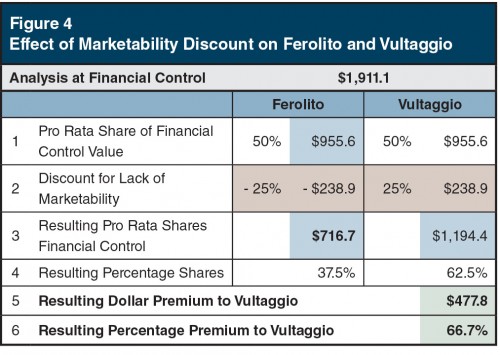

The Court imposed a 25% marketability discount to its concluded financial control value of $1.911 billion, yielding a resulting conclusion of fair value of $1.433 billion. However, the focus of the analysis is on the marketability discount of 25%, or $478 million dollars. Figure 4 focuses only on financial control value.

Figure 4 begins with the Court’s concluded financial control value of $1.911 billion.

Remember, value is value and interest is interest, so to understand the value transfers involved in the Court’s analysis, we have to focus on financial control value.

Ferolito and Vultaggio share in financial control value at 50% each. Their pro rata shares are therefore $956 million each, or half of $1.911 billion each. The Court imposed a 25% marketability discount, so the Ferolito share is reduced by $239 million, yielding an indication of fair value of $717 million, or 50% of the Court’s after DLOM value conclusion of $1.433 billion (Figure 3).

The results get interesting here. While Ferolito’s value is reduced by the marketability discount, Vultaggio’s value is increased by exactly the same amount. Vultaggio’s share of the Court’s financial control value is $1.194 billion, or 62.5% of financial control value of $1.911 billion. Vultaggio’s $717 million share represents only 37.5% of that value.

The result of the imposition of a 25% marketability discount is to transfer $478 million of value to the Vultaggio column, resulting in a 66.7% premium in value for Vultaggio. In other words, the imposition of the marketability discount at the enterprise level ($478 million) resulted in a shift in value of that entire amount to Vultaggio’s 50% interest.

The imposition of a marketability discount of 25% results in a dollar-for-dollar penalty in value for the seller in a fair value case where the ownership is 50%-50%. What this boils down to deserves highlighting:

Mathematically and practically, the imposition of a minority discount would do exactly the same thing as the imposition of a marketability discount. However, transferring value by imposing a minority interest discount is forbidden by Beway. If transferring value from the minority (or non-controlling) owners to the controlling owners is forbidden on the one hand (i.e., a minority discount), it would seem that the other hand (i.e., the marketability discount) would be forbidden as well. From the viewpoint of the non-controlling shareholder, there is no distinction – value transferred to the controlling owner(s) is value transferred by whatever name it is given.

I’m reminded of the father who told his son not to hit his sister after he was caught in the act. He stopped, but a few minutes later, he kicked her. When his father asked why he had done that, he said because you didn’t tell me not to kick her. Well, the New York courts say emphatically that you can’t hit your sister (i.e., by imposing a minority discount). But then the father (New York appellate courts) say you can kick her (by imposing a marketability discount). No wonder the kids (judges, lawyers, and business appraisers) are confused.

This is an issue that desperately needs clear appellate court guidance in New York.

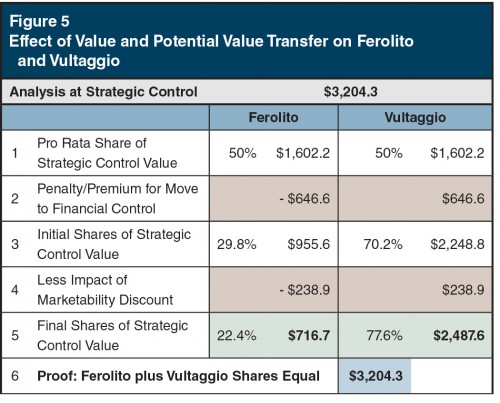

In Figure 5, we see that there is countervailing logic against the marketability discount, because given that the Court in the AriZona matter selected the financial control level of value rather than the strategic level, potential value is definitely transferred to Vultaggio in this case and controlling owners in general when marketability discounts are applied.

Figure 5 examines both the potential shift in value in moving from strategic to financial control as well as the actual shift in value by imposing a 25% marketability discount in the AriZona matter.

In Figure 5, we again begin with the strategic control value from the Mercer Report of $3.204 billion.

Line 1. Ferolito and Vultaggio each share, while they are 50%-50% owners, this potential value (or option), or $1.602 billion each in value. We calculated the discount in potential value from the strategic level down to Court’s financial control to be $1.293 billion (i.e., from $3.204 billion down to $1.911 billion) in Figure 3.

Line 2. This results in a loss of potential value of $647 million (half of the discount from Strategic Control to Financial Control) for Ferolito, which is accretive to value to Vultaggio by exactly the same amount. What that means is that, at least theoretically, the day after the settlement, Vultaggio could sell the Company for $3.204 billion and reap a substantial windfall. That potential windfall is the $647 million discount for Ferolito that is added to the Vultaggio column.

Line 3. The financial control value for Ferolito is $956 million. In practical terms, Vultaggio would receive $3.204 billion in the hypothetical sale and then pay Ferolito at the $956 million financial control value (or repay the lender), leaving him with $2.249 billion. This amount is 2.4 times greater than the financial control value accorded to Ferolito.

Line 4. At this point, we apply the Court’s 25% marketability discount in the Ferolito column. The way things work, this is a direct shift of an equivalent amount to Vultaggio.

Line 5. The concluded fair value for the 50% Ferolito share of AriZona is $717 million. This compares to the concluded potential value for Vultaggio of $2.488 billion, or 3.5 times greater.

I am not arguing for the use of strategic control value in New York fair value cases. That is a matter for New York appellate courts to decide. However, I am suggesting that for the potential benefit of strategic value that applies in operating business cases for remaining owners, equity (dare I use that word) could call for the elimination of the marketability discount in New York fair value cases.

Without providing detailed evidence at this point, I can safely say that the great majority of jurisdictions in the United States have reached this conclusion.

Concluding Thoughts

This has been a lengthy analysis. Let’s conclude with a few highlights:

- In my opinion, at least, the logic supporting a marketability discount of 0% for attractive, marketable companies, and relevant comparisons to AriZona, should have supported the 0% conclusion for the marketability discount in the Mercer Report in New York fair value cases.

- The case law logic supporting a minority discount of 0% in selected New York cases would also, if applied consistently, support a 0% marketability discount for an attractive, saleable company like AriZona.

- In this matter, any valuation discount, whether a minority discount or a marketability discount, has the effect of transferring value directly from the non-controlling owner(s) to the controlling owner(s).

- As shown in this analysis, the selection of financial control as the appropriate level of value for an operating company like AriZona already provides a potential “windfall” for controlling shareholders. I’m not suggesting that any court should order a sale of a company to achieve this value or select strategic value as the appropriate level of value for fair value. However, I do suggest that it is an equitable issue that could or should be considered in fair value determinations in New York.

- Lastly for this summary, prejudgment interest is not value as of a valuation date. We cannot reasonably look at the Court’s conclusion, including interest, as the conclusion of fair value. That conclusion represents fair value plus prejudgment interest, and interest is interest, not value. The enormous transfer of value and potential value that occurred with this decision is masked by thinking that the final conclusion, including interest, represents fair value. Fair value was – and had to be – determined at the valuation date of October 5, 2010.

In the final analysis, the Court substantially agreed with the DCF method as employed in the Mercer Report, differing only on three assumptions. The Court then applied a marketability discount of 25%, which, in my opinion and based on the analysis above, was not differentiated to AriZona and was not justified. In fact, it was undermined by the Court’s own analysis.

The good news is that the matter has been settled between the parties. A long and contentious period of litigation has ended. The settlement has not been made public, and that likely will not occur.

The bad news is that the Court of Appeals in New York will miss an excellent opportunity to reexamine the marketability discount issue.

ENDNOTES

- John M. Ferolito and JMF Investments Holdings, Inc., Plaintiffs, against AriZona Beverages USA LLC, AZ National Distributors LLC, AriZona Beverage Company LLC, Defendants, In the Matter of the Application of John M. Ferolito, the Holder of More Than 20 Percent of All Outstanding Shares of Beverage Marketing, USA, Inc., Petitioner, For the Dissolution of Beverage Marketing, USA, Inc., John M. Ferolito and the John Ferolito, Jr. Grantor Trust (John M. Ferolito and Carolyn Ferolito as Co-Trustees), both individually and derivatively on behalf of Beverage Marketing USA, Inc., Plaintiffs, against Domenick J. Vultaggio and David Menashi, Defendants. New York Supreme Court, Nassau County, No. 004058-12. (“Ferolito v. Vultaggio”)

- Others have written about the AriZona Matter, including:

Peter Mahler, New York Corporate Divorce Blog, “Court Rejects Potential Acquirers’ Expressions of Interest, Relies Solely on DCF Method to Determine Fair Value of 50% Interest in AriZona Iced Tea,” October 27, 2014

Gilbert E Matthews (Parts I and II) and Michelle Patterson (Part II):, Financial Valuation and Litigation Expert, “How the Court Undervalued the Plaintiffs’ Equity in Ferolito v. AriZona Beverages:”

“Part I: Tax-Affecting S Corporation Earnings” (April/May 2015)

“Part II: Ferolito and the Application of DLOM in New York Fair Value Cases” (June/July 2015).

- Friedman v. Beway Realty Corp., 87 N.Y.2d 161, 168 (1995) (emphasis in original) (quoting Matter of Pace Photographers, Ltd., 71 N.Y.2d 737, 748 (1988)).

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- Expert Report of Richard S. Ruback, dated February 17, 2014, with valuation conclusions as of December 31, 2010 (“the Ruback Report”), page 4.

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- The forecasted growth in the Mercer Report for financial control was actually at a CAGR of 7.7%. The Court’s reference to a 10.2% CAGR actually applied to Mercer’s strategic control value, which considered the ability of a strategic partner to enhance growth. Both forecasts were provided in the Bellas Report previously mentioned.

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- Pratt, Shannon P., Valuing a Business Fifth Edition (McGraw Hill, 2008), pp. 618-619.

- Francis A. Longstaff. “How Much Can Marketability Affect Security Values?” The Journal of Finance, December 1995, Vol. 50, No. 5, pages 1767-1774, and William L. Silber. “Discounts on Restricted Stock: The Impact of Illiquidity on Stock Prices.” Financial Analysts Journal, July August 1991, pages 60-64.

- Citing an analysis prepared by Mercer in a book published in 1997. Mercer, Z. Christopher, Quantifying Marketability Discounts (Peabody Publishing, 1994), pages 63-66.

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- Matter of Giaimo v. Vitale, 2011 NY Slip Op 50714(U) (Sup. Ct. NY County).

- Matter of Giaimo v. Vitale, 2012 NY Slip Op 08778 [101AD3d 523].

- Man Choi Chiu and 42-52 Northern Boulevard, LLC v Winston Chiu Index Nos. 21905/07, 25275/07.

- Beway v. Friedman.

- Matter of Walt’s Submarine Sandwiches, 173 A.D.2d 980, 981 (3d Dep’t 1991).

- The Mercer Report, Master Page 105.

- Ruggiero v. Ruggiero, Index No. 36299-2012 (2013).

- The Mercer Report, Master Page 104.

- The Mercer Report, Master Page 104.

- O’Brien v. Academe Paving, Inc., Index No. 99-2594 RJI No. 99-1794-M, at 13-14 (Sup. Ct. Broom Cnty. 2000).

- Ferolito v. Vultaggio.

- O’Brien v. Academe Paving, Inc., Index No. 99-2594 RJI No. 99-1794-M, at 13-14 (Sup. Ct. Broom Cnty. 2000).

- The Mercer Report, Master Page 104.

- Quill v. Cathedral Corp., RJI 10-90-2887, at 8 (Sup. Ct. Columbia Cnty, June 8, 1993).

- Quill v. Cathedral Corp. 215 A.D.2d 960 (3d Dep’t 1995).

- The Mercer Report, Master Page 104.

- Adelstein v. Finest Food Distributing Co., 2011 WL 6738941 (N.Y.Sup.), 2011 N.Y. Slip Op. 33256(U) (Sup. Ct. Queens Cnty. Nov. 3, 2011).

- Mercer Report, Master Page 105.

- Zelouf International Corp. v Zelouf, 2014 NY Slip Op 51462(U) [Sup Ct, NY County Oct. 6, 2014].

- Peter Mahler, New York Business Divorce Blog, “Court’s Rejection of Marketability Discount in Zelouf Case Guided by Fairness, Not ‘Formalistic and Buzzwordy Principles’,” January 5, 2015.

- Zelouf International Corp. v. Zelouf, Index 653652/2013 (Dec. 22, 2014).

- Cortes v 3A N. Park Ave Rest Corp., 2014 WL 5486477 (Sup Ct, Kings County Oct. 29, 2014).

About the Author

PDF ⬇ Download New York’s Largest Corporate Dissolution Case: AriZona Iced Tea