Now Is a Great Time to Transfer Stock to Heirs

Depressed Market Values Provide an Opportunity for Tax-Efficient Transfers of Family Wealth for Estate Planning Purposes

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are dire, and family businesses are not immune to the economic fallout from the virus. Yet we are confident that family businesses are best positioned to survive and lead in the post-pandemic economic recovery.

For family shareholders who are optimistic about the resilience of their family businesses and focused on the long view, this is an ideal time to execute intrafamily transfers in pursuit of estate planning objectives.

Coronavirus and Fair Market Value

The precipitous decline in public equity markets has been well documented. From its Feb. 19 peak, the S&P 500 index lost nearly 24% of its value by the end of the first quarter. Small-cap stocks in the S&P 600 index suffered even more, falling approximately 33% over the same period.

What caused the significant drop in public stock prices? Stock prices reflect three factors.

- Cash Flow. Stock prices are based on the future, not the past. Historical earnings and cash flows can provide important perspective, but investors are much more focused on what’s visible through the windshield than what is in the rearview mirror. For most public companies, the pandemic has caused investors to reassess the amount of cash flow those companies will generate in the coming year. Lower expected cash flows result in lower stock prices.

- Risk. When fog or other conditions reduce visibility, smart drivers slow down. Investors do the same thing. The pandemic has caused the range of potential cash flow outcomes for the coming year to be much wider than normal. In other words, stock investors are facing more risk than normal. When risk goes up, stock prices come down.

- Growth. The growth component describes how fast cash flows are forecast to increase in subsequent years. Theories abound as to whether the economic recovery curve from the pandemic will look a “V” or a “U” or a “W” (or some other letter). To the extent investors expect the negative effect of the pandemic to weigh on cash flows for a prolonged period, stock prices will be cut.

It is impossible to dissect the observed change in stock prices to discern how much of the decrease is attributable to expected cash flow, risk, or growth. What matters is that the three factors, in combination, have caused the reduction in public stock prices.

What does all this have to do with the fair market value of illiquid minority interests in private companies? The value of such interests depends on the same three factors.

Business appraisers determine the fair market value of shares for gifting or other intrafamily transfers using a two-step process.

- First, appraisers estimate the value of the business as if the shares were publicly traded. In other words, they consider how public market investors would view the shares if they had the opportunity to purchase them on the stock market. In doing so, they develop expectations regarding the cash flow, risks, and growth prospects of the family business. If a particular family business is better positioned to weather the COVID-19 storm than its peers, the negative impact on value may be muted. For many family businesses, however, an assessment of these three factors in the midst of the pandemic will likely result in a materially lower value than would have been the case in mid-February.

- Next, appraisers consider the appropriate discount, or reduction in value, to account for the fact that the shares in the family business are not publicly traded. All else equal, investors prefer to have liquidity. In order to accept the illiquidity inherent in private company shares, investors require a marketability discount. The size of the marketability discount depends on the specific attributes of the shares, including the likely holding period until a favorable opportunity for liquidity is expected, the amount of expected interim distributions from owning the shares, the expected capital appreciation over the holding period, and the incremental risk associated with illiquidity. The impact of the pandemic on the magnitude of the marketability discount is more ambiguous than the effect on the as-if-freely-traded value. Some of the factors are likely to be neutral relative to the pre-pandemic environment, while others may be negatively or positively affected.

In short, the fair market value of minority shares in family businesses is likely lower today than it was just a couple months ago. It does not matter if your family has no intention of selling the family business at a reduced value; the fact is that – if you were to sell an illiquid minority interest now – the value would reflect current market conditions. The IRS itself makes this clear in Revenue Ruling 59-60:

The fair market value of specific shares of stock will vary as general economic conditions change from ‘normal’ to ‘boom’ to ‘depression,’ that is, according to the degree of optimism or pessimism with which the investing public regards the future at the required date of appraisal. Uncertainty as to the stability or continuity of the future income from a property decreases its value by increasing the risk of loss of earnings and value in the future.

The potential silver lining to the cloud of depressed market values is that it provides an opportunity for more tax-efficient transfers of family wealth for estate planning purposes.

Case Study: Decisive vs. Hesitant Planning

We can illustrate the significance of the current opportunity with an example. Consider a family business having a pre-pandemic value on an as-if-freely-traded basis of $25 million. Although the long-term prospects of the business remain unchanged, the dislocations caused by coronavirus have triggered a temporary reduction in fair market value of 25%. The founder has yet to do any estate planning and continues to own 100% of the shares.

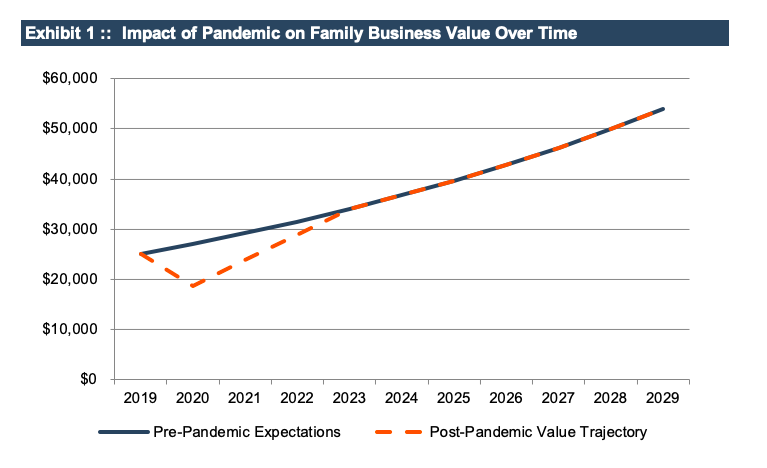

Exhibit 1 depicts the expected value trajectory for the family business both before and after the pandemic.

Because of the resilience of the family business, the value trajectory resumes its pre-pandemic path after three years. The founder’s tax advisers suggest that – since the long-term prospects of the business are unimpaired – the current depressed fair market value provides an excellent opportunity to begin a program of regular gifts. The current lifetime gift tax exclusion is approximately $12 million, and the founder and his advisers devise a strategy of making an initial gift of $6 million, followed by annual gifts of $1 million in each of the following six years.

We’ll examine two scenarios. In the first, the founder begins the gifting program immediately (the “Decisive” scenario). In the second, the founder defers the gifting program until the uncertainty associated with the pandemic has passed (the “Hesitant” scenario). In both cases, the shares gifted represent illiquid minority interests, so a 25% marketability discount is applied to derive fair market value.

Since the annual gifts are for fixed dollar amounts, lower per-share values result in more shares being transferred, which reduces the amount of shares in the future taxable estate, all else equal. Exhibit 2 summarizes the shares that are transferred under the gifting program for the Decisive and Hesitant scenarios.

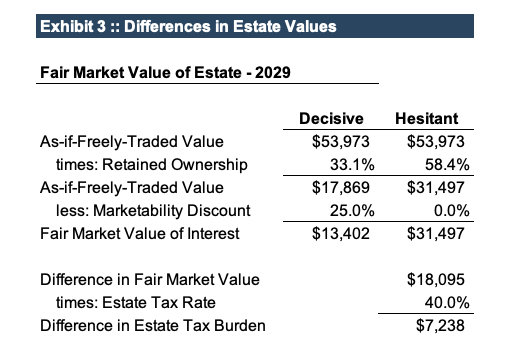

Because the gifts under the Decisive scenario were made while share prices were depressed because of the coronavirus, a larger portion of the shares were transferred than in the Hesitant scenario. As a result, the founder retained just 33% of the total shares after using the $12 million lifetime exclusion, compared with 58% under the Hesitant scenario. As shown in Exhibit 3, the effect on the resulting taxable estate is compounded because, under the Hesitant scenario, the 58% retained interest represents a controlling position in the shares and the value is not reduced for the marketability discount. In fact, although not shown in Exhibit 3, a control premium to the as-if-freely traded could be applicable, which would exacerbate the disparity.

In our example, failing to take advantage of the estate planning opportunity presented by the depressed asset prices added $7.2 million to the eventual estate tax bill. Procrastination can be costly.

Estate Planning and Control

Our preceding example was relatively simple. Estate planners often use a variety of strategies involving trusts and other vehicles to accomplish estate planning and other goals. However, our simple example illustrates what is often perceived as a “cost” to aggressive estate planning: the senior generation’s loss of voting control.

In the Decisive scenario, the founder’s ownership percentage fell below 50% in 2022. So, from that point on, the founder could no longer unilaterally make significant corporate decisions. We have seen a variety of strategies used to mitigate this outcome, such as establishing voting and non-voting share classes. These techniques can delay the eventual loss of control, but every business leader will eventually relinquish voting control of their company, whether through estate planning, death, or sale of the business.

In our experience, deferring estate planning to accommodate a desire to maintain voting control is rarely worthwhile. When the desire to maintain control is especially strong, that is often a clue that there are other underlying family issues that need to be addressed. If, as the controlling owner advances in age, the loss of voting control remains unpalatable, that could signal that the family dynamics are such that selling the business might be the best outcome for everyone.

Strike While the Iron Is Hot

Family business leaders are currently facing many pressing issues. Amid the uncertainty, however, family shareholders should know that the estate planning opportunities triggered by lower valuations may not last. Schedule a quick call with your estate planning advisers to see if there are steps you can take to help reduce the burden of future estate taxes on your family and business.

This article originally appeared in Family Business Magazine (April 2020) and was republished with permission.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director