Now That Focus Has Priced – Is It Pricey?

Sergio Marchionne was all smiles at Ferrari’s IPO in 2016 (photo from digitaltrends.com)

After Focus Financial filed their S-1 in May, I drew some analogies to Ferrari’s public offering two years ago (NYSE: RACE), as both companies faced considerable skepticism at advent of their IPO. Last week, the two stories intersected once again, as the man who steered Ferrari to its public offering, Sergio Marchionne, died unexpectedly at 66, and two days later Focus Financial went public (Nasdaq: FOCS).

Marchionne leaves behind an indelible imprint on the automobile industry. He almost single-handedly rebuilt the automotive landscape from its most unlikely corner, Italy, by squeezing $2 billion out of GM to recapitalize Fiat in 2005. With Fiat rescued from oblivion, Marchionne rebuilt Alfa Romeo, Maserati, and Ferrari under the Fiat umbrella. He took advantage of the credit crisis to bring Chrysler under Fiat’s control, and then took advantage of the subsequent bull market in luxury goods to take Ferrari public. He was trained as a lawyer, practiced as an accountant, and fueled by expresso and cigarettes. Above all, though, Signore Marchionne seemed to really love cars – something lacking in too many automotive executives these days.

I won’t go so far as to compare Focus Financial’s founder, Rudy Adolf, to Marchionne, but it’s worth noting that, like Marchionne, Adolf pulled off what many others have tried, and failed, to do. Now that Focus is public, we have a new channel with which to study and benchmark the industry. We have lots of questions, but for this post, we’ll just look at the implications of the Focus valuation that is consequent from the IPO.

Focus Is Richly Priced

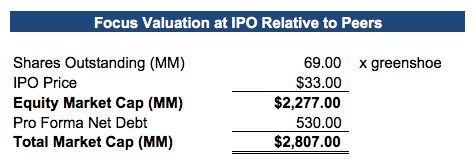

After a predicted pricing range of $35-39 per share, FOCS went public at $33. Of the $490 million raised in the offering (after underwriting fees), Focus is going to use a bit less than $400 million to pay down debt, about $35 million to settle equity compensation and other obligations to existing owners, and the remaining $60 plus million they’ll hold in cash for opportunities as they come along. If the underwriters exercise their greenshoe, Focus picks up another $75 million or so.

We heard plenty of chatter about the implications of Focus pricing below the originally suggested range, but we don’t make too much of it. The $35-39 range was very high (as we’ll get into later in this post), and in any event, the trading activity immediately raised Focus shares up to the range (no doubt guided by the invisible hands of market makers associated with the book runners). The IPO was a success.

Focus Didn’t Sell Cheap

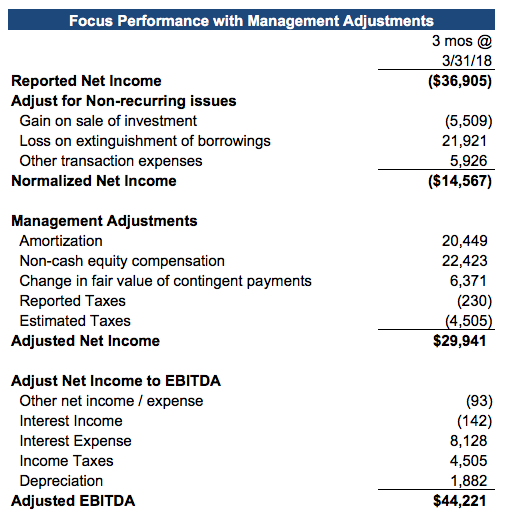

One thing we don’t have a question about is the magnitude of Focus’s valuation at IPO – it was expensive by any measure. In the quarter ending March 31, 2018, Focus reported a net loss of nearly $37 million on $196 million in revenue. In the prospectus, management provides a series of adjustments to redeem the quarterly loss to a net profit of almost $30 million and EBITDA of over $44 million.

We don’t take issue with many of management’s normalizing adjustments, as there are several non-recurring expenses associated with taking a company like Focus public. We are curious, though, about adding back non-cash equity compensation and the change in fair value of contingent consideration made for acquisitions. From the perspective of a shareholder, equity compensation is still a drain on earnings, because it dilutes existing shareholders’ claim on profitability. Since Focus is an acquisition company, it seems that any increased earn-out or other contingent payment expense increases the cost to Focus – whether in the form of cash or stock – such that these aren’t truly extraordinary items that a shareholder would disregard when calculating Focus’s profitability.

Any argument with these adjustments takes an already lofty IPO valuation for Focus to nosebleed levels. At the IPO price of $33 per share, Focus has an equity market cap (absent special allotments for the underwriters) of about $2.3 billion, and a total market capitalization inclusive of net debt of $2.8 billion.

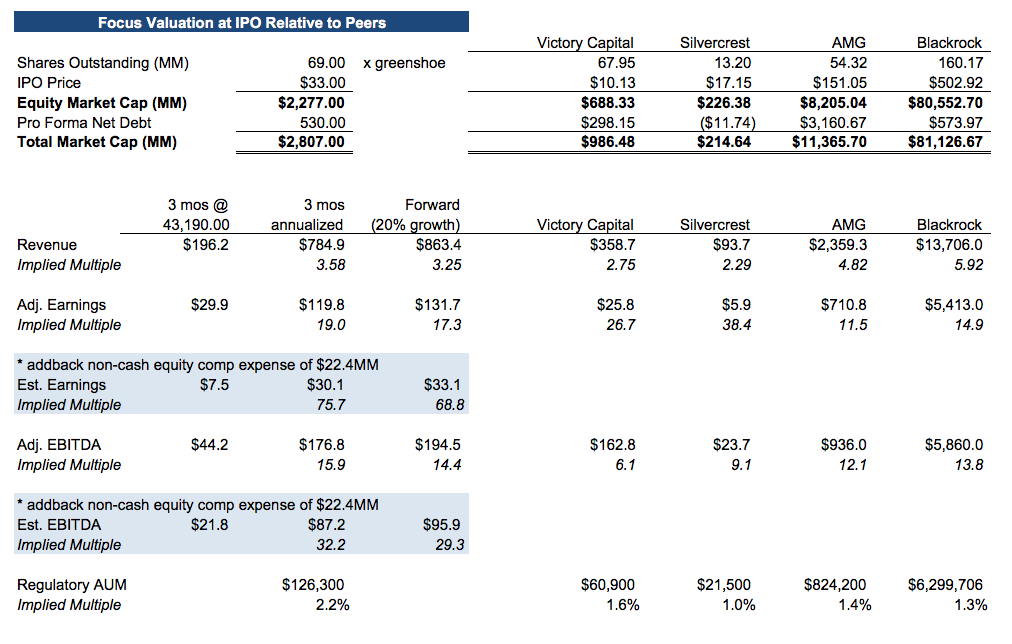

If we look at the most recent reported quarter, annualize it to develop a measure of ongoing performance and further look at a year forward assuming a 20% annualized growth rate (10% to the mid-year), we show strong multiples of revenue and earnings (compared to industry standards), and higher-than-usual multiples of EBITDA. However, that’s only if you accept all of management’s adjustments. If instead, you don’t give Focus the benefit of adding back non-cash (but nonetheless dilutive) equity compensation expense, the resulting multiples of profitability are other-worldly.

The big issue that most analysts seem to have with Focus is that they want to be given credit for inorganic growth on their multiple while adjusting earnings to eliminate the cost of that inorganic growth. The Focus prospectus and roadshow presentation made much of their 20% growth historical and prospective topline growth, and everyone knows that growth is because of acquisitions. The prospectus doesn’t actually offer any estimate of organic growth, or same-store sales growth, because they credit organic growth for subsidiary-level acquisitions by partner firms. It seems to us that the costs of that growth are, indeed, relevant to earnings. So either we judge Focus as an acquisition company or an operating company, rather than give them credit for the topline performance of an acquisition company and the bottom line performance of an operating company.

Peer Comparisons Are Difficult

Focus isn’t really an RIA, it holds preferred interests in profit sharing units in RIAs. Nonetheless, most analysts will lump them into the RIA space. The question is where?

Earlier this year a small RIA called Victory Capital went public (Nasdaq: VCTR). Victory is an amalgamation of wealth management firms and an ETF offering. It’s about half the size of Focus, and it hasn’t fared too well since the offering. Another possible comp is Silvercrest, which probably feels forgotten by the public markets in the wake of attention given to Focus. Since neither Victory nor Silvercrest are really RIA consolidators, Focus management probably wouldn’t appreciate the comparison to them. Neither Victory nor Silvercrest have shown the topline growth of Focus Financial, although Silvercrest’s growth isn’t that out of line with what Focus has produced organically – maybe even better.

While it’s difficult to find peers to compare Focus to, their valuation prices them more richly than even AMG. Is it reasonable to compare Focus to Blackrock? We don’t think so.

Pricing Implications

Most CEOs appreciate the market validating their strategy with high multiples, but high multiples are a double-edged sword. In the 1990s, I had a number of clients at Mercer Capital involved in roll-up corporations of one kind or other that went public. Some worked, and some didn’t. While Focus isn’t directly comparable to many consolidators, some of what has been observed in other industries holds true here as well.

High valuation multiples must be justified, and are often tested stringently with newer public companies. Focus promises high topline growth, with the implication that the profit margins will sort themselves out with scale over time. This is a common story for public companies in consolidating industries. The trouble comes when acquisitions are unavailable at reasonable terms or even accretive pricing, profits are uninspiring, and management feels pressured to do deals that don’t make sense just to demonstrate growth.

Based on their own disclosures, Focus will have to continue an aggressive acquisition strategy to achieve the 20% plus growth expectations that it has set for itself. If that growth is accomplished with new share issuances (as they have employed in the past), the market may not appreciate the dilution. Focus could, of course, pay cash, as they have a fair amount of it on hand following the IPO; but cash isn’t free either. What the market will eventually want to see – and several commentators have already mentioned this – is organic growth. If the firms that sold Focus some participation in their profitability grow their AUM from either existing or new clients, the fees should translate into profit growth that will accrue to Focus. The S-1 is curiously vague about Focus’s historical organic growth – defining it as inclusive of subsidiary-level acquisitions by partner firms. We question whether or not this is a true metric of organic growth, and in any event, the numbers Focus has posted with regard to this aren’t terribly impressive: 13.4% in 2017 and mid-single digit growth in the two years prior to that. We’ve written elsewhere that Focus will eventually have to prove itself as an operating model, and not just as an acquisition model. Their success or failure in this regard will be judged, at least in part, by demonstrated organic growth.

As for inorganic growth, Focus has interests, either directly or indirectly, in 140 plus firms. This leaves lots of room to grow in an industry with 15 thousand or so firms and a solid growth trajectory. If Focus stays priced at elevated multiples, it may raise expectations of sellers – especially in the circumstances where Focus is paying with stock. If, on the other hand, Focus shares settle to more normal multiples of profitability, sellers may be wary of selling into a downward trending share price. In some ways, it may be easier to attract acquisition candidates as a public company, but in others, it may be more challenging.

Margins are another matter. Most investment management firms benefit from operating leverage as they grow, and Focus has suggested the same opportunity exists for them as well. Our concern here is that Focus is not a small startup asset manager, they are a $126 billion manager with over 2,000 employees in their affiliated firms and fourteen years of history – yet their EBITDA margin (even on a highly-adjusted basis) hasn’t crested 25%. It’s possible that additional scale will improve this metric, but being a public company is labor intensive, as is tracking the activities of 140 plus partner firms, seeking out more, and seeking ways to improve the performance of existing firms. It may be difficult to assess the Focus margin against that of more typical RIAs, but as the Focus story unfolds, management will have to explain how to evaluate the effectiveness of the 70 or so employees at the holding company, what a reasonable cost of operations is, and how much profitability can be expected.

Nevertheless, They Did It

Setting all of my armchair quarterbacking aside, though, the fact remains that Rudy Adolf and his team pulled off what many have thought about but failed to do. The investing public now has a way to be involved in the profitability of the RIA phenomenon, and the RIA industry has a new funding source for transaction activity. Lots of questions remain, but if Sergio Marchionne could use the public markets to remake a moribund industry from a nation that isn’t terribly investor friendly, executing on the Focus business model should be an easy lap.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights