Put In An Order for More AAPL – But First, Let Me Take a Selfie!

Recently, Russia took on the awesome task of trying to deter rampant narcissism by opening a 24/7 helpline to support anyone thinking they might be addicted to photographing themselves – a selfie hotline – if you will. Russia’s Interior Ministry went to social media to educate its citizens on the dangers of taking selfies, which include falling down stairs, being attacked by wild animals, and being hit by trains. Selfie addiction, according to the Politburo, is very real and very dangerous.

Asset managers should take heed, and consider dialing in. Of all the concentration risks that an RIA faces, dependence on key staff ranks at or near the top. Unless you’ve taken the CFA Institute’s indoctrination (advice) and you just run an index fund (in which case, why are you competing with Vanguard?), your business is tied, sometimes to an extreme degree, to the persons who work with you, and maybe you yourself.

Talent is everywhere, yes, but clients who choose to invest with a given firm frequently do so, directly or indirectly, based on their confidence in the individual(s) who will be servicing their account and making their investments. The primary assets of an RIA “get on the elevator and go home at night,” and in our country (not sure about Russia), a firm can’t have title to individuals. Even with a non-compete.

That said, sometimes good people can be too good.

A sector asset manager investing in small cap equities for large institutional clients might be able to run $5 billion with twelve or fifteen people, of whom maybe five are actually involved in the investment research and portfolio management process. A comparable wealth management firm would require 100 employees or more to manage as much wealth. The fee schedules of the two shops might be similar, generating similar revenue streams. But margins are likely to be very different. A sector asset manager as we’ve described could generate twice the EBITDA margin off of the same revenue as the wealth management firm. High margins aren’t everything, though; which one would you rather own?

One paradox of value in an RIA is that the driver of growth in a firm, usually an individual, can also be its undoing (e.g. everyone’s favorite selfie-manager, Bill Gross). The small cap manager described above is at risk every time one of its portfolio managers crosses the street in traffic. High margins don’t always portend high valuations, because high margins can be hard to sustain. And, although it takes a strong personality to build an investment firm, that doesn’t mean it has to become an all-expenses-paid ego trip.

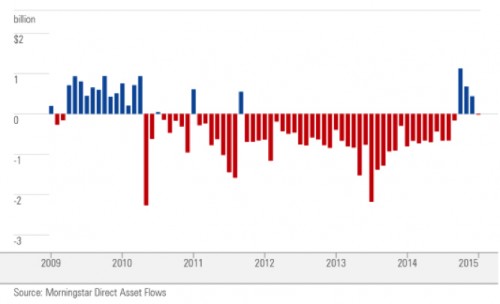

Consider the asset outflows around the time of Bill Gross’s departure from PIMCO.

Looking at the chart above, you would think PIMCO was insane to let Gross leave. Janus was clearly trying to reverse asset flow trends when it agreed to take in Gross despite his controversial personality.

And, of course, asset flows do have impact on value. PIMCO’s parent, Allianz, has pretty well underperformed Janus since Gross left.

It isn’t so much that Allianz has performed poorly, as that Gross woke things up a bit at Janus. That trend has shown remarkable endurance so far, but the message is clear that key staff and value are interactive in RIAs.

This simple fact has so many implications for asset managers that they’re hard to list, but here are a few.

- Compensation per capita at RIAs can be astronomical. The cure to this is typically to grow AUM faster than staff compensation. Indeed, the more successful a team is, the more assets they attract. This should (and often does) lead to operating leverage, but successful team members can command more compensation. Margins don’t grow forever.

- RIA transactions are frequently structured with as much as 25% to 50% of total consideration being paid in the form of an earn-out. This may cover some of the risk of client and product transition, but mostly it means that buyers and sellers share in that risk.

- Many capital providers who invest in RIAs don’t even try to cash out key employees, taking partial positions in the firms so that managers remain invested and economically tied to the firm.

- The profession is facing something of a physical cliff, as RIAs that began within a decade or so of the start of ERISA (1974) struggle to transition ownership from aging founders to the next generation. This is complicated by many things, most notably high valuations. It’s easy to quip that RIAs are worth so much no one can afford to buy them, but that’s a topic for another day.

Ideally, an RIA grows beyond the reputation and attributes of an individual or group of individuals and becomes a brand, such that clients come as much or more for the institution than the people. Easier said than done. But sustainability of the revenue stream over time has a big influence on value.

Of course, maybe the investing world will be taken over by index funds and robo-advisors. Until then, though, FINRA should consider installing a selfie hotline.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights