A “Grievous” Valuation Error: Tax Court Protects Boundaries of Fair Market Value in Grieve Decision

All fair market determinations involve assumptions regarding how buyers and sellers would behave in a transaction involving the subject asset. In a recent Tax Court case, the IRS appraiser applied a novel valuation rationale predicated on transactions that would occur involving assets other than the subject interests being valued. In its ruling, the Court concluded that this approach transgressed the boundaries of what may be assumed in a valuation.

Background

At issue in Grieve was the fair market value of non-voting Class B interests in two family LLCs.

- The first, Rabbit, owned a portfolio of marketable securities having a net asset value of approximately $9 million.

- The second, Angus, owned a portfolio of cash, private equity investments, and promissory notes having a net asset value of approximately $32 million.

Both Rabbit and Angus were capitalized with Class A voting and Class B non-voting interests. The Class A voting interests comprised 0.2% of the total economic interest in each entity. The Class A voting interests were owned by the taxpayer’s daughter, who exercised control over the investments and operations of the entities.

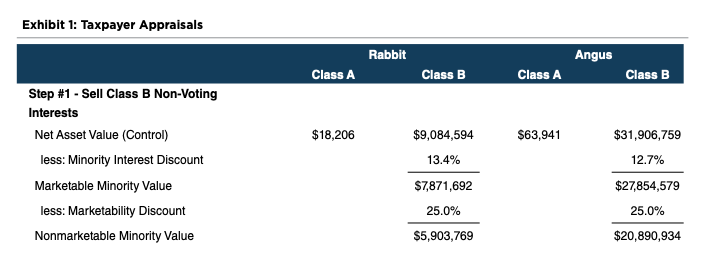

Valuation Conclusion – Taxpayer

The taxpayer measured the fair market value of the Class B non-voting interests using commonly accepted methods for family LLCs.

- The net asset value of each LLC was deemed to represent the value on a controlling interest basis.

- Since the subject Class B non-voting interests did not possess control over either entity, the net asset value was reduced by a minority interest discount. The taxpayer estimated the magnitude of the minority interest discount with reference to studies of minority shares in closed end funds.

- Unlike the minority shares in closed end funds, there was no active market for the Class B non-voting interests in Rabbit and Angus. As a result, the taxpayer applied a marketability discount to the marketable minority indication of value. The taxpayer estimated the marketability discount with reference to restricted stock studies.

The combined valuation discount applied to the Class B nonvoting interests was on the order of 35% for both Rabbit and Angus, as shown in Exhibit 1.

Valuation Conclusion – IRS

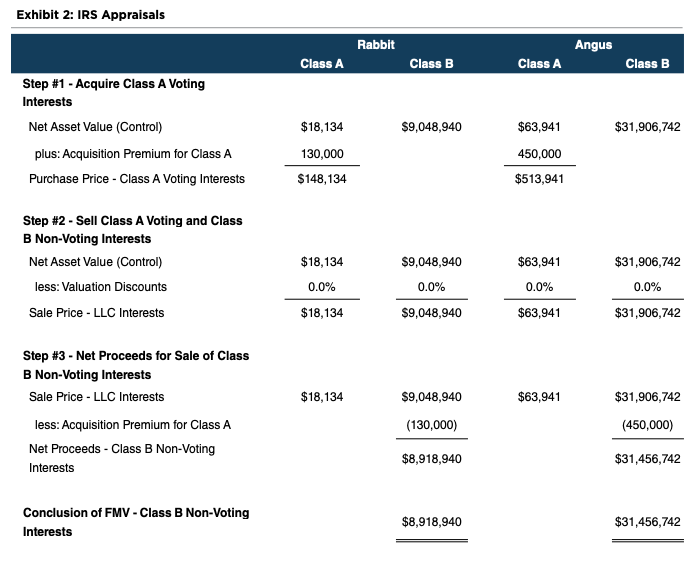

The IRS adopted a novel approach for determining the fair market value of the Class B non-voting interests.

Noting the disparity in economic interests between the Class A voting (0.2%) and Class B non-voting interests (99.8%), the IRS concluded that a hypothetical willing seller of the Class B non-voting interest would sell the subject interest only after having first acquired the Class A voting interest. Having done so, the owner of the class B non-voting interest could then sell both the Class A voting and Class B nonvoting interests in a single transaction, presumably for net asset value.

If the dollar amount paid of the premium paid for the Class A voting interest is less than the aggregate valuation discount applicable to the Class B non-voting interest, the hypothesized series of transactions would yield more net proceeds than simply selling the Class B non-voting interest by itself. The sequence of transactions assumed in the IRS determination of fair market value is summarized in Exhibit 2.

Tax Court Conclusion

It is certainly true that – if the Class A voting interests could, in fact, be acquired at the proposed prices – the sequence of transactions assumed by the IRS yield greater net proceeds for the owner of the subject Class B non-voting interests than a direct sale of those interests. However, is the assumed sequence of transactions proposed by the IRS consistent with fair market value?

The Tax Court concluded that the IRS valuation over-stepped the bounds of fair market value. The crux of the Court’s reasoning is summarized in a single sentence from the opinion: “We are looking at the value of the Class B Units on the date of the gifts and not the value of the class B units on the basis of subsequent events that, while within the realm of possibilities, are not reasonably probable, nor the value of the class A units.” Citing a 1934 Supreme Court decision (Olson), the Tax Court notes that “[e]lements affecting the value that depend upon events within the realm of possibility should not be considered if the events are not shown to be reasonably probable.” In view of the fact that (1) the owner of the Class A voting interests expressly denied any willingness to sell the units, (2) the speculative nature of the assumed premiums associated with purchase of those interests, and (3) the absence of any peer review or caselaw support for the IRS valuation methodology, the Tax Court concluded that the sequence of transactions proposed by the IRS were not reasonably probable. As a result, the Tax Court rejected the IRS valuations.

The Grieve decision is a positive outcome for taxpayers. In addition to affirming the propriety of traditional valuation approaches for minority interests in family LLCs, the decision clarified the boundaries of fair market value, rejecting a novel valuation approach that assumes specific attributes of the subject interest of the valuation that do not, in fact, exist. As the Court concluded, fair market value is determined by considering the motivations of willing buyers and sellers of the subject asset, and not the willing buyers and sellers of other assets.

Originally appeared in Value Matters™, Issue No. 3, 2020