Adjusted Earnings and Earning Power as the Base of the Valuation Pyramid

The extensive use of core versus reported earnings by public companies has been a widespread phenomenon for at least 25 years. During the past decade, the practice also has become widespread among companies (and their bankers who market deals) that are issuing debt in the leverage loan and high yield markets.

The practice is controversial. The SEC periodically will crack down on companies it thinks are pushing the envelope. Bank regulators have raised the issue of questionable adjustments to borrowers’ EBITDA for widely syndicated leverage loans.

Investors are aware of the issue, too, but have not demanded the practice to stop. In mid-2017, I attended a conference on private credit. One session dealt exclusively with adjusted EBITDA. One panelist offered that adjustments in the range of 5-10% of reported EBITDA were okay, but the consensus was the adjustments were out of control. Covenant Review reported that as of mid-2017 the average leverage for middle market LBOs over the prior two years was 5.5x based upon the target’s adjusted EBITDA compared to reported EBITDA of ~7x. The issue is no better, and perhaps worse, in 2018 judging from market sentiment.

If investors are solely relying upon company defined adjusted EBITDA, then they may be vacating their fiduciary duties when investing capital. That said, an analysis of core versus reported earnings is a critical element of any valuation or credit assessment of a non-early stage company with an established financial history.

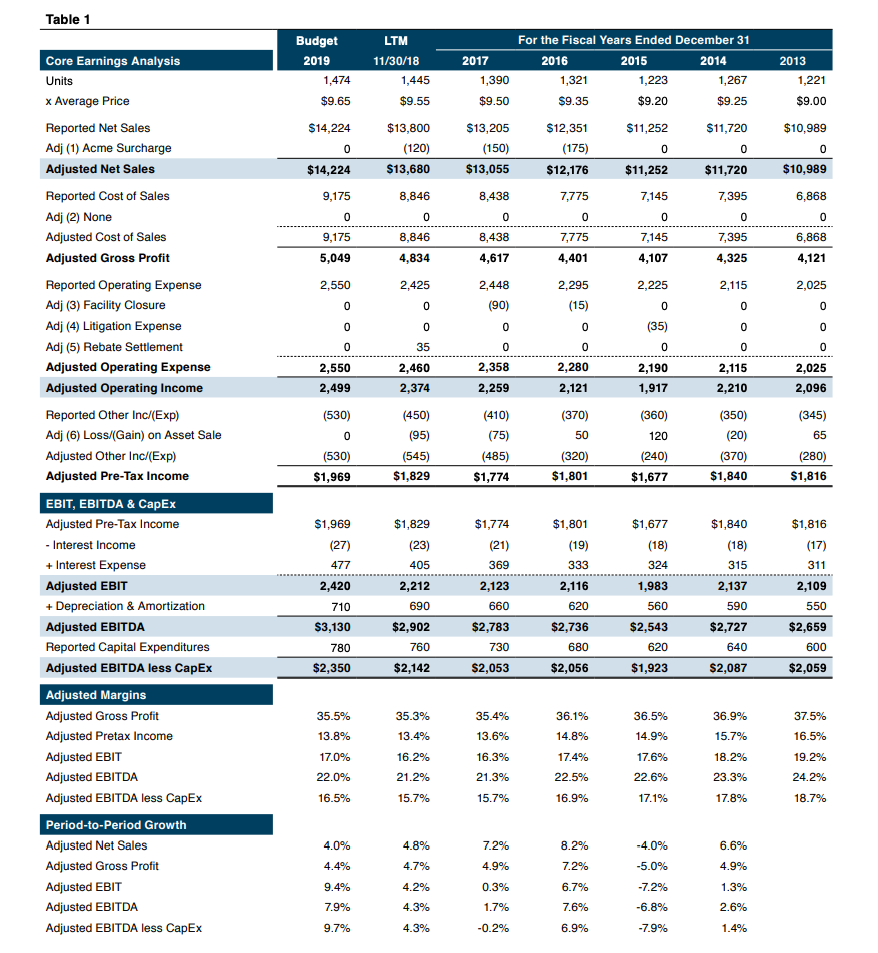

Table 1 below provides a sample overview of the template we use at Mercer Capital. The process is not intended to create an alternate reality; rather, it is designed to shed light on core trends about where the company has been and where it may be headed.

Adjustments

Adjustments typically consist of items that are non-recurring, unusual, and infrequent. They also may entail elements for a change in business operations, such as the addition of a new product or the discontinuation of a division. This is where judgment is particularly important because we have noticed a trend among some investors to credit businesses with future earnings for initiatives such as stepped-up hiring of revenue producers in which a favorable outcome is highly uncertain.

Minority vs. Control

Adjustments considered should take into account whether the valuation is on a minority interest or controlling interest basis. An adjustment for an unusual litigation expense will not be impacted by the level-of-value; however, other potential adjustments—particularly synergies a buyer could reasonably be expected to realize would only apply in a control valuation.

Core Trends vs. Peers

The development of the adjusted earnings analysis should allow one to identify the source of revenue growth and the trend in margins through a business cycle. The process also will facilitate comparisons with peers both historically and currently to thereby make further qualitative judgments about how the business is performing.

Out Year Budget vs. Adjusted History

The adjusted earnings history should create a bridge to next year’s budget, and the budget a bridge to multi-year projections. The basic question should be addressed: Does the historical trend in adjusted earnings lead one to conclude that the budget and multi-year projections are reasonable with the underlying premise that the adjustments applied are reasonable?

Core Earnings vs. Ongoing Earning Power

Core earnings differ from earning power. Core earnings represent earnings after adjustments are made for non-recurring items and the like in a particular year. Earning power represents a base earning measure that is representative through the firm’s (or industry’s) business cycle and, therefore, requires examination of adjusted earnings ideally over an entire business cycle. If the company has grown such that adjusted earnings several years ago are less relevant, then earning power can be derived from the product of a representative revenue measure such as the latest 12 months or even the budget and an average EBITDA margin over the business cycle.

Platform Companies/Roll-Ups

Companies that are executing a roll-up strategy can be particularly nettlesome from a valuation perspective because there typically is a string of acquisitions that require multiple adjustments for transaction related expenses and the expected earnings contribution of the targets. The math of adding and subtracting is straightforward, but what is usually lacking is seasoning in which a several year period without acquisitions can be observed in order to discern if past acquisitions have been accretive to earnings. Public market investors struggle with this phenomenon, too, but often the high growth profile of roll-ups will trump questions about earning power and what is an appropriate multiple until growth slows.

Income and Market-Based Valuation Approaches

In addition to providing insight into how a business is performing, the adjusted earnings statement will “feed” multiple valuation methods. These include the Discounted Cash Flow and Single Period Earning Power Capitalization Methods that fall under the Income Approach, and the Guideline (Public) Company and Guideline (M&A) Transaction Methods that constitute Market Approaches.

It may be obvious, but we believe an analysis of adjusted (and reported) earnings statements for a subject company over a multi-year period is a critical, if not the critical element, in valuing securities that are held in private equity and credit portfolios. Mercer Capital has nearly 40 years of experience in which tens of thousands of adjusted earnings statements have been created. Please call if we can help you value investments held in your portfolio.

Originally published in Mercer Capital’s Portfolio Valuation Newsletter.