Capital Conundrums

Capital raising efforts among financial institutions began in earnest in late 2007, primarily among money center banks and investment banks suffering under the weight of mark-to-market adjustments on various asset types. Banks with fewer assets marked to fair value through the income statement largely maintained sufficient capital to manage the initial wave of industry problems. However, the capital pressures intensified in 2008 as past-due levels and losses increased across a spectrum of loans tied to real estate, causing a number of banks to reassess their capital positions and, in some cases, to capitulate under the weight of the external environment and seek out additional capital.

This article provides a summary of capital raising transactions that have occurred in 2008 and offers insight into the financial considerations present in evaluating each capital alternative. These considerations are relevant whether a bank is in the position of raising capital to buttress the balance sheet or, alternatively, has an opportunity to make an investment in another bank facing a capital shortfall.

Common Stock

The surest way to shore-up capital ratios is through the issuance of common stock, which places no pressure on the company’s cash flow if no dividends are declared. The primary disadvantage of common stock offerings is the dilution that current shareholders may experience to their ownership positions and future earnings per share.

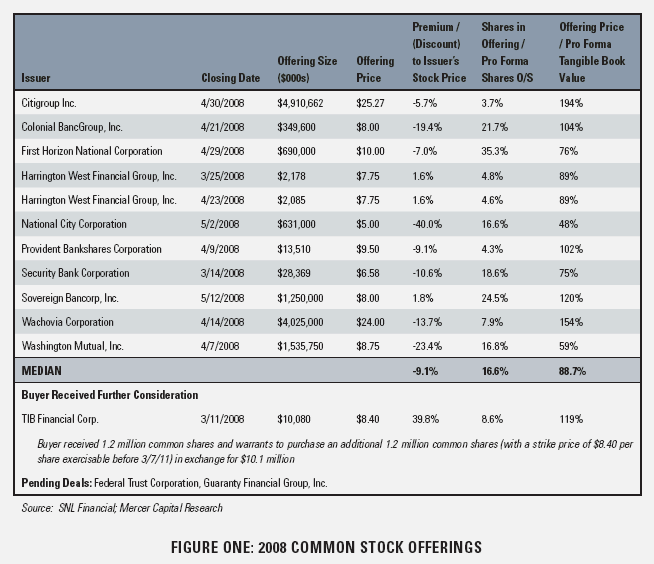

Figure One indicates recent common stock offerings. Most of the issuances have occurred at discounts to the issuer’s stock price prior to the transaction. In one-half of the issuances, the offering price for the common stock was less than pro forma tangible book value per share (existing tangible book value, plus the equity raised in the offering). One recent article noted that investors were potentially willing to purchase stock at tangible book value per share, as adjusted to reflect the investors’ estimate of expected losses in the loan portfolio.

In considering a common stock issuance, important questions for community banks to consider include:

- How should the transaction be structured? Should the bank conduct a subscription rights offering to existing shareholders? Should the bank attempt to sell stock to a small number of new investors who may bring additional expertise to the bank?

- What perquisites of control, such as board seats, should the new investors possess?

- What share price balances the need to raise capital with the goal of minimizing dilution to the existing shareholders? In setting the price, how does the bank bridge any gap between the investor’s assumptions about potential losses inherent in the portfolio with bank management’s estimates of such losses?

- Should other incentives, such as warrants, be included in the “package” offered to investors?

Preferred Stock

Depending on its structure, preferred stock can bear a resemblance to either long-term debt or equity. In its simplest form, “straight” preferred stock economically resembles long-term debt with either fixed or floating rate payments. Convertible preferred stock is a hybrid instrument that combines elements of both debt and equity. Generally, convertible preferred stock has a lower dividend rate than straight preferred stock, but a higher yield than common stock. To compensate investors for accepting the lower current return, the investors receive the right to participate in the appreciation of the common stock. Further, preferred stock dividends can be either cumulative (meaning that dividends are accrued in the intent of paying such dividends later) or noncumulative.

From a bank’s perspective the advantages of preferred stock include:

- Tier 1 capital treatment of the proceeds. No formal limits exist on the amount of non-cumulative preferred stock that a bank may include in Tier 1 capital, although certain informal limits exist on a bank’s reliance on non-voting equity, such as preferred stock. Cumulative preferred stock is includible in Tier 1 capital, subject to certain limits;

- For straight preferred stock, the avoidance of dilution caused by issuing common stock; and,

- For convertible preferred stock, a potentially lower dividend rate than obtainable by issuing straight preferred stock or subordinated debt.

Potential disadvantages from a bank’s perspective include:

- The cash flow requirements to service the dividend payments; and,

- The lack of tax deductibility of the dividend payments.

From an investor’s perspective, preferred stock can be an attractive alternative to common stock. For convertible preferred stock, the investor may receive a dividend in excess of the common stock’s dividend, plus the right to enjoy appreciation in the underlying common stock. Thus, the higher dividend protects the investor’s downside (to the extent the issuer actually pays the dividend). Further, if the investor is a corporation, the tax deduction for dividends received may be available.

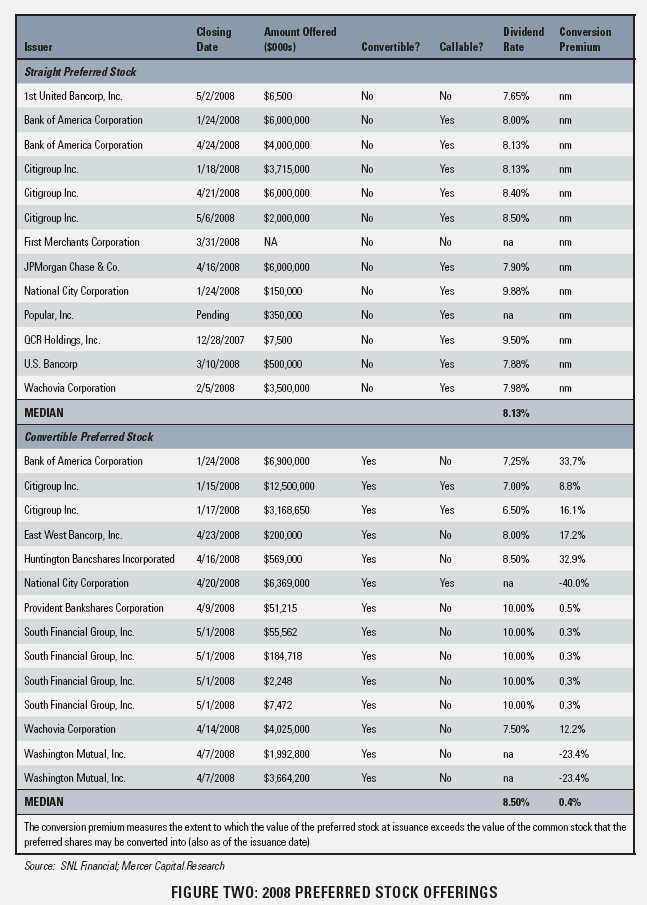

Preferred stocks have been a popular capital raising tool in the present environment, owing to their flexibility and the downside protection afforded to investors. Figure Two indicates issuances announced during 2008.

When structuring a preferred stock issuance, important considerations include:

- What is the appropriate dividend rate? This depends, in part, on the type of preferred stock (straight or convertible). In addition, the perceived credit quality of the issuer is of paramount importance – compare the 9.88% rate on National City’s issuance to the 7.88% rate on U.S. Bancorp’s offering.Ordinarily, dividend rates on convertible preferred stocks are lower than straight issuances. While this is true for individual issuers (note, for instance, the difference in the dividend rates on Citigroup’s straight and convertible issuances), it is not true for the group of recent issuances as a whole. Several convertible issues contain dividend rates of 10% – higher than any straight issuances. This likely reflects the perceived financial condition of the issuers and the resulting difficulty in accessing the capital markets.

- For convertible issues, what is the appropriate conversion premium? At the date the preferred stock is issued, the conversion premium measures the extent to which the issuance price of the preferred stock (generally its par value) exceeds the value of the common stock into which the investor may convert the preferred shares. For instance, consider a preferred stock with a par value of $1,000 that can be converted into 20 shares. This implies that the conversion price is $50 ($1,000 / 20 shares). If the value of the common stock on that date was $50 as well, then the conversion premium is 0%. Generally, conversion premiums are greater than 0%, meaning that the common stock must appreciate before conversion becomes financially attractive.Issuing banks prefer higher conversion premiums, because fewer shares will be issued upon conversion. Continuing the preceding example, if the conversion premium is 20%, the conversion price would be $60 ($50 common stock price x 1.20). Then, upon conversion, the bank would issue only 16.7 shares ($1,000 par value / $60 conversion price). Conversely, investors prefer lower conversion premiums.

From an issuer’s perspective, the most unattractive terms include a high dividend rate and a low conversion premium. As an example, consider South Financial Group’s May offering of 10% preferred stock with a 0.3% conversion premium.

- Should the preferred stock investors receive voting rights? Of the issues analyzed, only the National City issuance granted voting rights to investors.

- Are the dividends cumulative? This affects the capital treatment of the proceeds, as well as the potential return required by an investor.

- Do the terms of the issuance meet applicable regulatory guidance for consideration in Tier 1 capital? Regulatory capital guidance contains a number of considerations that can affect the capital treatment of the offering. For instance, structures that create an incentive for the bank to redeem the preferred stock for cash, particularly in times of financial distress, may not be includible in capital.

Trust Preferred Securities

Trust preferred securities are a hybrid instrument, combining the tax treatment of debt and the Tier 1 capital treatment of equity. From a bank’s perspective, the favorable after-tax cost of capital represents one of the primary advantages. Prior to late 2007, another significant advantage of trust preferred securities was that community banks could easily access the capital markets by participating in one of the pooled offerings underwritten by investment banks. As conditions in the credit markets deteriorated, this advantage disappeared, as the pooled offerings have largely vanished from the marketplace, although they may eventually return if investor demand improves.

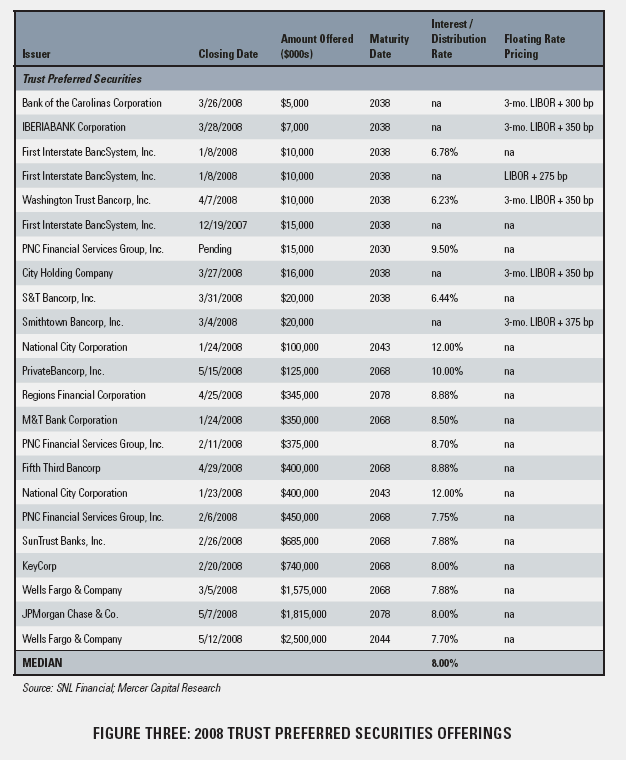

Figure Three indicates data on trust preferred securities offerings announced in 2008 by publicly traded banks. While pooled offerings have not occurred in 2008, several smaller publicly traded banks have placed trust preferred securities with institutional investors. The pricing in these offerings has increased since the last pooled offerings, which often contained spreads in the range of 150 basis points over LIBOR. The variable rate offerings indicated in the table contain spreads in the range of 350 basis points over LIBOR.

While the availability of trust preferred securities through pooled offerings is currently uncertain, other investors may exist. Alternatively, banks can consider issuing trust preferred securities to local investors or shareholders. Although this type of offering may require more time and professional fees than a pooled offering, the bank will still enjoy the significant tax and capital benefits of trust preferred securities. Questions to consider for banks include:

- If the bank issues securities to local investors, what is an appropriate rate? This would involve, among other considerations, the structure of the offering (e.g., fixed versus floating rate payments), credit quality (e.g., the capital ratios and loan quality of the issuer), the interest rate environment, and market pricing of comparable instruments.

- What are the capital implications? While current capital rules permit a bank to include trust preferred securities in Tier 1 capital, these rules will eventually be tightened. Currently, the capital rules limit trust preferred securities to 25% of “core capital elements.” Eventually, “core capital elements” will exclude goodwill, thus reducing the amount of qualifying trust preferred securities for institutions with goodwill.

Subordinated Debentures

In the event that the bank needs to raise Tier 2 capital, instead of Tier 1 capital, subordinated debentures may be desirable. Subordinated debentures may be included in Tier 2 capital, subject to a limitation equal to 50% of Tier 1 capital. Like trust preferred securities, interest payments on subordinated debentures are tax deductible. Subordinated debentures can be issued at the subsidiary bank level, which may decrease their credit risk for investors, relative to instruments that require the holding company to maintain sufficient liquidity from bank dividends or other sources of funds.

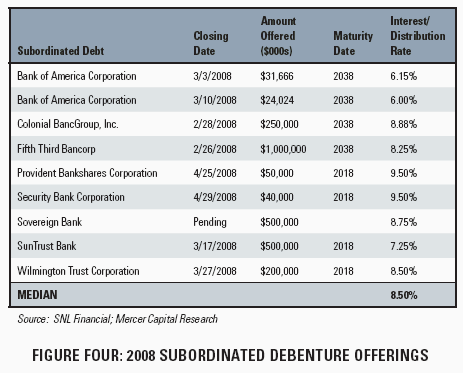

Figure Four indicates the pricing of subordinated debenture offerings in 2008. While few community banks are included in this group of offerings, subordinated debentures may remain an attractive alternative to curing a Tier 2 capital need. Transactions announced in April and May have occurred at interest rates ranging from 8.75% to 9.50%. All of the issuances have involved either ten or thirty year terms.

For community banks where subordinated debentures may solve a problem, the following questions should be considered:

- What is the interest rate? Similar to trust preferred securities, an analysis should consider market interest rates, rates on similar subordinated debentures, and the credit quality of the issuer.

- What is the capital treatment? Subordinated debentures have various capital limits and phase-outs. Over the last five years of the debenture’s maturity, the amount includible in Tier 2 capital declines by 20% per year. In addition, the amount of subordinated debentures includible in Tier 2 capital is limited to 50% of Tier 1 capital. To the extent that the new capital guidelines limit the amount of trust preferred securities includible in Tier 1 capital, banks may find a portion of their trust preferred securities now included in Tier 2 capital. In that case, the trust preferred securities and subordinated debentures would collectively be subject to the 50% limit.

Conclusion

For community banks needing capital, the alternatives possess substantially different impacts on existing shareholders and the bank’s future returns, not to mention divergent capital treatments. For potential investors in community banks, downside protection is important in the present environment. As a result, recent capital raises have included common stock issued at discounts to the issuer’s market price and convertible preferred stock issuances with relatively high dividend rates and low conversion premiums.

Mercer Capital can assist community banks and investors with considering the advantages and disadvantages of the spectrum of capital instruments available to a particular bank, focusing on their effects on existing shareholders and future shareholder returns, as well as evaluating the pro forma capital impact of different instruments and offering amounts. We can also assist banks and investors in determining an appropriate stock price or interest rate in offerings sold to local investors, analyzing, from an investor’s standpoint, the advantages and disadvantages of different proposed investment structures, and providing fairness opinions that the capital offering is fair to a specified group of shareholders.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch 2008-05, published May 28, 2008.