Community Bank Valuation (Part 3): Important Relationships Between a Bank and Its Holding Company

The August 2019 BankWatch described key considerations in analyzing the financial statements of banks. However, we did not address one crucial set of relationships – those between a bank holding company (“BHC”) and its subsidiary depository institution.

Most banks are owned by bank holding companies. While investors often state that they own an interest in a bank, this may not be legally precise. Usually, they own a share of stock in a bank holding company, which in turn owns a controlling interest in a subsidiary bank’s common stock. Where a bank holding company exists, this entity’s common stock generally is the subject of valuation analyses.

Part 3 of the Community Bank Valuation series explores important relationships between banks and their holding companies, focusing particularly on cash flow and leverage.

The Holding Company’s Balance Sheet

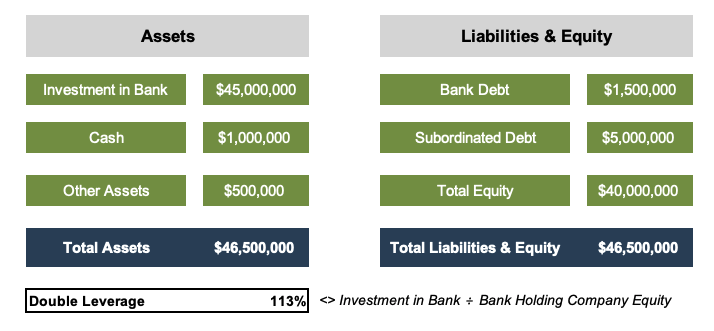

Compared to a bank’s balance sheet, a holding company’s balance sheet has fewer moving parts. The “left side” of its balance sheet, or its assets, usually is rather boring. The more intriguing analytical question, though, is how the bank holding company finances its investment in the bank. The following table presents a balance sheet for a BHC controlling 100% of the common stock of a bank with $500 million of total assets.

Usually, the holding company’s assets consist virtually entirely of its investment in its subsidiary bank or banks, which equals the bank’s total equity. The investment in the bank is carried at equity, meaning that it increases by the bank’s net income and decreases by dividends paid from the bank to the holding company, among other transactions. Other material assets may include:

- Cash. BHCs with cash obligations paid at the holding company, such as interest payments or compensation, often will maintain a cash buffer to cover several months of operating expenses. In some cases, BHCs will maintain a larger cash position to react opportunistically if the bank subsidiary needs a capital injection for its growth or to repurchase BHC shares.

- Other Assets. Non-bank assets typically are relatively modest and consist of investments in other entities (such as an insurance agency), intangible assets related to acquisitions that were not “pushed down” to the subsidiary, or facilities. In periods marked by higher levels of nonperforming assets, BHCs may hold problem assets, which is one strategy to reduce the bank’s classified asset/ capital ratio.

Interestingly, BHCs can borrow from banks – just not their bank subsidiary – and other capital providers. If the funds are downstreamed into the bank, the borrowings can be transformed from an instrument not includible in the BHC’s regulatory capital into Tier 1 capital at the bank. In order of seniority these funding sources include:

- Bank Stock Loans. These loans are collateralized by the subsidiary bank’s stock and typically are obtained from another bank. As a secured borrowing, these loans generally have a lower cost than other alternatives. However, in the event of a default, the lender can foreclose on their collateral (i.e., the bank stock).

- Subordinated Debt. After passage of the Dodd-Frank Act and the Basel III capital regulations, subordinated debt became a more prominent funding source, usually for organic growth or acquisitions. Various regulatory requirements govern subordinated debt offerings, but most community bank placements provide for a ten year term with the interest rate fixed for five years. The securities may be considered Tier 2 capital for the holding company.

- Trust Preferred Securities (“TruPS”). TruPS were created in the 1990s to combine the Tier 1 capital treatment of preferred stock with the tax deductibility of debt. Rightly or wrongly, this instrument was viewed negatively by some regulators after the financial crisis, and the Basel III regulations effectively nullified new issuances. Many BHCs still hold grandfathered TruPS, though, which often do not mature until the 2030s. TruPS generally have interest rates that float with LIBOR, are subordinated to all other BHC obligations, and provide the issuer the right to defer payments for up to five years without triggering a default. TruPS count as Tier 1 capital for BHCs with under $15 billion in assets that are considered to be “large” BHCs that fie Y-9LP and Y-9C call reports with the Federal Reserve.

A BHC’s equity usually consists almost entirely of common stock, which generally must be the principal form of capitalization under BHC regulations. However, BHCs can issue preferred stock, and regulations view most favorably non-cumulative, perpetual preferred stock.

Analytical Considerations

Why do holding companies exist? First, they provide an efficient way to raise funds that can be injected as capital into the bank, thereby accommodating its organic growth. Second, they can facilitate acquisitions. Third, BHCs can more efficiently conduct shareholder transactions, such as repurchases.

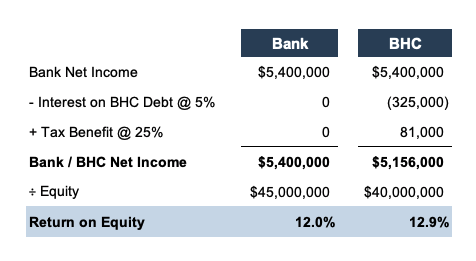

By using leverage, a BHC can enhance the bank’s stand-alone return on equity (or exacerbate the ROE pressure arising from adverse financial scenarios). As indicated in Table 2, BHC leverage magnifies the subsidiary bank’s 12.0% ROE to 12.9% after considering the cost of the BHC’s debt.

As for a non-financial company, too much leverage can mean that the beneficial effect to shareholders of a higher ROE is swamped by the additional risk of financial distress. Various metrics exist to measure the holding company’s leverage, but one is the “double leverage” ratio, which is calculated as the investment in the bank subsidiary divided by the BHC’s equity. As indicated in Table 1 on page one, the BHC’s ratio is 113%, which is consistent with the median reported by all smaller BHCs at June 30, 2019 (112%, excluding some BHCs for which the BHC’s equity exceeds the bank investment).

Cash Flow

Unfortunately, BHC regulatory filings and audited financial statements do not provide a sources and uses of funds schedule, although some cash flow data is provided. Nevertheless, understanding the BHC’s obligations, and the cash required to service those obligations, is essential.

Sources of funds consist principally of the following:

- Dividends from the bank subsidiary. The depth of this source of cash flow should be evaluated in light of the bank’s profitability, capital levels, and growth opportunities.

- Debt issuances

- Common stock sales

- Intercompany payments. For example, the bank may reimburse the holding company for certain expenses paid by the BHC. Additionally, banks and BHCs often have tax-sharing arrangements. If the holding company incurs expenses, then it may realize an offsetting tax benefit.

Uses of funds include the following:

- Debt service

- Shareholder dividends

- Share repurchases

- Operating expenses. Expenses such as compensation, directors’ fees, and certain insurance premiums may be recorded by the holding company

Analysts should compare a bank’s ability to pay dividends, given its profitability level and need to retain earnings to fund its growth, against the BHC’s various claims on cash. Mismatches can sometimes arise due to changes in the bank’s performance or operating strategy. For example, consider a BHC that historically has paid high dividends to shareholders. If its subsidiary bank adopts a new strategic plan focused on organic growth, then the bank will need to retain earnings rather than pay dividends to the BHC and, ultimately, BHC shareholders. Additional borrowings could fund a short-term gap, but this is not a long-term solution to a BHC cash flow mismatch.

Two other special circumstances arise when analyzing BHC cash flow:

- Acquisitions. Prior to entering into a transaction, the BHC’s plan for funding any cash consideration should evaluate the availability and desirability of dividends from the bank, debt offerings, and stock sales. Further, the cash acquired from the target BHC may provide another source of transaction funding.

- S Corporations. Shareholders in an S corporation rely on the BHC for distributions to offset their pass-through tax liability, while the BHC in turn relies on the bank for dividends to fund those tax payments. There are no special capital rules at the bank level that provide flexibility regarding the payment of dividends to offset BHC shareholders’ tax liability when other restrictions on dividends may exist. That is, C corporation and S corporation banks face the same capital regulations. Boards of S corporations may desire to operate, at the margin, with a greater capital buffer to avoid a situation where the shareholders have taxable income but the BHC is unable to make distributions.

Capital

Capital requirements for BHCs vary based upon their asset size. Under current regulations, BHCs with assets below $3.0 billion are subject to the Federal Reserve’s Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement. This regulation does not establish any specific minimum capital ratios for small BHCs; however, a debt/ equity ratio limitation exists for debt arising from acquisitions. Therefore, small BHCs have significant flexibility in managing their capital structure, although the Federal Reserve theoretically remains a check on their creativity.

Large BHCs are subject to the Basel III regulations, which involve capital ratios calculated based on Tier 1 and total capital. Tier 1 capital generally is limited to common equity, non-cumulative perpetual preferred stock, and grandfathered TruPS. In addition to the allowance for loan losses, Tier 2 capital may include subordinated debt. Large BHC management can balance these capital sources to minimize the BHC’s weighted average cost of capital, maintain flexibility for unexpected events or opportunities, and ensure compliance with regulatory expectations.

Conclusion

While the subsidiary bank receives most of the analytical attention, the holding company on a standalone (or parent company) basis should not be overlooked. This is particularly true if the holding company has significant obligations to service debt or pay other expenses. By understanding the linkages between the bank and holding company, analysts can better assess a BHC’s potential future returns to shareholders and risk factors posed by the BHC that could jeopardize those returns.

Originally published in Bank Watch, September 2019.