Fed Rate Cut(s) – Now What?

Rate cycles are predictable in one sense: a period of falling rates tends to follow a period of rising rates. The opposite is true, too. How much and how long the cycle will take are questions to ask, but are unknowable. Another question to ponder is whether the Fed leads or follows the market, when setting its short-term policy rates.

Now that the pandemic interest rate cycle is complete (rate cuts in 2020, rate hikes in 2022-2023) and a new “downrate” cycle has begun. We take a high-level look at changes in yields, cost of funds (COF) and net interest margins (NIM) from past cycles to gauge how he unfolding downrate cycle may impact margins.

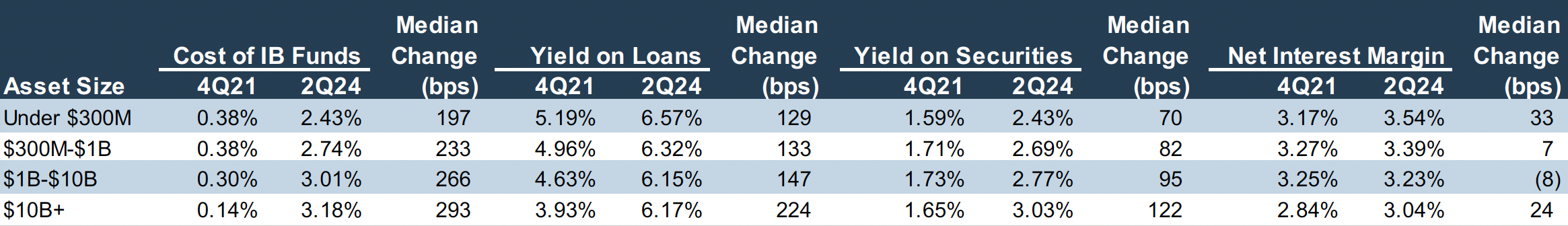

The figure below details the change in COFs and yields from the last quarter before the Fed began to raise rates (4Q21) and 2Q24 – the last quarter before the Fed initiated the first of what presumably will be multiple cuts by reducing its policy rates by 50 basis points (bps) in mid-September. As an aside, the increase of ~50bps in long-term U.S. Treasury yields and ~$200/ounce in gold since the cut implies the downrate cycle may be limited.

Click here to expand the image above

By way of reference, immediately before the first hike in March 2022, the Fed funds target rate was 0.00-0.25%, bank prime was 3.25%, and the 10-year Treasury yielded ~2%. Before the Fed cut in mid-September, the fed funds range was 5.25-5.50%, the bank prime was 8.5%, and the 10-year Treasury yielded ~3.7%.

As shown below, there is a direct correlation between asset size and cost of interest-bearing funds. Larger banks reported a higher cost of funds in 2Q24, presumably given the competitive nature of more urban markets and greater reliance on wholesale funding whereas smaller banks arguably have somewhat less competition and are less reliant on wholesale funding. Small banks reported a lower increase in cost of funds between 4Q21 and 2Q24 of ~200bps compared to ~300bps for large banks (note: the FDIC defines community banks as having assets less than $10 billion).

The increase in funding costs also occurred against the backdrop of a flood of liquidity into the banking system during 2020 and 2021. This left the spread between deposit rates and short-term market yields unusually wide on the eve of the failure of SVB, that in turn forced most banks to aggressively reprice deposits.

As for loan yields, smaller banks reported a higher yield in 2Q24 as larger markets are more competitive and pricing is tighter. Larger banks reported a more substantial increase in loan yield between 4Q21 and 2Q24, primarily given more loans with a base rate tied to SOFR. Yield on securities were all relatively similar in 4Q21 but increased more for larger banks for several reasons (shorter maturities, greater willingness to take losses to reposition the portfolio, etc.).

Consistent with history, NIM was highest for small banks and was lowest for large banks in 2Q24. Interestingly, the bookends were the biggest beneficiaries in terms of margin expansion during the most recent up rate cycle.

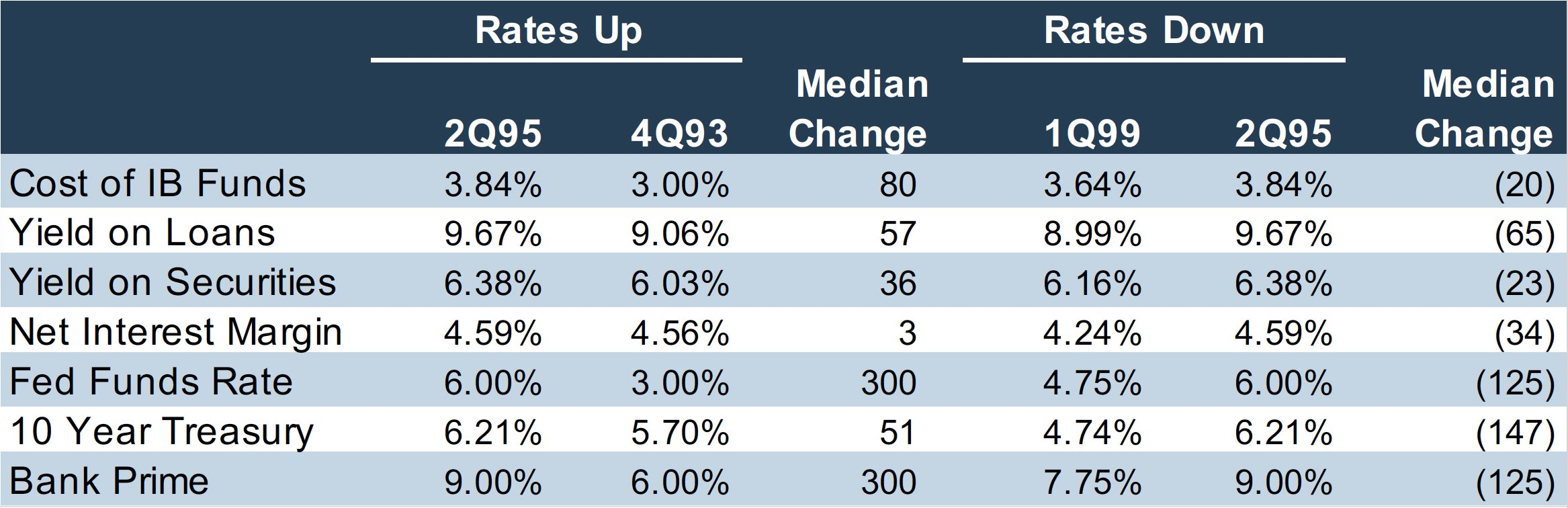

The next figure provides a look at the change in the COF, yields and NIMs during the up rate cycle of 1994 and subsequent down rate cycle of 2Q95 to 1Q99. Although the Fed hiked its policy rates 300bps in a little over 12 months and thereby produced a ferocious bond bear market in 1994, bank fundamentals remained solid given a backdrop of a growing economy and stable real estate values. The median change in the COF was 80bps while the median yield on loans increased 57bps. However, the delta between bank prime rate and yield on loans tightened from 4Q93 (~300bps) to 2Q95 (~70bps). Net interest margin was approximately flat between time periods.

Between 2Q95 and 1Q99 the Fed lowered the policy rate 125bps as inflationary pressures receded (1995-96) and later as the global currency and LTCM crisis took hold (1998). For banks, this resulted in a modest COF reduction (20bps lower) while loan yields declined more significantly (65bps) which resulted in a lower NIM for the industry.

After the dotcom bubble burst in 2000, the Fed cut its policy rate to 1.0% and thereby ignited a housing bubble that eventually popped in the 425bps hiking cycle of 2004-2006, which in turn was the catalyst for cuts that ended with a zero interest rate policy—ZIRP—in December 2008.

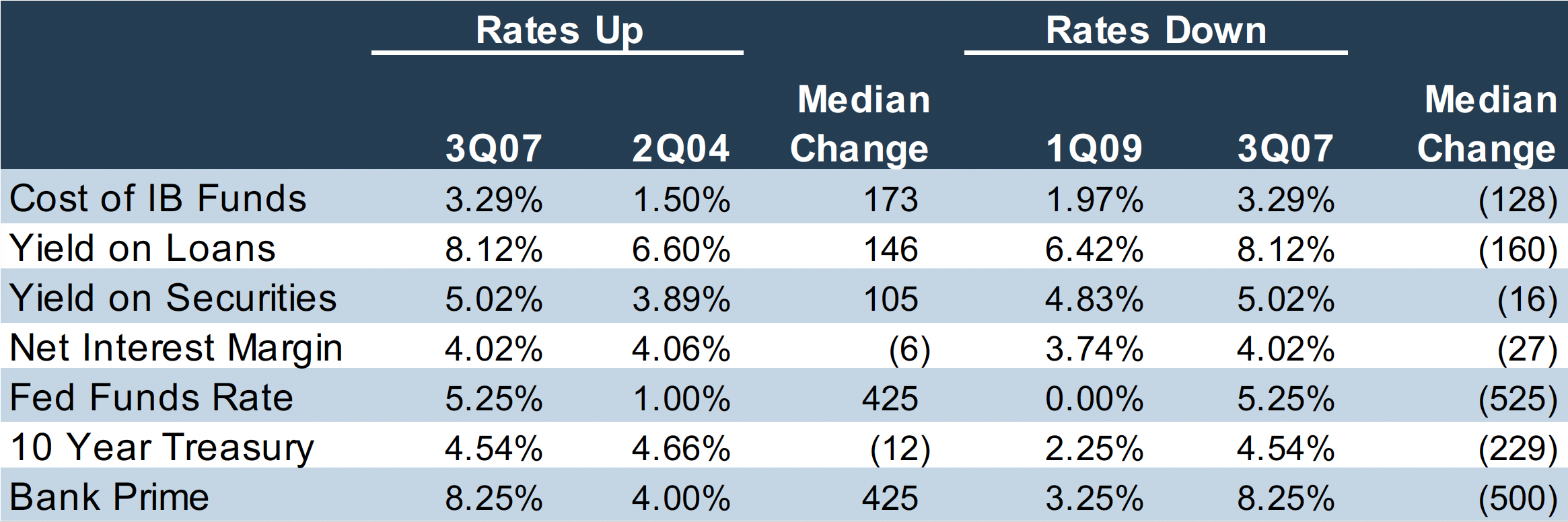

In our last figure, we compare changes in the COF/yields/NIM between 2Q04 before the first hike with 3Q07 immediately before the first cut as the disaster begins to unfold, and then 3Q07 with 1Q09 after ZIRP was implemented.

The median change in the COF was 173 basis points between 2Q04 and 3Q07, while yield on loans increased 146 bps and NIM was flattish. Similar to the 1990s scenario discussed previously, the delta between loan yield and bank prime tightened during the uprate cycle while the increase in COF was less than half of the increase in fed funds rates.

What began with a 50bps rate cut in the fall of 2007 eventually increased to a 525bps reduction by year-end 2008. By 1Q09, the median COF reduction was 128bps while loan yields fell 160bps. The result was a median reduction in the NIM of 27bps. However, our measurement period does not do justice to the impact of ZIRP on NIMs in which the value of NIB deposits were crushed vs a “normal” environment when short-term rates are in the vicinity of 4%. Over the next several years, NIMs would decline as asset yields fell much more than funding costs.

Where from here? We do not know for sure, but bank investors are optimistic that Fed rate cuts will allow banks to cut their COFs more than yields decline and thereby produce limited margin expansion after a period of margin pressure due to the need to aggressively reprice deposits post-SVB.

Count us as skeptical – besides the data is nuanced as are individual bank balance sheets.

For both cycles (1990s and pre-GFC 2000s), NIM was flat on the way up but declined in down rate scenarios. During 2Q22-1Q23, bank NIMs expanded as banks sat on deposit rates as yields rose with 525bps of Fed hikes. Since 2Q23, NIMs trended lower until what appeared to be emerging stability with initial 3Q24 earnings reports. It may be that limited Fed cuts over the balance of the current down rate cycle may be neutral for NIMs, whereas if the Fed is forced to cut sharply for whatever reason will produce lower NIMs in time.