Jones v. Commissioner

Estate of Aaron U. Jones v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2019-101

(August 19, 2019)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In May 2009, Aaron U. Jones made gifts to his three daughters, as well as to trusts for their benefit, of interests (voting and non-voting) from two family owned companies, Seneca Jones Timber Co. (SJTC), an S corporation, and Seneca Sawmill Co. (SSC), a limited partnership. These gifts were reported on his gift tax return with a total value of approximately $21 million. The IRS asserted a gift tax deficiency of approximately $45 million on a valuation of approximately $120 million. The Tax Court ruled that value was approximately $24 million, agreeing with the taxpayer’s appraiser.

In this case, the Tax Court again concluded that “tax-affecting” earnings of an S corporation was appropriate in determining value under the income method (see also Mercer Capital’s review of the Kress decision). However, there are several other issues of interest in this case which we discuss further in this article.

BACKGROUND

SSC was established in 1954 in Oregon as a lumber manufacturer. SSC operated two saw mills – its dimension and stud mill – delivering high quality products that were technologically advanced, allowing SSC to demand a higher price for its products than its competitors. Early in its history, SSC acquired most of its lumber from Federal timberlands. As environmental regulations increased, SSC’s access to Federal timberlands became at risk. Mr. Jones began purchasing timberland in the late 1980s and early 1990s when he became convinced that SSC could no longer rely on timber from Federal lands.

SJTC was formed as an Oregon limited partnership in 1992 by the contribution of those timberlands purchased by Mr. Jones. SJTC’s timberlands were intended to be SSC’s inventory. Further, both SSC and SJTC maintained similar ownership groups, with SSC serving as the 10% general partner of SJTC. As of the date of valuation, SJTC held approximately 1.45 million board feet of timber over 165,000 acres in western Oregon, most of which was acquired in those initial purchases between 1989 and 1992. In 2008, approximately 89% of SJTC’s harvested logs were sold directly or indirectly to SSC and SJTC charged SSC the highest price that SSC paid for logs on the open market.

GIFT TAX VALUATION

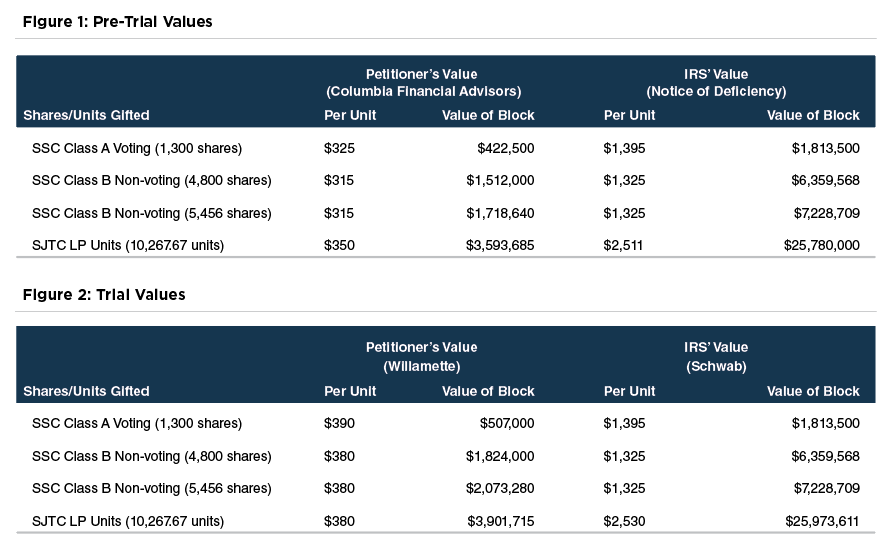

In May 2009, Mr. Jones formed seven family trusts and made gifts to those trusts of SSC voting and nonvoting stock. He also made gifts to his three daughters of SJTC limited partner interests. Mr. Jones filed a timely gift tax return reporting values based upon appraisals prepared by Columbia Financial Advisors as shown in Figure 1 on the next page (Petitioner’s Value). The IRS notice of deficiency asserted values much higher.

A petition was filed in the Tax Court by Mr. Jones in November 2013. Mr. Jones died in September 2014 and was replaced in the Tax Court proceeding by his estate and personal representatives. His estate then engaged another appraiser, Robert Reilly of Willamette Management Associates. Mr. Reilly was noted by the Court to have “performed approximately 100 business valuations of sawmills and timber product companies.”

The original appraiser for the IRS was not noted in the case decision. At trial, the IRS’ valuation expert was Phillip Schwab who, per the Court, has “performed several privately held business valuations.” Additionally, the IRS was noted as having “previously reviewed and completed several business valuations, including several sawmills.”

Their conclusions are presented in Figure 2.

SUMMARY OF THE COURT’S DECISION

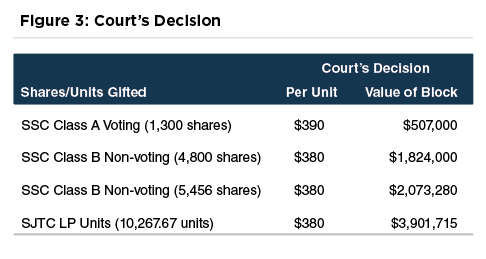

Ultimately, the Court sided with Mr. Reilly’s conclusions of values for SSC and SJTC, along with his reported discount for lack of marketability (DLOM). The only distinction the Court made with Mr. Reilly’s DLOM was to correct a typo wherein the Appendix in Mr. Reilly’s report referred to a 30% DLOM, when in actuality, he had applied a 35% DLOM. A summary of the Court’s conclusions are shown in Figure 3.

Item 1: SJTC’s Valuation Treatment as an Asset Holding Company or an Operating Company

The most critical issue surrounding the large difference in the valuation conclusions of SJTC for both experts centered on the valuation approach. The Court noted that “when valuing an operating company that sells products or services to the public, the company’s income receives the most weight.” Contrarily, the Court noted “when valuing a holding or investment company, which receives most of its income from holding debt securities, or other property, the value of the company’s assets will receive the most weight.”

A question in this matter: is SJTC an Asset Holding Company or is it an Operating Company? Petitioners’ experts concluded that SJTC was an operating company and relied on an income approach utilizing projections from management. Conversely, one respondent’s experts concluded that SJTC is a natural resource holding company and relied on the asset approach utilizing real estate appraisal on the underlying timberlands.

One of the critical factors the Court relied upon in determining its conclusion of the nature of SJTC’s operations centered on the Company’s operating philosophy. SJTC relied on a practice called “sustained yield harvesting” which didn’t harvest trees until they were 50 to 55 years old. As such, SJTC limited the harvest to the growth of its tree farms, even if selling the land or harvesting all of the trees would be the most profitable in the short-term. As discussed earlier, Mr. Jones began purchasing the timberlands and formed SJTC to supply the lumber to SSC for its long-term operations.

The other argument the Court considered when determining how to treat SJTC was the limited partner units in question. Specifically, the subject blocks of limited partner units could not force the sale or liquidation of the underlying timberlands. Recall, SSC maintained the 10% general partner or controlling interest in SJTC and its focus remained on SSC’s continued operations as a sawmill company dependent on SJTC for supplying the majority of its lumber.

Based on these factors, the Court concluded that SSC and SJTC “were so closely aligned and interdependent” that SJTC had to be valued based on its ongoing relationship with SSC, and thus, an income-based approach is more appropriate to value SJTC than a net asset value method. With this distinction, SJTC was more comparable to an operating company and less comparable to a traditional Timber Investment Management Organization (TIMO), Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT), or other holding or investment company.

Item 2: Reliance of Revised Management Projections in Valuation of SJTC and Impact of Economic Conditions

Both of Petitioner’s experts relied on management projections in the underlying assumptions of their discounted cash flow (DCF) analyses to value SJTC. The original appraisal utilized management projections that were included in the prior annual report. For trial, Mr. Reilly utilized revised projections from April 2009 in his DCF analysis.

Respondent challenged the use of the revised projections, despite the fact that their own second expert, Mr. Schwab, also used the revised projections in his guideline publicly traded company method. He chose to average the revised projections with those from the most recent annual report.

The Court specifically noted the economic conditions at the date of valuation, highlighting the volatility during the recession years. As such, the Court determined the revised projections were the most current as of the date of valuation and included management’s opinion on the climate of their market and operations. The impact of the current economic conditions is also referenced by the Court in another key takeaway that we will discuss later.

Item 3: Tax-Affecting Earnings in the Valuations of SJTC

Mr. Reilly computed after-tax earnings based on a 38% combined proxy for federal and state taxes. He further computed the benefit of the dividend tax avoided by the partners of SJTC, by estimating a 22% premium based on a study of S Corporation acquisitions. Respondent argued that since SJTC is a partnership, the partners would not be liable for tax at the entity level and there is no evidence that SJTC would become a C corporation. Therefore, respondent argued that the entity level tax rate should be zero.

The Court concluded that Mr. Reilly’s tax-affecting “may not be exact, but is more complete and convincing than respondent’s zero tax rate.” The Court also noted that the contention from respondent on this tax-affecting issue seems to be more of a “fight between lawyers” as the criticism appeared more in trial briefs than in expert reports. In fact, respondent’s expert, Mr. Schwab, argued that tax-affecting was improper because SJTC is a natural resources holding company and therefore its “rate of return is closer to the property rates of return” rather than challenging the lack of an actual entity level tax.

Item 4: Market Approach for SJTC

The Court and respondent’s expert agreed with Mr. Reilly’s market approach for the valuation of SJTC. With little to no disagreement, the key takeaway here is on Mr. Reilly’s analysis. The Court detailed the analysis by mentioning that Mr. Reilly selected six guideline companies. The Court also cited the analysis and reasoning behind Mr. Reilly’s selection of pricing multiples slightly above the minimum indications of the guideline companies. Specifically, Mr. Reilly noted that SJTC’s revenue and profitability for the most recent twelve months before the valuation date were below those of the guideline companies. Thus, he accounted for these differences in financial fundamentals in his selection of the guideline pricing multiples.

Item 5: Intercompany Debt between SJTC and SSC

Respondent argued that Mr. Reilly erred by excluding the receivable held by SSC and the corresponding liability of SJTC. Further, respondent contended that Mr. Reilly’s treatment of SSC’s receivable from SJTC as an operating asset, rather than a non-operating asset, reduced the value of SSC under his income approach since a non-operating asset was not added to that value.

On this issue, the Court weaved in earlier themes regarding the symbiotic relationship of the two companies and also the present economic conditions on the date of valuation to make its conclusion. The Court agreed with Mr. Reilly that the intercompany debt could be removed as a clearing account based on the idea that both companies operate as “simply two pockets of the same pair of pants.” The Court rejected respondent’s theories that this treatment of intercompany debt was only to avoid a negative asset valuation of SJTC and to reduce the value of SSC by not including the receivable as a non-operating asset.

The Court referenced the relationship of the two companies and how the joint credit agreements of the two companies were secured by SJTC’s timberlands. The Court recognized that SSC could not have obtained separate third-party loans without the assistance of SJTC’s underlying timberlands as collateral. A further detail of the two companies’ relationship was revealed earlier in this decision. 2009 economic conditions also included subprime mortgage lending crises, particularly in the housing market. Around this time, SSC was anticipating a shift in the market from green lumber to dry lumber. Dry lumber production required SSC to build dry kilns and a boiler in a larger renewable energy plant project. Because of economic conditions, SSC was not able to obtain the construction loans to finance the renewable energy plant for itself or with another planned related entity. Instead, SSC was forced to borrow against the timberlands of SJTC.

Ultimately, the Court viewed the two companies (SSC and SJTC) as a single business enterprise and concluded that Mr. Reilly’s treatment of the intercompany debt captured their relationship.

Item 6: Valuation of SSC – Treatment of General Partner Interest in SJTC

Respondent’s criticisms of Mr. Reilly consisted of three items:

- The treatment of Intercompany debt between the two companies

- Tax-affecting earnings

- The treatment of SSC’s general partner interest. The Court handled the intercompany debt and tax-affecting treatment consistently with SJTC’s valuation

Mr. Reilly captured the value of SSC’s general partner interest in SJTC by projecting a portion of the expected partnership income in his projections. Specifically, Mr. Reilly projected $350,000 annually for SSC’s general partner interest based on an analysis of the 5-year and 10-year historical distributions from SJTC.

Respondent claimed that this approach undervalued SSC’s general partner interest by not considering its control over SJTC and treating it as a non-operating asset to be valued by the net asset value method.

The Court concluded that SSC’s general partner interest in SJTC is an operating asset again citing the single business enterprise relationship between the two companies. Further, the value of SSC’s general partner interest is best estimated by the expected distributions that it would expect to receive.

Item 7: Buy-Sell Agreement Items

Although not directly discussed and cited in any of the Court’s factors that we have discussed so far, the decision did highlight certain elements from SSC’s and SJTC’s buy-sell agreements as we noted. Both buy-sell agreements contained language that prohibited the sale of the entity or transfers within the units/shares that would jeopardize the current tax status of the Companies as an S Corporation (SSC) and Limited Partnership (SJTC), respectively. Both agreements called for discounts for lack of control, lack of marketability, and lack of voting rights of an assignee (where applicable) to be considered. Finally, both agreements stated that the valuations of the entities should consider the anticipated cash distributions allocable to the units/shares.

CONCLUSIONS

While the Court’s decision to allow the tax-affecting of earnings (like in the Kress case) in the valuations of SSC and SJTC will dominate the headlines, there are additional takeaways from the case that impact the valuations. Of note, the disparity in experience of the appraisers involved, consideration of the current economic conditions, and the purpose and nature of the business relationship of the two companies seemed to influence the Court’s conclusions. Finally, the distinction and eventual valuation treatment of SJTC as an operating company rather than a holding company was of particular interest to us.