Richmond v. Commissioner

In Richmond v. Commissioner (Estate of Helen P. Richmond, Deceased, Amanda Zerbey, Executrix, Petitioner v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. T.C. Memo. 2014-26), several key issues were addressed including:

- A split is highlighted among different Courts of Appeals and the Tax Court regarding how the implicit tax liability for a built-in capital gain (“BICG”) should be handled in a business valuation. The tax can be deferred. According to the Tax Court, a prospective BICG tax liability is not the same as a debt that really does immediately reduce the value of a company dollar for dollar.

- The Tax Court rejected the income approach to valuation for this asset-holding entity. It clearly stated that the Net Asset Value approach is consistent with the precedent of using net asset valuations for companies with asset holdings whose underlying values are readily ascertainable.

- The Tax Court assessed substantial penalties.The reported value on the estate tax return was less than 65% of the proper value, thereby triggering the benchmark for a “substantial” understatement under the tax law.

Background

At the time of her death, Helen Richmond held a 23.44% interest in a family-owned personal holding company, Pearson Holding Company (“PHC”). PHC was incorporated in Delaware in 1928 as a family-owned investment holding company, a Chapter C corporation. At the valuation date, PHC held a portfolio with an asset value of $52,159,430 and liabilities of only $45,389. Accordingly, PHC had a net asset value of $52,114,041. PHC’s portfolio of assets consisted of government bonds and notes, preferred and common stocks, cash, receivables and a modest security deposit. Common stocks represented over 97% of the total portfolio. Due to a low turnover in the underlying securities, PHC had an unrealized gain approximating $45,576,677, or 87.5% of the net asset value.

The co-executors of the estate engaged a law firm to prepare the estate tax return and retained a CPA at an accounting firm to value the PHC stock for purposes of the estate tax return. The estate tax Form 706 was filed timely. The Court noted that the CPA had a Master of Science in taxation, experience in public accounting involving audits, management advisory, litigation support and tax planning, was a member of the AICPA and other accounting groups, and had appraisal experience having written 10-20 valuation reports and testifying in court, but he did not have any appraiser certifications. The CPA prepared a draft report that valued the decedent’s interest at $3,149,767, using a capitalization of dividends method. Without further consultation with the CPA, the estate filed Form 706 based on this report. The IRS issued a statutory notice of deficiency. The IRS determined a value of the estate’s interest at $9,223,658. The tax liability was thereby increased, and a gross valuation misstatement penalty of $1,141,892 was determined.

At Trial

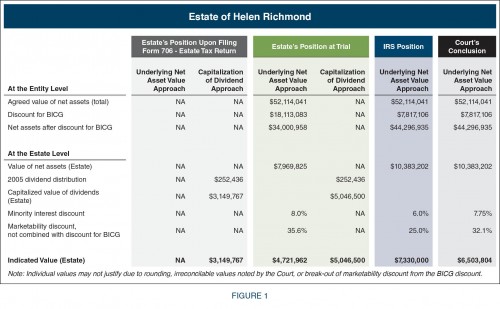

For ease of comparison, the position and conclusion of all parties at trial is shown in Figure 1.

At trial, the IRS expert in business valuation used a discounted net asset value approach (NAV). The agreed value of net assets, $52,114,041, was discounted by $7,817,106 before allocating the net value to the Estate’s 23.44% interest. The $7,817,106 represents 15.0% of the net asset value, and 43.16% of the agreed capital gain tax liability of $18,113,083, and 17.15% of the approximate unrealized gain of $45,576,677. The Court’s opinion described a convoluted rationale for the 15% BICG discount stating its “reasoning is not supported by the evidence.” The IRS expert further applied a 6% minority interest discount and a 25% marketability discount, concluding the Estate’s interest at $7,330,000. The Court noted this value was lower than the $9,223,658 value stated in the IRS’s initial notice of deficiency.

The original information on Form 706 was not defended at trial. Rather, the Estate offered a second opinion prepared by a business valuation expert, requesting that the Court adopt this expert’s opinion. This expert provided opinions based on both the underlying net asset value approach and the capitalization of dividends approach. The underlying net asset value approach discounted the UNAV by 100% of the BICG ($18,113,083), and then took an 8% minority interest discount and a 35.6% marketability discount. The Estate’s interest was $4,721,962 by this approach. This expert also offered an opinion based on the capitalization of dividends approach, incorporating the concepts of minority interest and marketability into the capitalization rate. The capitalization of dividends approach to value determined the Estate’s interest at $5,046,500.

In its opinion, the Court concluded that only the net asset value approach was appropriate for this asset holding entity. The opinion states that the agreed net asset value should be discounted by the 15% suggested by the IRS expert ($7,817,106), further discounted by 7.75% for the minority interest discount and 31.2% for a marketability discount. A value for the Estate at $6,503,804 was established by the Court.

The Court determined its 7.75% minority discount by referencing 59 closed-end funds utilized by both the IRS and Estate experts. Although the IRS was at 6% and the Estate at 8%, the Court examined the data presented and removed three outliers they believed skewed the mean, and re-calculated the mean at 7.75%. The Court concluded this to be reasonable.

The Court determined its 32.1% discount for lack of marketability by referencing restricted stock studies provided by both the IRS and the Estate. Both experts had interpreted those studies for their own purposes and the Court stated that, based on the studies, a general agreement appeared to exist that a marketability discount in the range of 26.4% to 35.6% with an average discount of 32.1% was appropriate and concluded to be reasonable.

Here’s What’s Important

The Court made it clear the NAV approach is more appropriate for an asset-holding entity as opposed to a capitalization of dividends approach. The capitalization of dividends valuation method is based entirely upon estimates about the future – the future of the general economy, the future performance of the Company and its future dividend payouts, and even small variations in those estimates can have a substantial effect on the value. The NAV approach does begin by standing on firm ground – publicly traded stock values that one can simply look up.

With regard to the BICG tax liability, the Court found that, despite contrary decisions by some courts, a discount of 100% of the implicit tax liability would be unreasonable, because it would not reflect the economic realities of the Company’s situation. The Court concluded the BICG tax liability cannot be disregarded in valuing PHC, but that PHC’s value cannot be reasonably discounted by this liability dollar for dollar. The Court concluded that the most reasonable discount is the present value of the cost of paying off that implicit liability in the future, and calculated the present value of that $18.1 million BICG liability over a 20 to 30 year holding period at discount rates ranging from 7.0% to 10.27%. It found the $7.8 million discount suggested by the IRS fell comfortably within their calculated range, thereby confirming that discount as reasonable in this case.

The Court assessed an accuracy-related penalty against the Estate. The Estate initially reported the value at $3,149,767 on Form 706, versus the Court’s determination of $6,503,804. The estate tax return was less than 65% of the proper value and a substantial valuation understatement exists under IRS guidelines. However, the 20% penalty would not apply to any portion of an underpayment if it is shown there was a reasonable cause for such portion and the taxpayer acted in good faith with respect to such portion. But the Court could not say in this case that the Estate acted with reasonable cause and in good faith by using an unsigned draft report as its basis for filing Form 706. Substitute appraisals were used at trial, and the value on the Estate Tax Return was left essentially unexplained. Additionally, while the initial value was prepared by a CPA, he was not a certified appraiser. The Court stated: “In order to be able to invoke ‘reasonable cause’ in a case of this difficulty and magnitude, the estate needed to have the decedent’s interest in PHC appraised by a certified appraiser. It did not.” The Court sustained the Commissioner’s imposition of an accuracy-related penalty.

The Tax Court has wrestled with the controversy of the appropriate treatment of the implicit tax liability for the built-in gain in a C-corporation since the repeal of the General Utilities doctrine by the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The taxpayer’s expert took 100% of the stipulated implicit tax liability as a discount against net asset value in the Richmond case. But the Tax Court countered by acknowledging conflicting opinions on this issue and stating “However, other Courts of Appeals and this Court have not followed this 100% discount approach, and we consider it plainly wrong in a case like the present one.”

The Tax Court resolved the issue in Richmond by discounting to present value the amortization of the current implicit tax liability over a period of 20 to 30 years. However, that methodology may not stand the test of an effective challenge. Such an approach fails to consider prospective underlying growth of the corporate “inside assets” in question. As those assets grow in the future based upon some reasonably achievable or projected growth rate, the implicit tax liability will grow right along with them since the underlying tax basis will remain fixed until the assets are sold. This expanding “spread” between the assets’ fixed tax basis and their future fair market value enhances the implicit tax liability beyond the known amount at a given valuation date. That growing liability will serve to diminish investment returns and would be considered in any fair market value negotiation for C-corporation stock at the valuation date.

The Business Appraisers’ Position

Mercer Capital addressed the investment rate of return perspective for hypothetical buyers and sellers dealing with built-in gains in our article: Embedded Capital Gains in Post-1986 C Corporation Asset Holding Companies. Chris Mercer concluded the analysis by stating: The end result of this analysis is that there is not a single alternative in which rational buyers (i.e., hypothetical willing buyers) of appreciated properties in C corporations can reasonably be expected to negotiate for anything less than a full recognition of any embedded tax liability associated with the properties in the purchase price of the shares of those corporations. And rational sellers (i.e., hypothetical willing sellers) cannot reasonably expect to negotiate a more favorable treatment, because any non-recognition of embedded tax liabilities by a buyer translates directly into an avoidable cost or into lower expected returns than are otherwise available. Valuation and negotiating symmetry call for a full recognition of embedded tax liabilities by both buyers and sellers.” View the full article here.