Specialty Finance M&A

October was another sour month for bank investors. The KBW Nasdaq Regional Bank Index declined 6.5% through October 27 and is down 27.9% year-to-date. While the failure of SVB and Signature Bank in March caused bank stocks to nosedive into the end of the first quarter, the ~100bps lift in the yield in the 10-year UST note produced a similar result during September and October.

Not surprisingly, bank M&A activity remains muted, punctuated by an occasional transaction of note such as Evansville-based Old National Bancorp (NYSE: ONB) and Nashville-based CapStar Financial Holdings, Inc. (NASDAQ: CSTR) agreeing to merge in a stock-swap that valued CapStar at $346 million.

Acquirers’ shares trade at low multiples, and fair value marks of low-rate, fixed-rate assets are draconian. Plus, there is the capital “question” given an extended benign credit cycle and the gap between regulatory capital and core equity capital that is marked for unrealized bond losses. Nonetheless, the best deals (and loans) often are made during challenging times.

Like conventional bank deals, transaction volume for specialty finance companies is modest compared to recent years. More so than in recent years, activity can be described as tuck-in deals to introduce or augment a product offering, or opportunistic for distressed sales. Generally, bank acquirers have favored commercial finance over consumer finance lenders given challenging consumer compliance associated with auto finance and highly cyclical nature of mortgage banking.

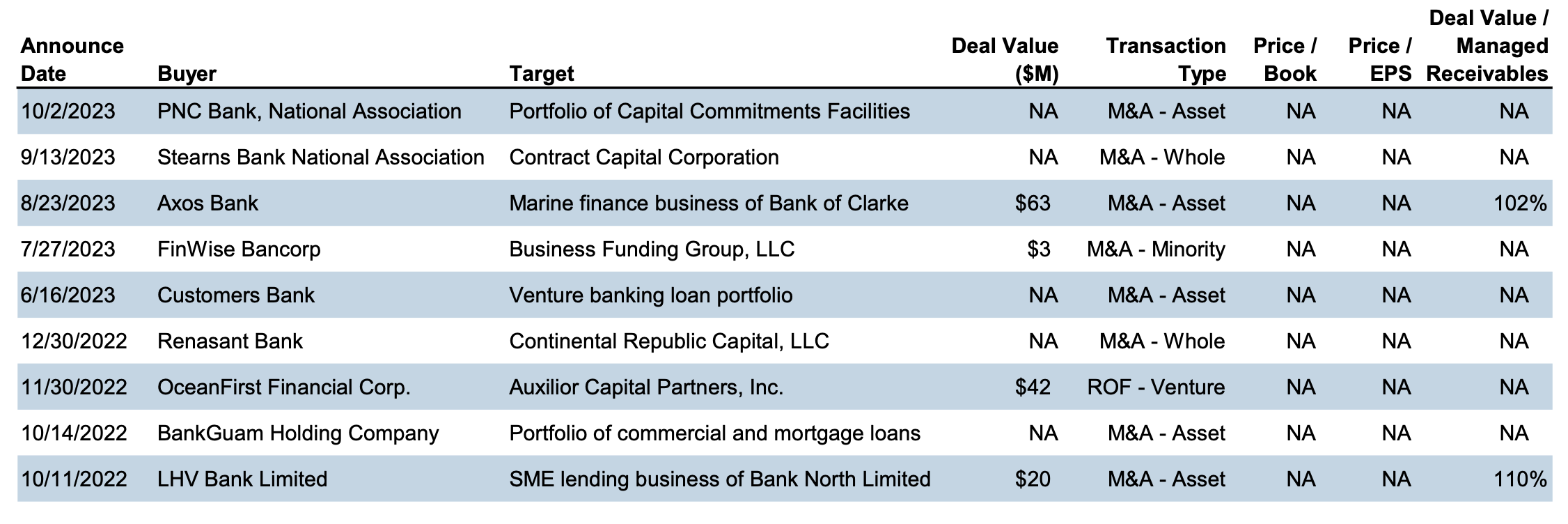

As shown in the table below, there have been only five specialty finance deals involving a bank buyer announced since the beginning of the year compared to 13 in 2022 when rising rates sidetracked deal activity during the second half of the year. Prior to 2022 excluding 2020, a typical year would entail banks acquiring 20+ specialty finance companies per year according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Click here to enlarge the table above

One of the more innovative transactions was a white label deal Synovus struck with Cincinnati-based Verdant Commercial Capital in July 2022 whereby Verdant will serve as the white label originator of equipment leases for Synovus Equipment Leasing. Synovus now offers equipment leasing of $25 thousand to $50 million to its clients through Verdant, which has expertise and execution capabilities that Synovus does not have. Synovus also provides lender finance to Verdant via a credit facility.

While the deal making environment is challenging, specialty finance acquisitions can be accretive to shareholders if structured and priced properly. Generally, the benefits we see are:

- High return on capital assuming the buyer does not overpay given the high(ish) yields most specialty finance companies produce when combined with low-cost bank deposit funding;

- Portfolio diversification, including a reduction in CRE exposure that is an issue with many banks;

- Cross sell opportunities, including establishing a deposit relationship; and

- Valuation arbitrage in which specialty companies often are valued at P/E multiples of 6-9x compared to 9-13x for commercial banks.

No acquisition comes without a unique set of risks. The following are some of the cons to a specialty finance acquisition:

- Credit risk in that specialty finance lender borrowers may be less well capitalized and more downturn sensitive than the “average” commercial bank customer with collateral often consisting of movable collateral vs real estate;

- Credit box risk in that executive bank management tightens the credit box too much and thereby weakens the business case for owning in the first place;

- Enterprise risk related to different processing and monitoring systems that may not be as robust as a bank’s;

- Integration risk due to cultural differences though this can be lessened to the extent the specialty finance company remains a separate subsidiary or division;

- Funding may be an issue if bank ownership tightens too much and thereby puts the unit at a competitive disadvantage.

Acquiring a specialty finance company comes with a unique set of hurdles, different than acquiring a bank. Cost synergies other than cost of funds usually are inconsequential. Buyers need to be aware of the target’s ownership structure and ensure that remaining managers (or key employees) upon close of the transaction are financially aligned with the bank’s goals.

While bank buyers should focus on the impact to capital, dilution to tangible BVPS and how quickly the dilution is recovered via EPS accretion, heavy consideration should be placed on the return on invested capital.

While the Street likes to focus on internal rate of return calculations in which much of the IRR is predicated upon a terminal value derived from a multiple of earnings, we think a simpler approach is how much money can the unit make compared to the capital outlay that encompasses all deal costs. If the return is sufficiently high, other metrics should be okay.

As for structuring a transaction, cash vs stock and how much consideration should be reserved for an earn-out are standard questions. The higher rate environment today makes each financing option more expensive in the form of shares that might be issued trade at modest multiples, while the cost of debt and opportunity cost of excess liquidity are high compared to several years ago.

Nonetheless, the more challenging operating environment for banks and non-bank lenders may lead to more attractive acquisition opportunities for banks with the capacity to engage in a transaction.