Sub-Chapter S Election for Banks

An S “election” represents a change in a bank’s tax status. When a bank “elects” S corporation status, it opts to become taxed under Subchapter S of the U.S. Tax Code, instead of Subchapter C of the Code. When taxed as a C corporation, the bank pays federal income taxes on its taxable income. By making the S election, the bank no longer pays federal income tax itself. The tax liability does not disappear altogether, though. Instead, the tax liability “passes through” to the shareholders. This means that the bank’s tax liability becomes the obligation of the bank’s shareholders. While no guarantees generally exist, the bank will ordinarily intend to distribute enough cash to the shareholders to enable them to satisfy the tax liability.

An Example

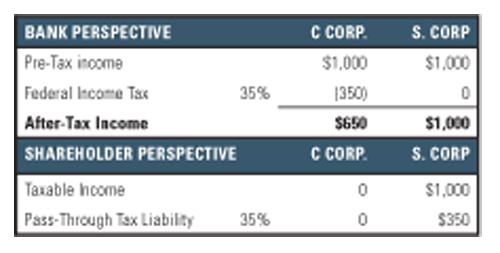

The following table shows what happens when a bank makes an S election. In the table, the bank no longer incurs any federal tax liability following the S election. However, the $350 tax obligation simply “passes through” to the shareholders.

S Election Benefits

In the preceding table, the bank’s pre-tax income generated a $350 tax obligation, regardless of whether the bank was taxed as a C or S corporation. In the C corporation scenario, the bank directly paid the tax obligation to the government; in the S corporation alternative, the shareholders paid the taxes due on the bank’s earnings. Since the taxes due remain constant at $350 regardless of whether the bank elects

S corporation status or not, what incentive exists for banks to elect S corporation status?

The S election creates two primary tax advantages relative to C corporations:

- Dividends paid by a C corporation are taxable to the shareholders. However, shareholders in an S corporation incur no tax liability beyond the taxes on their pro rata share of the S corporation’s taxable income.

- In a C corporation, a shareholder’s tax basis generally remains constant during the period the shareholder holds the investment. S corporation shareholders, however, benefit because their tax basis increases to the extent that the bank retains earnings. This may reduce the capital gains taxes payable when a shareholder sells any shares of the bank’s stock.

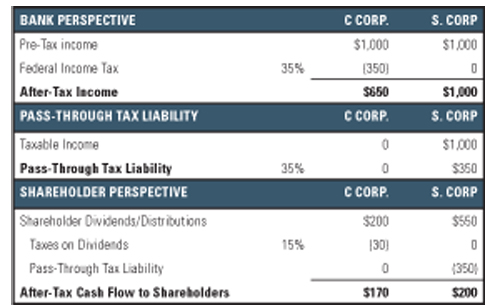

The best way to illustrate tax advantage #1 is with an example.

In the C corporation scenario, the bank pays $200 of dividends to shareholders. After the shareholders pay taxes on these dividends (at a 15% tax rate on dividends), the shareholders will have after-tax cash flow of $170 from their investment. Assume, instead, that the bank elects S corporation status. In this case, the shareholders owe taxes of $350 (35% of the bank’s $1,000 pre-tax income), but the bank makes distributions of $550. This leaves the shareholders with $200 of after-tax cash flow. No further taxes are owed on the $200. In fact, for any amount of distributions between zero and $1,000 (the bank’s pre-tax earnings), the shareholders will generally face tax liability of $350. By electing S corporation status, therefore, shareholders increase their after-tax cash flow from $170 to $200, an 18% increase.

Disadvantages of an S Election

Given the aforementioned tax benefits, why would every bank not elect S corporation status? Several potential disadvantages of the election exist:

- Limitations exist on the type and number of shareholders that may hold stock in an S corporation. If the bank currently has too many shareholders, a transaction that “squeezes out” certain shareholders may be necessary in order to make the election. This gives rise to the risk that shareholders can sue, demanding a greater amount for their shares than offered by the bank.

- S elections can increase the risk associated with an investment in the bank. For instance, assume that the bank reports a pre-tax loss of $1,000. If the bank is taxed as a C corporation, it will generally record a tax benefit related to the loss, and, the bank’s retained earnings will fall by only $650 (the $1,000 pre-tax loss minus a $350 tax benefit, assuming a 35% tax rate). However, if the bank is taxed as an S corporation, it will record no tax benefit in its books, and the entire $1,000 pre-tax loss will flow through retained earnings. Thus, in the event a loss occurs, the S corporation’s capital account will be $350 less than the capital account of a similarly situated C corporation (which is equal to the amount of the tax benefit recorded by the C corporation). In the event that the losses are material to the bank, the adverse capital treatment of an S corporation can prove material.In addition to the preceding effect on capital, it is entirely possible for the S corporation bank to have taxable income (thereby creating a tax obligation on the part of the bank’s shareholders) but a net loss for book purposes. This could occur because, for instance, loan loss provisions in excess of actual loan losses may not be tax deductible. This situation could create a highly negative outcome for the bank’s shareholders – the shareholders may face a personal tax liability but the bank’s capital position may limit its ability to make distributions to the shareholders.

To minimize these risks, the board of directors and management may adopt a more conservative management style for the S corporation bank than the C corporation bank. For instance, higher capital ratios may be desirable. In addition, the bank may adopt more strict underwriting requirements or maintain a lower loan/deposit ratio to reduce the risk of losses.

- The advantages of S elections depend to some degree on the relationship between corporate, personal, and dividend tax rates. In the future, changes in the relationship between these tax rates could make S elections less desirable. For instance, a reduction in the C corporation tax rate, while the personal tax rate increases, could reduce or eliminate the benefits associated with an S election.

- Certain one-time costs associated with an S election exist. For example, a bank must generally write-off its deferred tax asset upon the S election. This write-off will reduce earnings and capital in the year it occurs.

- The bank may still face federal income taxes on certain assets sold within ten years of the S election. This is referred to as the “built-in gains” tax.

Conclusion

S corporation elections may be an attractive alternative for banks, but a careful examination of the advantages and disadvantages is necessary. Banks with relatively low balance sheet growth and high profitability often make the best candidates for S elections, because these banks have the capacity to distribute a large portion of their earnings. On the other hand, an S election would be less beneficial for other types of banks. For instance, banks that intend to pursue acquisitions or that have potentially volatile earnings may be better served by remaining C corporations.

If your bank does elect to make an S election, it is typically more complicated than simply “checking a box” on a tax filing. Instead, a number of professionals may need to be involved to ensure the bank’s goals are achieved:

- The bank’s corporate attorney would be involved throughout the process. The attorney would assist in handling any shareholders that do not qualify as S corporation shareholders (such as negotiating a voluntary repurchase or structuring an involuntary transaction), drafting any necessary proxy statements distributed to the shareholders, and creating the shareholder agreement that restricts the sale of the bank’s shares to preserve the S election.

- The bank’s tax accountant or tax attorney would also have an important role. This includes analyzing the shareholder base to determine which shareholders may not qualify as S corporation shareholders and considering any specific tax issues relevant to a particular bank.

- A business appraiser has several roles. First, the bank may require an appraisal of its stock prior to the S election for purposes of the built-in gains tax that may arise if the bank is eventually sold. Second, appraisals are often necessary when repurchasing stock from non-qualifying shareholders, whether the transaction is voluntary or involuntary. Third, a fairness opinion may be needed to determine the fairness to the bank’s shareholders or one specific group of shareholders such as the ESOP of the “squeeze out” transaction.

Reprinted from Mercer Capital’s Value Matters™ 2008-08, published August 31, 2008