This Interest Rate Environment Done Got Old

One of BankWatch’s favorite blues artists is Junior Kimbrough. In “Done Got Old,” Junior sings:

Well, I done got old

Well, I done got old

I cain’t do the thangs I used to do1

You could say the same about this interest rate environment. Earlier in 2023, markets were expecting Fed rate cuts by late 2023; alas, this expectation missed the mark. Now though, as a higher-for-longer rate environment descends on the industry, perhaps banks cain’t do the thangs they used to do in a lower rate environment.

We had the good fortune to speak at Bank Director’s Bank Board Training Forum in Nashville earlier in September. Our presentation, Valuation Issues Post-SVB, focused on issues emerging from a higher-for-longer environment. Right on cue, the Wall Street Journal published an article entitled, “Higher Interest Rates Not Just for Longer, but Maybe Forever” arguing that the “neutral” interest rate that balances inflation and unemployment has risen.2

This article covers some implications of a higher-for-longer rate environment included in our conference presentation:

- Funding Costs and Net Interest Margins

- Growth & Capital Planning

- Securities Portfolio Management

- Credit Quality Risks

- Mergers & Acquisitions Impact

Funding Costs & Net Interest Margins

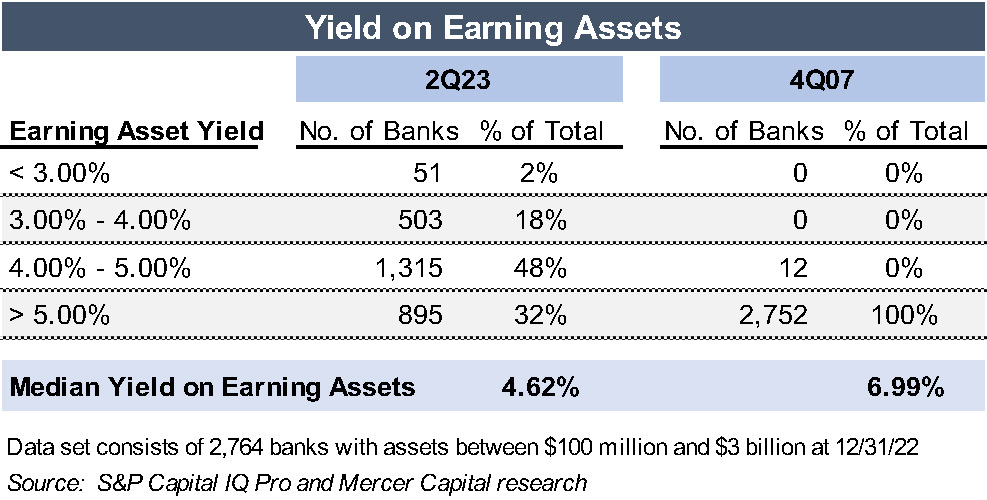

For many banks, a higher-for-longer rate environment is quite favorable, though sometimes media reports dwell on banks squeezed by rising rates. Figure 1 compares net interest margins between the first quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2023. We included the first quarter of 2022 as the impact of rising rates was minimal, PPP fee income had largely been recognized in prior quarters, and balance sheet composition reflected the changes that occurred during the pandemic. Our research indicates that 68% of the 2,764 banks included in the analysis reported a wider net interest margin in the second quarter of 2023. Many banks, in fact, face greater exposure to a long-term low rate environment than the current rate environment.

Figure 1

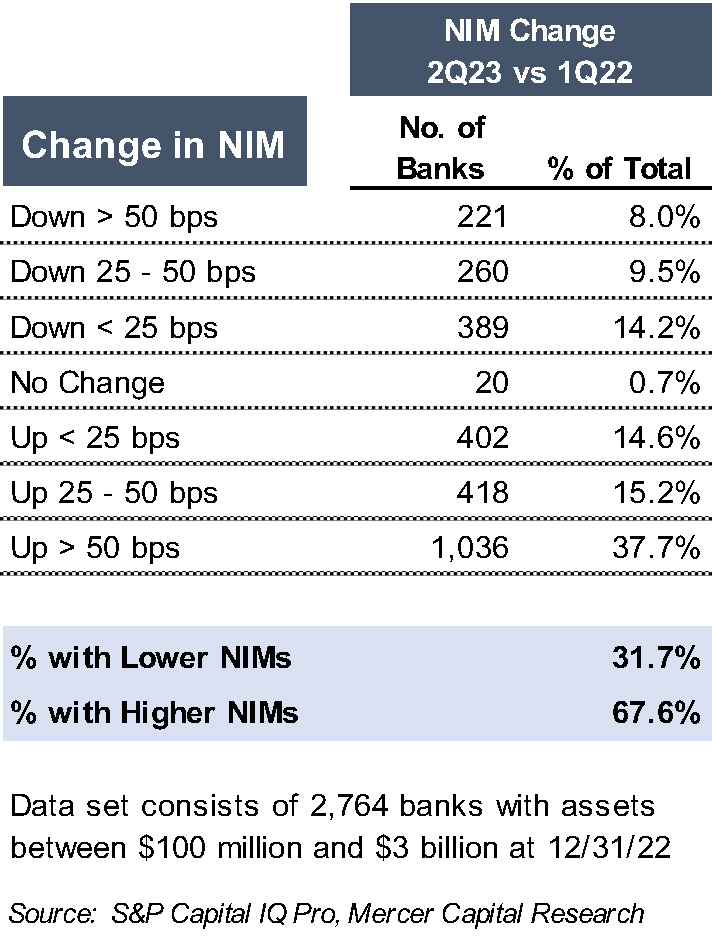

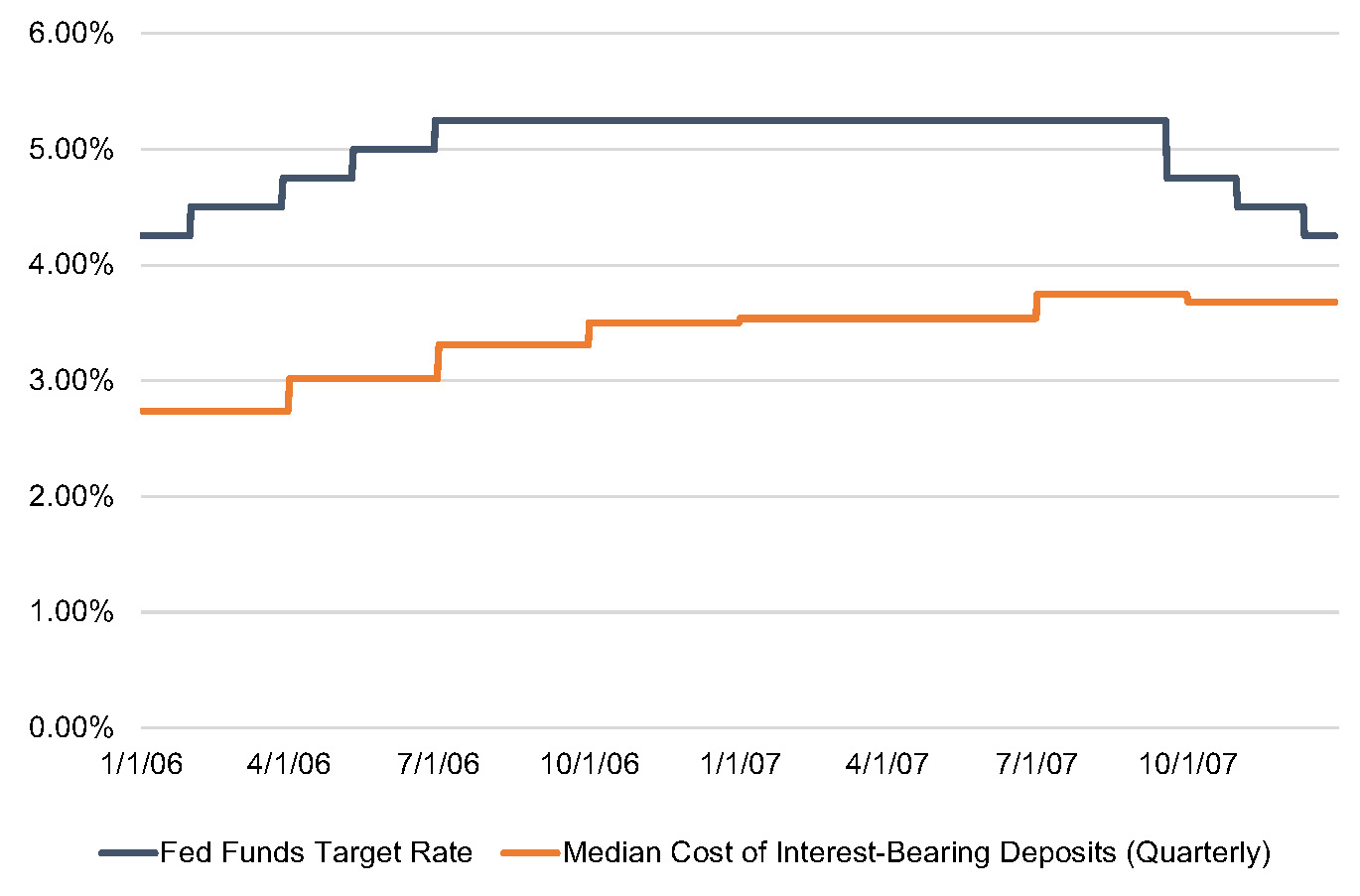

The most recent period in which the Fed Funds target rate exceeded 5% occurred from 2006 to 2007. As shown in Figure 2, the median cost of interest-bearing deposits for the same group of banks included in Figure 1 reached 3.75% in the third quarter of 2007. For the second quarter of 2023, however, this group’s cost of interest-bearing deposits was only 1.59% (see Figure 3).

Figure 2 :: 2006-2007 Cycle

Figure 3 :: 2022-2023

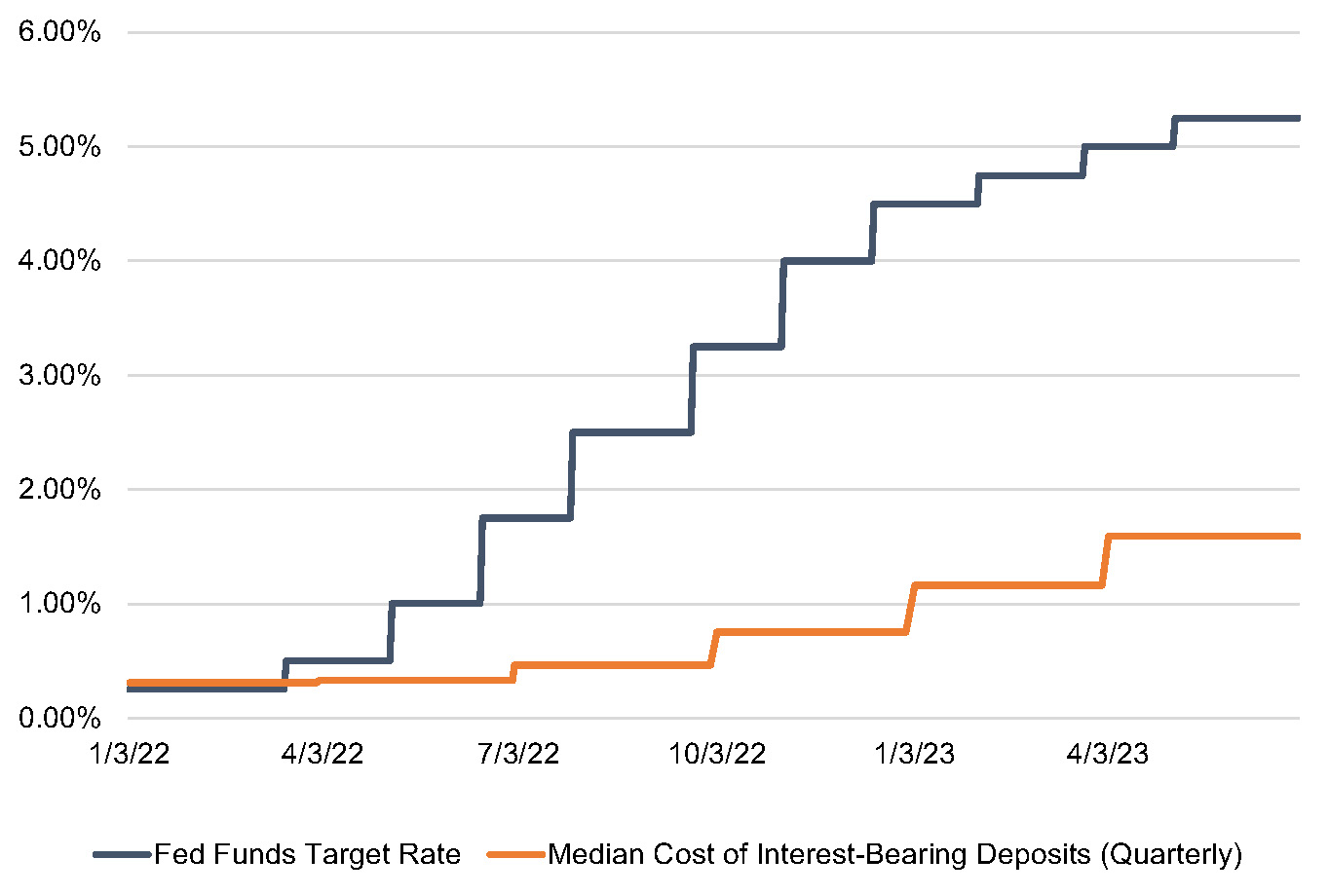

Deposit rates presumably will grind higher, and an extrapolation of recent deposit cost changes suggests that the median cost of interest-bearing deposits will reach 2.00% to 2.50% from 1.59% in the second quarter of 2023. Nevertheless, deposits cost for most banks likely will remain well below the level reported in 2006 and 2007. This is desirable for several reasons, but most importantly because earning asset yields are well below the level reported in 2006 and 2007. In the fourth quarter of 2007, the median yield on earning assets was 6.99%, which is 237 basis points higher than in the second quarter of 2023 (per Figure 4).

From an investment standpoint, current conditions somewhat mirror the late 1970s when most thrifts and some banks were caught with long(er) duration assets as funding costs rose. We believe the “asset duration issue” has weighed on bank stocks this year though institutional investors’ focus may now be shifting to credit risks.

Figure 4

Growth & Capital Planning

During periods marked by low rates, banks’ strategic plans often were oriented around loan growth, especially during the pandemic when banks were flush with deposits. This strategic direction, in turn, often was implemented by hiring loan officers or entering new markets. In a higher-for-longer rate environment, do these strategies remain appropriate?

A loan-oriented growth strategy certainly remains defensible for those banks that still hold substantial liquidity at the Federal Reserve. For other banks, though, the question becomes more complex. To measure the profitability of loan growth, banks should use their marginal cost of funds, not their current average cost of funds. Hiring an investor commercial real estate lender may be difficult to justify when the marginal cost of funding is 5%, as every loan originated by the new lender may compress the net interest margin. Other financial or strategic motivations could support such loan growth strategies—like obtaining long-term customer relationships or locking in an attractive loan yield supported by prepayment penalties–but bank directors should be aware of the return on capital implications of more aggressive loan growth.

During a higher-for-longer rate environment, balance sheet growth will be governed mostly by a bank’s ability to obtain funding at a reasonable cost. And we know that building core deposits takes time. Given these constraints, bank directors should temper their expectations regarding balance sheet growth. Individuals possessing strong deposit customer relationships or access to specific deposit niches will become more valuable traits in new hires (or more subject to poaching by other banks).

If the return on capital from more aggressive loan growth strategies is diminished in a higher-for-longer rate environment, what should banks do with internally-generated capital?

If the bank’s stock is trading at 8x to 10x earnings, share repurchases seem attractive (subject to one’s outlook regarding the probability of credit deterioration).

A more controversial strategy would entail using some excess capital to effectuate a partial restructuring of the bond portfolio. Rather than tying up capital with loans earning a relatively low spread over marginal funding costs, a bank could exit some low yielding investments at a loss that could be replaced with investments at current market rates (or used to pay down costly borrowings).

Banks could analyze which strategy produces a better return on capital. We will explore this issue in a future article, but suffice to say as the spread over marginal funding costs for new loans declines, enhancing earnings by “investing” some capital in a bond portfolio restructuring looks financially more appealing.

Issuers of subordinated debt may wish to accumulate funds to repay these instruments when the current rate resets after five years, rather than face an interest rate hundreds of basis points higher than the current fixed rate.

Securities Portfolio Management

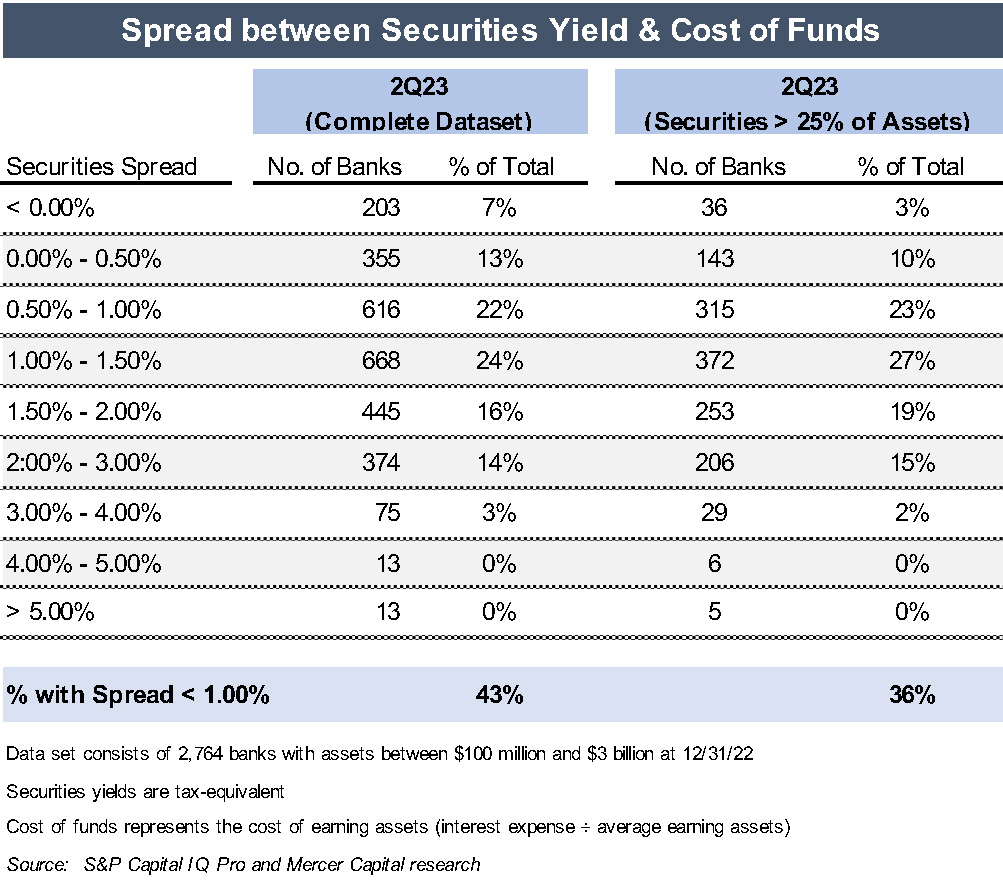

As rates linger at a higher level, more banks will experience a low or negative spread on their securities portfolios, which we measure as (a) the yield on securities minus (b) the cost of earning assets (interest expense divided by average earning assets). Figure 5 presents a stratification of banks’ securities spreads based on data for 2,764 banks with assets between $100 million and $3 billion.

The number of banks with low or negative securities portfolio spreads has steadily increased. The proportion of banks with spreads of less than 1% increased from 8% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 36% in the fourth quarter of 2022 to 43% in the second quarter of 2023. Similarly, banks with negative spreads increased from 2% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 3% in the fourth quarter of 2022 to 7% in the second quarter of 2023.

Figure 5

As hope diminishes that the unrealized securities losses will quickly reverse and the earnings drag from securities with low (or negative) spreads continues unabated, banks will face a reckoning. The currently unrealized losses will be recognized in one of two ways: immediately through sale of securities or over time through lower earnings. Choosing between those two options, whether consciously or not, becomes unavoidable in a higher-for-longer rate environment.

Credit Quality Risks

Credit quality has remained remarkedly strong, except for some sectors for which most community banks have limited exposure like lower credit score consumer lending and central business district office properties. Our research found that 61% of publicly traded banks with assets between $1 and $10 billion reported lower criticized loans (i.e., loans rated special mention or worse) at June 30, 2023 than at year-end 2022. Nevertheless, some issues may arise in a prolonged environment of higher rates:

- Vintage Migration. The risk of higher interest payments affecting borrower performance as repricing or maturing fixed rate loans adjust to current loan rates has been cited as a risk, albeit an unrealized one so far for most of our clients. However, a higher-for-longer rate environment means that more lower rate loans in banks’ portfolios eventually will be ensnared by higher rates. The 2020 and 2021 vintage originations, when loan rate competition was most aggressive, would be subject to the greatest payment shock upon maturity or repricing. A large portion of the 2020 and 2021 vintages will not begin repricing until at least 2024 or 2025—time will tell how these vintages perform with higher loan rates.

- Problem Asset Carrying Costs. During the Great Financial Crisis, the cost of carrying nonperforming assets—the foregone yield on nonaccrual loans or the interest cost associated with carrying other real estate owned—exacerbated loan loss provisions and OREO write-downs. The erosion of operating income as nonperforming assets increased often tipped banks into a position of needing to raise capital (or worse). However, these carrying costs occurred in a low rate environment.

In a high rate environment, these costs would be amplified. OREO of $1 million may have incurred an interest charge of $10,000 during the Great Financial Crisis; now that charge could be $50,000. Stated differently, it would require fewer nonperforming assets in the current rate environment to produce the same erosion of earning power as experienced in the Great Financial Crisis. - Cap Rates. CBRE’s quarterly commercial real estate cap rate study indicates that cap rates, while rising from 2021 levels, are not much different from levels reported between 2012 and 2019.3 This implies, of course, a tighter spread between cap rates and 10-year Treasuries. A higher-for-longer rate environment, particularly if the 10-year Treasury continues its recent rising trend, portends higher cap rates that could pressure valuations for commercial real estate properties serving as loan collateral.

- Capital Augmentation through Securities Sales. In the Great Financial Crisis, banks had a sort of “Fed put” where falling rates created gains on securities, which in turn plugged capital holes created by credit losses. That cushion protecting banks from dilutive capital raises or forced M&A transactions is unlikely to exist, even if rates decline to some extent from current levels given the low coupons on bonds purchased in 2020 and 2021.

Mergers & Acquisitions Impact

Bank M&A activity improved in August 2023, although from a low base in prior months. Several factors likely prompted this, including more visibility into the extent of deposit attrition and the trend in deposit interest rates. Additionally, the balance sheet marks that are necessary to complete a transaction are becoming more accepted by both buyers and sellers.

Beyond credit, several other considerations exist for M&A transactions in a higher-for-longer rate environment:

- Deposit due diligence. Due diligence in the past often has focused on credit risk and compliance. The current environment suggests a greater need for diligence around the deposit portfolio, such as regarding accounts with larger balances, accounts held by larger shareholders, and the volatility in balances over different periods.

A merger and the related conversion process often trigger customers to reassess long-term relationships. A buyer should assess the sensitivity of the deal valuation to deposit attrition that differs from the target’s historical norm. In low rate environments, an unexpected loss of deposits usually could be replaced by wholesale borrowings without materially affecting anticipated earnings. In a higher rate environment, though, this cushion does not exist. The unexpected attrition of low cost deposits could materially erode the target’s expected earnings contribution, given the current variance between core deposit and wholesale funding costs.

- Merging banks with divergent deposit costs, particularly if the target’s deposit costs exceed the buyer’s deposit rates. Will the market penalize the buyer for a transaction that materially increases the buyer’s cost of funds? If the buyer attempts to migrate the target’s (higher) deposit rates to the buyer’s (lower) deposit rate structure, the buyer risks losing deposits and facing the need to replace them with even costlier wholesale funds. If the buyer leaves the target’s deposit rates alone, though, will it cannibalize its own deposits? That is, will the buyer’s existing low cost deposits migrate to the higher rates offered to the target’s depositors? This risk may be easier to manage in out-of-market transactions than in-market transactions.

Conclusion

As indicated in Figure 1 at the beginning of this article, many banks continue to perform quite well in this rate environment despite occasional expressions of doom in some media reports. Hopefully, not too many banks will be singing the blues like Junior Kimbrough as this high rate environment persists.