2022 Credit Market Outlook for Family Businesses

In this week’s Family Business Director, we feature Jeff K. Davis, CFA, Managing Director of Mercer Capital’s Financial Institutions Group, a veteran banking analyst, and an editorial contributor to SNL Financial. He regularly is featured in American Banker, Bloomberg News, and other industry outlets.

Barring a change in the economic backdrop, the availability of debt financing for most family businesses in 2022 should be good; however, the cost of borrowing probably will rise in 2022. Market participants are highly certain the Fed will raise short-term policy rates to address high inflation that massive growth in monetary aggregates since March 2020 unleashed on financial markets initially and now the broader economy.

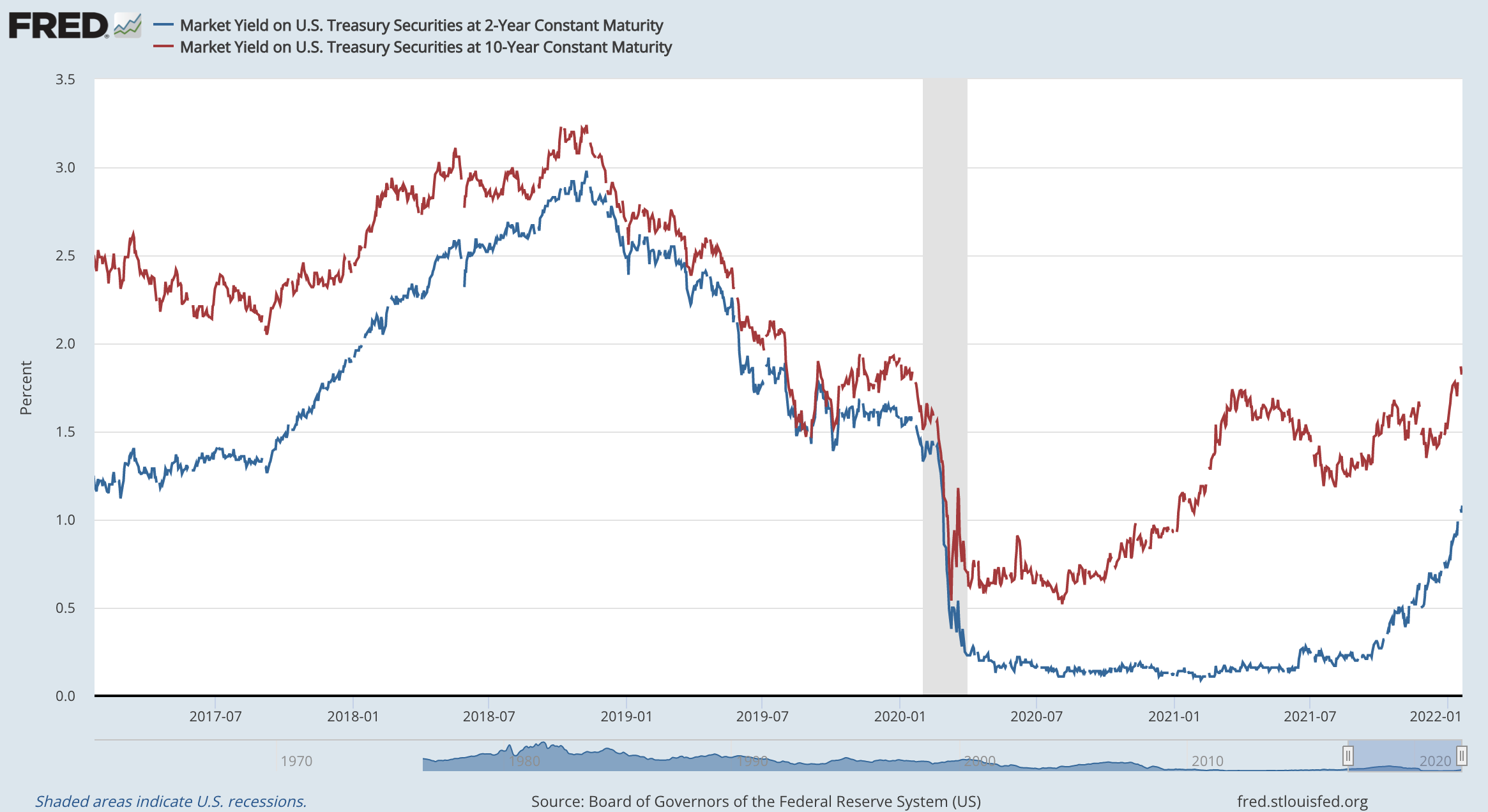

As shown in the chart below, the yield on two-year and ten-year US Treasury (“UST”) notes have been trending higher for some time. The two-year note is sensitive to short-term policy rates the Fed sets (e.g., the rate the Fed pays banks for reserves that are deposited with it). It has rapidly increased in yield (i.e., the price has declined) since last September when it became obvious that inflation was not “transitory” and the Fed faced a political as well as economic issue of having not acting sooner. Click here to expand the chart below.

Source: Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 2-Year Constant Maturity (DGS2) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

The yield on the 10-year UST is not directly tied to where the Fed sets short-term policy rates. Theoretically, the rate reflects economic growth expectations, inflation, and a term premium for long lending. If short-term policy rates are kept too low, then all else equals the yield on the 10-year would be expected to increase as growth and inflation expectations rise. Conversely, once the Fed starts hiking, long-term UST rates initially tend to rise less than the Fed hikes and later often decline as investors wager the Fed will hike until something breaks.

This is what occurred in 2018. The yield peaked in October and fell sharply as investors concluded the anticipated December rate hike would be ill-advised. The yield on the 10-year continued to trend lower in the first half of 2019 before the Fed was forced to reduce short-term policy rates three times to about 1.50% during the third quarter.

Since late March 2020, short-term policy rates have been near zero when the Fed cut rates to address illiquidity in markets and the economic shock from policy actions taken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

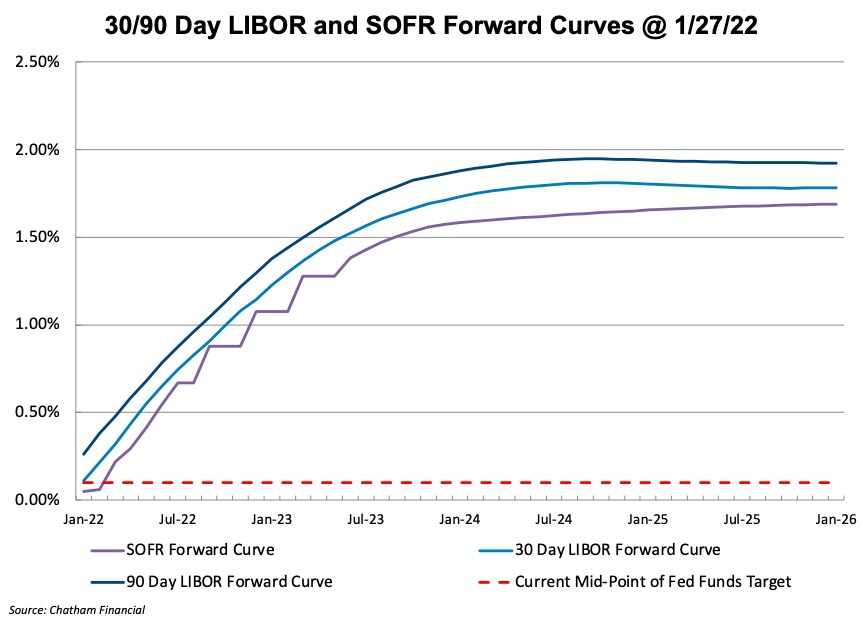

It is these short-term policy rates that are now poised to increase, which in turn impact short-term benchmark rates banks and other lenders use as a base rate to charge businesses, most notably 30-day and 90-day LIBOR and now the secured overnight funding rate (“SOFR”) for floating rate borrowings. (Note: LBIOR is in the process of being phased out and will be replaced by SOFR, AMERIBOR, and other less well-known overnight borrowing rates.)

Even with rising rates, competition will likely remain intense and preclude much if any increase in the margin over the base rate in 2022.

Fixed borrowing rates that track UST and swap rates for various maturities have already begun to rise somewhat and will increase further in 2022 provided UST yields continue to track higher.

Competition among lenders determines the margin over the base rate whether short-term floating or intermediate-term fixed the borrower will be charged. Even with rising rates, competition will likely remain intense and preclude much if any increase in the margin over the base rate in 2022.

As shown below, market participants are pricing in about four 25bps hikes in short-term policy rates by the Fed given about 100bps of increase in 30/90-day LIBOR based upon rates that are observed in the highly liquid Eurodollar market. Likewise, the forward SOFR curve also is pricing in about 100bps of increase over the next year. Over the next two years, the market is pricing in about 175bps of hikes, which would equate to seven 25bps hikes by the Fed compared to nine during the last hiking cycle that ended in December 2018.

If market expectations are fully realized, borrowing rates for family businesses should remain very low by historical standards, just not as low as 2020 and 2021. Our sense is that most businesses will not be materially impacted given the market projects’ low terminal rate. Higher rates will only be an issue if the borrower’s industry or broader economy falls into recession.

An unanswered question is whether financial markets can stand the prospective increase given the massive leverage employed for speculation and to fund “carry trades” in which leverage is used to increase the amount of income produced from low-yielding bonds. If markets cannot tolerate much increase, then the question will become at what point will the “Fed put” or “Powell put” be triggered in which further hikes are precluded or even reversed?

No one knows, but this link provides an interesting perspective on the accuracy of forwarding curves. Since the Fed experimented with very low policy rates in the early 2000s when the Fed Funds rate was set at 1%, market participants have projected hikes would commence sooner than occurred. Also, once hiking cycles began, market participants projected less hiking than occurred.

In effect, investors believed rates were too low once reduced to near zero; and once the hiking began, the Fed did not have as much latitude as it thought it had to raise rates given the build-up of debt in the economy and markets.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director