How to Communicate Financial Results to Family Shareholders (Part 3)

According to author Christopher Booker, all stories fit into one of seven basic plots. While details of character, narrative perspective, setting, and the like can make stories appear quite different from each other, any story can ultimately be reduced to one of a handful of basic plots. With respect to literature, we have no idea whether Mr. Booker’s thesis is sound or not, but we have long suspected that something similar is true for family business. Like stories, no two family businesses appear the same, as demonstrated by the old saw that if you have seen one family business, well, then you’ve seen one family business. Yet, despite their many unique attributes, there are only a few basic underlying plot structures that family businesses follow.

More than any other financial statement, the statement of cash flows reveals the basic plot of your family business. The statement of cash flows is the least understood financial statement, so family leaders often ignore it when attempting to communicate financial results to their family shareholders. But for those who know what they are looking for, the statement of cash flows reveals what a company is really up to.

This week, we conclude our series of posts on communicating financial results to family shareholders. Having focused on telling the story of the family business through the balance sheet and income statement, we turn our attention this week to the statement of cash flows.

The Statement of Cash Flows

You can discern the basic plot of your family business by answering two questions. First, what time is it? Second, how are we managing financial risk?

What Time Is It?

For farmers, the changing of the seasons dictates whether it is time to plant or time to harvest. Family businesses are not tied to the cycle of seasons. But at any given time, a family business is either planting or harvesting, and the statement of cash flows tells us what time it is.

The statement of cash flows allocates the cash flows of your family business into three categories: operating, investing, and financing. Comparing the operating and investing cash flows reveals what time it is for your family business. The operating cash flows are those generated by the existing operations of the business. The investing cash flows represent the amounts reinvested in the business (generally either through capital expenditures or business acquisitions).

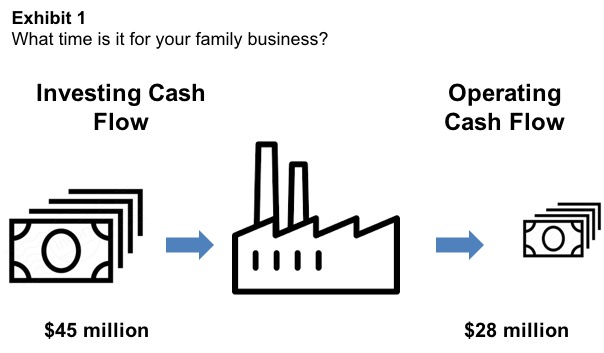

Exhibit 1 illustrates how the investing and operating cash flows interact to reveal the “time” for your family business.

If the investing cash flows (the money being put into the business) exceed the operating cash flows (the money coming out of the business), it is planting time for your family business, as is the case in Exhibit 1. For family businesses in harvest mode, the opposite is true, and operating cash flows are greater than investing cash flow.

Since investing cash flows are often lumpy, we find it best to look at the statement of cash flows on a multi-year basis. Examining cash flows on a rolling three or five year basis helps to eliminate the “noise” that may creep into the results for a single year in which a major capital expenditure of acquisition is completed.

Your family shareholders should know what time it is for your family business, and why. It is not unusual for companies to oscillate between planting and harvesting over time, so a format like that in Exhibit 1 can be used with either historical or prospective cash flows, depending on what message you need to convey to your family shareholders.

How Are We Managing Financial Risk?

Family businesses manage financial risk through capital structure, or deciding how much money to borrow. Companies that are in planting mode need additional capital, and that capital can come from the bank or from shareholders. In contrast, family businesses that are harvesting have “excess” capital to return to capital providers.

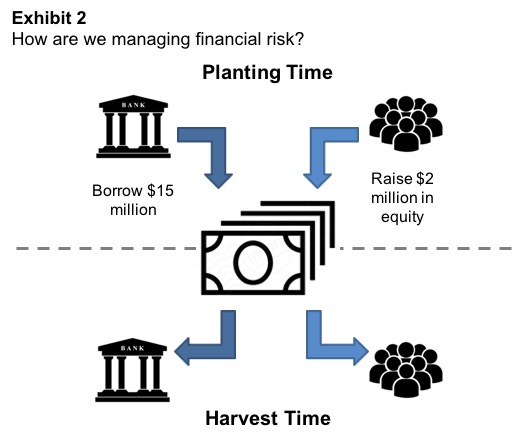

Exhibit 2 illustrates how family businesses manage financial risk through capital structure.

Our planting company from Exhibit 1 needs $17 million of outside capital (the excess of investing over operating cash flows). That capital can come from lenders or in the form of new equity from shareholders. Relying primarily on debt increases the financial risk of the company, all else equal. It also potentially increases future returns to family shareholders.

If it is harvest time, the family business will have “excess” capital that can be used either to repay debt or distribute to shareholders through dividends or redemptions. Repaying outstanding indebtedness is the more cautious approach for harvesters, while making distributions to shareholders is the more aggressive path.

Bringing It All Together: What Is the Plot for Your Family Business?

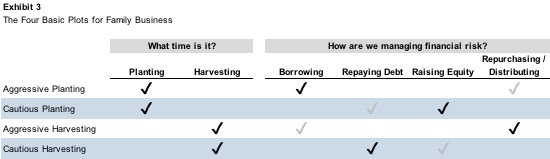

Together, the two questions answered by the cash flow statement (What time is it? How are we managing financial risk?) reveal the basic underlying plot for your family business. Exhibit 3 outlines the four basic plots.

The black checkmarks in Exhibit 3 indicate the dominant story threads for each plot, while the grey checkmarks identify secondary themes that may or may not be present in a particular story.

- Plot #1 :: Aggressive Planting. When family businesses finance their capital needs during planting season with debt, they are following the aggressive planting script. This is the most nail-biting plot of them all, with the uncertainty of future returns from current investment compounded by increasing financial leverage. If the borrowing is accompanied by shareholder distributions, the risk profile is even more elevated.

- Plot #2 :: Cautious Planting. Occasionally family businesses in planting mode will opt to finance their capital needs with new equity rather than debt. Family businesses often eschew seeking outside (non-family) equity capital, so this plot is less common. However, with the number of investment funds seeking minority stakes in family businesses increasing and the growing use of joint ventures and other “synthetic” equity raises, this plot may become more prevalent.

- Plot #3 :: Aggressive Harvesting. Harvesters have “excess” capital to dispose of. Aggressive harvesters prefer to leave existing debt outstanding and distribute to shareholders in the form of dividends or share repurchases. The most aggressive harvesters actually continue to borrow more money to fund even more substantial shareholder distributions.

- Plot #4 :: Cautious Harvesting. More risk averse harvesters view the “excess” capital at their disposal as an opportunity to repay outstanding debt. In other words, rather than provide an immediate return to family shareholders, the companies use the proceeds from harvest to reduce the risk profile of the family business and/or prepare the balance sheet for the next planting cycle.

The narrative details for your family business will be as unique as your family. Yet, the underlying story for your family business ultimately fits into one of these four basic plots. What is yours?

Conclusion

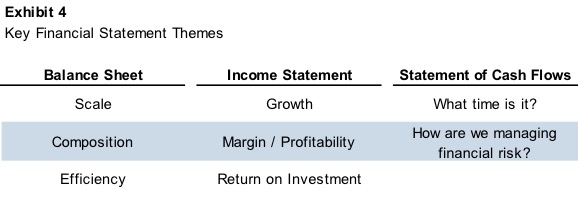

Our objective in this series of posts has been to give our readers some examples of how to communicate financial results more effectively. Financial statements include lots of financial data. The first step in effective communication is identifying the key themes that really matter to family shareholders. Exhibit 4 recaps the key themes we have identified from each financial statement.

Focusing on these key themes will help you prune away unnecessary numbers and details, allowing you to communicate in a way that can actually promote positive engagement among your family shareholders. And that is an investment with a high return.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director