How to Constructively Engage with a Dissatisfied Family Shareholder

Publicly-traded Ashland Global Holdings (ticker: ASH) recently announced a series of steps intended to pacify activist investor Cruiser Capital, which owns approximately 2.5% of the company’s shares. Cruiser has proposed four new directors at Ashland, citing a number of factors contributing to their dissatisfaction with the status quo in a November 2018 letter to the board:

- Ashland’s refusal to engage with industry experts recommended by Cruiser

- Cruiser’s belief that Ashland is “severely undervalued”

- Cruiser’s belief that Ashland “has demonstrated persistent operational underperformance”

- Cruiser’s belief that the board needs new voices to better represent all shareholders

In an effort to head off a protracted and potentially embarrassing proxy fight, Ashland announced earlier this month that it would add two new directors, adjust board committee composition and leadership, and have one long-term director step down. Whether Ashland’s proposed moves will placate Cruiser remains to be seen.

The source(s) of contention among shareholders can simmer for years, ultimately yielding a toxic stew of resentment, strife, or even litigation.

Privately-held family businesses are not exposed to the threat that an activist investor such as Cruiser Capital will accumulate a significant ownership position. But does that mean that “shareholder activism” is something that family business directors don’t need to take seriously? We don’t think so.

In our experience, while family businesses are not vulnerable to activist investors, they may have disgruntled family shareholders to deal with. Given the tangled personal dynamics in family business, directors would probably prefer to deal with a third-party activist investor like Cruiser Capital than an unhappy sibling or cousin. Since family business ownership interests are illiquid, the source(s) of contention among shareholders can simmer for years, ultimately yielding a toxic stew of resentment, strife, or even litigation.

We noted the specific items Cruiser was taking umbrage to above – what would a list of disgruntled family shareholder complaints look like? The most common points of contention include the following:

- The family business is not paying a sufficient dividend

- The family business is being run by the wrong family members

- The family business is not making the right investments

- The family business board needs some fresh faces

- The family business holds too much cash or other non-operating assets

- The family business is engaging in related party transactions on an unfair basis

- The family business is not as profitable as it should be

- The family business management team is over-compensated

The list could certainly go on. Sometimes such complaints have merit, and sometimes they don’t. Yet even a perceived problem is a real problem to the discontented family shareholder.

The authors of a 2018 article on the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation identify three components of an effective response by public companies to activist investors. The recommendations translate well to family business boards dealing with one or more disgruntled family shareholders.

1. Objectively Consider the Activist’s Ideas

Of course, all families are different, but just because Uncle Harry makes a recommendation does not necessarily mean it’s wrong. It is difficult, but necessary, for family business directors to lay aside whatever personal dynamics may be at work and objectively evaluate the economic merits of the proposed action. This could involve going beyond intuition and “gut feel” for a question and gathering relevant data that can inform the decision. Family shareholder activism will naturally be perceived by management and the board as personal (and in some cases the complaints may be truly personal and nothing more). However, family business directors have a duty to make appropriate decisions for the long-term sustainability of the business even if their feelings have been hurt. Sometimes, a major change is the right thing to do, even if it is uncomfortable. The presence of independent non-family board members or trusted advisors can help family directors filter out potentially distracting personal dynamics and evaluate proposals on their merits.

2. Look for Ways to Build Consensus

The authors of the article suggest finding points of agreement with activist shareholders. In the context of family businesses, the first step is to demonstrate a commitment to objectively evaluating the shareholder recommendation by actually talking to the shareholder about his or her concerns and proposed action. Stonewalling or ignoring the shareholder will only make the situation more combustible. Engaging with the shareholder may reveal that a relatively simple “fix” may exist that neither the frustrated shareholder nor the board had previously considered.

The second step would be to solicit input regarding the contested issue from a broader selection of family shareholders. This can be done through informal conversations or through a more structured confidential survey process. Soliciting other opinions may confirm that the disgruntled shareholder is merely giving vent to what are ultimately personal frustrations, or it may reveal to the board that there is, in fact, a broad consensus among family shareholders that the issue is a real problem that needs to be addressed. In either event, the process will demonstrate to the activist shareholder that their concerns are being taken seriously.

3. Tell the Company’s Story

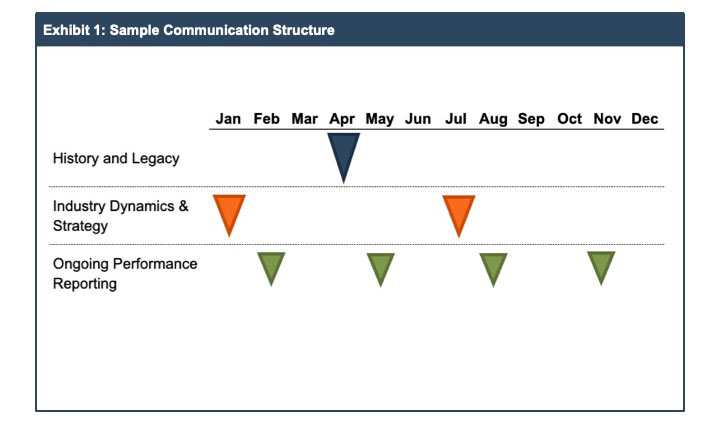

The best defense, as they say, is a good offense. Similarly, the best way to deal with disgruntled family shareholders is to foster positive engagement with all shareholders before any of them become disgruntled. Senior management and the company’s directors should always be telling the company’s story to the family group. There are three basic levels of family business storytelling:

History and Legacy

Every family business has a “founding myth” that informs the company’s culture and ethos. At appropriate family forums, senior managers and directors should tell and re-tell the company’s story so that it becomes firmly embedded in the family’s DNA. Some even advocate using dedicated spaces to serve as continuous reminders of the company’s history and legacy.

Industry Dynamics and Strategy

Family shareholders should have the opportunity, through periodic education opportunities, to understand the broad contours of how the relevant industry works and the family business’s place in that industry. Non-employee family shareholders should understand the primary production inputs required, the value-added processes of the company, the attributes of customers, key regulatory issues, and the nature of competitive rivalry in the industry. This background knowledge will provide the basis for shareholders to understand the company’s basic strategy and the implications of that strategy for dividend policy, capital budgeting, and financing decisions.

Ongoing Performance Reporting

The sad truth is that public companies treat their anonymous shareholders better than many family businesses treat their family shareholders. Public companies provide regular, detailed communication to their shareholders regarding how the business is performing and what the future looks like for the business. Yet many family businesses do not have a schedule of regular communication with shareholders to keep them informed on the performance or outlook for the business. Merely sending out financial statements is not enough, however. Management and directors need to convert the raw financial data into information that tells the company’s story.

Most cases of family shareholder strife can be traced to a failure to communicate.

We’ve never heard about a disgruntled family shareholder that complained about knowing too much about the family business or receiving too much relevant communication from the company. Rather, most cases of family shareholder strife can be traced to a failure to communicate. The most appropriate intervals, format, and content for shareholder communication will not be the same for every business, but an effective communications program will include all three of the elements discussed above.

Conclusion

Are all of your family shareholders positively engaged with the business? The cost of failing to engage with shareholders in a constructive way can be very high. Whether it is providing an independent perspective on shareholder disagreements, helping develop consensus on contentious issues, or crafting an effective shareholder communications program, our family business advisory professionals are eager to assist you and your fellow directors in promoting positive shareholder engagement. Call us today to discuss your situation in confidence.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director