(More) Lessons for Family Business Directors

From the Failure of Silicon Valley Bank

This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from our firm’s founder, Chris Mercer. Before establishing Mercer Capital in 1982, Chris worked in the banking industry, and in its early days (during the height of the Savings & Loan crisis), many of the firm’s clients were troubled financial institutions. In this post, Chris brings his decades of experience to bear in analyzing the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and identifies four critical lessons for family business directors, regardless of industry. We hope you enjoy it!

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank will be talked about for years. What really happened? What caused SVB to fail? Was it just the long-term Treasury securities that everyone has talked about? Well, no. SVB was on a self-imposed path to destruction that had been waiting for an adverse change in the economy or a rising interest rate environment to kick it into oblivion.

There are lessons to be learned for family business directors from this recent event.

A Short Digression from SVB?

In 1985, Mercer Capital was in two businesses: problem bank consulting and business valuation. By 1987, we had worked our way out of the consulting business and were solely a valuation firm. But there are some memories from our consulting days that are relevant to SVB.

I went to Park Bank of Florida’s board meeting in St. Petersburg in the latter half of 1985 to meet with its board of directors. They had recently announced loan problems and losses and sought to hire a consulting firm to help them work through their problems. Here’s where things stood:

- Park Bank had grown very rapidly, increasing total assets from $8 million to $750 million in eight years.

- The bank went public in 1982.

- The bank was profitable and attractive for those eight years when it announced underlying asset quality problems.

- Management and the directors prided themselves on being creative bankers and, in retrospect, thought they were smarter than other bankers.

- The bank’s board and management were rather cocky, bragging in marketing campaigns about the bank’s sophistication and elitism.

- The board and management literally bet the bank on their alleged creativity and ability to structure loans better than other banks.

But, the general attitude was different when I met with the board. While Mercer Capital was retained, I basically lived in St. Petersburg for several months while we attempted to help management address complex problem loans and gain control over operating expenses.

Unfortunately, the problems were so deep that a solution was not possible. In 1986, the FDIC closed Park Bank of Florida. At the time, it was the sixth-largest bank failure in history.

The Lessons

There are several lessons for family business directors from the failure of SVB (and Park Bank of Florida).

- Don’t grow too fast.

- Don’t grow staffing too fast.

- Don’t smoke your own stuff.

- Don’t make “bet the company” decisions.

Don’t Grow Too Fast

Unless you are a budding Amazon with unlimited public and private funding, you cannot grow indefinitely without the prospects for reasonable returns. Business value is ultimately a function of expected cash flow growth and the risks of achieving that expected growth.

SVB was racing against the banking industry to collect deposits for its balance sheet. Deposit liabilities are the major funding source for most banks, and their deposits get deployed into loans, investments, and other earning assets. Let’s look first at SVB’s total assets.

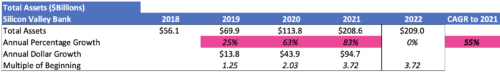

SVB had total assets of $209 billion at year-end 2022, making it the 16th largest bank in the country (out of 4,116 banks) at that time. SVB grew its total assets from $56.1 billion at the end of 2018 to $209 billion at the end of 2021, or at a compound annual growth (CAGR) rate of 55% per year. Those are just numbers, but let’s look at them.

Click here to expand the image above

SVB grew assets by some $13.8 billion in 2019. To put this in perspective, Sandy Spring Bank, the 107th largest bank in the nation, had that many assets at year-end 2019. But Sandy Spring Bank accumulated its $13.8 billion in assets over more than 150 years, not one year.

SVB grew its assets at higher rates and larger dollars in 2020 and 2021. The bottom line is that SVB grew its assets each year at amounts equal to some of the largest banks in the country after their many years of historical growth.

The nation’s 4,116 banks grew assets at a 12% CAGR in the three years ending 2021 (versus 55% for SVB). The focus is on growth to 2021 because growth ceased for SVB in 2022 and slowed significantly for the banking industry as well.

When I was consulting, I talked about the “Law of the Double.” When a company doubles in size, it is necessary for its management, accounting, finances, human relations, systems, and everything else to adapt to the larger size.

If a company doubles in size in 10 years or at a CAGR of just over 7%, change is evolutionary and occurs mostly without much pressure. When a company doubles in size in two years, as SVB did from 2018 to 2020, the internal pressures on systems are incredible, and those pressures got even worse when the bank grew its assets another 83% in 2021.

Silicon Valley Bank grew too fast to maintain proper controls at all levels of the organization.

Don’t Grow Staffing Too Fast

Hiring good people is difficult for almost all businesses, whether employment is tight or not. Hiring many good people at the same time is even more difficult. Take a look at the employment growth at SVB:

Click here to expand the image above

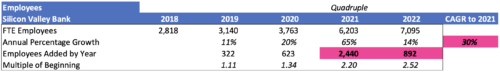

SVB hired 322 net new employees in 2019, 623 in 2020, and 2,440 in 2021. Imagine the internal resources necessary to identify and hire that many people. Given the numbers above, SVB hired 3,385 employees in three years and grew staff at a CAGR of 30%. For comparison, the entire banking industry’s staffing grew at a 2% CAGR over the same period.

Assuming no turnover in the 2,818 employees at the end of 2018, their employment more than doubled. That meant more than half of all employees had less than 2.5 years of experience, and about 40% had been with the bank for less than one year.

SVB had very little of what I call “institutional memory.” How could management train so many new employees? How could management instill any sense of corporate culture with so much change? The answer is they could not.

This kind of growth in a banking business is a precursor of future problems.

Silicon Valley Bank grew staffing too fast.

Don’t Smoke Your Own Stuff

Silicon Valley Bank was founded in 1983 and grew to become a $56 billion bank over the next nearly 40 years to 2018. Assuming they started with $100 million in total assets, that represented an 18% CAGR over the period. To put this growth rate in perspective, had SVB grown at 18% per year from 2018 to 2021, it would have been a $92 billion bank rather than a $209 billion bank.

SVB management had to believe they had a better mousetrap than other bankers. The board of directors had to have bought into that mousetrap to allow such uncharacteristic and unprecedented growth.

But money is all green. Loan and deposit markets are competitive. Loans are made based on price, service, and quality.

- Pricing relates to the interest paid by borrowers. Other things being equal, banks offering lower interest rates get the loans.

- Service is defined by how bankers treat their customers. Service and relationships are important, but they only go so far.

- Quality is a function of the structure and collateral of loans. From a bank’s viewpoint, unfavorable structures and collateral can help it gain loan market share.

The bottom line is that growing loans faster than the market for a sustained period (33% CAGR to 2021) increases the probability of future problems for a bank. There has been little talk about loan quality issues at SVB. It will be interesting to see how the portfolio performs under the new ownership of Citizens Financial.

A bank’s managers and directors have to be smoking some of their own dope to believe that it can sustainably outgrow its industry by a large margin.

Silicon Valley Bank’s managers and directors were smoking their own stuff.

Don’t Make “Bet the Bank” Decisions

Faced with interest margin pressures in the “zero interest rate environment” leading up to the end of 2021, SVB management had options. Banks are required to engage in what is called “asset-liability” management. They are required to consider the impact of future interest rate changes on their interest-earning assets and their interest-paying deposits.

When I was Assistant Treasurer of First Tennessee National Corporation (now First Horizon), we had to model the impact of interest rate changes for incremental strategies involving loans, investments, or deposit liabilities. Strategies that the Finance Committee considered to be too risky were not approved. The goal of asset-liability management then, and as it is now, is to develop stable and reasonably defensive earning streams.

On October 1st, 2021, the common stock of SIVB, SVB’s parent, peaked at $717 per share. The price then began a steep decline, reaching a low of $230 per share before rallying to $302 per share at the end of 2022. Management and the board were under tremendous pressure to generate performance that they hoped would stabilize the stock price.

They made the wrong decision. They took the nearly $100 billion in deposit growth from 2021 and put the majority of it into long-term term securities with maturities in excess of 10 years. When SIVB’s stock price peaked in October 2021, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yield was on the order of 0.70%, just off the record low from a few days before of 0.64%.

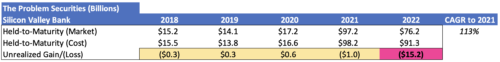

The pressure for yield at SVB, and banks in general, was historic in nature. Over a fairly short time in late 2021 and early 2022, in the face of enormous margin and earnings pressure, management decided to invest more than $80 billion in long-term (10-year or more maturities) Treasury securities at an average yield of about 1.75%. The result is in the next figure.

Click here to expand the image above

SVB management bet interest rates would not rise in late 2022 and 2023. And they made the bet with about 40% of the bank’s balance sheet. When rates rose, the bank was not in a position to benefit from reinvesting shorter maturity securities nor in a position to avoid the earnings pressure of low-rate, long-term investments in a rising rate environment.

The offending securities in the figure above are called “held-to-maturity” and are treated so they can be carried on the balance sheet at cost. However, they do have market values, and those are shown above. The held-to-maturity securities had a cost basis totaling $91 billion compared to the market value of only $76 billion at year-end 2022.

There is an inverse relationship between interest rates and bond prices. When rates rise, bond prices fall. When maturities are long, bond prices fall a great deal.

The unrecognized loss of $15 billion approximated SVB’s equity capital of $15.5 billion. When these financials were disclosed, as the old saying goes, “the jig was up.”

SVB “bet the bank” on an interest rate forecast that few believed in, and lost.

SVB Failed

The FDIC shut Silicon Valley Bank down on March 10th, 2023. There is talk about a “rush to justice” and that if SVB had had just a little more time, it could have weathered the massive deposit outflows that ultimately caused its failure.

From my perspective, the bank had already failed regardless of the action of the FDIC on March 10th.

That is not the case for the vast majority of family businesses. Nevertheless, it is good to take our lessons from whence they come.

Recap for Family Business Directors

What are the lessons for family business directors who are not on the board of Silicon Valley Bank, but of various kinds and sizes of companies around the nation?

We recapped them above, but in summary:

- Don’t grow too fast. It is hard enough to keep your eyes on the ball when growing at market rates for your industry. The problems are exacerbated if your company is trying to grow at greater rates than your competitors or your industry. And remember the “Law of the Double.” Your management, systems, and everything else has to adapt to handle that growth. If you double too quickly, you may not be able to adapt.

- Don’t grow staffing too fast. This lesson is a subset of the first one but warrants particular attention. Rapid staff growth decreases average experience, requires substantial training, and dilutes institutional memory. It also makes it difficult to inculcate your company’s culture into the new staff.

- Don’t smoke your own stuff. When things are going well, it is easy to believe your group is “above average,” like all the children in Lake Wobegon. When management teams begin to think this way, it becomes difficult to bring your normal level of judgment and scrutiny to major decisions. Recall that sage warning that “pride goeth before the fall.”

- Don’t make “bet the company” decisions. Important decisions must be made, and they always have some risk. However, companies should avoid, to the extent possible, those individual decisions that can put the entire company at risk. You’ll know one the next time you see one.

There are, indeed, lessons for family business directors from the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Are we suggesting that you should not grow? Of course not. But good growth is planned growth that preserves markets or margins or both.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director