Out to the Public and Back Again

The Weber Grill Case Study

A recent Wall Street Journal article highlighted the trend of newly-public companies reverting back to private ownership after a very short time in public hands. Among the boomerang IPOs mentioned in the article was that of backyard grill maker Weber. With the advent of grilling season, we were curious about Weber’s experience in the public markets and any lessons that family business directors might be able to draw from the tale.

Pre-IPO Background

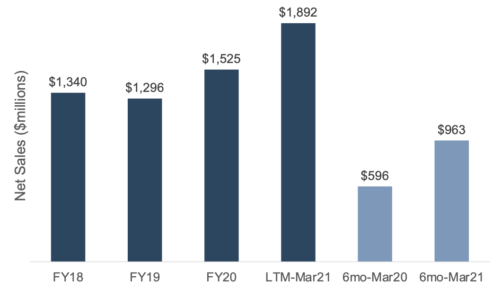

Weber has been selling the iconic kettle charcoal grill since the 1950s. In 2010, BDT Capital Partners acquired a majority stake in the company from the founding Stephen family. As with many “home-focused” consumer goods companies, the pandemic was good for Weber’s business. Amid COVID restrictions, grilling was hot. During the six months ending March 2021, Weber sold $963 million worth of grills and accessories, compared to $1.3 billion for the pre-pandemic year ending September 2019.

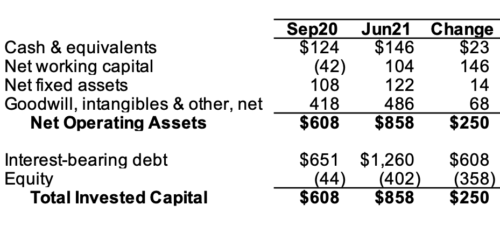

In January 2021, Weber added a new recipe to its growth cookbook, spending $142 million to acquire June Life, a smart appliance and technology company. The rapid organic growth and acquisition activity required capital, and Weber executed a new $1.25 billion credit facility in October 2020.

Prior to the August 2021 IPO, Weber used approximately $442 million of the loan proceeds from the new credit facility for a combined redemption and distribution to the existing owners during 2Q21.

The Offering

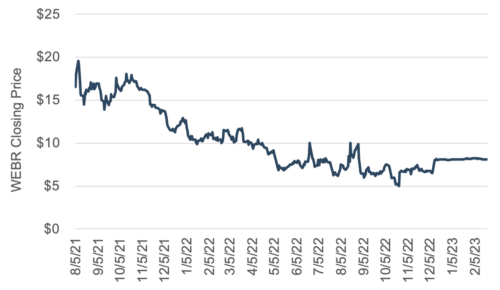

The market’s reception to the offering was cool. While the initial S-1 filed anticipated the sale of 46.9 million shares at a midpoint price of $16 per share (gross proceeds of $750 million), the August 2021 initial public offering was instead priced at $14 per share on just 17.9 million shares for gross proceeds of $250 million. Lower IPO proceeds translated into more post-IPO debt for the Company. In September 2021, Weber reported total interest-bearing debt of $1.0 billion (3.4x adjusted EBITDA); had the IPO netted the planned proceeds of $750 million, the debt could have been cut in half. The IPO price implied a multiple of approximately 16.8x FY21 adjusted EBITDA of $307 million.

Post-IPO Operating Performance

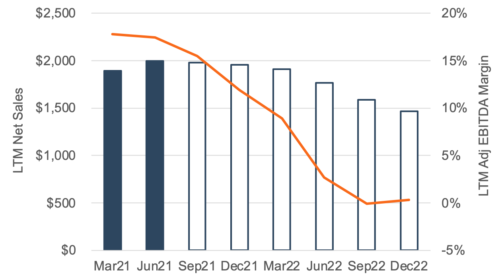

It turned out that investors’ skepticism toward the IPO was warranted. The robust sales and adjusted EBITDA generated during the pandemic proved unsustainable. During calendar 2022, revenues fell below $1.5 billion, and with escalating costs, adjusted EBITDA for the year evaporated.

The sharp earnings deterioration following the IPO precluded deleveraging, and public investors lost any enthusiasm they may have had for the shares by early 2022.

Private Again

On October 24, 2022, just 14 months after the IPO, Weber announced that BDT would be taking the company private at a price of $8.05 per share. The going private price represented a 60% premium to the previous stock price of $5.03 per share. That premium was small comfort, however, for investors who had been along for the ride since the IPO at $14 per share. The brief saga of Weber as a public company resulted in no change in ownership of the company and a $106 million loss for public investors.

Lessons for Family Business Directors

The tale of Weber’s brief history as a public company is interesting. Among the lessons available for family business directors from the tale, we will focus on two for this post.

Lesson #1 – Distinguish between short-term opportunities and long-term trends. The restrictions on public dining during the first year of the COVID pandemic represented a favorable opportunity for a company like Weber. On a year-over-year basis, net sales for the six months ending March 2021 increased 62%, while adjusted EBITDA grew 143%.

But a Weber grill is a durable consumer good. So, the challenge for managers in a situation like that is to disentangle the increase in short-term demand from the change in long-term demand. Was the boom in grill sales sustainable, or an acceleration of grill purchases that would have been made in subsequent periods? Of course, there is no precise way to distinguish the two in real-time, and managers should identify strategies to convert short-term opportunities into long-term trends.

The temptation for managers to take advantage of short-term opportunities is to allow the temporary costs necessarily incurred to exploit the opportunity to become embedded in the company’s operations. When this happens, margins suffer when the short-term opportunity passes.

In Weber’s case, the company generated adjusted EBITDA of $189 million on pre-pandemic net sales of $1.3 billion in fiscal 2019. However, in the wake of extraordinary pandemic demand, the Company could only eke out adjusted EBITDA of $5 million on $1.5 billion in sales during calendar 2022. Clearly, some of Weber’s historical cost discipline was lost amid the short-term opportunity.

Lesson #2 – Don’t forget that sellers know things, too. As we mentioned previously, the market participated in the Weber IPO reluctantly, buying a smaller number of shares at a lower price. However, those investors who did participate got burned, incurring a 42.5% loss in just a little over a year. We are not suggesting anything untoward in BDT’s behavior in the public offering, but it is a good reminder for family business directors that, when considering an investment, especially a business acquisition, it is important to consider the seller’s motivation in the transaction.

There is an inherent information asymmetry in corporate M&A transactions: the seller will always know more about the company than the bidders. That is why robust due diligence in the acquisition process is so critical. But family business directors need to think strategically beyond the basic legal, accounting, and tax diligence that is a prerequisite for any transaction. What is the underlying rationale that makes this deal make sense for us? Why are we better owners of this business than the sellers? In our enthusiasm for the deal, have we begun to bid against ourselves? Or do we risk missing a unique opportunity by trying to extract the last nickel from the transaction? An outside perspective from an experienced financial advisor can be invaluable in helping identify and formulate answers to these types of questions.

Conclusion

We don’t anticipate the round-trip IPO being the next big trend for family businesses. However, whenever you pull out your grill this spring and summer, we hope you’ll remember the Weber IPO and take its lessons to heart. If you are contemplating an acquisition or other significant corporate transaction, give one of our seasoned financial advisors a call to discuss your plans in confidence.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director