Private Equity Investors Learn What Family Shareholders Have Always Known

Since the turn of the century, pension funds have increasingly turned to private equity investments in a bid to earn higher returns. As detailed in a recent Wall Street Journal article, pension funds have boosted private equity allocations from just 3% of their portfolios in 2001 to 14% in 2023.

The strategy was generally effective as average private equity returns over the past 20 years (as calculated per the MSCI index) outpaced the S&P 500 by over 4.0% per year (14% for private equity, compared to 9.7% for the S&P 500). For those inclined to do the math, the difference between earning 14% per year and 9.7% per year over 20 years is fairly dramatic: at 9.7% per year, $100,000 grows to approximately $637,000, but at 14% per year, that same $100,000 mushrooms to $1.37 million.

So while the private equity bet has paid off in terms of return, pension funds and other private equity investors are beginning to feel the risk that helped generate that extra return. Over the long run, returns follow risk, and private equity funds have provided outsized returns by taking outsized risks, the most significant of which are higher levels of financial leverage and accepting illiquidity.

Private equity investors get their money back when funds sell underlying portfolio companies. Higher interest rates have slowed the pace of exits and, by extension, cash flows back to pension funds and other PE investors. For investors wanting their money now because they either can’t afford to or don’t want to wait for the M&A market to return to strength, getting liquid comes at a cost. The WSJ article reports that transactions on the “secondary market” for private equity interests occur at an average discount of 15% to the value of the underlying portfolio assets.

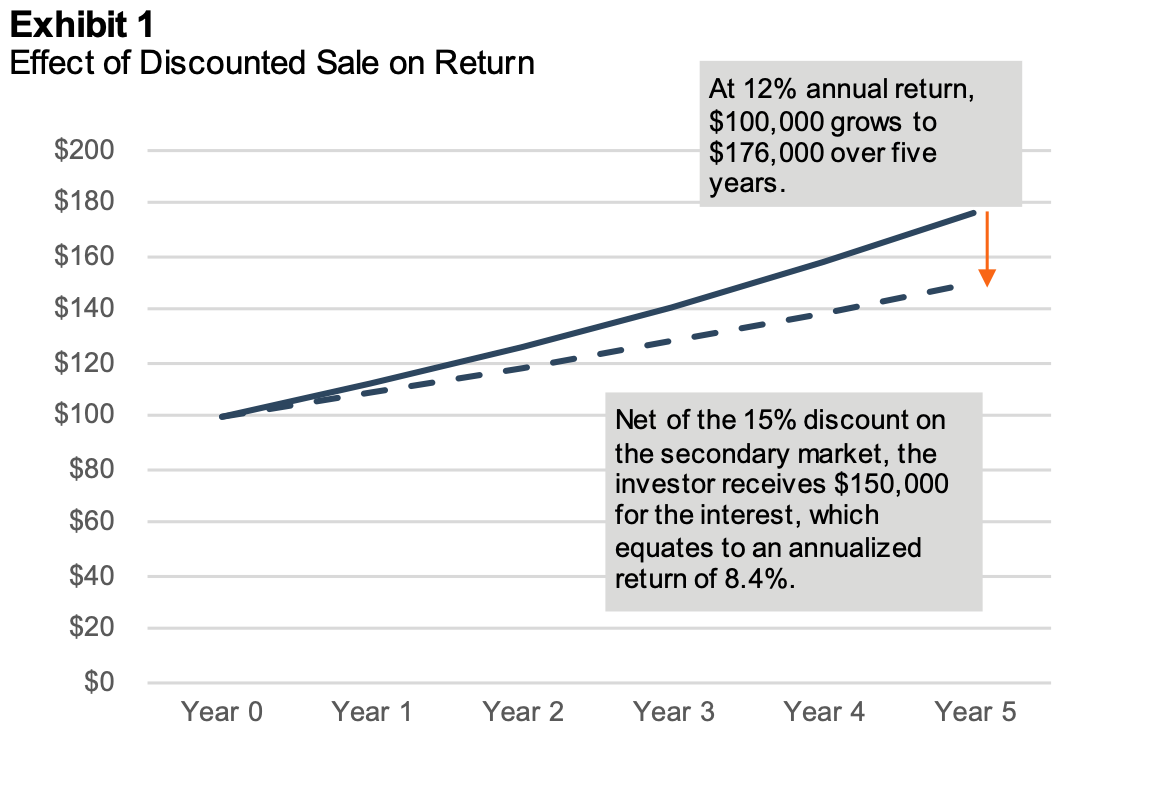

Exhibit 1 illustrates the impact of selling at a discount on a private equity investor’s realized return.

If the PE investor elects to sell their interest “early” on the secondary market at a 15% discount, a 12.0% private equity return shrinks to an 8.4% realized return (assuming no interim cash flows).

What Family Shareholders Already Knew

Maybe some pension fund managers currently feeling the pain should have interviewed a few family business shareholders before committing to private equity as an asset class. One such manager is quoted in the WSJ article lamenting the illiquidity of private equity interests: “You’ve got a lot more money out and going out than is coming back, and I think that is causing a lot of angst.”

We’ve heard that pension fund manager’s sentiment from scores of family shareholders over the years. What most family shareholders already knew – and pension fund managers are learning – is that illiquidity is a real risk. If you want the incremental return associated with that risk, you have to bear that risk. Otherwise, you will sell at a discount and lose the return.

In some ways, the pain of illiquidity for family shareholders can be more acute than that felt by pension fund managers. After all, while chilly M&A markets may delay liquidity for pension fund managers, they can be relatively sure that it will eventually come. For family shareholders, the wait can be uncertain and potentially indefinite. Furthermore, PE funds typically distribute proceeds as portfolio companies are sold, so pension funds have likely received some interim liquidity even if they have to wait longer than expected to sell the last portfolio company standing. In contrast, plenty of family shareholders wait on liquidity with no substantial dividends to provide solace in the interim.

Illiquidity and Family Shareholders

Family shareholders bear the risk of illiquidity. On the one hand, that can be an attractive feature so long as the incremental risk is rewarded with incremental return. On the other hand, as we can see in the secondary market for private equity interests, shareholder liquidity needs don’t always align with corporate liquidity opportunities. Investors accessing liquidity “ahead” of schedule pay the price in the form of selling at a discount.

So what can family businesses and family shareholders do to manage the burden of illiquidity? Five things come to mind:

1. De-stigmatize liquidity requests. In some enterprising families, having a personal liquidity need is viewed as an act of betrayal. This is not necessary and not helpful. Continuing to own all the shares one inherited in the family business is not a litmus test for whether one is a “good” family member.

2. Don’t hoard capital. Be realistic about whether your family business can effectively deploy all the capital its operations generate. If there are good internal uses for corporate earnings, great, but if not, it is better to distribute capital than hold it hostage inside the family business.

3. Be strategic about ownership. Not all members of your family have the attributes (risk tolerance, wealth diversification) that make for ideal family shareholders. If you were starting with a blank sheet of paper today, what ownership group within the family would provide the best foundation for long-term sustainability? If that looks different than the actual shareholder list today, perhaps it is time to make some changes at the margin to move closer to that ideal.

4. Adopt a portfolio mindset regarding debt. Some families are debt-averse, and that is okay. However, if that is rooted in general risk aversion, consider a broader perspective on what constitutes risk. At the shareholder level, a portfolio consisting of diversified assets alongside ownership in a prudently leveraged family business may be less risky than a portfolio consisting solely of ownership in a debt-free family business.

5. Prioritize diversification. Family shareholders should recognize that owning shares in a family business is inherently illiquid. Being well-diversified — both in terms of household wealth and income — can relieve much of the pressure of holding illiquid shares in the family business.

There are no easy answers to the illiquidity puzzle. But family business directors and shareholders both need to be realistic about what illiquidity means for their family and what steps can be taken to mitigate the pain of illiquidity.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director