Questioning Your Family Business Balance Sheet

If the income statement is a movie that records how your family business performed during a particular period, the balance sheet is a snapshot that records what your family business looked like at a particular date.

The balance sheet answers two core questions:

- What are the assets our family business owns? and,

- How has our family business paid for those assets?

We’ll flesh out the first question in this week’s post, and turn our attention to the second question in a subsequent post.

What is an asset?

While we are generally dismissive of accountants on this blog, the bean-counters actually do an admirable job of defining what an asset is. According to accountants,

Assets are probable future economic benefits obtained or controlled by a particular entity as a result of past transactions or events.

The defining characteristic of an asset is that it represents a future economic benefit. So, as you study your family business’s balance sheet, your focus should not be on how much the various assets cost, but instead on what future economic benefits those assets will generate. As a family business director, you need to focus not just on what assets your business owns, but more importantly, why your family business owns those assets.

Family businesses report many different assets, but it is generally helpful to classify them under four broad headings.

- Cash & equivalents. Cash is obviously an asset, but a rather peculiar one, as the probable future economic benefits generated by cash are quite limited. While too little cash will lead to insolvency and failure, too much cash dilutes the returns generated for shareholders.

- Working capital. Working capital consists of accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses, net of accounts payable and accrued expenses. Working capital is the “grease” that makes a family business run smoothly. While an appropriate amount of working capital is essential, family businesses should be aware of the diminishing marginal utility of working capital. As the amount of working capital exceeds the level necessary to operate the business, the incremental future economic benefits associated with working capital get smaller and smaller.

- Net fixed assets. Net fixed assets include real estate, production equipment, rolling stock, and other long-term productive assets of a business. One of the most important tasks of a family business director is ensuring that the business has deployed the right assets in the right places to execute the company’s strategy and capitalize on the available market opportunity.

- Net other assets. Family businesses own sundry other long-term assets (minority investments in other businesses, goodwill & intangible assets from previous business combinations, and deferred tax items are common examples).

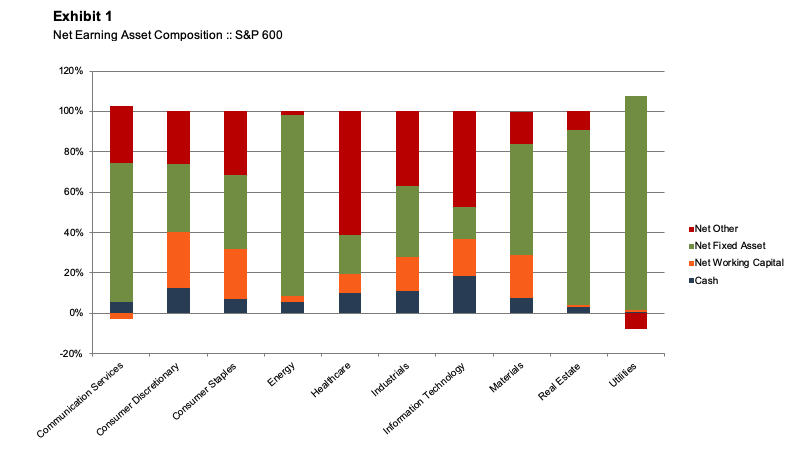

Table 3.2 of The 2019 Benchmarking Guide for Family Business Directors summarizes balance sheet composition for the companies in our data set by industry. Exhibit 1 below summarizes the data for the small cap (S&P 600) companies in our benchmarking universe.

Examining the data for the public companies, we think there are four questions that family business directors should think about with regard to their company’s asset base.

1. What is your family business’s cash strategy?

We see cash fulfilling a number of different roles for our family business clients:

- Liquidity to meet current obligations as they come due. This is the most fundamental (and necessary) use of cash in a family business. Do you have a target level of cash to meet the operating needs of the business?

- Sinking fund for future capital expenditures or debt repayment. Accumulating cash balances to pay for anticipated investments or loan repayments can eliminate transaction costs for financing events, reduce interest expense, and reduce the risk that credit will not be available when needed. These are worthwhile objectives for many family businesses, but there is a cost to these benefits in the form of depressed returns on family capital.

- Hedge against uncertainty. Some family businesses maintain additional cash balances to provide a margin of safety against the uncertainty inherent in their business model. We can see some evidence for this in Exhibit 1, as utilities, which generally face the least near-term uncertainty regarding operations, also carry the smallest cash balances.

- Insurance against failure of corporate strategy. Eventually, prudent risk management morphs into unhealthy risk aversion as some family businesses hold such large cash balances that they are no longer hedging uncertainty, but attempting to insure against failure. In addition to dragging down returns of family capital, this use of cash can promote management complacence (we never have to worry about making payroll, etc.) or encourage inefficient capital investment (all that money does eventually burn a hole in someone’s pocket). Directors should carefully evaluate just whose risks are being managed in this case: the family shareholders, or management?

- The asset of last resort. Finally, for some family businesses, cash can become the asset of last resort. This most often reflects some degree of family dysfunction, often expressed in the belief of family leaders that family shareholders can’t be trusted with dividends, so the money is safer in the company. And if the company doesn’t have a productive use for the capital, it just sits there, weighing down returns on family capital.

2. What opportunities do you have to optimize your cash conversion cycle?

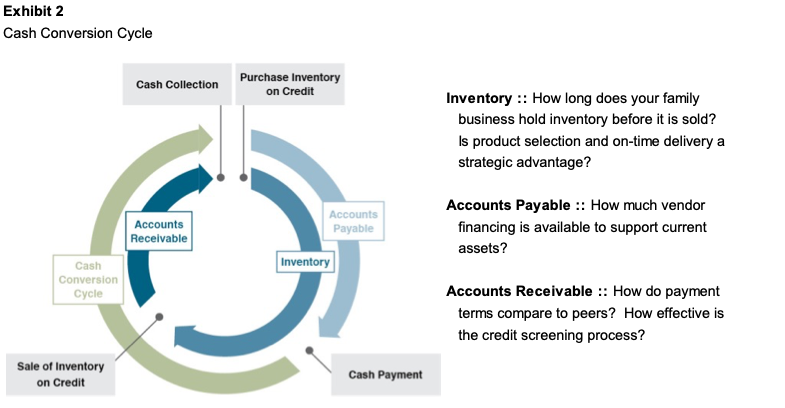

The most comprehensive measure of working capital management is the cash conversion cycle, which measures the time elapsed from when cash is paid for inventory to when cash is received from customers. Different industries and business models have different cash conversion cycle expectations. As noted in Exhibit 15, some sectors (industrials and materials) require significant inventory balances, while others that rely on subscription-based models (communication services) actually have negative cash conversion cycles. Exhibit 2 illustrates the cash conversion cycle and identifies some key questions for family business directors with regard to each major component. Less working capital is not always best; there may be potential strategic advantages to maintaining deep inventories or providing generous customer financing terms, but if such is the case, the rationale and corresponding benefits (superior pricing, etc.) need to be clearly noted.

3. How effective is your capital budgeting process?

The balance of net fixed assets is the cumulative result of all the capital budgeting decisions your family business makes. How effective is that process? Do managers have a clearly-articulated strategy that guides what sorts of capital investments are needed? Has the board established hurdle rates for capital investment to define financial feasibility for proposed projects? Does the company have a strategy for minimizing the impact of cognitive biases that lead to over-optimistic projections? Is there a feedback mechanism in place to ensure that actual results are compared to projections for proposed capital projects? As evident from Exhibit 1, net fixed assets account for a large portion of the total capital invested in businesses; as a family business director, you should be diligent to ensure that the capital budgeting process works to advance the company’s strategy.

4. Do you know what makes your family business valuable?

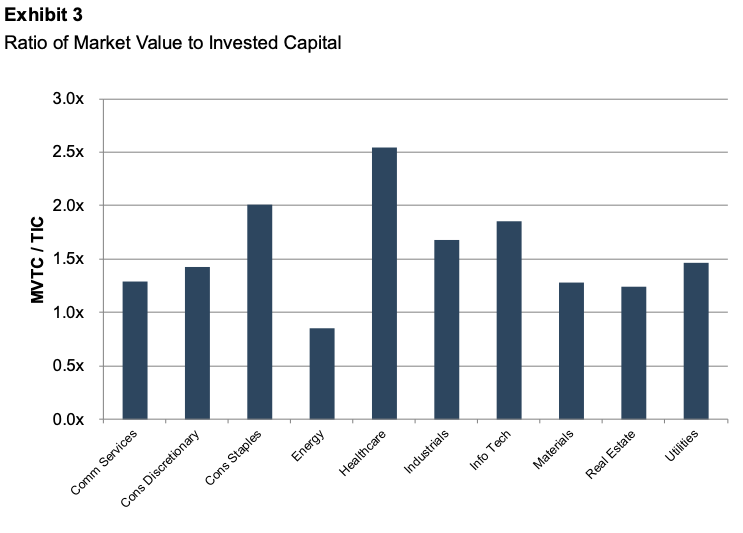

This is not the same thing as knowing what your family business is worth (although that is important, too). Instead, the focus is on understanding what the core attributes of your family business make it valuable. In one sense, your family business can be viewed as a portfolio of assets. If those assets work together in executing an effective strategy that takes advantage of – and builds – the company’s sustainable competitive advantages, the value of the whole can be far greater than the sum of the individual assets. Exhibit 3 summarizes data from the S&P 600 companies in our data set comparing the market value of each public company to the total invested capital (or sum of the asset values). The overall median for the group is approximately 1.6x, meaning that for every $1.00 of capital invested in the business (whether debt or equity), the assets work together to generate $1.60 of market value.

The dispersion of individual observations is quite wide, however. Some of the companies actually experience a negative relationship between market value and invested capital (i.e., they turn $1.00 of investor money into assets valued by the market at less than $1.00). The competitive advantages that drive higher market values become progressively more difficult to sustain. The bottom line is that each of the companies with ratios well above 1.0x has a story and a strategy that support their market valuation. What is your family business’s story and strategy? What makes it valuable? Without a clear answer to these questions, your family business is likely to get “stuck” and eventually experience slowing sales growth and shrinking returns, both of which have unpleasant side effects on the family.

As a family business director, your role is akin to that of a portfolio manager. As a good portfolio manager, you should care not just what assets your family business owns, but why it owns them. In other words, what makes your family business valuable, and how does the current portfolio of assets contribute to enhancing and sustaining that value?

Family Business Director

Family Business Director