Selling Your Family Business

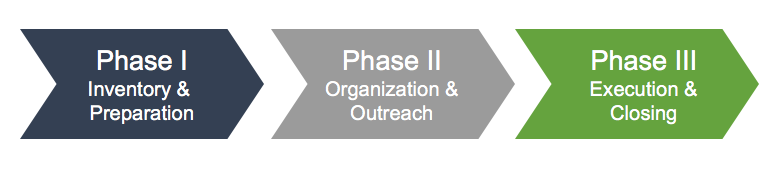

Selling a business is a three-step process. Some sellers elect to stop at Phase I or II and don’t proceed to closing, while others decide to complete the transaction process. In reality, each of the phases overlaps to some degree, making the process more of a continuum than a finite set of procedures. A turnkey, orderly process will often require four to six months. When extra time is required to prepare and/or when multiple rounds of market outreach are involved, we’ve managed deals that required six to eighteen months and more to reach a close or no-close decision.

Ultimately, the collective team goal as seller and advisor is to win the race, whether it be at the pace of the hare or the tortoise.

Phase I involves “taking inventory.” Taking inventory means gathering and analyzing financial and operating data for the family business. The milestone goal of this process for most clients is obtaining a valuation in order to establish decision-making baselines and to set transaction expectations. The valuation undertaking helps the advisor learn about the business and relate the “story” of the business to the financial and operating data for the company and its industry. Equally important, Phase I promotes forthright discussions about family and ownership objectives that in turn help the advisor identify the selling family’s priorities and preferred transaction structures. Telling the company’s story in a clear and compelling way is important in creating effective marketing materials. If, on the basis of value expectations and market option assessments from Phase I, the family decides to move forward with testing the market, we then enter Phase II.

Phase II involves staging and organizing the relevant financial and operating data into a confidential information memorandum (CIM). The CIM is designed to tell the story of the business, expound on the merits of the business and its market position, and describe the seller’s preferred transaction structure. The CIM should provide enough information for prospective buyers to form an expression of interest (i.e. the initial offer). Of course, prior to receiving the CIM, prospective buyers must execute non-disclosure agreements, which are designed to protect the seller from having their confidential information revealed to unintended audiences.

Parallel with the preparation of the CIM, the financial advisor will create a list of prospective buyers. These prospective buyers often include a mix of competitive and/or friendly industry players, private equity investors, and family offices. Phase II may also involve conducting meet-and-greet exchanges with prospective buyers in order to negotiate and secure expressions of interest in the form of indications of interest (IOIs) or letters of intent (LOIs). After careful study of the offers, the financial advisor will help the selling shareholders select the preferred bid. Signing an IOI/LOI generally marks the end of Phase II.

Phase III By signing and IOI/LOI, the selling shareholder commits to dealing exclusively with that buyer. One of the first steps in Phase III is satisfying the buyer’s due diligence requirements. Parallel with this process, legal advisors to the buyer and the seller begin drafting the legal documents required to complete the transaction.

Phase III By signing and IOI/LOI, the selling shareholder commits to dealing exclusively with that buyer. One of the first steps in Phase III is satisfying the buyer’s due diligence requirements. Parallel with this process, legal advisors to the buyer and the seller begin drafting the legal documents required to complete the transaction.

It is important to understand that the negotiating process from Phase II carries forward until the deal is closed. Deal terms often contain various structural features including non-compete agreements, earn-out arrangements, equity roll-over provisions, escrow and holdback terms, working capital thresholds, real estate considerations, and other important make-or-break considerations. The terms of these side elements can represent a significant portion of total deal value and cannot be overlooked. The wording of the documents is part of the negotiating and deal monitoring process. The focus is making sure that the offer and all its terms are clearly captured in the actual transaction documents.

Assuming everything passes muster, closing occurs. But even then the transaction is not completely finished until the selling family receives all of the consideration promised in the deal. A portion (often 5% to 20%) of the total purchase price is usually held in escrow for 12 to 24 months after closing against potential claims of the buyer for violation of seller representations and warranties. The amount, duration, and conditions of escrow release are important elements of the legal documents governing the transaction. The significance of these terms points to the importance of remaining vigilant and engaged in the process to maximize the outcome.

We hope this quick tour of the selling process helps readers better understand the steps involved in selling the family business. Family shareholders and family business directors owe it to themselves and to their stakeholders to be aware of the liquidity options that may available in the expanding market for private companies.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director