The Case for Research and Development

A Case Study of Innovation and Taxes

No family business can be successful over generations without innovation. Consistent investment in research and development is at the heart of many family business breakthroughs. Like any investment, R&D spending consumes family capital today in the expectation of generating more cash flow in the future.

Research & development spending defies simple categorization.

- Economists generally view R&D spending as an investment akin to capital spending for a new piece of productive equipment. After all, companies spend money on research & development to realize benefits in the future, not right now.

- Accountants, on the other hand, are a skeptical breed, and they observe that many R&D projects never actually pay off. In other words, while the intent is to spend today in order to realize a benefit tomorrow, the only thing that is certain is the amount spent today. Unwilling to accept the risk of an uncertain payoff, accountants treat R&D costs as an unrecoverable expense of the period in which they were incurred.

For many years, tax law adopted the accountants’ perspective. Companies deducted R&D costs from taxable income as those dollars were spent. (The somewhat tortured history of the R&D tax credit is outside the scope of this post.)

As noted in a recent Wall Street Journal article, however, a little-heralded provision of the Tax Cut & Jobs Act of 2017 upended the status quo for tax treatment of R&D expenditures. Beginning in 2022, tax law adopts the economists’ perspective. Taxpayers are now required to capitalize R&D costs, deducting them from taxable income over a period of five years rather than in the period the costs were incurred.

R&D spending decisions are capital budgeting decisions. The after-tax R&D expenditures represent the initial “outflow” against which future expected “inflows” are weighed to assess whether the expected return is sufficient compensation for the corresponding risk. The higher the initial “outflow,” the higher the subsequent “inflows” must be to justify the expenditure.

In capital budgeting, timing matters. A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. A simple example will illustrate the effect of tax deduction timing on a family business’s willingness to undertake an R&D project.

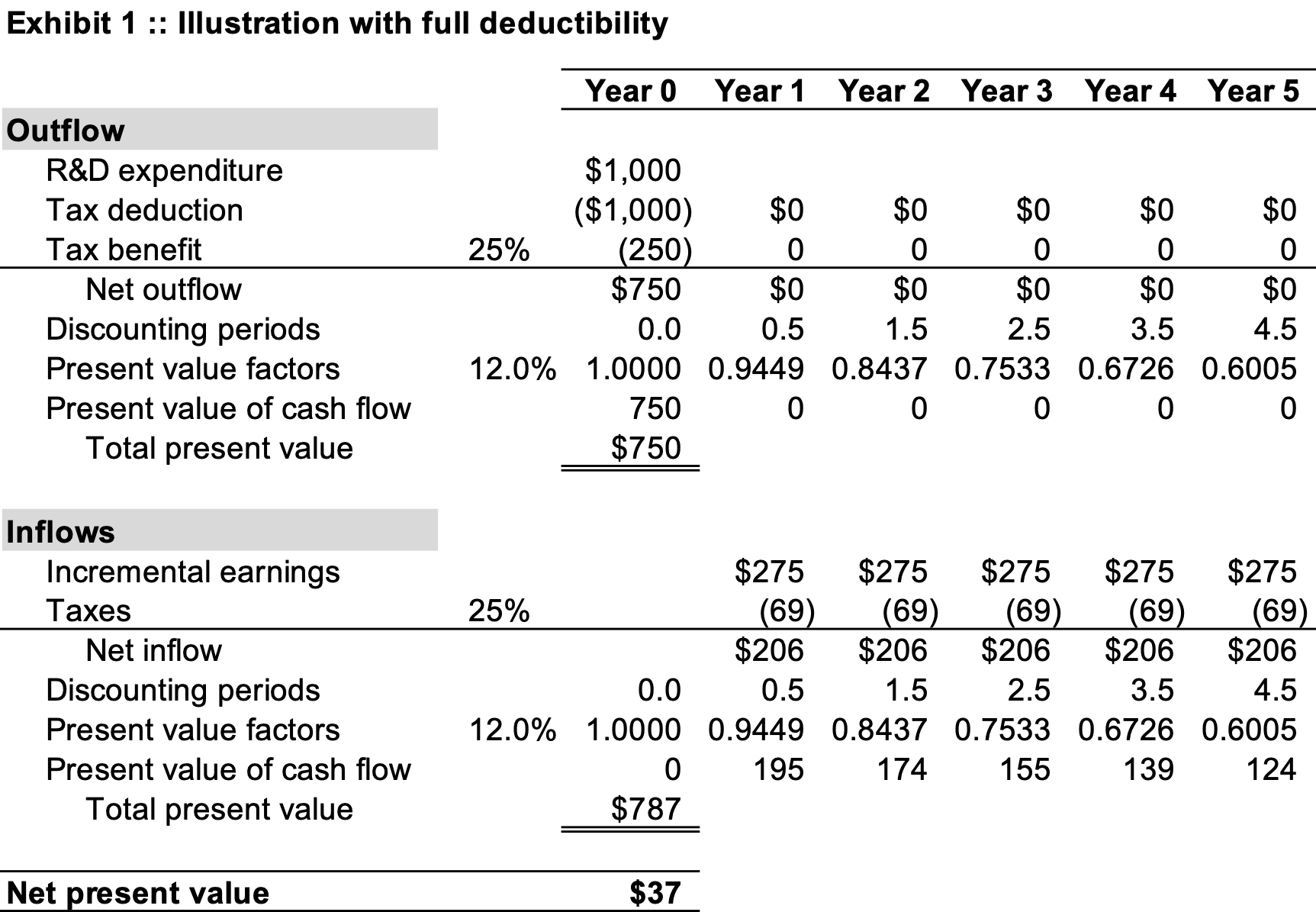

Exhibit 1 presents the net present value analysis for an R&D project that requires an immediate expenditure of $1,000 and is expected to generate annual pre-tax income of $275 for five years.

Assuming a discount rate of 12%, the proposed project has a positive net present value of $37, which indicates that undertaking the project will be accretive to the value of the family business. The present value of the required cash outflow is reduced by the tax benefit attributable to deducting the full R&D costs.

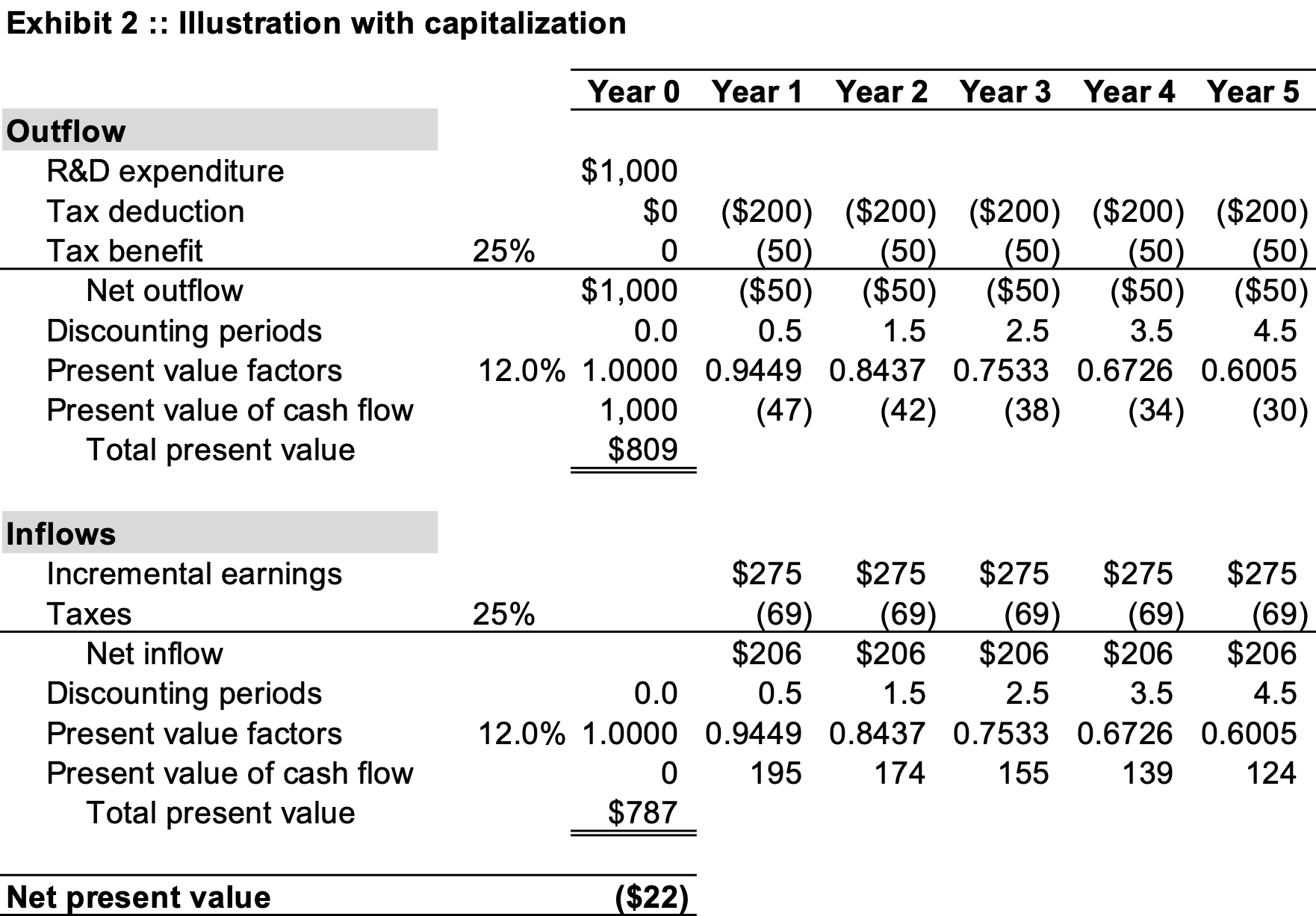

Exhibit 2 illustrates the impact of R&D capitalization on the project’s financial feasibility.

The present value of the cash inflows is unaffected; however, the deferral of tax benefits from deductibility increases the present value of the after-tax cash outflow. As a result, the net present value turns negative, indicating that the project would detract from the value of the family business.

In this simple example, the required capitalization of R&D spending caused the net present value to go negative. The economics of real projects are rarely so transparent. Nonetheless, the point is that capitalizing R&D expenditures for tax purposes detracts from the financial feasibility of proposed R&D projects.

The WSJ article included comments from the CFO of public company Hyster-Yale (ticker HY) on the cash flow implications of capitalizing R&D expenditures: “…less that I have to invest back into my business, whether it’s R&D, whether it’s plants and equipment, hiring new people…” Reported R&D spending at Hyster-Yale confirms the impact on marginal investing decisions. As a percentage of revenue, R&D spending at Hyster-Yale was 2.8% and 2.9% in 2022 and 2023, respectively, compared to an average of 3.6% for the preceding five years, as shown in Exhibit 3.

At the margin, the change in tax treatment for research & development expenditures clearly had an impact on decisions at Hyster-Yale.

What about Your Family Business?

Innovation is critical to sustainability for family businesses but requires investment. We close this post with a few questions for you and your fellow directors to ponder.

- What is the role of innovation in your family business?

- How do you identify potential investments that would spur innovation?

- Do you have a disciplined process for evaluating potential innovation investments?

- Do you have a disciplined process for assessing whether prior innovation investments have paid off?

- Have you defined an “Innovation Index” (usually expressed as a percentage of annual revenue derived from new products) for your family business? If so, do you have a defined target for that measure?

- Do your tax, financial planning & analysis, and R&D staff communicate and collaborate on vetting R&D projects?

While it is tempting for family businesses to look back fondly at past successes, those focused on sustainability look forward and allocate resources to innovation to provide wins for the next generation. Give one of our professionals a call to discuss your spending and investing decisions in confidence.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director