These Loafers Are Made for Walkin’

Italian Shoemaker, Tod's, Opts Out of the Public Markets

Last week, Tod’s – the Italian maker of luxury shoes – announced plans by the founding Della Valle family to take the company private. Under the proposed transaction, the Della Valle family would invest €338 million to increase its ownership interest from just under 65% to 90%. Following the transaction, the remaining 10% equity position will be held by luxury conglomerate LVMH.

The proposed purchase price of €40 per share represents a 21% premium relative to the pre-announcement trading price for the shares of about €33 per share.

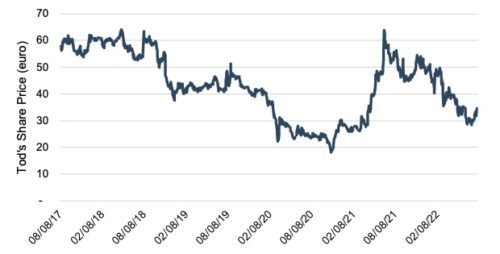

From a pandemic low of approximately €18, Tod’s share price peaked at approximately €64 per share in June 2021, from which level shares have fallen steadily to the €30 to €35 range preceding the going private announcement.

Motivation For Transaction

Having been a public company for more than twenty years, what is the family’s motivation for taking the company private now? According to the Wall Street Journal, the Della Valle family is taking the company private to “accelerate its development” and “free the company of ‘limitations’” resulting from its public status. The plan to “accelerate” development is interesting, given that it seems like the most common reason companies cite for going public is to improve access to capital to “accelerate” company growth.

Most family businesses will never have to think about whether to list their shares on a public exchange, much less – having done so – to reverse course and take the family business private again. Nonetheless, we believe Tod’s transaction highlights two obligations of all family businesses, whether publicly listed or not. The first is the imperative to perform, and the second is the responsibility to report.

The Imperative to Perform

The stock price chart presented above is uninspiring. Over the past five years (prior to announcing the going private transaction), Tod’s shares had shed approximately 50% of their value. In contrast, the shares of luxury conglomerate LVMH tripled in value over the same period, from €233 to €691 per share, while shares of Gucci parent Kering nearly doubled (from €313 to €553).

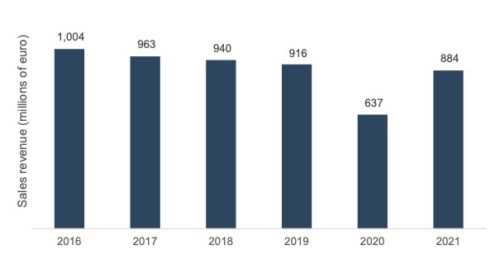

A quick look at the income statement for Tod’s confirms that the underperformance of the shares mirrored underperformance operationally. Since acquiring the Roger Vivier brand in 2016, annual revenue at Tod’s has fallen at a 2.5% annual clip.

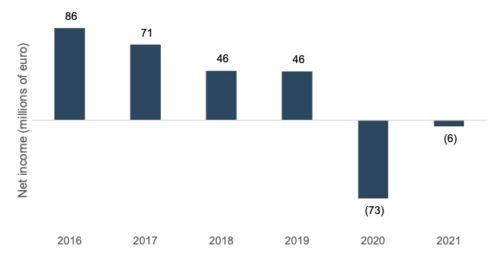

Earnings have suffered as well, with the company reporting net losses in 2020 and 2021.

The losses in 2020 and 2021 forced the company to discontinue dividend payments, which had already fallen with earnings from €2 per share in 2016 to €1 per share in 2019.

In short, the company failed to deliver value to its shareholders, and the financial performance suggests that it may have been strategically adrift. Following the €400 million acquisition of the Roger Vivier brand (from a related party, no less), Tod’s invested approximately €220 million in capital expenditures and one small acquisition during the five years ended 2021 (less than 5% of revenue). Against a backdrop of weakening organic performance, the company had dwindling resources for significant capital investment to spur growth.

Not being accountable to public investors frees family business leaders to consider a broader range of performance objectives other than profit alone. However, being privately-held does not free family business directors from the imperative to perform. Any non-financial goal to which a family may aspire, no matter how noble or laudable, is ultimately supported and underwritten by growing, profitable core business operations. One task of a director is to consider how best to allocate the family’s capital resources to earn a competitive return on capital.

Being privately-held does not free family business directors from the imperative to perform

Family shareholders may not have the flexibility of public investors in the short term, but in the long-term family capital will flow toward its highest and best use. Chronic underperformance will cause the highest and best use to be found outside the family business, which will likely undermine many of the non-financial goals and objectives of the family, often to the detriment of employees, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders.

We can’t quite envision how taking Tod’s private will “accelerate” its growth. That said, the family has recognized that the current trajectory is not sustainable and is attempting to address the company’s underperformance. Are you and your fellow directors holding yourselves accountable for generating sustainable competitive returns on capital for your family shareholders?

The Responsibility to Report

The second obligation is the responsibility to report. While the “limitations” of being a public company prompting the transaction were not enumerated, the burden of reporting results to public shareholders is time-consuming and sometimes requires companies to disclose what they believe is competitively sensitive information. While public companies in Europe are not on the quarterly reporting cycle faced by SEC registrants in the U.S., the annual (and semi-annual) reports of European companies are far more detailed than those of their U.S. counterparts, as you can see here.

Having read through the most recent annual report, it is not hard to see why Tod’s management would be eager to get out from underneath that reporting burden. Privately-held family businesses save a lot of time and money by not being subject to onerous financial reporting obligations. However, that does not mean that shareholder reporting is not important for family businesses. In reality, shareholder reporting is more important for family businesses than public companies. After all, public companies are reporting their results and strategy to anonymous strangers and institutional investors, while family businesses report their results to grandparents, parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

In our experience, many family businesses ignore the benefits of being intentional and strategic about how they report financial results to family shareholders. They do so at their own peril. Uninformed family shareholders eventually become suspicious family shareholders. And suspicious family shareholders often become disgruntled – or, even worse – litigious family shareholders.

Uninformed family shareholders eventually become suspicious family shareholders

Family business directors are stewards of the family’s wealth, and reporting is a fundamental obligation of stewards. No, it is not necessary to prepare SEC-worthy quarterly reports for your family shareholders. But that does not give directors license to ignore shareholders. Rather, it gives family business leaders the flexibility to report what family shareholders need to know, with the appropriate frequency and in the most relevant format. Any time and resources saved by shirking this responsibility will pale in comparison to the costs and distraction of dealing with suspicious and unengaged family shareholders.

We will return to the topic of shareholder reporting for family businesses in a future post. In the meantime, check out our whitepaper on communicating financial results to family shareholders, which you can download here.

Family Business Director

Family Business Director