The most common valuation-related family business disputes we see in our practice relate to measuring value for buy-sell agreements. Far too often, buy-sell agreements include valuation provisions that appear designed to promote strife, incur needless expense, and increase the likelihood of intra-family litigation.

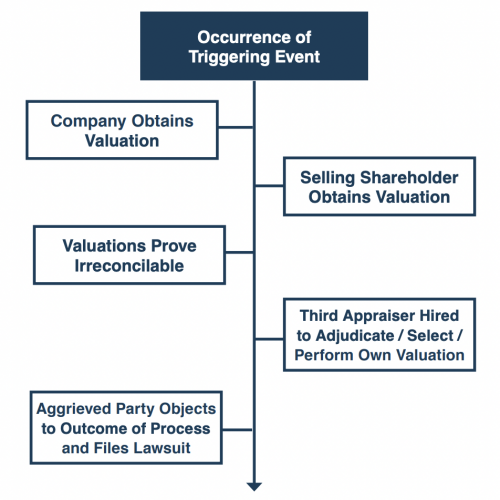

The ubiquity of valuation provisions in buy-sell agreements that do not work is striking. While there are many variations on the theme, the exhibit below illustrates the broad outline of the valuation processes common to many buy-sell agreements.

The buy-sell agreement presumably exists to avoid litigation, but the valuation processes in most agreements seem to increase, rather than decrease, the likelihood of litigation. It is almost as if failure is a built-in design feature of many plans.

Top Five Causes of Valuation Process Failure

- Ambiguous (or absent) level of value. As we discussed at length in section 3 of the What Family Business Advisors Need to Know About Valuation whitepaper, family businesses have more than one value. There is no “right” level of value for a buy-sell agreement, so the agreement must specify very clearly which level of value is desired. Failing to specify the level of value, and just assuming that the eventual appraiser will know what the parties intended is a recipe for disaster. The difference between the pro rata value of the family business to a strategic control buyer and the value of a single illiquid minority share in the family business can be large. Yet too many buy-sell agreements simply say that the appraisers will determine the “value” or “fair market value” of the shares. That is not good enough.

- Information asymmetries. Most buy-sell agreements have no mechanisms for ensuring that the appraiser for the selling shareholder has access to the same information regarding historical financial performance, operating metrics, plans, and forecasted financial performance as the appraiser retained by the family business. The resulting asymmetries give both sides a ready-made excuse to cry foul when the valuation results do not meet their expectations. We recommend a thoroughly documented process of simultaneous information sharing, joint management interviews, and cross-review of valuation drafts to eliminate the likelihood of information asymmetries derailing the transaction.

- Lack of valuation standards / appraiser qualifications. It is not hard to find an investment banker, business broker, or other industry insider who probably has a well-informed idea of what the family business might be worth (particularly in the context of a sale to a strategic buyer). However, when executing the valuation provisions of a buy-sell agreement, it is crucial to specify the qualifications for the appraisers. While an opinion of value from a business broker might be suitable for some purposes, the scrutiny that is attached to a buy-sell transaction can best be withstood by an appraiser who is accountable to a recognized set of professional standards that set forth analytical procedures to be followed and reporting guidelines for communicating the results of their analysis. There are multiple reputable credentialing bodies for business appraisers that promulgate quality standards for their members. The buy-sell agreement should specify which professional credentials are required to serve as an appraiser for either the selling shareholder or the company.

- Unrealistic timetable / budget. Families often share a well-founded fear that the valuation process will prove interminable without specified deadlines. Deadlines are important but must be realistic. If there is ever a time for a “measure twice, cut once” mentality, it is in buy-sell transactions. Due diligence and analysis takes time, and the schedule set forth in the buy-sell agreement needs to take into account the inevitable “dead time” during which appraisers are being interviewed and retained, information is being collected, and diligence meetings are being scheduled. The same goes for budget: if you think a quality appraisal is expensive, see how costly it is to get a cheap one. Provisions that identify which parties will bear the cost of the appraisal can help incentivize the parties to reach a reasonable resolution, but can also be so punitive that they discourage shareholders from pursuing what is rightfully theirs. Each family should carefully evaluate what system will work best for their circumstances.

- Advocative valuation conclusions. Sadly, even when the level of value is clearly defined, information asymmetries are eliminated, valuation standards are specified, and the timetable and budget is reasonable, the two appraisers may still reach strikingly different valuation conclusions. Whether this is a result of genuine difference of (informed) opinion or bald advocacy is hard to say, but it is rare for the appraiser for the selling shareholder to conclude a lower value than that of the appraiser for the company. Valuation is a range concept, so it should ultimately not be too surprising when appraisers don’t agree. Yet that inevitable disagreement adds time and cost to many buy-sell valuation processes.

Is There a Better Way?

Given the challenges and pitfalls described above, is there any hope that a valuation process for a buy-sell agreement can reliably lead to reasonable resolutions? We think so. We have identified three steps that we recommend for clients to help make their buy-sell agreements work better.

- Make sure that the buy-sell agreement provides unambiguous guidance to all parties as to the level of value and qualifications of the appraiser.

- Retain an appraiser to value the company now, before a triggering event occurs. This is essential for two reasons. First, it transforms the “words on the page” into an actual document that shareholders can review and question. No matter how carefully one defines what an appraisal is supposed to do, the shareholders are likely to have different ideas about what the output will actually look like. This appraisal report should be widely circulated among the shareholders, so they have an opportunity to familiarize themselves with how the company is appraised. Second, performing the valuation before a triggering event occurs increases the likelihood that the family shareholders can build consensus around what a reasonable valuation looks like. People tend to take a more sane view of things when they don’t know if they will be the buyer or the seller.

- Update the valuation periodically. Simply put, static valuation formulas don’t work in a changing world. Periodic updates to the valuation help the valuation process become more efficient, and help all shareholders keep reasonable expectations about the outcome in the event of an actual triggering event. Discontent and strife are more likely to be the product of unmet expectations rather than the absolute valuation outcome. Periodic valuations help to set expectations and reduce the likelihood of friction. Following these three steps are essential to increasing the likelihood that the valuation process in a buy-sell agreement will actually work and will help keep the family out of the courtroom, where both sides to the dispute often walk away losers.

This week's post is an excerpt from the whitepaper, What Family Business Advisors Need to Know About Valuation. If you would like to read the full version click here.