How RIAs Should Use Their Excess Horsepower

Making Productive Use of Earnings

From zero to Aisle 4 in seconds: the Mercedes AMG 53 wagon (image via Chat GPT).

Key Takeaways

- Intentionality matters: The real challenge for investment management firms isn’t generating earnings — it’s deciding what to do with them once success creates excess capital.

- Match capital use to strategy: Whether a firm favors growth or stability, capital deployment should align with its business model, stakeholder priorities, and long-term vision.

- Balance risk and return: A structured framework helps leadership evaluate options — from holding cash to reinvestment and acquisitions — through a risk-adjusted lens.

Horsepower and Intentionality: Making Productive Use of RIA Earnings

A Mercedes-AMG E53 or Audi RS6 Avant is one of the great contradictions of modern engineering: a family wagon with more than 500 horsepower. These cars can out-accelerate supercars but mostly idle in school-zone traffic and grocery-store parking lots. All that potential—barely used.

Many investment management firms are built the same way. They possess far more earnings-generating horsepower than is necessary to keep daily operations running smoothly, provide reasonable shareholder returns, and fund organic growth. Independent trust companies and RIAs are inherently capital-efficient, balance-sheet-light enterprises. Once a firm achieves scale, profits often accumulate faster than leadership knows what to do with them.

The challenge isn’t generating earnings—it’s deciding how to put them to use.

The Nature of RIA Earnings

Before I go any further, I’ll start by distinguishing earnings from compensation. Compensation represents fair, market-based pay for the people who run the business. Earnings are what remain—the residual return to ownership after all contributors are paid.

The line between earnings and compensation is admittedly murky

The line between earnings and compensation is admittedly murky in the owner-operator world of investment management, but when I talk about earnings, I mean a measure of profits after the ownership is paid a market return for their labor contribution to the enterprise.

RIAs and trust companies, unlike manufacturing or tech firms, don’t need continual capital investment in plants or platforms. That’s part of what makes them so valuable. But it also means excess capital can quietly pile up on the balance sheet or be misdirected to poor opportunities.

At some point, leadership has to decide whether their accumulation or deployment of cash earnings represents prudence or inertia. The question is less about accounting than about governance and intent.

The Menu of Capital Uses

Firms generally face five broad options for deploying retained earnings:

- Retain for Resilience. Building a cash reserve supports stability, cushions volatility, and preserves independence.

- Distribute to Owners. Regular dividends or distributions reward investors and reinforce accountability for results.

- Repurchase or Redeem Shares. Buybacks or redemptions can manage ownership transitions and create liquidity for retiring partners.

- Reinvest in the Business. Funding business development, technology, marketing, or staff training fuels organic growth.

- Pursue Strategic Acquisitions. Buying complementary businesses can expand reach or capability when the fit and economics are right.

Early-stage firms often prioritize retention to build staying power. Mature firms may emphasize distributions once scale and stability are secure. The right mix depends on the firm’s stage of development, risk tolerance, and strategic aims. What matters is that decisions are made intentionally, and not by default.

Evaluating the Trade-Offs: Risk and Return in Capital Allocation

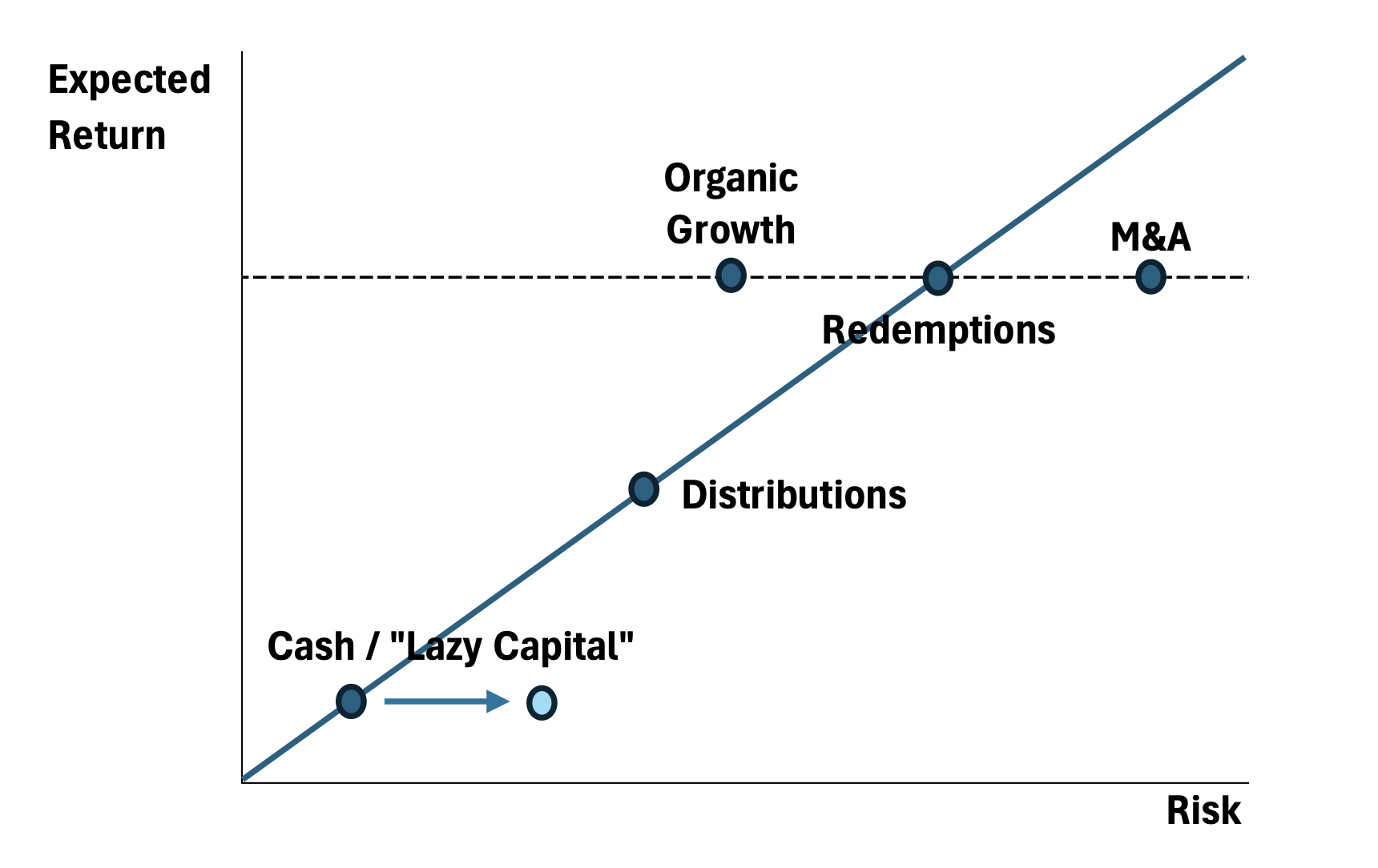

Each use of capital carries its own risk-return profile—just like any investment decision. The goal is not to chase the highest nominal yield, but to identify the most efficient balance of risk and return consistent with the firm’s temperament and mission.

Figure 1. Risk and Return of Capital Allocation Options

Retained cash carries little operational risk, but too much of it can become “lazy capital,” diluting enterprise returns with low-yielding, non-operating assets. Worse, surplus cash can invite complacency or risk-taking behaviors that undermine discipline.

Distributions are a direct return to shareholders and can, in theory, be reinvested elsewhere in assets with lower aggregate risk than remaining in the business. Redemptions behave similarly in financial theory, though in practice they create asymmetry—one owner’s liquidity is another’s risk.

Organic reinvestment (marketing, technology, or training) typically delivers enterprise-level returns with manageable execution risk and discrete costs. M&A, by contrast, can produce transformational gains but carries greater asymmetry of information and post-closing surprises. On a risk-adjusted basis, it’s a bet that an opportunity is worth more to the buyer than to the seller. Sometimes it is.

The point isn’t prescription—it’s perspective. Every capital decision has a measurable trade-off.

The Discipline of Intentionality

Capital allocation is strategy in numerical form

Capital allocation is strategy in numerical form. The test of leadership is not whether earnings are paid out, reinvested, or spent on acquisitions, but whether those actions support the firm’s business model, strategic focus, and stakeholder priorities.

For many firms—particularly those emphasizing stability for clients and employees—it may be wise to tilt toward earnings retention and consistent distributions. Predictability breeds confidence and helps preserve the culture that clients and staff value. Other firms, especially those pursuing expansion, may find greater long-term benefit in reinvesting capital in technology, people, or acquisitions.

There’s no universal formula. What matters is that choices are intentional, proportional, and aligned with what defines the firm’s success. Idle cash or reflexive habits (“we’ve always paid out 60%”) are not strategies—they’re defaults. The most disciplined firms adopt a capital-allocation framework that:

- Establishes payout and reserve targets suited to the firm’s purpose and lifecycle.

- Revisits those targets regularly as markets and opportunities evolve.

- Communicates the rationale clearly to shareholders and staff.

Intentionality isn’t about maximizing growth or distributions—it’s about using the firm’s financial horsepower to reinforce and support the mission.

Keeping it on the Road

Most high-powered grocery-getters like the one pictured above are never going to be track-tested, and that’s a pity. But it would be a far greater pity to take the remarkable earnings-generating capacity of a well-run investment management firm and squander it on poor choices—or worse on an unwillingness to make choices at all.

The best firms don’t merely build power; they learn to deploy it with purpose. In both cars and capital, performance without intention is just wasted potential.

About Mercer Capital

Mercer Capital is a valuation and financial advisory firm organized by industry specialization. Our Investment Management Team provides valuation, transaction, litigation, and consulting services to a client base that includes asset managers, wealth managers, independent trust companies, broker-dealers, private equity firms, and alternative asset managers.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights