Family business owners cite different motives for investing their time, energy, and savings to build successful businesses. Some have entrepreneurial zeal, while others are creators who see problems in the world that they can solve. Others are natural leaders who are inspired by the job opportunities and other “positive externalities” that successful enterprises generate for employees and the communities in which they operate. But common to nearly all family business owners is the desire to provide financially for their heirs. As a result, one of the most common concerns such owners cite is the ability to transfer ownership of the family business to the next generation in the most tax-efficient way.

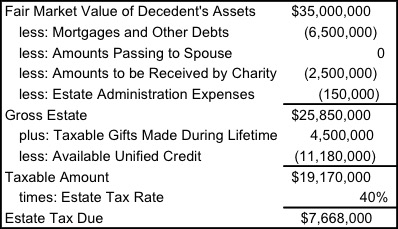

The Internal Revenue Service defines the estate tax as follows: “The estate tax is a tax on your right to transfer property at your death.” The amount of tax is calculated with reference to the decedent’s gross estate, which is the sum of the fair market value of the decedent’s assets less certain deductions for mortgages/debts, the value of property passing to a spouse or charity, and the costs of administering the estate.

As with all taxes, things are not as simple as they seem. Before calculating the estate tax due, two adjustments are made. First, all taxable gifts previously made by the decedent (and therefore no longer in the estate) are added to the gross estate. Second, the sum of the gross estate and prior taxable gifts is reduced by the available unified credit. The unified credit for 2018 is just over $11 million. The following table illustrates the calculations for the taxable estate of an unmarried individual.

To complicate things a bit further, estates have benefited from the introduction of “portability” to the estate tax regime in 2011. Portability refers to the ability of an individual to transfer the unused portion of their available unified credit to a surviving spouse. The ultimate effect of portability is that for married family business owners, the total available unified credit is slightly more than $22 million.

Taxes are never fun, but what proves to be especially vexing about the estate tax for family business owners is that a substantial portion of their estate often consists of illiquid interests in private company stock. Going back for a moment to our prior example, if the decedent’s assets consist primarily of a portfolio of marketable securities, it is relatively easy to liquidate a portion of the portfolio to fund payment of the tax. If, on the other hand, the decedent’s assets are primarily in the form of shares in the family business, liquidating assets to pay the estate tax may prove more difficult (estate taxes are payable in cash and may not be paid in-kind with family business shares). As a result, family businesses may be sold or be forced to borrow money to fund payment of a decedent’s estate tax liability.

Attorneys who specialize in estate taxes have devised numerous strategies for helping families manage estate tax obligations. Strategies range from relatively simple, such as a program of regular gifts to family members, to complex, such as the use of specialized trusts. While the finer points of various potential strategies is beyond the scope of this post, the concept of fair market value is essential to understanding and evaluating any estate planning strategy.

What is Fair Market Value?

As noted above, fair market value is the standard of value for measuring the decedent’s estate, and therefore, the estate tax due. The IRS’s estate tax regulations define fair market value as “the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.”

So far, so good.

But how does all this work for a family business? To understand the underlying rationale for much estate planning, we need to explore how the standard of value intersects with what is referred to as the level of value. In other words, the fair market value of family business shares in an estate depends not just on the fundamentals of the business (expected future revenues, profits, investment needs, risk, etc.) but also on the relevant level of value.

If an estate owns a controlling interest in a family business (in most cases, more than 50% of the stock), the fair market value of those shares will reflect the estate’s ability to sell the business to a competitor, supplier, customer, or financially-motivated buyer such as a private equity fund. In contrast, the owner of a small minority block of the outstanding shares of a family business has no ability to force the business to change strategy, seek a sale of the business, or otherwise unilaterally compel any action. As a result, the owner of the shares is limited to waiting until the shareholders that do have control decide to sell the business or redeem the minority investor’s shares. In the meantime, they wait (and, potentially, collect dividends). If there is a willing buyer for the shares, they may elect to sell, but that buyer will be subject to the same illiquidity, holding period risks, and uncertainties, so the price is unlikely to be attractive.

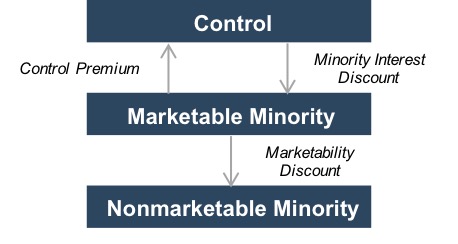

Business appraisers often describe the levels of value with reference to a chart like the following:

The levels of value chart captures two essentially common-sense notions regarding value. First, investors prefer to have control rather than not. The degree to which control is valuable will depend on a whole host of case-specific facts and circumstances, but in general, having control is preferred. Second, investors prefer liquidity to illiquidity. Again, the magnitude of the appropriate marketability discount will depend on specific factors, but not surprisingly, investors prefer to have a ready market for their shares. Fair market value is measured with respect to both of these common-sense notions.

Estate Planning Objectives

As a result, one objective of most estate planning techniques is to ensure – through whatever particular mechanism – that no individual owns a controlling interest in the family business at his or her death. Of course, minimizing taxes is only one possible objective of an estate planning process, which might include asset protection, business continuity, and providing for loved ones.

Therefore, family businesses should carefully consider whether an estate planning strategy designed to minimize estate taxes will have any unintended negative consequences for the business or the family.

- For example, an aggressive gifting program that causes the founder to relinquish control prematurely may increase the likelihood of intra-family strife, or jeopardize the family’s ability to make timely strategic decisions on behalf of the business.

- Or, adoption of an unusually restrictive redemption policy in an effort to minimize the fair market value of minority shares in the company may lead to inequitable outcomes for family members having a legitimate need to sell shares.

In short, families should be careful not to let the tax tail wag the business dog. Families should consult legal, accounting, and valuation advisors who understand their business needs, family dynamics, and objectives to ensure that their estate plan accomplishes the desired goals.