One of the greatest sources of strife in family businesses is ill-defined roles.

- What does a good shareholder do?

- What is expected of a family business board member?

- How will the performance of management be evaluated?

Management accountability is hard for any company; effective management accountability within a complex web of family relationships can be an order of magnitude more difficult. Since some family members may fill multiple roles, clear and appropriate expectations paired with measurable outcomes are foundational to a management accountability structure that promotes business sustainability and family cohesion.

Who Sets Expectations?

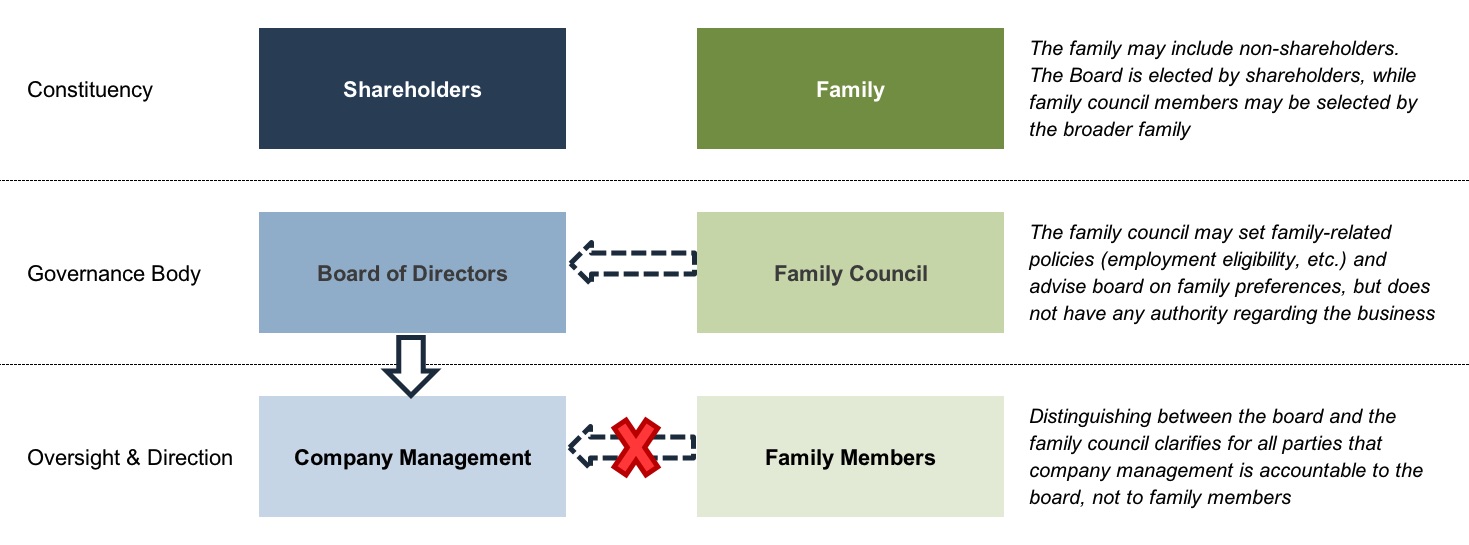

Management accountability is an element of overall corporate governance. In family businesses, corporate governance and family governance can sometimes be hard to separate, but working to distinguish between the two pays dividends for both the business and the family.

The first step for many families in developing more formal governance is moving strategic business deliberations from the dining room to the board room. In the first generation, it is common for the board to consist only of mom and dad. As the business matures, the natural result of such arrangements is that the board meets continually, but never effectively. What works for the bootstrapping startup does not work for the established multi-generation family business. Formalizing the board governance process may be as simple as scheduling regular meetings, establishing appropriate sub-committees, and preparing real agendas which are distributed to members in advance of meetings. The addition of one or more independent directors may be appropriate for some companies. Independent directors with industry expertise and relevant experience can provide fresh perspective to deliberations and model how to provide frank feedback unencumbered by family baggage. The appointment of independent directors also signals that the board’s job is company oversight, not to serve as the final arbiter for non-business family disputes.

A second common step is to establish a family council. While all family councils are unique, the principal role of the family council is to provide a forum for group decision-making on non-business family matters. Many family councils also provide opportunities for education regarding the business and collect input from family members about business decisions including distribution policy, capital structure, and capital budgeting (i.e., reinvestment). This input is valuable to the board, but is not binding; the board has sole responsibility for business oversight.

A parallel governance structure like that illustrated above helps to clarify that management (whether comprising family members or non-family professionals) is accountable to the board of directors, who in turn owes a fiduciary duty to the shareholders. As a result, the board of directors has the authority and responsibility to establish expectations for management, assess performance, and determine whether remedial actions are appropriate. In other words, the CEO is accountable to the board of directors and not her obstreperous second cousin.

How Should Expectations Be Set?

One reason successful family businesses remain privately-held is that such businesses can more easily avoid the “short-termism” perceived to afflict public markets, where success or failure might judged by next quarter’s earnings release. Since family businesses are free from the constraints of the quarterly reporting treadmill, management expectations should reflect the long-term goals that will promote the sustainability of the business and the financial success of the family.

Developing a so-called “balanced scorecard” to evaluate management performance can help promote a long-term perspective that aligns management accountability with the overall health of the company. As developed by Professor Robert Kaplan of the Harvard Business School, a balanced scorecard can help to promote management accountability by focusing on four key elements of business success.

- Customer perspective: How do customers see the business?

- Internal business perspective: What must the business excel at?

- Innovation and learning perspective: Can the business continue to improve and create value?

- Financial perspective: How does the business look to shareholders?

Notice that the financial perspective is only one component of the balanced scorecard. To be sure, if management succeeds with regard to the other perspectives, financial success should follow. The idea is to take a broader view of corporate health, balancing traditional financial metrics with a few measurable operating metrics that will reveal whether the company is engaging in the activities that will promote the long-term sustainability (and financial performance) of the business.

The essence of a balanced scorecard – or any other management accountability tool – is pairing observable measures with business-specific goals under each perspective. Metrics that are not correlated to the company’s strategies won’t get traction, and goals that can’t be measured won’t be achieved. To be useful as a management accountability tool, the selected metrics should describe processes or outcomes over which management has at least some degree of control. For example, revenue per day of operation and number of rainout days are both measures that contribute to the financial success of a theme park, but only one is subject to management influence.

Making Accountability Work

Managing the family business is not a birthright, nor is it a responsibility that must be borne simply because of one’s birth. It is a job, and the associated compensation and financial incentives should reflect market conditions. The hardest part of a management accountability system is deciding what to do when clearly-communicated goals are not met. An ill-conceived accountability framework that does not have the support of all the major stakeholders can – in the end – create more problems than it solves.

Goals may fail to be met for multiple reasons:

- The goal was unrealistic. In retrospect, it may be obvious that no management team could have delivered the specified results.

- Management performed unsatisfactorily. Given the available resources and prevailing market conditions, management simply failed to meet expectations.

- Market or other forces outside of management’s control negatively affected the business. Going back to our prior example, the theme park may have suffered through an abnormally rainy summer.

- The business strategy proved to be ineffective and needs to be revised. Management has executed the plan flawlessly, but the plan did not accurately reflect the customer, supplier, technological, or competitive forces shaping the industry.

The reasons for failure are not always easy to discern. If the goals were unrealistic, management accountability should look different than if management performed unsatisfactorily. If the business strategy proved to be ineffective, who was responsible for developing the strategy? If the board supported, or perhaps even mandated, the strategy, to what degree should management be accountable for its failure? Evaluating management performance requires both strong nerves and the ability be flexible when warranted. A seasoned, independent outside voice on the board can be especially valuable when poor performance needs to be evaluated.

Conclusion

Management accountability in family businesses is hard. Overlooking the failures of a favored relative and magnifying minor faults because of a strained family relationship are both ever-present temptations. In the end, management is accountable to the board of directors, not the family at large. Management performance should be evaluated relative to a set of clearly-defined and measurable objectives that further the long-term health and sustainability of the company. Evaluating management performance when goals are not met is difficult, but failing to evaluate performance (and thereby letting problems fester) is not a responsible course of action.