The issue of a premium for an S corporation at the enterprise level has been tried in a tax case, and the conclusion is none.

In Kress v. United States (James F. Kress and Julie Ann Kress v. U.S., Case No. 16-C-795, U.S. District Court, E.D. Wisconsin, March 25, 2019), the Kresses filed suit in Federal District Court (Eastern District of Wisconsin) for a refund after paying taxes on gifts of minority positions in a family-owned company. The original appraiser tax-affected the earnings of the S corporation in appraisals filed as of December 31, 2006, 2007, and 2008. The court concluded that fair market value was as filed with the exception of a very modest decrease in the original appraiser’s discounts for lack of marketability (DLOMs).

Background on GBP

The company was GBP (Green Bay Packaging Inc.), a family-owned S corporation with headquarters in Green Bay, Wisconsin. The company experienced substantial growth after its founding in 1933 by George Kress. A current description of the company, consistent with information in the Kress decision, follows.

Green Bay Packaging Inc. is a privately owned, diversified paper and packaging manufacturer. Founded in 1933, this Green Bay WI based company has over 3,400 employees and 32 manufacturing locations, operating in 15 states that serve the corrugated container, folding carton, and coated label markets.

Little actual financial data is provided in the decision, but GBP is a large, family-owned business. Facts provided include:

- Although GBP has the size to be a public company, it has remained a family-owned business as envisioned by its founder.

- About 90% of the shares are held by members of the Kress family (a Kress descendant is the current CEO), with the remaining 10% owned by employees and directors.

- The company paid annual dividends (distributions) ranging from $15.6 million to $74.5 million per year between 1990 and 2009. While historical profitability information is not available, the distribution history suggests that the company has been profitable.

- Net sales increased during the period 2002 to 2008.

Hoovers provides the following (current) information, along with a sales estimate of $1.3 billion:

Green Bay Packaging is the other Green Bay packers’ enterprise. The diversified yet integrated paperboard packaging manufacturer operates through 30 locations. In addition to corrugated containers, the company makes pressure-sensitive label stock, folding cartons, recycled container board, white and kraft linerboards, and lumber products. Its Fiber Resources division in Arkansas manages more than 210,000 acres of company-owned timberland and produces lumber, woodchips, recycled paper, and wood fuel. Green Bay Packaging also offers fiber procurement, wastepaper brokerage, and paper-slitting services. (emphasis added)

The court’s decision states that the company’s balance sheet is strong. The company apparently owns some 210 thousand acres of timberland, which would be a substantial asset. GBP also has certain considerable non-operating assets including:

- Hanging Valley Investments (assets ranging from $65 – $77 million in the 2006 to 2008 time frame)

- Group life insurance policies with cash surrender values ranging from $142 million to $158 million during this relevant period and $86 million to $111 million net of corresponding liabilities

- Two private aircraft, which on average, were used about 50% for Kress family use and about 50% for business travel

GBP was a substantial company at the time of the gifts in 2006, 2007, and 2008. We have no information regarding what portion of the company the gifts represented, or how many shares were outstanding, so we cannot extrapolate from the minority values to an implied equity value.

The Gifts and the IRS Response

Plaintiffs James F. Kress and Julie Ann Kress gifted minority shares of GBP to their children and grandchildren at year-end 2006, 2007, and 2008. They each filed gift tax returns for tax years 2007, 2008 and 2009 basing the fair market value of the gifted shares on appraisals prepared in the ordinary course of business for the company and its shareholders. Based on these appraisals, plaintiffs each paid $1.2 million in taxes on the gifted shares, for a combined total tax of $2.4 million. We will examine the appraised values below.

The IRS challenged the gifting valuations in late 2010. Nearly four years later, in August 2014, the IRS sent Statutory Notices of Deficiency to the plaintiffs based on per share values about double those of the original appraisals (see below). Plaintiffs paid (in addition to taxes already paid) a total of $2.2 million in gift tax deficiencies and accrued interest in December 2014. It is nice to have liquidity.

Plaintiffs then filed amended gift tax returns for the relevant years seeking a refund for the additional taxes and interest. With no response from the IRS, Plaintiffs initiated the lawsuit in Federal District Court to recover the gift tax and interest they were assessed. A trial on the matter was held on August 3-4, 2017.

The Appraisers

The first appraiser was John Emory of Emory & Co. LLC (since 1999) and formerly of Robert W. Baird & Co. I first met John in 1987 at an American Society of Appraisers conference in St. Thomas. He is a very experienced appraiser, and was the originator of the first pre-IPO studies. Emory had prepared annual valuation reports for GBP since 1999, and his appraisals were used by the plaintiffs for their gifts in 2006, 2007, and 2008.

The Emory appraisals had been prepared in the ordinary course of business for many years. They were relied upon both by shareholders like the plaintiffs as well as the company itself.

The next “appraiser” was the Internal Revenue Service, where someone apparently provided the numbers that were used in establishing the statutory deficiency amounts. The court’s decision provides no name.

The third appraiser was Francis X. Burns of Global Economics Group. He was retained by the IRS to provide its independent appraisal at trial. As will be seen, while his conclusions were a good deal higher than those of Emory (and Czaplinski below), they were substantially lower than the conclusions of the unknown IRS appraiser. The IRS went into court already giving up a substantial portion of their collected gift taxes and interest.

The fourth appraiser was hired by the plaintiffs, apparently to shore up an IRS criticism of the Emory appraisals. Nancy Czaplinski from Duff & Phelps also provided an expert report and testimony at trial. Emory’s report had been criticized because he employed only the market approach and did not use an income approach method directly. Czaplinski used both methods. It is not clear from the decision, but it is likely that Czaplinski was not informed regarding the conclusions in the Emory reports prior to her providing her conclusions to counsel for plaintiffs.

While the court did not agree with all aspects of the work of any of the appraisers, the appraisers were treated with respect in the opinion based on my review. That was refreshing.

The Court’s Approach

The court named all the appraisers, and began with an analysis of the Burns appraisals (for the IRS). In the end, after a thoughtful review, the court did not rely on the Burns appraisals in reaching its conclusion.

After reviewing the essential elements of the Burns appraisals, the court provided a similar analysis of the Emory appraisals. The court was impressed with Emory’s appraisals, and appeared to be influenced by the fact that the appraisals were done in the ordinary course of business for GBP and its shareholders. The court surely noticed that the IRS must have accepted the appraisals in the past since Emory had been providing these appraisals for many years. Other Kress family members had undoubtedly engaged in gifting transactions in prior years.

The court then reviewed the Czaplinski appraisal. While the court was light on criticisms of the Czaplinski appraisals, it preferred the methodologies and approaches in the Emory appraisals.

Interestingly, the entire analysis in the decision was conducted on a per share basis, so there was virtually no information about the actual size or performance or market capitalization of GBP in the opinion. We deal with the cards that are dealt.

Summary of the Court’s Discussion

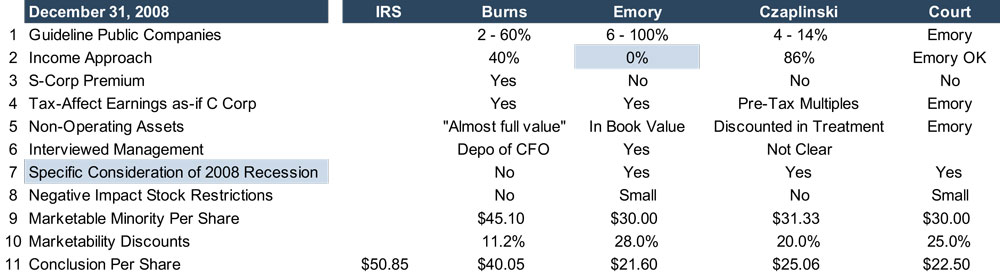

As I read the court’s decision, there were ten items that were important in all three appraisals, and an additional item that was important in the December 31, 2008 appraisal. Readers will remember the Great Recession of 2008. It was important to the court that the appraisers consider the impact of the recession on the outlook for 2009 and beyond in their appraisals for the December 31, 2008 date.

In the interest of time and space, we will focus on the appraisals as of December 31, 2008 in the following discussion. The summaries of the other appraisals are provided without comment at the end of this article. The December 31, 2008 summary follows. We deal with the eleven items that were discussed or implied in the subsections below.

There are six columns above. The first provides the issue summary statements. The next four columns show the court’s reporting regarding the eleven items found in the 2008 appraisal based on its review of the reports of the appraisers. Note that there is no detail whatsoever for the rationale underlying the IRS conclusion for the Statements of Deficiency. The final column provides the court’s conclusion. To the extent that items need to be discussed together, we will do so.

Items 1 and 2: The Market Approach and the Income Approach

All the appraisers employed the market approach in the appraisals as of December 31, 2008 (and at the other dates). They looked at the same basic pool of potential guideline companies but used different companies and a different number of companies in their respective appraisals.

The court was concerned that the use of only two comparable companies in the Burns report was inadequate to capture the dynamics of valuation. In fact, Burns used the same two guideline companies for all three appraisals, and the court felt that this selective use did not capture the impact of the 2008 recession on valuation (Item 7). He weighed the market approach at 60% and the income approach at 40% in all three appraisals.

Czaplinski used four comparable companies in her 2008 appraisal and weighted the market approach 14% (same in her other appraisals). Her income approach was weighted at 86%.

Emory used six guideline companies in the 2008 appraisal. While he used the market approach only, the court was impressed that “he incorporated concepts of the income approach into his overall analysis.” This comment was apparently addressing the IRS criticism that the Emory appraisals did not employ the income approach.

Items 3 and 4: The S-Corp Premium/Treatment

The case gets interesting at this point, and many readers and commentators will talk about its implications.

At the enterprise level, both Burns and Emory tax-affected GBP’s S corporation earnings as if it were a C corporation. This is notable for at least two reasons:

- Emory’s appraisals were prepared a decade or so ago. That was the treatment advocated by many appraisers at the time (and still), including me. See Chapter 10 in Business Valuation: An Integrated Theory, Second Edition, (Peabody Publishing, 2007) and the first edition published in 2004. The economic effect of treatment in the Emory appraisals was that there was no differential in value for GBP because of its S corporation status.

- The Burns appraisals also tax-affected GBP’s earnings as if it were a C corporation. This is significant because the IRS’ position in recent years has been that pass-through entity earnings (like S corporations) should not be tax-affected because they do not pay corporate level of taxes. Never mind that they do distribute sufficient earnings to their holders so they can pay their pass-through taxes. There was, therefore, no differential in GBP’s value because of tax-affecting.

The Czaplinski report avoided the S corp valuation differential issue by using pre-tax multiples (without tax-affecting, of course). Since the Czaplinski report used pre-tax multiples, there was no differential in value because of the company’s S corporation status.

The Burns report, however, did apply an S corporation premium to its capitalized earnings value of GBP. The decision reports neither the model used in the Burns report nor the amount of the premium. Let me speculate. The premium was likely based on the SEAM Model (see page 35 of linked material), published by Dan Van Vleet, who was also at Duff & Phelps at the time (like Czaplinski). I speculate this because it is the best known model of its kind.

If my speculation is correct, based on tax rates at the time and my understanding of the SEAM Model, it was likely in the range of 15% – 18% of equity value (100%), or a pretty hefty premium in the valuation. Nevertheless, Burns testified to the use of a specific S corporation premium at trial.

Again, if my speculation is correct, the facts that Czaplinski and Van Vleet were both from Duff & Phelps and that Czaplinki did not employ the SEAM Model likely provided for some colorful cross-examination for Czaplinki. If so, she seems to have survived well based on the court’s review.

The court accepted the tax-affected treatment of earnings of both Burns and Emory, and noted that Czaplinski’s treatment had dealt with the issue satisfactorily. The court did not accept the S corporation premium in the Burns report.

What do these conclusions regarding tax-affecting and no S corporation premium mean to appraisers and taxpayers?

- The court accepted tax-affecting of S corporation income on an as-if C corporation basis in appraising 100% of the equity of an S corporation. This is good news for those who have long believed that an S corporation, at the level of the enterprise, is worth no more than an otherwise identical C corporation. It should pour water on the IRS flame of arguing that there should be no tax-affecting “because pass-through entities do not pay corporate level taxes.”

- The court did not accept the specific S corporation premium advanced by Burns. This is a second recognition that there is no value differential between S and C corporations that are otherwise identical. After all, the election of S corporation status is a virtually costless event. The fact that the court considered testimony regarding an S corporation premium model and did not agree with its use is a very significant aspect of this case.

Kress v. U.S. will be quoted by many attorneys and appraisers as standing for the appropriateness of tax-affecting of pass-through entities and for the elimination of a specific premium in value for S corporation status.

Item 5: Non-Operating Assets

The treatment of non-operating assets by the appraisers is less than clear from the decision. What we know is the following regarding the substantial non-operating assets in the appraisals:

- The Burns report treated the non-operating assets at “almost full value.” This treatment was disregarded by the court.

- The Emory report did not provide for separate treatment of non-operating assets, noting that it considered them in the book value of the business. Since book value was not provided or weighted in the Emory report (or any of the others), it would appear that the court was satisfied that the non-operating assets had little value, since minority shareholders could not gain access to their value until the company was sold. That could be a long time given the desire of the Kress family to maintain family control over the company.

- The Czaplinski report provided for some discounting of the non-operating assets in the marketable minority valuation, and then allowed for further discounting through the marketability discount. Details of her treatment were not provided in the opinion.

Since the court sided primarily with the overall thrust of the Emory report, we see little guidance for future appraisals in the treatment of non-operating assets in this decision.

Item 6: Management Interviews

The court noted that Burns had not visited with management, but had attended a deposition of GBP’s CFO. The court was impressed that Emory had interviewed management in the course of developing his appraisals, and had done so at the time, asking them about the outlook for the future each year. It is not clear from the decision whether Czaplinski interviewed management.

Item 7: Consideration of the 2008 Recession (in the December 31, 2008 Appraisal)

The Burns report was criticized for employing a mechanical methodology that, over the three years in question, did not account for changes in the markets (and values) brought about by the Great Recession of 2008. Specifically, it did not consider the future impact in the year-end 2008 appraisal of the recession’s impact on expectations and value at that date.

Both the Emory and Czaplinski reports were noted as having employed methods that considered this landmark event and its potential impact on GBP’s value.

Item 8: Impact of Family Transfer Restrictions on Value

The court’s opinion in Kress provided more than four pages of discussion on the question of whether the Family Transfer Restriction in GBP’s Bylaws should have been considered in the determination of the discount for lack of marketability. This is a Section 2703(a) issue. Ultimately, the court found that the plaintiffs had not met their burden of proof to show that the restrictions were not a device to diminish the value of transferred assets, failing to pass one of the three prongs of the established test on this issue.

Neither the Burns report nor the Czaplinski report considered family restrictions in their determinations of marketability discounts. The Emory report considered family restrictions in a “small amount” in its overall marketability discount determination.

In spite of the lengthy treatment, the court found that the issue was not a big one. In the final analysis, the court deducted three percentage points from the marketability discounts in the Emory reports as its conclusions for these discounts.

Item 9: Marketable Minority Value per Share

With this background, we can look at the various value indications before and after marketability discounts. First, we look at the actual or implied marketable minority values of the appraisers. For the December 31, 2008 appraisals, the Emory report concluded a marketable minority value of $30.00 per share. Czaplinski concluded that the marketable minority value was similar, at $31.33 per share. The Burns report’s marketable minority value was 50% higher than Emory’s conclusion, at $45.10 per share.

The Court concluded that marketable minority value was $30.00 per share, as found in the Emory Report. That was an affirmation of the work done by John Emory more than a decade ago at the time the gifts were made.

Item 10: Marketability Discounts

The Emory report concluded that the marketability discount should be 28% for the December 31, 2008 appraisal (where previously, it had been 30%). The discount in the Czaplinski report was 20%. The marketability discount in the Burns report (for the IRS) was 11.2%.

There were general comments regarding the type of evidence that was relied upon by the appraisers (restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies that were not named, consideration of the costs of an initial public offering, etc.). Apparently, none of the appraisers used quantitative methods in developing their marketability discounts. The court criticized the cost of going public analysis in the Burns report because of the low likelihood of GBP going public.

Based on the issue regarding family transfer restrictions, the court adjusted the marketability discounts in each of Emory’s three appraisals by 3% – a small amount. Emory concluded a 28% marketability discount for 2008. The court’s conclusion was 25%.

Item 11: Conclusions of Fair Market Value per Share

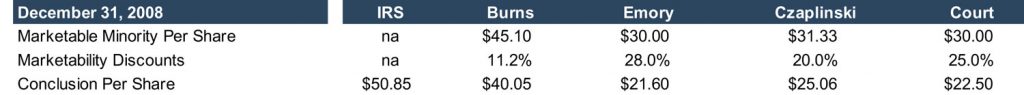

At this point, we can look at the entire picture from the figure above. We replicate a part of the chart to make observation a bit easier.

It is now possible to see the range of values in Kress. The plaintiffs filed their original gift tax returns based on a fair market value of $21.60 per share for the appraisal rendered December 31, 2008 (Emory). The IRS argued, years later (2014), for a value of $50.85 per share – a huge differential. The plaintiffs paid the implied extra taxes and interest and filed in Federal District Court for a refund.

The expert retained by the IRS, Francis Burns, was apparently not comfortable with the original figure advanced by the IRS of $50.85 per share. The Burns report concluded that the 2008 valuation should be $40.05 per share, or more than 21% lower. Plaintiffs went into court knowing that they would receive a substantial refund based on that difference.

Plaintiffs retained Nancy Czaplinski of Duff & Phelps to provide a second opinion in support of the opinions of Emory. Her year-end 2008 conclusion of $25.06 per share, although higher than the Emory conclusion of $21.60 per share, was substantially lower than the Burns conclusion of $40.05 per share.

The court went through the analysis as outlined, noting the treatment of the experts on the items above. In the final analysis, the court adopted the conclusions of John Emory with the sole exception that it lowered the marketability discount from 28% to 25% (and a corresponding 3% in the prior two appraisals).

The court’s concluded fair market value was $22.50 per share, only 4.2% higher than Emory’s conclusion of $21.60 per share.

Based on this review of Kress, it is clear that Emory’s appraisals were considered as credible and timely rendered. Kress marks a virtually complete valuation victory for the taxpayer. It also marks a threshold in the exhausting controversy over tax-affecting tax pass-through entities and applying artificial S corporation premiums when appraising S corporations (or other pass-through entities).

Kress will be an important reference for all gift and estate tax appraisals that are in the current pipeline where the IRS is arguing for no tax affecting of S corporation earnings and for a premium in the valuation of S corporations relative to otherwise identical C corporations.

When all is said and done, a great deal more will be written about Kress than we have shared here, and it will be discussed at conferences of attorneys, accountants and business appraisers. Some will want to focus on the family attribution aspect of the case, but, as the court made clear, this is a small issue in the broad scheme of things.

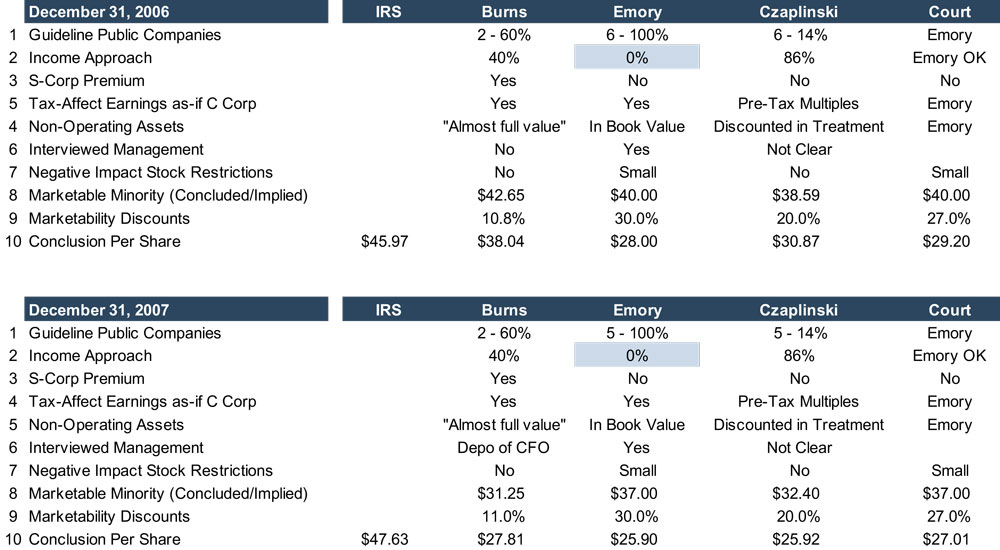

Summary of Other Appraisal Dates

For information, below is a summary of the appraisals as of December 31, 2006 and December 31, 2007.