Are IPOs the New Down Round?

There’s something about nature that abhors a vacuum. Right now that vacuum seems to be the imbalance between the public and private markets, with the latter attracting maybe too much interest since the credit crisis, at the expense of the former. Blame fair value accounting or Sarbanes-Oxley or the plaintiff’s bar, but it has been some time since being public was actually considered a good thing. With interest running high in the “alternative asset space” and cheap debt for LBOs, the costs of being public have not been particularly worthwhile. This situation is not sustainable, and was never meant to be. Family businesses can stay private forever, but institutional investors eventually need the kind of liquidity that can only come from the breadth of ownership afforded by established public markets. Valuations are never really proven until exposed to bids and asks.

So the circumstance in which private capital markets are considered more desirable than public markets is to express an illiquidity preference which is at odds with basic investment logic and the requirements of portfolio management. This cannot last, and the end – which appears to now be unfolding – will ripple throughout the asset management industry.

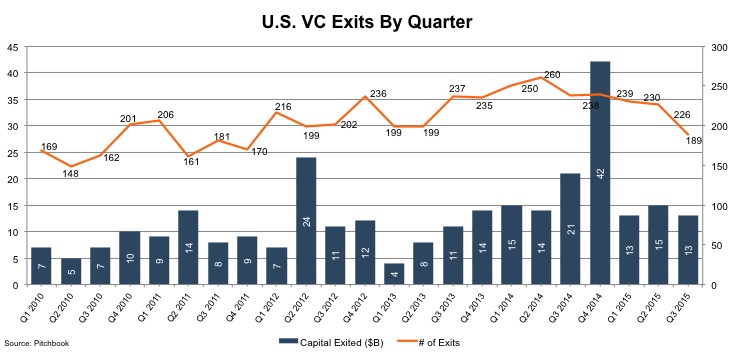

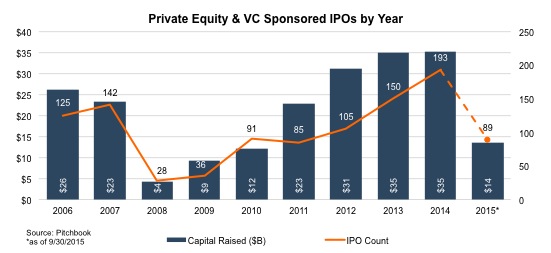

Continuing a trend set into motion in the first half of 2015, third quarter IPO activity fell 34% year over year in 2015, while the median capital raised in private fundraising rounds hit a staggering $92 million. The tech industry in particular has suffered from a glut of capital in late-stage funding rounds, leading to a general hesitation to leave the safe (because it is comfortably theoretical) harbor of the private market. Only 11% of IPOs completed in 2015 so far involved tech companies, with a majority of them generating returns of less than 3% from their IPO prices, and producing a negative 15% from their debut closing prices. Within the tech industry, the sheer amount of capital inflow from the private market has distorted the usual hubbub around the IPO. Private valuations have quietly (and in some cases, publicly) reached levels unsustainable in the public market, and companies now face a reality in which going public may in fact devalue the company – at least from late financing rounds.

It seems only fitting that a company whose entire platform is built on the concept of impermanence should fall prey to the largest tech devaluation in the private market in 2015. Snapchat, a photo, text and video messaging app in which messages “self-destruct” in ten seconds or less, took a hit this past week when it was revealed that Fidelity Investments cut the value of its stake in the company by a whopping 25%. Earlier this year, BlackRock reduced its valuation of the cloud-storage software DropBox by 24%. However, as mutual funds, both Fidelity and BlackRock are obligated to mark their portfolios to market on a regular basis and disclose their valuations. In the third quarter, plummeting gas prices, unstable Asian markets, and whatever new catastrophe was going on with the Eurozone were in full effect. As a result, Twitter saw its stock price fall by 29%, while Facebook also had less than stellar returns. In all likelihood, Snapchat and DropBox were victims of market pressure rather than fundamental performance.

It’s a buyer’s market in the IPO world, as 16% of IPOs downsized their debuts during the third quarter. Investors burned by lower than expected returns in the public market are putting pressure on startups to offer protections or lower their share price. Square, Inc., a mobile payment company founded in the heart of Silicon Valley, recently announced plans to sell 27 million shares in an IPO offering ranging from $11 to $13 per share, a significant discount from the company’s October 2014 funding round that valued shares at $15.46. Granted, late stage Square investors are operating under a “ratchet” agreement (not the adjective kind). Square agreed to provide extra shares to certain investors if the company went public at a share price lower than the funding valuation the investor bought in at. If Square goes public at a share price below $15, the IPO will trigger the ratchet and diminish the outstanding shares. But terms don’t fix price, as the “protection” afforded some Square investors will come from other Square investors. Ultimately, price is a zero sum game.

Although startups do not often publicize whether investor protections are in place, it is an additional factor that has led several startups to postpone a planned IPO. LoanDepot is the latest company to get cold feet before their big day, as the company’s prospective share price plummeted from a high of $18 per share to below $12. Instead of floating the lower valuation, LoanDepot walked, citing “market conditions” as the primary culprit behind the lower valuation. The IPO market has become a waiting game, as more and more startups have punted going public in favor of private capital. Whether the current market squeeze filters its way down to affect private valuations is only a matter of time. It’s hard to imagine that a buildup of companies waiting to go public will somehow improve IPO pricing.

And it is hard to imagine this ending well. ZIRP and arguably over-regulated public markets have created a robust private market, but it is a market of “Level 3” assets without validation. If private markets seize, will they also become more regulated? If rates ever rise significantly, can financing get rolled over to sustain leveraged ownership? Can pension plans and endowments satisfy their funding liabilities without liquidity for alternative assets? At some point, liquidity preference is going to have to restore some reason for public ownership. Ultimately, though, the question is whether that comes from improvement in the public markets or deterioration in the private market.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights