Non-Traditional Venture Investors are Changing The Rules Of The Game

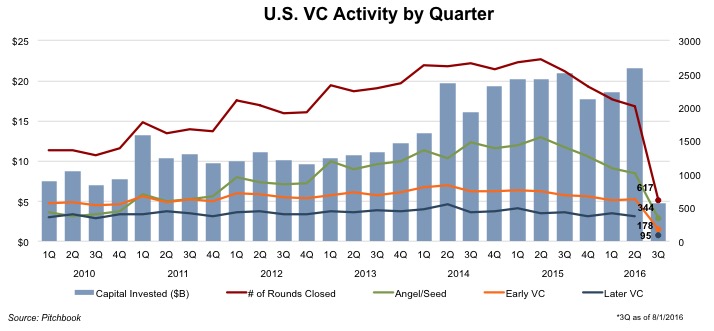

After a steady build up since the end of the credit crisis, it appears that 2016 is going to be marked as the year when the venture capital industry lost momentum, although not for a lack of investors. The birth rate of new unicorns has slowed considerably since their 2015 baby-boom, even as the VC market remains dominated by tremendous inflows of capital in late-stage companies. Money has continued to pour in as riskier VC investments are still expected to outperform listed alternatives due to volatile public markets, higher multiples, low interest rates, and the less-than-stellar performance of the global economy.

The source of new capital has changed, however, as the venture industry saw a marked increase in nontraditional investors – including pension plans, hedge funds and mutual funds. The rise of the nontraditional investor has had a profound effect on VC, from growing regulation and transparency to growing capital and propped-up valuations. It’s an odd situation, where new players are welcomed and then threaten to change the rules of the game.

In 2012, hedge fund managers invested a total of $1.0 billion in capital in the venture industry through 41 closed deals, while mutual funds invested $2.3 billion through 62 deals. By 2015, the amount of capital invested by hedge funds and mutual funds had skyrocketed to $8.3 billion and $14.2 billion, respectively. Due to relatively short-term liquidity needs and investor mandates, nontraditional investors favor late-stage investments, which helps to explain (or at least contribute to) the massive amounts of capital continuing to pour into late-stage rounds.

The only problem, of course, is that the companies have to go public or sell out to a larger player trying to consolidate the industry in order for investors to reap the benefits on the return – and this simply isn’t happening. Instead, the venture industry has seen a barbell form in valuations, with competition driving up prices in both early and late-stage rounds, while leaving mid-rounds behind. This could be the start of a huge problem, because seed stage investment is too small in dollars to be very impactful, and pricey late stage investing appears to be a replacement for the old days when mutual funds could enhance returns with pre-IPO investments. Mid-stage VC is most like the traditional venture industry of a decade or more ago, and it has been left wanting for attention.

Contradicting concerns of a valuation bubble within the venture industry, valuations as a whole have actually held steady through the first eight months of the year. Following the “unbridled enthusiasm” of 2015, however, investors appear to have grown wary, and the industry is at least consolidating gains, if not experiencing a reset. Investors have become more discerning with their investment decisions, only funding rounds for companies with proven track records and strong earnings. Deal counts may have declined at the seed stage, but valuations held strong thanks to more competition and higher standards from early stage investors. The strength of the deals in the seeds stage has pushed into Series A funding, leading to flat valuations and lengthening timelines as early stage companies have struggled to hit the performance standards demanded by investors.

Mid-stage VC is feeling pressure, though. Series B valuations are down as founders are being forced to justify round sizes, while Series C valuations have started to feel the pressure as the intermediate round before late-stage financings.

Series D and later rounds have seen a continued increase in valuations, even as deal sizes have begun to contract due to lower levels of available equity. The average age of companies in the late-stage rounds topped 9 years in the first eight months of 2016. As we discussed in our last venture capital newsletter, late-stage rounds have started to turn towards debt financing in order to maintain growth while avoiding judgement in the public market.

Nontraditional investors are both a blessing and a curse to the venture industry. On the one hand, companies such as Fidelity and T. Rowe Price have continued to accumulate stakes in unicorn companies, often investing after the companies have reached unicorn status and further escalating their valuations. Some have observed that mutual funds are paying up to guarantee share allocations in the event of an IPO, since distribution of smaller IPOs evaporated with consolidation in investment banking. If so, we note that overpaying is not without hazard, as mutual fund mark-to-market accounting seems to frequently, and very publicly, require them to mark down private valuations.

Though mark-to-market accounting has allowed investors a peek into the private nature of the venture industry, it has not necessarily been to the benefit of VC. Companies as big as Snapchat suffered from past markdowns of investments, as Fidelity did in the second half of 2015. In the end, money is money, and the venture industry has reaped the rewards of higher investments from a nontraditional source of funding. The greatest determinant behind the continuation of capital flows from hedge funds and mutual funds lies in the performance (or at the very least, the expectation) of venture exits in the second half of the year. Already, hedge funds and, to a smaller degree, some mutual funds have begun to pull back investment activity amid liquidity concerns, even as hedge funds have struggled to maintain yields. The reset in the venture industry and reemphasis on performance metrics through investor diligence should help close the gap between private valuations and the public market. The question now is how long it will take for the reset to complete, as investors are forced to make hard decisions on liquidity needs in a time of vanishing exit opportunities.

Mercer Capital’s RIA Valuation Insights Blog

The RIA Valuation Insights Blog presents a weekly update on issues important to the Asset Management Industry. Follow us on Twitter @RIA_Mercer.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights