Are Sponsor-Backed Initiatives Distorting RIA M&A?

Barbarians at the Gate 2 – Electric Boogaloo

Prince’s conveyance of choice to the party in 1999: a Plymouth Prowler, in purple, of course (Photo from classiccars.com)

Reading up on the commentary about the record number of RIA transactions last year, I’m struck by how simple the predominant narrative is: everybody wants in, valuations are up, and deal-flow continues to flourish.

Headlines have their own wisdom, but the underlying reality of M&A activity is necessarily nuanced – especially as we approach the twelfth year of this bull market. If transaction activity is higher and vectoring to grow from here, what is the catalyst?

Investment management is a great business. Firms that don’t need to sell, don’t sell. If transaction activity is up, does this mean that more firms need to sell? If pricing and deal terms are better, are the transactions available today really that much more attractive than those available a few years ago? And is the culture of consolidation that has emerged in the RIA community sustainable?

The Go-Go 90s

I’m no Marcel Proust, but these days take me back to the closing months of an earlier bull market that, in many ways, set up where we are today.

1999 was a big year for me in what is now called “adulting.” I turned 30, became a CFA charterholder, and celebrated my fifth anniversary of employment (deployment) with the same firm where I, stubbornly, still work. I became an uncle for the first time, and I was about to become a father as well.

My colleagues and I watched in disbelief as equity markets rose relentlessly in 1999, and I vividly remember saying that one day we would look back and talk about the “go-go 90s.” It was exciting, but it also made me uncomfortable. Warning signs were everywhere. Nosebleed multiples. Pets.com. Nickelback. The handwriting really hit the wall when I saw that the keynote address at the major business appraisal conference that October was to be given by the authors of a then hot but now forgotten book: Dow 36,000.

Cap Rates and Coupons

Dow 36,000 is a clever fairy tale written by a journalist, James Glassman, and an economist, Kevin Hassett. The authors assert that the bull market of the 1990s was fueled, in part, by multiple expansion that would persist as investors came to understand that stocks were no riskier than treasuries. Stock and bond capitalization rates would eventually converge and – voila! – the Dow would quadruple from the levels at which it was then trading. The book was panned by grouchy economists like Paul Krugman and perma-bears like Robert Shiller, the CAPE-crusader who has since predicted at least nine out of the last two financial catastrophes.

Dow 36,000 forecast a sharp rise in the DJIA within three to five years. It’s been two decades, and we still aren’t there – at least in the public equity markets. In the private markets, though, I’m starting to wonder if Glassman and Hassett’s fanciful outlook on valuation has finally been realized.

Adjusted Reality

When the bull market of the 1990s abruptly ended in 2000, one casualty was an energy trading firm with very empathetic accountants. The death of Enron, and the subsequent murder of its auditor, Arthur Andersen, set a regulatory buildup into motion which made it generally disadvantageous to be a public company. 20 years later, the number of U.S. public companies has been nearly halved, and out of the ashes of the public markets rose the phoenix that is private equity.

Private equity can be as much about marketing as it is about markets: convince equity investors to lock up their money for a decade, then convince entrepreneurs to take the money. Cheap debt brings both parties to the table, goading risk-averse investors to chase returns, and teasing sellers with bigger payouts.

Twenty years post-Enron, sponsors have raised the art of “heads I win, tails I win more” to a science. A smorgasbord of cheap debt has enabled financial intermediaries to routinely outbid strategic buyers for three years now. Hockey-stick projections have been supplanted by higher order land-grab economics: the first idea to gain monopoly status wins. Banks compete to lend to sponsors buying asset-light businesses based on EBITDA “addbacks.” LPs look the other way as reality-check IPO exits have been replaced by mark-to-model fund-to-fund transactions. And the SEC is talking about relaxing the requirements to be considered an Accredited Investor. What could possibly go wrong?

Barbarians at the Gate 2 – Electric Boogaloo

The distorted reality of the sponsor community is having an impact on the RIA space as well.

The null hypothesis of the RIA community is that investment management is a relationship business that cannot be scaled. What we are witnessing today is big money trying to disprove that power rests within the advisor/client relationship through ensemble practices, roll-ups, robo-advisors, etc.

The trouble is the current PE model of raising billions to create a monopoly around some lifestyle essential doesn’t work in investment management. Investment management is fragmented for a reason. It is an owner-operator business model. It is a lifestyle business.

Further, what is there to buy? If RIAs only sell when they have to, are consolidators just collections of failed firms? Are they optimized for a bull market? Is it possible to stress-test these models for the next downturn? We’ve recently been passing around a ten-year-old article on consolidation pains in the RIA space that is required reading for anyone who wants to learn from the past, or at least not be blindsided by it.

Is there a sustainable consolidation model? Joe Duran scored big with deliberate, strategic acquisitions of local RIAs into one, nationally branded firm – but the cost of being deliberate is time, something that sponsor-backed enterprises don’t have. The sale of United Capital to Goldman Sachs is viewed by many (not necessarily me) as capitulation, maybe an admission that competing for deals with overcapitalized sponsor-backed initiatives was pointless. Some dismiss the strategic importance of the deal because, for Goldman, the $750 million it paid for United wasn’t much money. That may be true, but Goldman doesn’t do many deals, and didn’t have to do this one.

The brains behind the United Capital acquisition model, Matt Brinker, is now at Merchant Investment Management. Merchant has more of a co-invest mindset, and permanent capital, which says a lot about what the brains of the industry think is a successful consolidation strategy. The co-invest model, in which a financial partner shares with management in equity ownership on a control or, usually, a minority interest basis, seems to have the most traction. We think that approach can work, so long as returns to equity are clearly delineated from returns to labor.

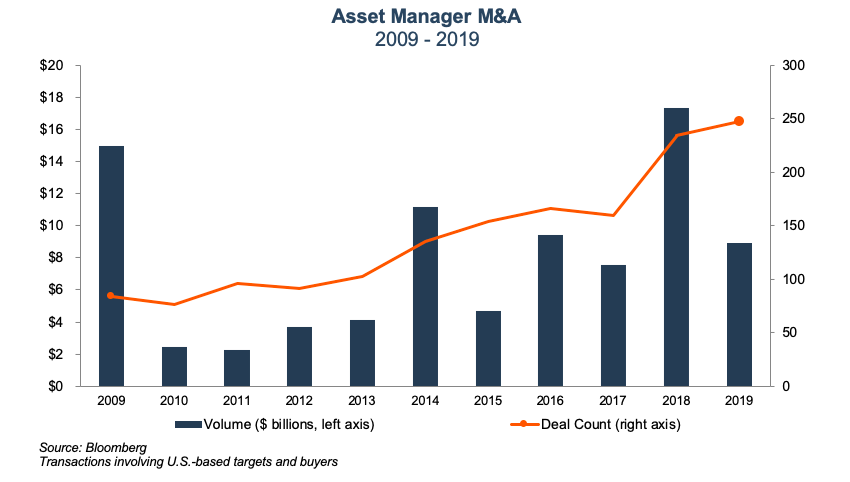

We may have already reached a tipping point. Deal volume was up last year, but deal value was down. The pace of transaction activity established early in 2019 didn’t sustain itself in the fourth quarter – usually a big one. The most visible acquirer in the RIA community, Focus Financial, was called out last summer for becoming over-leveraged. Focus management disputed this, but since then their acquisition announcements have been few.

…like it’s 1999

The song that Prince recorded about 1999 isn’t about the good times; it’s a song about the end-times. As 1999 drew to a close, people weren’t as concerned about the Mayan calendar or Nostradamus as they were about the disastrous consequences of global IT systems locking up because of bad date programming – a fake crisis brilliantly marketed by the IT consulting community to sell their services. The only real crisis was a missed opportunity to have a good time.

My wife and I went out on New Year’s Eve 1999 to a very underattended extravaganza. 80% of the invited guests stayed home, afraid of what I don’t know. Instead of the big blowout that most of us expected in the years leading up to the new millennium, the reality was that partying in 1999 meant withdrawing into a quiet paranoia. If you cringe every time someone talks about selling a company for a big multiple of adjusted EBITDA, you get the idea.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights