This week, news that Apple was canceling what was known as its “Apple Car” project after a decade of work and billions invested puts a spotlight on the troubles facing EV development. As little as one year ago, EVs seemed inevitable, as several automakers declared they would abandon internal combustion engines (ICEs) within the next decade and dedicate their entire fleets to battery propulsion. A decade from now, we’ll know whether media hype over EVs pushed the industry too far ahead of their buyers, whether media hype turned willing EV buyers against battery-powered cars, or some combination of the two.

What can be said of Apple’s decision, much like many other start-up automakers over the past century, from Tesla to Fiskar to Hudson, is that manufacturing cars is both incredibly difficult and incredibly expensive. If you’re Apple, you have no shortage of design engineering talent. Doing hard things very well is table stakes at Apple. But talent can’t guarantee payoff if the market for your product doesn’t exist. No doubt Apple re-examined market appetite for EVs and decided their venture wasn’t worth further capital investment.

Returns to Labor Versus Returns to Capital

RIAs don’t make major capital investment decisions like industrial companies, but their resource allocation thinking can be modeled similarly. Investment management is not capital intensive, but it is labor intensive. The operating assets of an RIA don’t appear on the company’s balance sheet — they go home each night. Sometimes, they go elsewhere.

One way to look at the specifics of a given RIA’s business model is to think about how they value returns to capital versus returns to labor. Specifically, returns to capital for an RIA are thought of as distributable cash flow, or margin. That margin is the net result of revenue and an expense structure. In any financial measurement period, revenue is known, and non-compensation operating expenses are mostly fixed, such that everything else is either a return to labor (compensation) or a return to capital (distributions). Professional firms, including RIAs, often view compensation and distributions as competing with each other. We often look at the proportion of returns to labor and returns to capital as being descriptive of the priorities of the firm, the efficiency of its model, and the outlook for the business.

Team Building and Capital Budgeting

Sometimes, the tradeoff between returns to labor and returns to capital shouldn’t be looked at in one-year increments but over many years, like an industrial company would model their capital budget. Significant investments in adding client service teams, promoting a layer of staff on the org chart to a higher level, or adding an incentive compensation program can be modeled as a tradeoff with near-term investments that lead to lasting benefits.

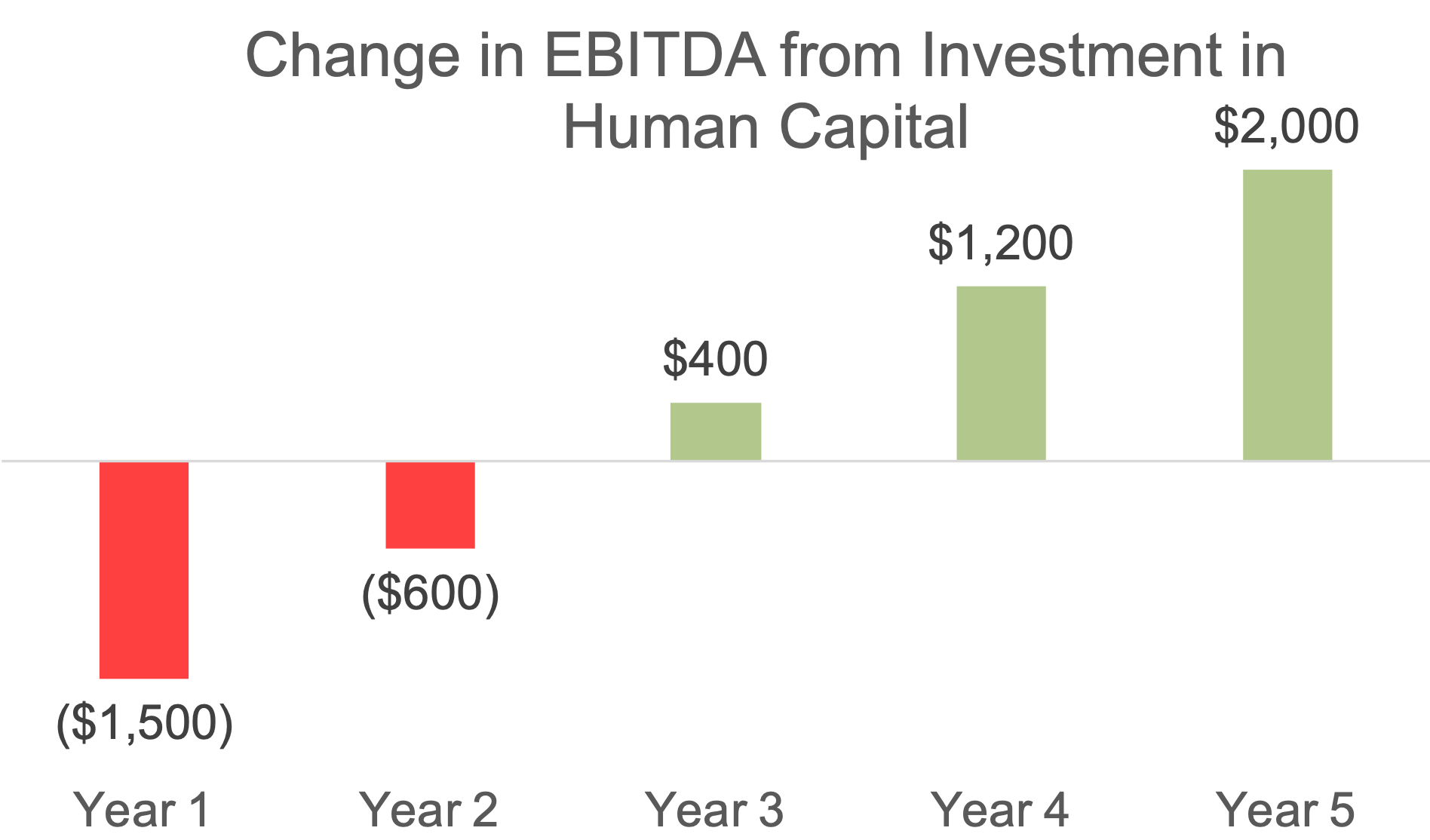

Take, for example, the proposition of adding a client service team to cover a group of wealth management clients from existing teams such that they would have the capacity to grow. In the short run, adding the new team might decrease profitability. In the longer run, if the investment makes sense, the increase in profits from the investment will provide a rate of return that is higher than the firm’s cost of capital.

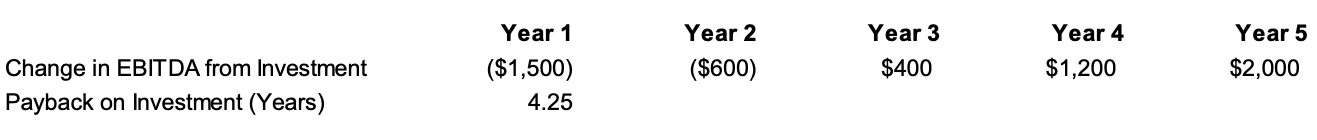

With reasonable expense and income projections in hand, we can look at this investment in human capital much as an asset-intensive enterprise, like manufacturing, would look at a regular capital investment: payback period and rate of return. The team expansion above has a specific cost that has a negative impact on returns, but when those turn positive, we can look at the “cost” of the investment in terms of payback. In the case we show here, the payback period is only 4.25 years.

With reasonable expense and income projections in hand, we can look at this investment in human capital much as an asset-intensive enterprise, like manufacturing, would look at a regular capital investment: payback period and rate of return. The team expansion above has a specific cost that has a negative impact on returns, but when those turn positive, we can look at the “cost” of the investment in terms of payback. In the case we show here, the payback period is only 4.25 years.

Click here to expand the image above

Using different assumptions, we can stress-test this and see how long it might take to get a reasonable payback of the initial investment. Shorter is obviously better, but even longer-term paybacks can provide tremendous rates of return when coupled with the impact on firm value.

Think about the rate of return on our example. It would include not just the change in EBITDA over the ramp-up in profitability from the investment, but also the impact on valuation. At an EBITDA multiple of 8.0x, that $2 million in additional value in year 5 increases the value of our RIA by $16 million. A simple IRR calculation suggests a return of over 80%. Disclaimer: your mileage may vary.

Click here to expand the image above

When we take the model of allocating returns to labor and returns to capital out of a one-year margin versus compensation construct, we can open the discussion to something much more powerful: being long-term greedy. A little give on margin in the short run can grow longer-term profitability such that the re-investment in staff provides a tremendous rate of return.

And this longer-term thinking about investment in human capital offers strategic decision-making tools for RIAs more akin to capital budgeting for a more asset-intensive business. With that toolkit in hand, it’s easier to think of how to put your firm’s resources to work where they are most likely to make the firm more money over the next five years than it made over the last five years.

Back to Apple. In ten years of development, two things have happened to their automaking ambitions: more competition and less market interest. A small change in outcomes can have a huge impact on capital budgeting decisions. Fortunately, the investment management space is not that dynamic, and injecting a bit of heavy industrial thinking into investing in human capital can provide big returns. The tradeoff between profitability and compensation does not have to be a zero-sum game, and the benefits of being long-term greedy cannot be ignored.