Summer Reading for the RIA Community

Focus Financial’s IPO Filings

Aston Martin DB11, custom spec’d as a tribute to the North Coast 500 by the AM dealer in Edinburgh (photographed at Gleneagles Hotel by Rod McAllister).

Money, being what it is, never sleeps. It also never goes on vacation. I was, however, about to spend ten days away from the office with my older daughter in Scotland and England when Focus Financial (finally) filed for a public offering. One of the most anticipated events in the wealth management industry, the pendency of the Focus IPO didn’t cancel my trip, but I knew that my vacation was going to be at least punctuated by reading the S-1 along with my peers’ commentaries. I’ve now read the 275-page document a few times, and while it’s not your typical beach novel, the Focus prospectus is required summer reading for anyone in the RIA community.

The First Question to Ask of Any IPO is “Why?”

Initial public offerings are sacramental in the church of capitalism. At one time, IPOs represented a coming-of-age when growing asset-needy businesses could finally have the financing they required to expand into leading, mature organizations. Today, public offerings may just represent the day when private equity backers decide they would rather someone else own a business instead of them. IPOs can, in many cases, be read as a sell-signal.

In spite of this, public offerings still generate a surprising amount of enthusiasm. My daughter and I started our trip at the Aston Martin dealership in Edinburgh, and the characteristically friendly Scots there chatted excitedly about Aston Martin’s upcoming IPO whilst making sure my daughter learned the ins and outs of at least a million pounds worth of stainless-steel, aluminum, and carbon fiber. Aston Martin’s IPO not only represents permanent equity backing for a uniquely capital-intensive business, it is also the triumph of a marque bought out of obscurity by a wealthy English industrialist, Sir David Brown. Brown not only manufactured and sold tractors by the thousands, he also understood the halo effect of auto racing to underscore a nation’s industrial competitiveness, and he was tired of seeing English cars lose to the Italians. Sir David was also savvy enough to take a page out of Enzo Ferrari’s business model and financed his passion for auto racing by selling expensive road cars. It was a prescient decision for Brown, as his eponymous series of “DB” cars were adopted by a mythological British figure, James Bond, and the combination sustained the brand’s identity for fifty years. It is highly unlikely that the DB11 would exist today if Sean Connery hadn’t been assigned a DB5 as his company car in the 1960s.

Today, Aston Martin is once again following in the hoof-steps of the prancing horse, as Ferrari’s 2016 public listing was a huge success (NYSE: RACE). Ferrari is much more than an automaker, of course; it is a brand. Despite devotees like yours truly, Aston Martin’s intellectual property is no match for Ferrari, which boasts an adjectival name, a primary color, and a mascot that are instantly recognizable and merchantable. For Aston Martin’s listing to be successful, it will have to make it as an automaker instead of a fashion label – no doubt a much tougher slough.

What Exactly is Focus Financial?

All of this brings me back to Focus Financial, whose business model is a little difficult to, well, focus. The IPO is being hailed as a validation of the RIA industry, but the RIA industry doesn’t really need validation (it is proven and profitable) and Focus isn’t really an RIA.

The Focus brand, for example, doesn’t really extend to the investors with their partner firms. If you review many of their partner firm websites, for example, you don’t see much mention of Focus, and any mention certainly isn’t prominent. Focus’s brand is directed at the acquired firm, a back-of-the-house system. The storefront is still the individual tradename and people of the partner RIA. In much the same way, the Focus financial statements aren’t really the consolidated statements of their affiliate firms, but rather a specifically defined interest in the cash flows of the affiliate firms. In mathematical terms, you might say that the calculus of the Focus financial statement is the first derivative of an RIA income statement rather than the RIA income statement itself.

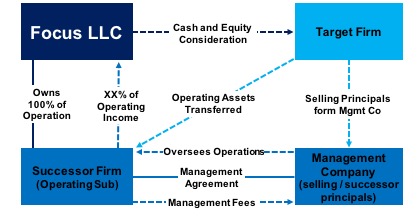

Focus acquisition model (adapted from pages 120-121 of the prospectus)

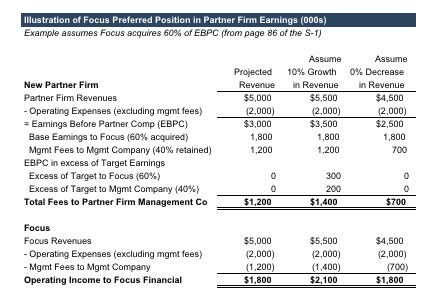

Focus Financial is an aggregation of RIA cash flow streams, contingent rights, and responsibilities. The Focus model is to acquire between 40% and 60% of an existing RIA’s earnings before partner compensation, or EBPC, which post-acquisition is referred to as “target” earnings (Focus also has a program for wirehouse broker groups who want to go independent). The remaining EBPC is retained by a management company formed by the affiliate firm as a wage pool for selling partners. Focus takes a preferred position in the affiliate firms’ EBPC; the selling partners are responsible for delivering at least the dollar portion of EBPC sold to Focus (termed the “base” earnings). Any excess above target earnings is split pro rata. This asymmetric payoff dampens the downside volatility for Focus, but obviously also raises it for selling partners. Focus has a handy chart in their S-1 that illustrates the potential repercussions of this on partner firms.

As shown in the example above, assume Focus acquires 60% of a selling firm’s earnings before partner compensation and EBPC is $3 million. If revenue grows by 10%, EBPC grows to $3.5 million. In the upside scenario, selling partners and Focus share in this 40%/60%, and selling partners see their management fees increase from $1.2 million (40% of EBPC established at time of sale) to $1.4 million (the $200 thousand increase representing 40% of the overall $500 thousand increase in EBPC). One can see how enough growth in AUM enables selling partners to recover their pre-acquisition compensation level, in addition to receiving proceeds from selling rights to part of their EBPC to Focus. The downside scenario is fairly dramatic, however. In the example, a 10% drop in revenue causes the selling partner compensation pool to drop by almost half, from $1.2 million to $700 thousand, which is less than a quarter of pre-transaction partner compensation.

Because we haven’t experienced a sustained bear market since Focus completed most of their acquisitions, the downside implications of this arrangement on selling partner groups (and, in turn, on Focus) aren’t yet fully known. The disproportionate risk borne by the partners of affiliate firms is, presumably, known to them – although knowledge and experience sometimes yield different outcomes. We wonder how selling partner groups would behave in a market environment in which their compensation was severely restricted, remembering that retained EBPC is effectively wages for the continuing efforts of affiliate firm leadership.

How Does Focus Pay for This?

As anyone who reads this blog is fully aware, RIA transactions are typically a mixture of upfront payments and contingent consideration. Focus is no different, and while the prospectus doesn’t describe a sample transaction, it is clear that Focus uses both cash and equity to provide fixed payments and earn-outs. The equity consideration is valued by Focus, apparently with the assistance of third-party appraisers (not us!). More than one commentator has suggested that a downside to Focus Financial going public is that they can no longer “assign” a value to their stock, as it will now be determined by market. I’m sure that my peers who provide valuation services to Focus don’t appreciate the slight.

The valuation of Focus is, at this point, somewhat complicated, and we are very interested to see how the market treats them. In 2017, Focus reported a loss of nearly $50 million on total revenues of $663 million. Last year was a good year for most RIAs, and to explain their loss, Focus management suggests a lengthy list of adjustments to get to a pro-forma EBITDA margin of about 22%. Market pundits so far are suggesting an enterprise valuation of $2.0 to $2.5 billion for Focus, which works out to about 8x to 10x pro-forma EBITDA.

The question becomes whether or not you agree with all of management’s adjustments to travel from reported to pro forma EBITDA. Some off these add-backs are not controversial (eliminating non-recurring items such as delayed offering cost expenses), but over a third of management’s adjusted EBITDA for 2017 comes from eliminating non-cash equity compensation expense and adding back the change in fair value of contingent consideration.

The analyst community remains divided on how to treat equity compensation, but we quote Warren Buffett’s old saying –

“If stock options aren’t compensation, then what are they? If compensation isn’t an expense, then what is it? If expenses don’t belong on the income statement, then where do they belong?”

For a shareholder in an acquisition platform like Focus Financial, equity compensation and contingent consideration are dilutive to earnings per share, and one would expect them to be recurring in nature. Further, a 22% EBITDA margin is low for a large RIA – even on a reported basis. Then again, Focus isn’t really an RIA.

So we don’t have a good sense of what Focus’s profit margins will be once it matures to a steady-state enterprise. The financial history shown in the S-1 doesn’t really demonstrate the kind of operating leverage we might expect, but, to be fair, I think it’s still too early to tell.

What Does Focus Do After an Acquisition?

While the 55 Focus partner firms employ over 2,000 people, the holding company itself has about 70 staff members, most of whom are charged with growing cash flows through acquisition or by improving affiliate firm profitability. To enhance organic growth, Focus has staff assigned to affiliate RIAs to provide them with ideas to improve operations and marketing, much as broker-dealers do for their network affiliate RIAs. Eventually, Focus will have to transition from an acquisition platform to an operating platform, and these services will become more critical to fueling the growth engine.

It’s worth pointing out that there is a cost to the staff and their activities at the holding company that is borne under the Focus model but not by an otherwise independent RIA. Further, the Focus prospectus doesn’t suggest that this cost is mitigated by explicit post-acquisition synergies such as personnel redundancies, although this probably happens from time to time. In addition, the prospectus is explicit that holding company staff is there to assist partner firms with growth and operations, rather than to impose rubrics and expectations. The idea is to maintain the entrepreneurial spirit of the partner firms and to avoid “turning entrepreneurs into employees.” Can thousands of people be directed with only carrots and no sticks? Probably not, and I’ve no doubt that Focus management realizes that.

One test of the Focus model is whether or not the staff at the holding company can pay for themselves. Can they improve partner firm cash flows to more than offset the cost of the aggregation? If so, this will be a big success.

Does the Focus Model Work?

Focus has been in operation for a dozen years now, but it’s still very much a development stage company. Focus has proven itself as an acquisition platform. RIA transactions are difficult, and Focus has managed to attract and retain 55 direct partner firms. Several of these firms have themselves engaged in acquisitions after they became part of the Focus network, bringing the total number of firms under one umbrella to 140. Indeed, one major asset Focus can boast is its knowledge of the RIA firm landscape and how to successfully acquire and integrate wealth management firms.

That said, acquisitions either consume distributable cash flow (the prospectus is clear that the company does not plan to pay dividends, which is very different from typical RIAs) or result in equity issuance (which can be dilutive of existing shareholder returns). Focus can build shareholder value by arbitraging returns if it can acquire firms at a lower multiple than it trades for, but this requires the market giving it a premium multiple on a sustained basis. Since acquisition multiples in the RIA community don’t usually happen at substantial discounts to publicly traded asset managers, it may prove difficult to enhance shareholder returns through acquisition – at least on a sustained basis.

No doubt Focus has plenty of room to run as an acquisition platform, but longer term shareholder returns will require Focus to develop an operating platform that widens partner firm margins and speeds revenue growth to a greater degree than those same firms would do on their own. One test is easy to measure, and the other is not. Together, they form a major part of the holding company’s “alpha.”

Analysts can look at Focus’s profitability and determine whether the model enhances RIA cash flow or not; as I mentioned earlier, current margins suggest they still have room for improvement. Determining whether or not an affiliate firm is growing faster in association with Focus is more difficult – there are many variables that would have to be isolated to do that. Since management teams share in profit increases, they theoretically have incentive to help the organization grow. Post-acquisition, of course, Focus takes a pro rata piece of that increase in profitability, and while the selling generation of partners gets compensated for this in the form of earn-out payments, successive generations will not. It will be interesting to see how second-generation partner firm leadership behaves.

The Focus S-1 reports organic revenue growth – essentially same store sales growth – of 13.4% for 2017 versus 2016. Organic growth for the prior two years was reported in the mid-single digits. Whether or not those organic growth rates best industry averages depends on whom you ask. We think this will be a closely studied metric for Focus as it matures.

Further, because Focus is an amalgamation of RIAs which still report independently, it is possible to review ADVs and track their partner firm AUM over time. We’ve done this, and the study predictably shows a wide variety of growth patterns across these businesses which are still run as independent entities. Some appear to have grown more rapidly after being acquired by Focus, and others not so much. It would take a good bit of work to track these growth patterns relative to financial market behavior, industry trends, and to segment out partner firms that are growing at least in part because of their own acquisitions. For now, Focus’s report on organic growth may be the favored big-picture performance measure.

What Questions Remain?

The most significant remaining queries for Focus Financial revolve around the theme of sustainability. In the near term, can Focus continue to attract enough sellers to monetize their know-how and identity as an acquirer? In the longer term, can Focus transition into an operating brand and grow organically in such a way that it proves the value they add as an organizing force in the RIA space? Will they show growth rates and margins that prove the value-add of the holding company?

Focus is organized as more of a quilt (independent businesses) than a blanket (think wirehouse). Given that, can Focus direct their partner firm employees’ and principals’ zeal while avoiding the behavioral risks that come with independence? Will Focus ultimately have to become more regimented in the investment products it offers, the marketing approaches its advisors employ, the training and compliance procedures they require, etc.? There is a natural tension in all investment management firms between development and risk management, and as firms grow, the latter usually overtakes the former.

Will succeeding generation leadership at partner firms be sufficiently incented to continue the growth that first made them attractive as acquisition candidates to Focus? The selling partners of affiliate firms have a relationship with Focus that younger members do not share.

Why Does All This Matter?

Most of the questions I’m throwing out in this blog post apply to the broader RIA universe, and not just to Focus Financial. The Focus IPO is significant because it represents the single-most direct response to major industry issues, while at the same time leveraging industry trends. With managed assets increasingly leaving bank-controlled brokers, the retirement era of the baby-boomers leading more and more assets to independent firms, and a transition planning crisis among RIA ownership groups, someone had to develop a model to organize, if not consolidate, this highly fragmented industry. Fourteen years ago, Focus’s founder Rudy Adolf sat at his kitchen table and decided to do just that.

The Focus prospectus makes it clear that engineering a profitable solution to the RIA industries primary conundrums is not, however, as easy as defining the situation itself. As a conglomeration of independent businesses, the Focus financial statements are themselves gerrymandered in a way that takes some getting used to, and we don’t think their results will track the RIA industry as closely as some have suggested.

None of this detracts from what Focus has accomplished. They have developed a business model to address very difficult acquisition and integration issues and have steadily grown their brand as an acquirer in the parentage of several prominent PE sponsors. In going to market, Focus management is committing to prove viability in public filings, conference calls, and daily trading. It is a major undertaking for any company, but even more so for the one who goes first. If Focus Financial is, like Ferrari, successful as a public company, no doubt Hightower and United will, like Aston Martin, consider following their lead.

We look forward to seeing more.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights