RIA Dealmaking in a Post-ZIRP Market

Terms Bridge Seller Expectations and Market Realities

1991 Porsche 911 Carrera 4, heavily modified by Singer Vehicle Design (sold for $1.2 million on bringatrailer.com)

How do you sell a 30-year-old car for ten to twenty times the prevailing price? If it’s a 964-era Porsche 911, you trailer it to the folks at Singer Vehicle Design. After heavily optimizing the motor, lowering the body, improving the suspension, strengthening the frame, dressing up the interior, and slathering the body with custom paint, your humble used car will be transmogrified into a pavement-devouring, one-of-a-kind work of art. The one above sold for $1.2 million back in the fall, many times the typical $50 thousand to $75 thousand pricing for 911s of that vintage. Sales in the upper six to seven figures are not unusual for Singer creations.

How Do You Sell an RIA for Peak Cycle Pricing in a Post-Peak Market? Terms!

A well-worn saying in M&A is, “You tell me the price, and I’ll tell you the terms.” Nothing could be more apt for the current state of transaction activity in the investment management space. Two years ago, conditions were perfect for maximum valuations. Today, not so much. But deal volumes are only off slightly, and deal “valuations” are also only off slightly. What gives? Creative deal terms allow transacting parties to maintain a veneer of peak pricing while protecting buyers if conditions worsen.

With a bull market in equities plumping revenue, low inflation fluffing margins, and all-but-free debt fueling large and prolific acquirers, pricing for RIA transactions in the 2021 timeframe got well outside of historical norms. Since then, markets are wobbling, compensation expense threatens margins, and the cost of capital—after 500 basis points in Fed rate increases—is considerably higher. While we are seeing some impact on M&A pricing and activity, it’s not yet proportionate to the changes in market reality.

Indeed, while higher interest rates and economic concerns have wounded the housing market, maimed commercial real estate, and bludgeoned regional banks, the RIA space is comparatively unscathed. There are generally fewer acquirers at the deal table, the names have changed somewhat, and several of the big players of 2021 are sidelined. But many consolidators are still out there. And new buyers with fresh powder, seeking what one told me was a “third-mover advantage,” have emerged. The beat goes on.

This circumstance compels us to explain how to bridge the apparent disparity between price and valuation. Note: industry participants often use the term “valuation” interchangeably with “price” in describing the economics of a deal. We’ll stick with the more classical definition: price is the stated consideration paid in a transaction, and valuation is a cash-equivalent concept that summarizes the financial merits of a subject enterprise to knowledgeable and dispassionate investors.

“Risk-Sharing” — in Theory

Risk-sharing is a term we hear more often to describe buyer-seller relationships in RIA deals. RIA buyers were always loath to trade cash for keys and hope for the best. These days, as I’ve said before, sellers are making as much of an investment in the buyer as the buyer is in the seller.

Risk-sharing through deal terms is a mechanistic exercise that can involve any number of techniques. The two most common are stock consideration and earnouts. These two aspects of deal consideration are not new, but in this environment, they’ve taken on a much greater degree of prominence and peril.

Sellers would be well advised to look through the stated pricing they’re being offered and think about the potential outcomes of their transaction and what those outcomes mean to the cash-equivalent valuation being placed on their company.

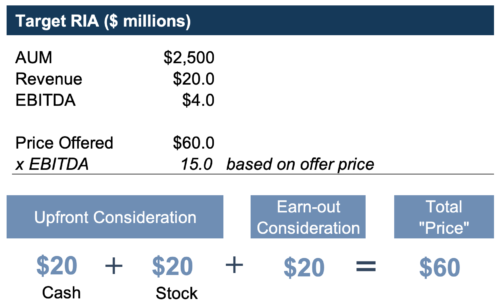

Risk Sharing in Action: Best Case, Deal Prices at 15x

Imagine a target RIA with $2.5 billion in AUM, $20 million in revenue, and $4 million in adjusted EBITDA. Private consolidator offers $60 million for the firm’s equity, with two-thirds of it paid at closing and one-third as an earnout. $60 million is 15x EBITDA, and the seller is elated.

That transaction multiple of 15x is predicated on a number of assumptions:

- The stock offered is actually worth the assigned value of $20.0 million and can be monetized for that amount. This is a major assumption, as a liquidity event may be many years in the future, and to assume the stock consideration is worth what it is supposed to be to the seller today, we also have to assume that it will return a reasonable cost of capital over a holding period.

- This transaction price also assumes the earnout consideration will be paid. This is a function of 1) how ambitious the terms of the earnout hurdles are, 2) market conditions over the terms of the earnout, and 3) the actual value of the earnout consideration (in the case of stock consideration as opposed to cash). One way to look at this is a set of conditional probabilities (e.g., an 80% chance of achieving the earnout hurdle and an 80% chance of favorable markets, and an 80% chance of monetizing any consideration paid for achieving the earnout is a conditional probability of 80% x 80% x 80%, or 51%). A valuation of the earnout would also consider a cost of capital until the earnout is paid.

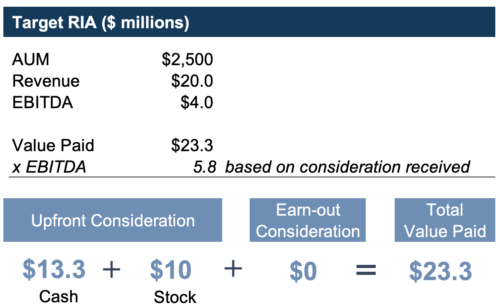

Risk Sharing in Action: Worst Case, Deal Prices at < 6x

The most secure aspect of the offer is the cash consideration up front, but much of that will be necessary to pay taxes on gains on the transaction. If the seller has a minimal basis in the stock in their firm (not unusual) and assuming a blended capital gains tax rate of 25%, half of the cash consideration would be expended to cover taxes on the $40 million in the initial deal consideration. That $10 million in net cash proceeds is worth about $13.3 million on a pre-tax equivalent basis (if the cash is looked at in isolation).

If the value assigned to the stock consideration is high, then the likelihood of monetizing it at the assigned value is low. Plenty of industry commentaries have noted that private RIA space consolidators valued themselves at twice or more than the multiples observed in publicly traded consolidators. And justifying the degree of multiple arbitrage between consolidators and sellers in the RIA space assumes exit opportunities that may not materialize. Eventually, something’s gotta give.

So, if half the cash is used to settle taxes at closing, and if the stock consideration is worth half of the assigned value, and the earnout isn’t achieved, the $60 million transaction at 15x EBITDA turns into a $23 million transaction at less than 6x EBITDA.

A worst-case scenario like this does not represent the “value” of the deal or of the target RIA, but it does illustrate the possibilities of “risk-sharing” with a buyer in a transaction, and it goes a long way to explaining how current market conditions haven’t overly impacted transaction pricing.

So, how does a seller evaluate how much risk-sharing they should be willing to accept?

Stock Consideration Is an Investment in the Buyer

Gone are the days of all-cash offers. Buyers now require sellers to accept rollover equity for their firms. As illustrated above, this protects the buyer in a number of ways:

- Sellers are literally invested in the success of their buyer

- If the buyer’s stock is valued at a higher multiple than they are paying for the seller, the buyer gets the benefit of multiple arbitrage

- If buyer performance (and valuation) sags, that pain is spread to more participants

- Buyers don’t have to part with as much precious cash, of which they have a finite amount to do deals. Issuing equity is a comparatively painless, infinite source of deal consideration

In its simplest form, stock consideration comprises shares in a public company and is subject to little in the way of restrictions on liquidity. Most RIA consolidators are not, however, public, so shares issued to a seller in an acquisition have risks related to value and liquidity.

I watched a panel presentation last year in which three acquirers, in the same presentation, referred both to making acquisitions of target firms at 10x (presumably EBITDA) and to their own stock being valued at 18x, 22x, and 26x. Hmm. Suffice it to say, share for share exchanges are exercises in which relative value matters. If an acquirer values you at 10x and pays you stock they say is worth 20x, you are, in effect, giving up a claim to one dollar of earnings for every fifty cents you receive in return. If their share price holds up or improves, stock consideration can go very well for a seller. The reverse is just as true.

Just remember that accepting stock consideration is tantamount to making a direct investment in the buyer. Valuation matters. Time horizon matters. Concentration risk matters. Liquidity matters.

Betting on the (Your) Future

The intellectual conundrum of earnouts is they conflict with one of the primary goals of sellers: offloading the risk of the performance of their business onto someone else. But that’s an academic argument with no practical value here; without earnouts, transactions in businesses like RIAs would be nearly impossible.

Earnouts have long been a way to bridge the differences between seller expectations and buyer concerns. Earnouts can be structured in any of a myriad of ways, but most of them can be categorized as:

- Securing the business. Earnouts paid based on the stability of revenues, maintenance of a certain percentage of accounts or AUM, or delivering a run rate of profitability—all for a reasonably short period like one or two years—ensure that the business delivered is the business advertised. It’s not up to the seller to grow the business so much as it is their responsibility to help ease the transition so the buyer can successfully take over profitable relationships. If these types of earnouts are structured based on maintaining a certain percentage of client relationships, they are less subject to market fluctuations and involve less risk for the seller.

- Continuing the trajectory. If a firm has shown fairly consistent growth over recent history, it might be reasonable to motivate the seller to keep developing their practices after the sale and thus pay an earnout with a hurdle of reasonable, continued growth. These earnouts tend to be structured a bit longer—two or three years—to integrate the development function into the acquirer.

- Stretch goals. We’ve seen big earnouts offered based on big growth hurdles. There’s nothing wrong with throwing something up to motivate the continuing management team of the selling firm—but it’s really a way of saying that the buyer will pay a lot more if they get a lot more. That’s not magic, and it also really isn’t deal consideration because they aren’t offering to pay that much for the firm as it existed at close.

Serial acquirers don’t want the reputation of not paying earnouts, but it happens. In recent years, we’ve seen examples of public acquirers who had to disclose writing down their contingent consideration liabilities because they didn’t expect targets to hit their hurdle rates. If we go through a cycle of market malaise, more sellers are going to be disappointed.

RIA Dealmaking in a Post-ZIRP Market

We’ll be dealing with the aftermath of zero-interest rate policies (ZIRP) for years to come. One theme tying together many of the reverberations of normalizing debt costs is how to unwind expectations set by markets when the cost of capital was nil. You can’t just pretend nothing has changed.

Seller expectations are sticky, but buyers who overpay will be left holding the proverbial bag. So deal terms will continue to evolve to find a way to reward sellers when things go well and protect buyers when they don’t. Our only warning to sellers—and buyers—is to look carefully at the underlying value of a transaction and not just the headline price.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights