Does the Money Management Industry Need Consolidation?

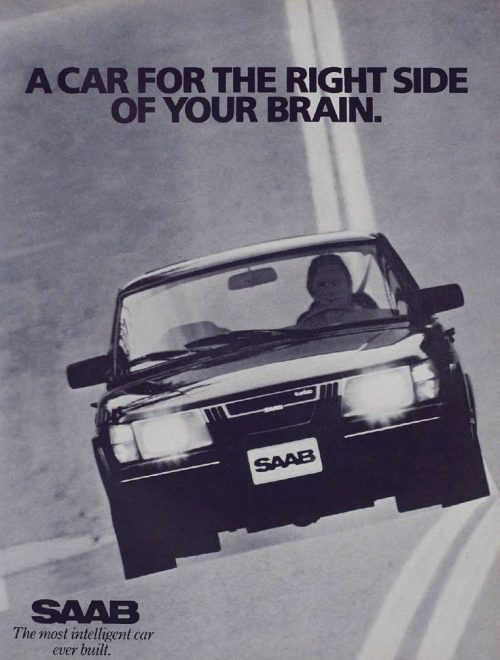

Saab Story: A 1980 model of the iconic 900 Turbo, well before GM got their paws on the marque (photo from automobilemagazine.com)

As World War II drew to a close, a military aircraft manufacturer in Sweden saw the post-war consumer economy as an opportunity to expand into cars, and the Saab automobile was born. For about 45 years thereafter, Saab established itself as a scrappy automaker known for innovation. Saab was the first automaker to introduce seatbelts as standard equipment, ignition systems that wouldn’t crush a driver’s knees in a collision, headlamp wipers and washers, heated seats, direct ignition, asbestos-free brake pads, and CFC-free air-conditioning. Saabs were distinctive, substantial hatchbacks with strong but efficient motors and enjoyed a devoted following. Unfortunately, Saab’s fan base was too small, and as the company struggled to build the scale necessary for global distribution, financial troubles drove them into the gaping maw of General Motors.

In the late 1980s both GM and Ford were attempting to consolidate global automotive capacity and bring as many brands under their corporate hierarchy as possible. With consolidation came homogenization, as global behemoths looked for ways to cut manufacturing costs. Under Ford’s ownership, Jaguar and Aston Martin starting sharing parts with each other and their Dearborn parent. Ford, arguably, saved both marques and orphaned them before they were ruined. Jaguar is thriving today, and Aston Martin is planning its first public offering. Saab wasn’t so fortunate, with GM blending Saab’s mystique with Subaru (sushi with meatballs?) and Saturn (a space oddity if there ever was one). Saab struggled for about twenty years in GM’s dysfunctional family, but eventually the brand was wrecked and Saab was no more.

Divergent Industry Tensions

Like the automotive industry in late 1940s and 50s, the investment management industry is characterized by scores of independent firms who have found success in idiosyncrasy, providing clients a limitless variety of paths and approaches to common investment dilemmas. Some would suggest that this is the source of the industry’s strength, but not everyone agrees, as evidenced by the Focus Financial IPO two weeks ago.

A key element of the Focus market opportunity is “fixing” the fragmented nature of the RIA industry, providing an ownership structure, exit opportunity, and transition mechanism for the thousands of independent advisory practices with a stream of profitability threatened by aging founders. This opportunity exists in an industry that is far from declining – in fact it is growing in clients, assets, and advisors. Focus can provide ownership transition capital to bring some order to this creative process and share in the profits along the way.

The RIA industry is growing, but it is doing so because it is largely in a stage of de-consolidation, rather than consolidation. Most of our clients set up their own shops – whether in wealth management or asset management – because they were exiting larger firms they felt restricted their thinking, their business development, and their incomes. Investment managers are characteristically independently minded and entrepreneurially motivated. In many ways, the increase in investment advisory practices is an effort to recapture the careers available to what were once called stockbrokers forty years ago. One client of ours who escaped his wire house environment earlier this year decried how his former firm had been taken over by lawyers and accountants who were conspiring to restrict opportunities for both him and his clients.

So many wire houses are now losing advisors to the RIA industry, broker protocol is splintering, and the only BDs reporting growth in advisors are doing so at great recruiting costs, which may or may not be recoverable. The alternative would be to acquire practices outright, but great entrepreneurs make miserable employees. Focus aims to thread this needle by acquiring a preferred interest in the profitability of partner firms (defined as Earnings Before Partner Compensation, or EBPC) that assures Focus a basic rate of return on investment but leaves the leadership of partner firms the opportunity for upside. Further, while the Focus holding company will provide programs in products, marketing, and compliance to partner firms, opting-in to those programs is treated like coaching, rather than being compulsory.

Will the Focus “preferred stake in EBPC” work? Will selling partners be motivated enough to continue to grow their practices profitably? Will subsequent generations of partner firm leadership have enough upside to stick around or will they seek out other opportunities? Is coaching through encouragement enough to manage the activity of boutique investment advisory practices? Can subsidiary firm margins been grown enough to offset the corporate overhead of the parent?

The Prevailing Rhythm

We are obviously skeptical, but we’re not cynical. We’ve been around long enough (and have been wrong enough), so we are intently watching and listening to the drumbeat of the consolidators. Focus has put more thinking and garnered more capital to try to build critical mass in the wealth management industry than anybody else. They are not the only group trying to do this, but they’ve gone farther than anybody else. We don’t buy the idea that Focus is the public company barometer of the RIA industry, but it is the barometer of RIA consolidation. The question for the investment management industry remains: is consolidation the answer?

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights