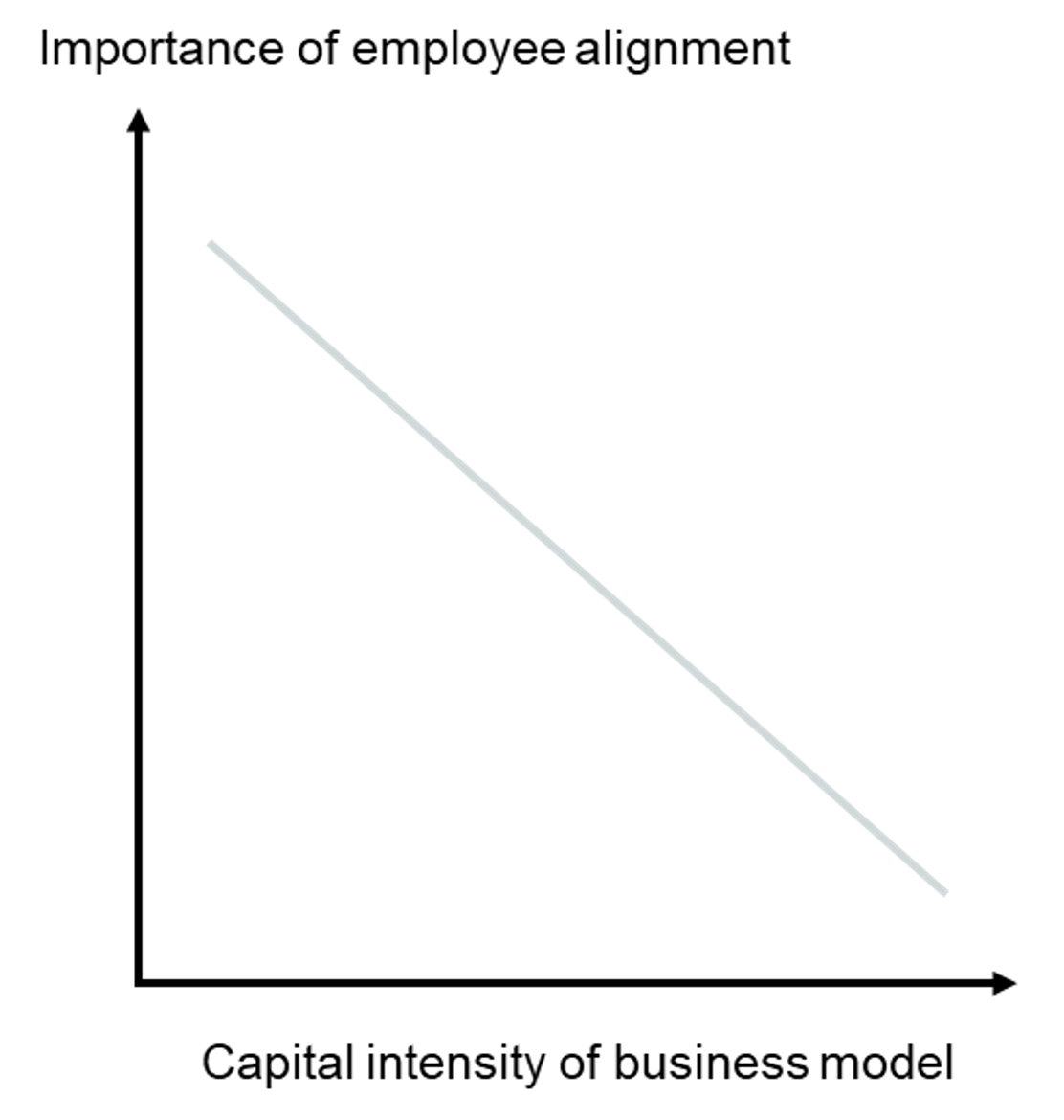

Employee alignment is important for most companies, but in asset and wealth management, it’s essential. A useful framework for thinking about the importance of employee alignment is to think of it as a function of the capital intensity of a business model:

For a capital-intensive business, capital (fixed assets) is the primary input to generate the goods or services that the company produces. Labor is relatively less important. In such a business, you’d, of course, like to have employee alignment, but the significance of that employee alignment is relatively less because employee labor is a small part of the total input to produce the company’s output. For wealth management, the “capital” (in the traditional sense) required to generate the services the company provides is minimal: it’s the chair you’re sitting in, the monitor you’re looking at, and not a whole lot else. Wealth management is a people business, and the efforts of those individuals are the real “capital” of investment management. Given the importance of labor as an input to wealth management services, creating alignment between employees and shareholders is critical for the growth and success of the enterprise. The degree of outside ownership also plays a role in employee alignment. Many RIAs are majority-owned by employees, and when outside ownership is low, having appropriate mechanisms in place to align interests is relatively less important because employees and shareholders are the same people. In such situations, distributions often serve as the employee incentive in place of W-2 compensation.

The degree of outside ownership also plays a role in employee alignment.

While wealth management is traditionally an owner-operator business, it’s not uncommon for firms to have a significant degree of outside ownership. This can happen for a variety of reasons: a major shareholder retires and retains their ownership stake, a partner dies and their ownership passes to their spouse or other beneficiaries, the firm brings on a minority investor to provide liquidity to existing shareholders or growth capital, and the list goes on. As the industry matures and outside capital becomes increasingly prevalent, more and more firms find themselves in situations such as these.

The greater the ownership stake held by non-employee shareholders, the more potential there is for employee and shareholder interests to diverge. For firms with a high degree of outside ownership, the importance of establishing mechanisms to align the interests of employees with shareholders is amplified.

How Do You Create Employee Alignment?

As you think about employee alignment, the first step is identifying the interests of the firm’s stakeholders at present. Shareholders may be focused primarily on near-term distributions, but they often take a longer-term perspective focused on growing distributions and the value of the business over time. For employees, their interest is typically maximizing W-2 compensation.

From there, the question becomes: how do you create a compensation model that aligns employee objectives (maximizing compensation) with shareholder goals (growing distributions and the value of the business over time)? In the short run, this is admittedly difficult. At the end of the year, splitting up the results of the firm’s operations (pre-bonus profitability) between employees and shareholders is a zero-sum game. As one side gets more, the other gets less.

However, when a longer-term perspective is adopted, compensation spend can be viewed not as a drag on shareholder returns but as a lever for growth and alignment of interests. As discussed in last week’s blog, it can be a useful exercise to analyze compensation spend through the lens of capital budgeting. Under this framework, compensation spend represents an investment in people. Like any investment, an investment in people has risk—but when done properly, there’s an expected return that justifies that risk.

Compensation can be used to align employee and shareholder interests, but compensation spending in and of itself is not equivalent to alignment. It’s worth taking a critical look at your firm’s compensation model because when it comes to alignment, how you pay people is as important as what you pay them. A compensation model that effectively aligns employee and shareholder interests will create incentives for employees to grow and protect the same metrics that shareholders care about and will incentivize actions that translate to achieving shareholder objectives of growing the value of the business over time.

Compensation can be used to align employee and shareholder interests, but compensation spending in and of itself is not equivalent to alignment.

A note on incentive compensation: it only works to the extent that employees understand the process and levers through which incentive compensation is determined. Thus, it’s important to have a defined process around an incentive compensation program that can be articulated to employees. Otherwise, the incentives offered to employees may be viewed as arbitrary. When it comes to incentives, perception is reality. If employees don’t understand how those incentives are determined, you’re not maximizing your return on incentive compensation spending.

A properly structured incentive compensation model can be a powerful tool for aligning interests and investing in the future growth of the business. Of course, there’s no guarantee that incentive compensation will translate to higher growth. Like any investment, an investment in people has risks.

What we can say with little equivocation is this: people respond to incentives. That’s one of the most robustly proven results in the world of psychology and an underpinning assumption in economics. Investing in employee alignment through incentives is the first step to action. Whether that action translates to the desired results is where the risk is. Is that investment worth the risk? Without the right investment in employee alignment, it’s incredibly difficult to grow and sustain an investment management firm. You might not always get what you pay for, but you’ll never get what you don’t pay for.