Formula Pricing Gone Wrong

What Happens If Your Buy-Sell Agreement Prices Your Firm Too High or Too Low?

Hard to imagine today, but just one year ago, some of the largest prices paid for new cars relative to MSRP were for an EV. The Porsche Taycan, a six-figure ride in any configuration, was commonly selling for 20-25% above sticker. What a difference a year makes. Today, EVs are shunned by many (certainly the press), and Porsche is rushing out a new version of the Taycan for 2025 to address flagging sales. For those who paid premium prices to Zuffenhausen a year ago, the depreciation they’ll experience if they try to trade that year-old Taycan today would be breathtaking. Life’s a gas!

Pricing Matters

The backbone of our business at Mercer Capital is valuation, so we have a self-interested bias against formula prices in buy-sell agreements. An independent valuation is, by far, the best way to manage the settlement of transactions between shareholders. Doing so annually has the added benefit of managing everyone’s expectations.

Simple is not always better

I’ll concede that annual valuations can be excessive for smaller firms with a few shareholders and transactions that seldom occur. Formula pricing offers a degree of certainty and grounds expectations in what is usually a pretty simple equation. Simple is not always better, however.

More often than not, the formula prices we encounter do more harm than good. The simplicity of formula pricing equations means they don’t consider important factors like debt, non-recurring items, loss of key staff or large customers, market conditions, or offers to purchase. Formulas can ground expectations but may set expectations unrealistically low or high, provide a false sense of security, and encourage partner behaviors that do not support the business model.

The Object of Transaction Pricing

In part, buy-sell agreements offer a mechanism to settle transactions between shareholders when some event forces a transaction. Often the event is many years, if not decades, after the signing of the agreement. Nobody expects to be thrown out of their firm, get divorced, or die — even though we know the former two happen often and, in the case of the latter, happens to everyone. Even retirement is hard to foresee when a firm is in its nascency and crafting a shareholder agreement to handle issues that seem so far off that even the inevitable is irrelevant.

Signers to a buy-sell rarely foresee the consequences

As such, the signers to a buy-sell rarely foresee the consequences of what they’re signing. Many of these consequences involve valuation.

If you ask them, most people say they want the pricing mechanism in their shareholder agreement to treat everyone fairly. “Fair” is the first word in Fair Market Value, a standard of value established by the Treasury Department in Revenue Ruling 59-60 and reiterated and expounded upon in professional literature throughout the valuation community.

Fair Market Value, generally, is a standard of pricing that considers the usual motivations of typical buyers and sellers, described as hypothetical parties, to distinguish them from the very specific and particular persons involved in a subject matter. The parties to a fair market value transaction are assumed to be funded, informed, and reasonable. Fair market value further assumes an orderly (not forced) transaction, and settlement is on a cash equivalent basis.

Most people want something akin to fair market value pricing in a buy-sell agreement, but formulas usually only achieve this by coincidence. Most formulas will either price an interest too high or too low. This creates “winners” and “losers,” depending on who gets the better side of the transaction.

When the Formula Price Is Too High

We often see formula pricing in buy-sell agreements set at what could be called optimistic levels. I suppose this is because these agreements are usually written when firms are first established, too new to evaluate the stabilized economics of the business model when compensation patterns are observable, fee schedules are settled, and margins become regular.

Formula pricing commonly relies on rules of thumb

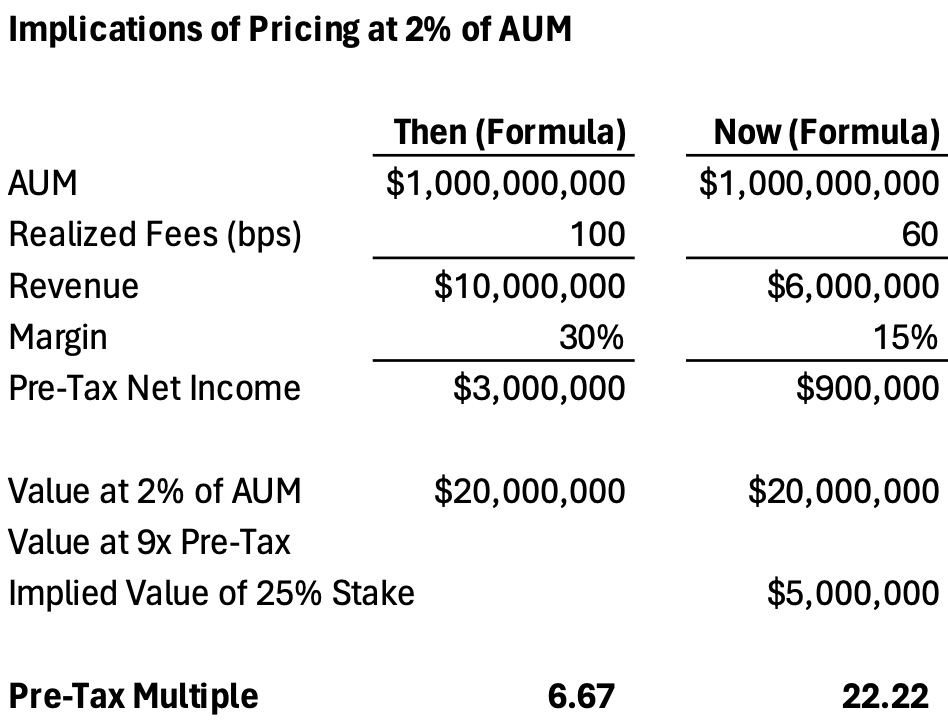

Formula pricing commonly relies on rules of thumb that don’t represent the particular economic characteristics of a given RIA’s business model. An example of this would be the old myth that investment management firms were worth 2% of AUM.

The 2% rule dates back to the days before wealth management and asset management were well delineated, and money managers commonly earned a realized effective rate of 100 basis points on assets under management. At those fees, a billion-dollar shop could produce pre-tax margins between 25% and 35%. At those margins, 2% of AUM implied a value of 6x to 8x pre-tax net income. At the time, that pricing was reasonable. RIAs were not considered an established money management platform (broker-dealers were still the dominant force), and consolidation activity was minimal. Industry insiders recognized that RIA clients were stickier than those of most professional services firms, so 6x to 8x pre-tax net income was a premium to a more typical 4x-5x for other owner-operator professions.

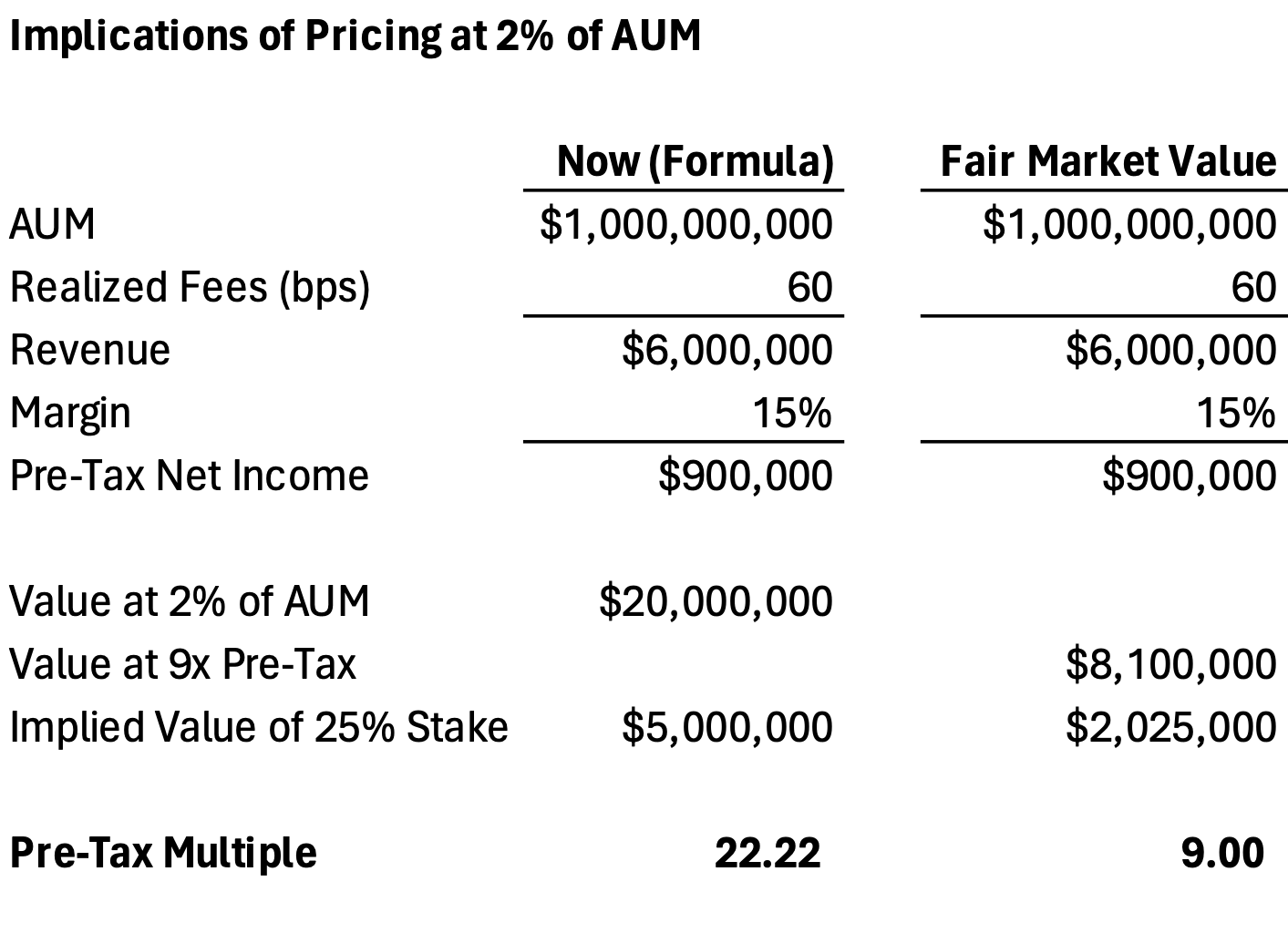

Today, of course, consolidation activity is rampant, and multiples are generally higher. But fees have taken a hit, and not every firm earns a “normal” margin. If realized fees are 60 basis points and margins are 15%, a formula that values the RIA at 2% of AUM looks pretty expensive.

There is a very human tendency to get too comfortable with large numbers. Owners like big valuations, even when they aren’t real. And until an event occurs that requires a transaction, people rarely question a robust, if unrealistic, valuation. It’s a game of mental gamma, where everyone hopes imaginary pricing pulls on value like a large block of out-of-the-money call options. It feels good but doesn’t get tested until a triggering event invokes the buy-sell agreement.

Then something happens. If a 25% partner in this “Now” RIA passes away unexpectedly, and the buy-sell agreement specifies purchase at 2% of AUM, the transaction price is $5 million. We’re going to posit, for purposes of this post, that the actual fair market value of this interest is 8x-10x pre-tax, the midpoint of which is 9x. At 9x pre-tax, the 25% stake has an implied value of about $2 million. If the RIA is required to purchase the interest pursuant to the formula, they will be paying over 60% of the value of the firm for a 25% stake. The estate “wins,” and everyone else loses.

What are the implications of an internal transaction at 22x pre-tax? Let’s assume the buy-sell agreement states the RIA can finance the purchase of the decedent’s interest at SOFR plus 200 basis points (about 7.3% today) over ten years. The annual payment would be nearly $725 thousand, or 80% of pre-tax (a proxy for distributable cash flow). For a decade, 80% of distributions will be claimed by a 25% ownership interest.

80% of distributions will be claimed by a 25% ownership interest

We’ve seen this happen, but there are reasons the formula pricing might not hold. Usually, a buy-sell gives the other partners and/or the firm the option to purchase at the formula price but doesn’t require it. In this case, the option is entirely out of the money. In that case, the firm might decide to punt on the option and pay the estate their pro rata portion of distributions ($225K per year, or about $500K less than financing at the formula price). The estate is left as an outside minority owner in a closely held business. If the estate isn’t satisfied with this, the executor will have to negotiate — from a very weak position — with the other partners. In effect, this nullifies the buy-sell agreement.

When the Formula Price Is Too Low

Buy-sell formulas that undervalue interests are no better than those that overvalue interests. There is no “conservative” or “aggressive” in valuation, only reasonable and unreasonable. If, in the scenario listed above, the formula price specified that the firm was to be valued based on book value, the outcome would be no more favorable.

RIAs usually don’t have much balance sheet value. Our valuations in the space rarely employ an asset approach. We consider whether the balance sheet has a normal level of working capital to finance ongoing operations or if it has a material amount of non-operating assets. Beyond that, the balance sheet is rarely more than some cash, leasehold improvements, and short-term payables. Book value for a firm like the one discussed above might be no more than $250K.

At book value, that formula would price the decedent’s interest at $62,500 — unreasonable for a stake that was earning over three times that much in annual distributions. The transaction would be highly accretive to the remaining partners, who would share in the distribution stream they got for next to nothing. But the specter of what would happen to their beneficiaries in the event of their deaths would dampen any sense of having won.

If this buy-sell formula also applies in the event of retirement or withdrawal from the firm, who would ever leave? It would be very difficult to execute ownership succession for partners who are giving up their distributions in exchange for so little compensation. Of course, without succession, the firm eventually wears out — a circumstance in which book value might be a reasonable measure.

What’s Your Aspiration?

Ask yourself whether or not you think the pricing of a forced transaction should create “winners” and “losers.” There are legitimate reasons for wanting a somewhat below-market price for transactions because it benefits the ongoing firm and continuing partners. Above-market pricing just creates a race for the exit. But if your formula price is too high and transaction execution is optional, an informed buyer will pass, and you’ll be negotiating as if there were no agreement. Hardly a good solution.

If this has prompted you to think about your formula pricing and you’d like to talk specifics to us in confidence, reach out. We work with hundreds of investment management firms like yours to defuse time bombs and create reasonable resolutions. Don’t let your ownership issues disrupt your operations.

RIA Valuation Insights

RIA Valuation Insights